Полная версия:

For the Record

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © David Cameron 2019

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

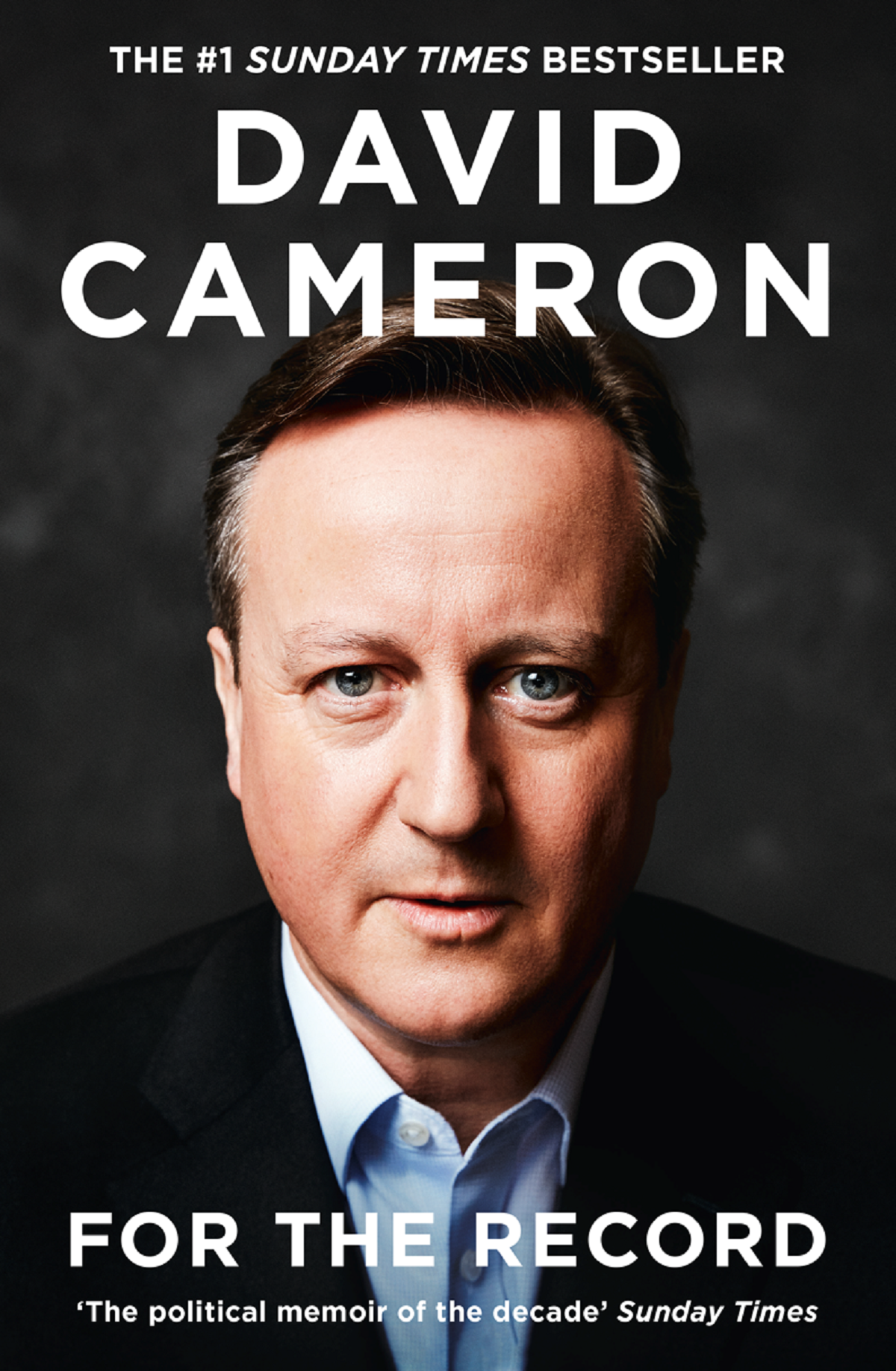

Cover photograph © Chris Floyd

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008239282

Ebook Edition: September 2019 ISBN: 9780008239305

Version: 2019-10-02

Dedication

For Samantha

Contents

1 Cover

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Contents

6 List of Illustrations

7 Foreword

8 1 Five Days in May

9 2 A Berkshire Boy

10 3 Eton, Oxford … and the Soviet Union

11 4 Getting Started

12 5 Samantha

13 6 Into Parliament

14 7 Our Darling Ivan

15 8 Men or Mice?

16 9 Hoodies and Huskies

17 10 Cliff Edge, Collapse and Scandal

18 11 Going to the Polls

19 12 Cabinet Making

20 13 Special Relationships

21 14 Afghanistan and the Armed Forces

22 15 Budgets and Banks

23 16 Nos 10 and 11 – Neighbours, Friends and Families

24 17 Progressive Conservatism in Practice

25 18 Success and Failure

26 19 Party and Parliament

27 20 Leveson

28 21 Libya and the Arab Spring

29 22 Referendum and Riots

30 23 Better Together

31 24 Treaties and Treadmills

32 25 Omnishambles

33 26 Coalition and Other Blues

34 27 Wedding Rings, Olympic Rings

35 28 Resignations and Reshuffles

36 29 Bloomberg

37 30 The Gravest Threat

38 31 Sticking to ‘Plan A’

39 32 Love is Love

40 33 A Slow-Moving Tragedy

41 34 Leading for the Long Term

42 35 A Distinctive Foreign Policy

43 36 The Long Road to 2015

44 37 Junckernaut

45 38 A ‘Small Island’ in a Small World

46 39 Back to Iraq

47 40 Scotland Remains

48 41 The Sweetest Victory

49 42 A Conservative Future?

50 43 Rolling Back the Islamic State

51 44 Trouble Ahead

52 45 Renegotiation

53 46 Referendum

54 47 The End

55 Picture Section

56 Index

57 About the Author

58 About the Publisher

LandmarksCoverFrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiiiivvixxxixiiixivxvxvixviixviiixix123456789101112131415161718192021222324252627282930313233343536373839404142434445464748495051525354555657585960616263646566676869707172737475767778798081828384858687888990919293949596979899100101102103104105106107108109110111112113114115116117118119120121122123124125126127128129130131132133134135136137138139140141142143144145146147148149150151152153154155156157158159160161162163164165166167168169170171172173174175176177178179180181182183184185186187188189190191192193194195196197198199200201202203204205206207208209210211212213214215216217218219220221222223224225226227228229230231232233234235236237238239240241242243244245246247248249250251252253254255256257258259260261262263264265266267268269270271272273274275276277278279280281282283284285286287288289290291292293294295296297298299300301302303304305306307308309310311312313314315316317318319320321322323324325326327328329330331332333334335336337338339340341342343344345346347348349350351352353354355356357358359360361362363364365366367368369370371372373374375376377378379380381382383384385386387388389390391392393394395396397398399400401402403404405406407408409410411412413414415416417418419420421422423424425426427428429430431432433434435436437438439440441442443444445446447448449450451452453454455456457458459460461462463464465466467468469470471472473474475476477478479480481482483484485486487488489490491492493494495496497498499500501502503504505506507508509510511512513514515516517518519520521522523524525526527528529530531532533534535536537538539540541542543544545546547548549550551552553554555556557558559560561562563564565566567568569570571572573574575576577578579580581582583584585586587588589590591592593594595596597598599600601602603604605606607608609610611612613614615616617618619620621622623624625626627628629630631632633634635636637638639640641642643644645646647648649650651652653654655656657658659660661662663664665666667668669670671672673674675676677678679680681682683684685686687688689690691692693694695696697698699700701702703705706707708709710711712713714715716717718719720721722723724725726727728729730731732

List of Illustrations

With John Major (Neil Libbert)

Norman Lamont gives a press conference on Black Wednesday (Bott/Mirrorpix/Getty Images)

Campaign in Witney for leader of the Conservative Party (Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images)

With Samantha, Ivan, Elwen, Nancy (Tom Stoddart/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Conservative party conference in Blackpool (Jeff Overs/BBC News & Current Affairs/Getty Images)

Press conference after the second ballot for the 2005 leadership contest (Bruno Vincent/Getty Images)

Leadership election win (Bruno Vincent/Getty Images)

Sudan visit (Andrew Parsons/PA Images)

With George Osborne (Andrew Parsons)

Dog sled in Svalbard, Norway (Andrew Parsons/PA Images)

Speaking on Big Society (Andrew Parsons)

In Balsall Heath with Abdullah Rehman (James Fletcher)

With Boris Johnson (Andrew Parsons)

Statement at St Stephen’s Club on the possibility of a hung Parliament (Lefteris Pitarakis/WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Watching Gordon Brown’s resignation (Andrew Parsons)

Arrival in Downing Street with George Osborne and William Hague (Andrew Parsons)

First press conference with Nick Clegg after the coalition agreement (Andrew Parsons)

The door of Number 10 with Margaret Thatcher (Andrew Parsons)

Afghanistan visit (Leon Neal/AFP/Getty Images)

Hamid Karzai’s visit to Chequers (Andrew Parsons)

Bloody Sunday inquiry statement (Peter Muhly/AFP/Getty Images)

Signing the independence referendum agreement with Alex Salmond (Gordon Terris/Pool/Getty Images)

Speaking in Benghazi (Philippe Wojazer/AFP/Getty Images)

Meeting local residents in Benghazi (Stefan Rousseau/AFP/Getty Images)

Queen Elizabeth II attends the government’s weekly cabinet meeting (Jeremy Selwyn/WPA Pool/Getty Images)

The Olympic torch arrives in Downing Street (Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images)

Florence at the Alternative Vote referendum campaign (Andrew Parsons)

Barack Obama meeting Larry the cat (White House/Alamy)

Meeting with Barack Obama at the Camp David G8 (Obama White House)

G8 and EU leaders at the Britain G8 Summit (Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images)

With Vladimir Putin at the Olympics (Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images)

With Angela Merkel at Chequers (Justin Tallis/Pool/Getty Images)

The G7 participants in Bavaria (A.v.Stocki/ullstein bild/Getty Images)

Working on the contents of the red box (Tom Stoddart/Getty Images)

Holding the letter left by Liam Byrne reading ‘I’m afraid there is no money’ (Andrew Parsons)

Campaigning for the 2015 election (Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

Writing the losing speech ahead of the 2015 general election (Andrew Parsons)

Visiting the Sikh festival of Vaisakhi in Gravesend (WENN Rights Ltd/Alamy)

Celebrating the winning count during the 2015 general election (Andrew Parsons)

Returning to Downing Street (Arron Hoare/MOD, Crown Copyright © 2015)

With Angela Merkel, Fredrik Reinfeldt and Mark Rutte in a boat in Harpsund (Jonathan Nackstrand/AFP/Getty Images)

With Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borisov at the border iron fence (NurPhoto/Getty Images)

At Wembley Stadium with India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi (Justin Tallis/WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Drinking a beer with China’s president Xi Jinping (Kirsty Wigglesworth/WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Meeting Donald Tusk and Jean-Claude Juncker (Yves Herman/AFP/Getty Images)

Inspecting the renegotiation documents with Tom Scholar and Ivan Rogers (Liz Sugg)

Addressing students and pro-EU ‘Vote Remain’ supporters (Christopher Furlong/Getty Images)

Watching the EU referendum results come in (Ramsay Jones)

Nancy, Elwen and Florence Cameron writing a letter for the incoming prime minister (Andrew Parsons)

Preparation for the final appearance at Prime Minister’s Questions (Andrew Parsons)

The last official visit as prime minister (Chris J Ratcliffe/WPA Pool/Getty Images)

With family before leaving Downing Street (Andrew Parsons)

Visit to Alzheimer’s UK (Edward Starr)

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. Where not explicitly referenced, the pictures are sourced from the author’s personal archive. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions in the above list and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future editions of this book.

Foreword

It is three years since the referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union. Not a day has passed that I haven’t thought about my decision to hold that vote, and the consequences of doing so.

Yet during that time I have barely spoken publicly about it, or about any issues around my premiership. The reason is that I wanted to let my successor get on with the job. It is hard enough being prime minister – let alone one who has the momentous task of delivering Brexit – without your immediate predecessor giving a running commentary.

That silence has inevitably let certain narratives develop, for example about my motivations for holding the referendum and about my departure from Downing Street. There has been analysis of aspects of my premiership – from the campaign in Libya to the schemes that have helped so many people to buy their own home – with which I have disagreed deeply.

But my discomfort at not being able to respond to these things is nothing compared to the pain I have felt at seeing our politics paralysed and our people divided. It has been a bruising time for Britain, and I feel that keenly.

Yet just as I believe it is right for prime ministers to be allowed to get on with their job without interference, I also believe it’s right for former prime ministers to set out what they did and why – and to correct the record where they think it is wrong.

Fortunately, I kept a record during my time in the job. Every month or so, my friend and adviser, the journalist Danny Finkelstein, would come to the flat above 11 Downing Street where I lived with my wife Samantha and our three young children. Danny and I would sit on the sofas in the bright sitting room that overlooked St James’s Park, as he gently quizzed me about recent events.

Those recordings have helped me write this memoir, just as scribbles in a notebook or recordings on a dictaphone have assisted others. I sometimes quote directly from the recordings because they provide such an insight into how I felt at the time. Hearing them back – and writing this book – has helped me to understand how I feel about it all now.

A friend once asked Margaret Thatcher what, if she had her time again, she would do differently. There was a thoughtful pause, then she answered: ‘I think I did pretty well the first time.’ I don’t feel quite the same. When I look back at my career in politics, I do have regrets. Lots. Not every choice we made during our economic programme was correct. There were many things that could have been handled better, like the health reforms. What happened after we prevented Gaddafi slaughtering his people in Benghazi was far from the outcome I’d have liked. The first parliamentary vote on intervention in Syria was a disaster.

And around the EU referendum I have many regrets. From the timing of the vote to the expectations I allowed to build about the renegotiation, there are many things I would do differently. I am very frank about all of that in the pages that follow. I did not fully anticipate the strength of feeling that would be unleashed both during the referendum and afterwards, and I am truly sorry to have seen the country I love so much suffer uncertainty and division in the years sincethen.

But on the central question of whether it was right to renegotiate Britain’s relationship with the EU and give people the chance to have their say on it, my view remains that this was the right approach to take. I believe that, particularly with the Eurozone crisis, the organisation was changing before our very eyes, and our already precarious place in it was becoming harder to sustain. Renegotiating our position was my attempt to address that, and putting the outcome to a public vote was not just fair and not just overdue, but necessary and, I believe, ultimately inevitable. I know others may take a different view, but I couldn’t see a future where Britain didn’t hold a referendum. So many treaties had been agreed, so many powers transferred and so many promises about public votes made and then not fulfilled. With all that was happening in the EU, this could not be sustained.

Of course there are many who welcomed the referendum – and that was reflected in the overwhelming vote for it in Parliament and in the high public turnout when the time came. Far from being a flash in the pan, the referendum was announced more than a year before the 2014 European elections and more than two years before the general election. It was set out clearly in a manifesto that delivered an overall majority in the House of Commons.

But I know there are those who will never forgive me for holding it, or for failing to deliver the outcome – Britain staying in a reformed EU – that I sought. I deeply regret the outcome and accept that my approach failed. The decisions I took contributed to that failure. I failed. But, in my defence, I would make the case, as I think all prime ministers have, that especially when you are in the top job, not doing something, or putting something off, is also a decision.

And that is the thing that stands out for me when I look back over this time: decision-making. A prime minister these days is constantly in contact with their office by email, text and messenger services and is therefore making decisions, large and small, almost by the minute. They also, as I did over the EU referendum, consider the biggest decisions over months, even years. It’s the most difficult, most stressful, yet most rewarding part of the job. In many ways, it is the job (and I almost called this book Decisions for that very reason).

Indeed, so many of Britain’s problems we found when we came to power in 2010 were a result of decisions that had been put off. The government had spent and spent while the deficit and debt were left to grow and grow. Low pay and high taxes had been plugged by an ever increasing benefits system. Educational standards were sliding, but masked by increasingly generous grades. More and more people were going to university, but the system was becoming unsustainable. Big calls on infrastructure were avoided while new superpowers raced ahead. Immigration went up and up but without the control, integration and public consent that is needed to sustain such rapid changes to our society. Businesses were hamstrung by regulation and economic growth was excessively concentrated in the south-east. And yes, as I’ve said, Britain’s unstable position in a changing EU was the biggest can kicked down the longest road.

In order to confront these issues we had to do several bold things. We had to modernise the party and make it electable once again – not with a modest change to our image but a full-blown overhaul of who we were, the issues we addressed, how we conducted ourselves and what we had to say to people in twenty-first-century Britain.

Then we had to do something just as bold: form the first coalition government since the Second World War (unpalatable for many in our party) and make it endure (impossible, according to many commentators). We then had to fix the country’s finances after the worst crash in living memory. At the same time, we were bringing troops home from Afghanistan, while facing down security threats at home and around the globe.

None of these things was inevitable. They happened because we made them happen. Indeed, many things happened – as this book will show – simply because I got a bee in my bonnet about an issue and got the bit between my teeth (and like most modern politicians, mixed my metaphors along the way).

The youth volunteering programme National Citizen Service is something I am often stopped about in the street – and it was an idea I dreamt up many years ago. Technology is changing our world for the better in healthcare, finance, development, transport, the environment and much else besides, and – partly because of the support we gave in government – the UK is in the vanguard of all things ‘tech’. The UK is also leading the world in dementia research and care – and putting it on the global agenda all started when, as an MP, I realised the extent and implications of diseases like Alzheimer’s. Britain is one of the few countries to meet and keep its promise to the poorest in the world by spending 0.7 per cent of its national income on international aid and development. It’s something I’ve always felt passionately about and wouldn’t relent on in government. In fact, these four things – volunteering, tech, dementia and aid – have been my focus outside politics over the last few years.

For all the dissatisfaction with the futility of politics and the failures of politicians, the progress we made on them in government proves you can make a difference.

We were practising politics in the early twenty-first century, at a time when that dissatisfaction – with politics, with an entire global system – was on the rise. 9/11 and 7/7 led to a sense of physical and cultural insecurity. The 2008 financial crash led to economic insecurity. People looked to those in authority for answers. But all they saw were people in power failing – from MPs fiddling expenses to journalists hacking phones and bankers gambling on our global economy.

Much of what we did in government was focused on combatting economic insecurity. We helped create a record number of jobs, cut taxes for the lowest paid and substantially increased the minimum wage.To address security concerns we established the National Security Council, backed our intelligence and security services and sharpened the focus on combatting all forms of Islamist extremism. Not just the appalling violence, but the poisonous narratives of exclusion and difference on which it feeds.

However, it was in the field of dealing with the sense of cultural insecurity that we failed most seriously. I support a world with global institutions and rules, and fundamentally believe that – on the whole – this is in Britain’s interests. But an impression has grown that the interests of our country, our nation state, are on occasion secondary to some wider global or institutional goal. Most of the time this is nonsense. Occasionally – and the European Court of Human Rights is the most prolific offender here – it is correct. We should have done more to override this when true, and challenge it when not.

Most importantly, we failed to deliver effective control over levels of immigration in to our country and to convey a sense that the system we were putting in place was in the national interest.

Those who share my enthusiasm for free markets, open economies and diverse societies have got to recognise that none of these things will endure unless we deal with the insecurities – and demonstrate that doing so is absolutely vital to making our country more prosperous. The debate now seems to be ‘pro globalisation’ versus ‘anti globalisation’. My point is that we have to listen to the genuine arguments of those who are ‘anti’ if we are to preserve what I believe we all ought to be ‘pro’.

Readers might wonder why I have dedicated so much space to the early years of opposition and modernisation of the Conservative Party. It all seems rather distant, even irrelevant to today’s troubles – hoodies, huskies, the Big Society are literally ‘so 2008’. I disagree. It may be tempting to respond to these desperate times with desperate measures – to become louder and more extreme in our answers. But I believe the opposite is required. I look back at the approach we were taking in opposition, during the early years of this young century – moderate, rational, reasonable politics – and I realise those things are more important than ever.

In these difficult, disputatious times, as this young century reaches its twenties, I passionately believe the centre can hold. The centre is still the right place to be – a bold, radical, exciting place to be (which is why another working title for this book was Right at the Centre).

Winning the 2015 election after five years of coalition, difficult economic decisions and bold measures, like legislating for gay marriage, was proof that commanding the rational, centre ground can deliver good government and good politics too. It is the approach – in my view – that should be applied to Brexit. The most sensible, most rational (and the safest) approach would be to seek a very close partnership with the organisation that will remain our biggest source and destination for trade, as well as a vital partner for peace, security and development. Our aim in delivering the outcome of the referendum should be, as I put it in this book, to become contented neighbours of the EU rather than reluctant tenants.

I have tried throughout the book to mention as many people as I can who worked with me over the years, from those who mentored me when I was a young researcher starting out in politics, to my own special advisers when I was PM. I am sorry to anyone I’ve missed. I am so proud of you all – not only of what we achieved together but what so many have gone on to do, in finding centre-right answers to the biggest problems we face, from climate change to poverty, modern slavery, an ageing society and more.