Полная версия:

Washington and Caesar

Washington and Caesar

Christian Cameron

To my father.

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Author’s Note

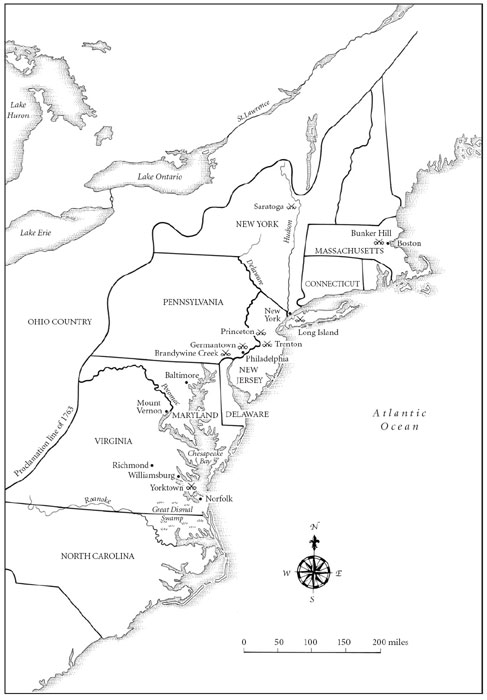

Map

I Wanderers in the Wilderness

1

2

3

4

5

II Taking off Terror

1

2

3

4

5

III War

1

2

3

4

5

IV Liberty or Death

1

2

3

4

V Care and Labour

1

VI Peace

1

Historical Note

Select Bibliography

Acknowledgments

Washington and Caesar

Copyright

About the Publisher

Author’s Note

There can be few topics as difficult to confront for an American author as the mythology attached to George Washington. If there is a topic as difficult, it is surely those issues surrounding blacks and slavery in Colonial America. The combination of the two may provide an obstacle so far beyond my merits as an author as to be insurmountable.

Rather than seeking to excuse any failures, however, I would prefer to lull the reader with a few assurances. The events of this book are firmly rooted in history; for indeed, Washington’s life was so well chronicled (by his own hand, among many others) that it could not be otherwise. I have tried to portray the life of black slaves equally well, based on the handful of contemporary accounts of survivors of that pernicious system. And the events of the American Revolution occurred very much as chronicled here. The British did not inevitably fight in long straight lines, the Americans were not all “Patriots”, and the results of the struggle gave birth not just to the United States, but to Canada as well.

To those hard truths let me add one other. All society of the day was hierarchical; all men, black or white, had superiors and inferiors, and expected certain behavior of each, and all too many were content that it be so. They were different. I have tried to portray this throughout, but I shall leave you to judge the result.

Map

I Wanderers in the Wilderness

Slaves, obey in all things your masters according to the flesh, not with eyeservice, as menpleasers, but in singleness of heart, fearing God. And whatsoever you do, do it heartily, as to the Lord, and not unto men; knowing that of the Lord ye shall receive the reward of the inheritance, for ye serve the Lord Jesus Christ. But he that doeth wrong shall receive for the wrong which he hath done, and there is no respect of persons.

Masters, give unto your slaves that which is just and equal; knowing that you also have a Master in heaven.

COLOSSIANS 3:22-25

1

Great Kanawaha, Ohio country, October 26, 1770

The tall man’s horse started at the distant shot, and he curbed it firmly, his attention on the woods around him. The sun, far overhead, pierced the canopy of trees with beams that played in shifting patterns on the autumn mold of the forest floor. For a moment his thoughts were in another forest, and the sound of other shots rang in his ears. His horse’s uneasiness communicated itself to the rest of the horses in the party.

“Hunter?” The other white man stood in his stirrups, as if a few inches of height would improve his view of the woods.

The tall man’s attention returned to the horses.

“Pompey, if you can’t control that animal I’ll have you walk.”

The black man so addressed wheeled his horse in a tight circle, murmuring all the while. His horse stopped fidgeting. The whole party grew still.

The second shot was farther away, the low thump of a musket.

“Crogan said we’d find a hunting camp.” The tall man ran his eyes over the rest of his party and touched his heels to his horse’s flanks, moving off at a trot. He already seemed focused on a distant goal, but the other men, black and white, cast their eyes nervously on the woods around them as they moved off on the narrow track. He slowed his horse to a comfortable walk and flowed in next to the other white man.

“No point in hurry, Doctor. We’ll need Nicholson to talk to them.”

The doctor seemed oppressed by the shots, but if the tall man noticed it, he gave it no heed.

“You were speaking of the price of tobacco, Colonel.”

“So I was, Doctor. Probably dwelling on it more than is healthy. But if the price continues to fall, we’ll all have to find another crop or see our sons debtors.”

“You’ve planted wheat, sir?” Dr. Craik was always a little diffident with Washington, who was not just his friend but frequently his patron.

“Indeed. I don’t grow tobacco except to cover expenses, but my tenants are old-fashioned men and need to see a thing done many times before they’ll consider it. I am confident that the soil will support it. And the price is better, whether I sell it in the Indies or grind it myself.”

“It could make a difference, sure enough.”

“I doubt it. The Virginia gentry are too used to easy money from tobacco to settle for a hard living on wheat.”

“Perhaps the price will rise in time, sir.”

“Oh, it may. But there are bills due now. I’ve had two bills refused in London, on very worthy men, at that. Gentlemen. They write bills to cover the cost of my smith and the like, you know. And those bills were refused. Very alarming.”

“Ho’se behin’ us, suh.”

“Thank you, Pompey. Good ears, as usual. That would be Nicholson,” he said. “And I sold Tom. Did I tell you that?”

The two black men looked at each other, just for a moment, but neither white man remarked it.

“You said he was a problem.”

“That he was. Ironical, if you can believe it. And he tried to run. I wouldn’t have it, so I sold him in the Indies. I asked Captain Gibson to get me another, good with animals. We’ll see what he brings.” The tall man stopped his horse and turned, one hand on its rump. A white man on a small horse was trotting up the trail, a rifle across his arm and the cape of his greatcoat turned up around his face against the chill.

“Are you sober, Nicholson?”

“Aye, Colonel. Sober as a judge.”

“Hear the shots?”

“Aye. That’d be the Shawnee that Crogan was on about.”

“Let’s go find them, then.”

Nicholson glared a moment, his narrow eyes stabbing from under heavy brows. Then he shook his head, touched his mount with his heels, and passed to the front.

Whatever his state of sobriety, Nicholson found the Shawnee camp so quickly that the conversation never seemed to rise again, beyond muttered comments about the beauty of the country. The party moved on at a trot until the hard-packed trail opened into a small clearing with several brush wigwams around its periphery. There was a strong smell of butchered meat and rot, overlaid with wood smoke. Two native women were scraping a hide. An old man sat smoking. None showed any sign of alarm when the party rode in. The tall man dismounted and threw his reins to one of his blacks.

“Ask them if we can stay the night.” He inclined his head civilly to the two women, who laughed and smiled.

Nicholson didn’t dismount. He nudged his horse forward, raised his right hand toward the old man, and spoke a long, musical sentence. The man drew on his pipe, blew a smoke ring, and nodded. Another shot sounded, quite close. The old man batted at a fly with a horsetail whisk and waved at the tall man, then spoke for a moment.

Nicholson turned to the tall man. “Says he knows you, Colonel Washington. Says you’re welcome here.”

“Excellent. Dr. Craik, this is our inn for the night. Please dismount. I’ll have Pompey and Jacka set up a tent.”

Pompey made coffee at one of the small native fires while Dr. Craik admired the skill of the women in cleaning the deer hides, a thoroughness his assistant back in Williamsburg would have done well to emulate.

“They learn as girls,” said Washington in a level tone.

“Use makes master, I suppose. Handsome wenches, too.”

“Oh, as to that…” He looked off into the middle distance and took a cup of coffee from Pompey without glancing at the man. “Beautiful country. Look at this clearing. Trees that big come out of the best soil.”

“And the savages have little idea what to do with it.”

“They grow corn well enough. Better than some of my tenants, if the truth were known.”

“I had no idea.”

“Not so savage, when it comes to farming. Of course, the women do it. Men mostly hunt and fight.” He sipped his coffee appreciatively. The old man was still smoking, looking at him from time to time but otherwise off in his own thoughts. Washington couldn’t place him, although he had a good memory for men he had known during the wars.

Between one thought and the next, the clearing began to fill with native men, all younger and most carrying guns. Others carried deer carcasses on poles or dragged them by the legs. Nicholson, his back against a tree and a bottle in his hand, called a greeting, and two men walked over to him. One took a drink from his bottle when it was offered, and they had a short exchange. The old man merely waved the flywhisk several times and the deer began to be sorted out.

“That fellow is a black!” Dr. Craik was pointing at a tall man in red wool leggings.

“Yes, Doctor. So he is. Probably started as a captive.” Washington nodded civilly at the warrior so indicated, who inclined his head a dignified fraction in return.

“We didn’t see blacks among the Shawnee during the wars.”

Washington’s thoughts were elsewhere, and he didn’t reply.

The deer were being butchered. Hearts and livers were set on bark trenchers, intestines set aside, and haunches separated even as they watched. The older women moved from carcass to carcass providing advice while the younger women did all the work and got coated in the blood and ordure. The whole process seemed to take no time at all, Dr. Craik had never seen the like and watched, fascinated. The other two white men seemed oblivious to the spectacle, the tall one standing with his coffee, the small one sitting by him with his rum. Some of the native men were sitting with Nicholson; the older men had gathered in a knot around the smoker, who was now passing his pipe. None showed any curiosity about the strangers.

Pompey walked up behind his master and took the empty horn cup.

“Dat be trouble, suh.” He inclined his head, the slightest gesture toward their tent.

One of the younger women had a white ruffled shirt on. It was clean and probably out of their equipment. Other women were laughing at her. They were also stealing glances at Dr. Craik. Craik remained oblivious for a moment, and then his thin face grew mottled with red.

“Doctor.” The tall man put a restraining hand on his shoulder.

“That woman has my shirt on!”

“Pay her no attention, Doctor.”

“I’ll have my shirt back.”

“You may take one of mine. We are in their country, and they are testing us. Think of it as the price of dinner. Resent the next theft, but not the first.”

Nicholson nodded curtly and called something across the camp. One of the older women roared. The others looked uneasy.

None of the men had stirred, but their attention seemed to focus on the whites for the first time. It made Dr. Craik feel uneasy. There was menace to it, an alien scrutiny from beyond his world of manner and custom.

“She looks a damn sight better in that shirt than you, Doctor.” Nicholson settled himself back against his tree and set to getting a spark on to some charcloth for his pipe.

Craik took a deep breath and made himself smile. “She does, the vixen. Even with shirts at six shillings apiece and not to be bought in this country.”

Nicholson was busy pulling at his pipe, clay turned black with use. He had laid his tiny scrap of lit char atop the bowl and was drawing the coal down into the tobacco. He was so fast with his flint and steel that Craik had missed the spark. When it was alight, he puffed for a moment, looking hard at Craik from under his unkempt eyebrows.

“Look at yon, Doctor. The men don’t show what they think, and nor should you. Angry or happy, keep your thoughts to yourself. Now, when they’re in drink, mind, then it’s the strongest to the fore and de’il take the hindmost.”

“He seems easy with them.”

“Oh, aye. Well, he doesna give much away, our colonel. And he stands tall. But mostly he’s a name to them. The chief there, he marked him soon as we rode in, an’ that counts for something.”

“It’s like another country.”

“It is another country, Doctor. This is the wilderness. He knows, and I know. Even Pompey knows. You were here in the war?”

“With the Provincials.”

“Well, now you’re with the savages. Best learn to please ’em.” The man laughed.

Craik wanted to resent his tone, but the advice was kindly given, even from a low Scots Borderer with rum on his breath and an old plum greatcoat, and the tension seeped out of his shoulders.

“That’s right, Doctor. Dinna fash yersel. Dram?”

Before night fell, the camp took on new life and new smells as the best of the deer went on to the fires. The men made a circle on the grass, some on blankets or robes, some already sprawled from the effects of Nicholson’s rum. The women cooked and moved about, a separate community from the men, still at work while the men took their ease. Craik was handed a large mound of meat on a bark platter by the girl wearing his shirt, and he smiled at her, but she didn’t meet his eyes. He wondered for a moment what he looked like to her, or to any of them. Handsome? Ugly? The shirt already had a line of black across one shoulder, and a red handprint on the back.

He took out his traveling case and unfolded his fork before cutting the meat. One of Washington’s blacks handed round a horn with salt and pepper. The savages just sat and ate, men with men, women off to one side.

Washington spoke into the stillness and the sound of many jaws working.

“Ask him from where he knows me, Mr. Nicholson.”

Nicholson spoke without slowing his meal. The old man put his pipe down on his robe and leaned forward a little, his whole attention on Washington.

“He says he nearly took you at the Monongahela.”

“Tell him I was too young to know one warrior from another.”

“He says you were guarded from his gun, and hopes you have a great future.”

“Ask him to tell it.”

The old man spoke for a moment, his right hand moving as if pointing at invisible things. Washington, too, looked at the invisible things. For the second time in a day, he thought of that bitter hour. All around them, the younger warriors stirred and settled themselves, even the drunk ones craning their heads to listen. The old man started, a sing-song quality to his narration, as if the beginning had been related many times, which it had. Nicholson picked it up almost immediately, listening and speaking with conviction, mere words behind his host. It was quite a feat, only the occasional occurrence of Scots Border brogue interrupting the impression that the old man was speaking the English himself.

“I was with the French captain at the first discharge, and he fell. We fired back at the high-hats and killed many, and they broke. Then we spread to the woods on either side of the trail. I killed four men in as many shots. Then I moved again, farther off the trail. Many warriors followed me. We fired and ran, fired and ran, trying to circle to the back. For many minutes, I didn’t know who was taking the worst of it.”

Washington held up his hand for a moment. “Did you go to the left of the trail, or the right?”

Nicholson cocked his head to listen to the old man, then nodded.

“We went up the hill, he says. He thinks that answers you.” Washington nodded.

“After some time we found a little hill with thick trees and we stayed there, firing into the men below us. That was the first time I shot at you. You were on a fine horse. I shot at you and hit the horse.”

“I remember that.” Washington looked into the fire. The battle was not yet a disaster. The grenadiers of the Forty-fourth, the only veterans in the regiment, had formed at the base of that deadly little hill. They kept up a hot fire, and Washington’s Virginians had started to gather on their flanks, staying behind trees but shooting steadily. Some of the raw battalion men of the Forty-fourth had begun to rally from their initial panic. Washington had just asked the grenadier captain to take the hill when his horse went down.

Nicholson paused in his translation to drink, but Washington was still there, kicking his feet free of the stirrups and sliding over the crupper, his boot pulls caught in the buckles of his saddlebag. By the time he was on his feet, the young captain had his jaw shot away, a third of the grenadiers were down, and they were past saving, the recruits and the Virginians with them.

It marked the bitterest moment of his life. The moment in which he knew that they were beaten, that the whole expedition, the empire, the army, the foundations of the world were undone.

Nicholson wiped his mouth and went on.

“You disappeared when the high-hats ran. I followed you. There was nothing to stop us—most of the English had stopped shooting. The next time I saw you, you were with the big general. He was struggling with his horse. I think it was hit. I tried for you again. Perhaps I hit the general. It is possible. He fell. You caught him. You and others carried him off and I couldn’t follow in the press.”

Washington nodded.

“I thought I’d lost you. Then, right at the end, there you were, all alone, sitting on another tall horse.”

Washington looked back into the fire. It was not a moment he liked to dwell on. He had ridden back into the rout and perhaps he had hoped to be killed. He couldn’t remember that part with any clarity, but it came to him some nights, when there were bills due in England or a crop failed.

“My musket was empty, and I started loading it. You yelled at some men running by, but you didn’t move. That is when it came to me that you had a spirit and it was not your day to die, and I thought I will take him for my own, and his spirit will join my clans. Others fired at you. I saw you pull a long pistol and shoot it somewhere else, and I was just ramming my ball home. I pulled the rammer clear and threw it down to get a faster shot, and I began to run toward you. You just sat. You never saw me. When I was almost close enough to touch you, as close as I am now, a boy came at me out of the brush. He spooked your horse. And I hit him with my club, but you were moving away. Indeed, I took him. Since I already had my captive, I thought I would kill you. I looked down the barrel and pulled the trigger, and the pan flashed, and no shot came, and still you rode. Then I looked down at the lock, as one does…you know?”

Washington nodded, a brother in the fraternity of men frustrated by the vagaries of flintlocks.

“When I had the priming back in, you were gone.”

The old man was done before Nicholson, and he looked at Washington and smiled. He pointed to a young man in an old French coat.

“It happens often to Gray Coat here when he hunts deer, but not to me.”

Most of the warriors laughed, although the one man looked sour.

“I should have ignored the boy, although he made a good slave, for a while. My mother adopted him, and he was with us until the Pennsylvania men made us send him away.”

Washington smiled, but he had rather the look of Gray Coat the moment before. The old man raised his hand, and smiled a feral smile.

“I should have killed him and taken you. I still wonder what kind of a slave you would have made.”

Mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, November 6, 1773

“You clap on to that line and haul, laddie. That’s it. Handsomely now, you lot. Pull. Pull, you black bastards. Belay there, King. Right.” High overhead the newly fished spar rose into the dawn light and was seated home against the mast. The black men on the deck hauled and sweated, but the sailors sweated just as hard.

The squall had hit them inside the capes, laying the vessel on her beam-ends, stripping off every scrap of sail and cracking the fore-topsail yard. The sailor called King, a free black, had cut the broken yard away from the rigging it threatened to shred, standing on the canted deck with the ropes’ ends pounding him like a dozen fiendish whips.

The ship’s master, Gibson, had shipped a small cargo of West Indies blacks to augment the rum and molasses in the hold. They were skilled men: two bricklayers, a carpenter, a huntsman, and a gunsmith, all likely to fetch first-rate prices among the Virginia gentry. In the meantime, they could haul ropes in an emergency.

High above them, King waved at the captain and leaned out, grabbing a stay and sliding for the deck. Something King saw at the last moment of his slide halted him, and he ran his eyes over the group standing in the waist of the ship, still holding the line that had raised the yard. One young man had scars over his eyes, hard ridges that told a story, if the watcher knew what to read. King wandered over, acknowledging the praise of his shipmates and some good-natured abuse. He turned to the man with the scars, a wave of homesickness hitting his breast and slowing his breath.

“Hello, cousin.”

The man’s eyes widened for a moment, then his white teeth flashed in an enormous smile.

“Greetings, older cousin.”

The man looked young, young to have left home with the scars of a warrior and already have a skill worth selling in America. His face was not yet hard or closed as the slaves’ too often were.

“I honor your courage in the storm, older cousin.” Nicely phrased. King smiled himself, but turned away, headed for his hammock. It didn’t do to associate too much with slaves, at least where white men could see you. It gave them ideas.

King returned topside at the changing of the watch, to see the familiar low Virginia shore clear to the southwest. The Chesapeake had become confused in his memories with Africa, where great rivers ran deep into the woods, and he thought of Virginia as home, the place where he had a wife and a family. He stood by the heads watching the shore for a moment, and then moved into the waist. The sails were set and, barring a disaster, wouldn’t need to be touched until the turn of the tide. Until a crisis came, sailoring was an easy life, and King liked a crisis here and there. They made good stories.

The young one with scars was watching him from the group of slaves at the base of the mainmast. It was a polite regard: the youth didn’t stare, but simply glanced his way from time to time, as if inviting him to speak. King settled into the shade of the sail with the other crew on deck and accepted a draw from another man’s pipe. There were sailors who wouldn’t smoke with a black man, but not many around King. Gibson preferred English sailors to Americans. King had noticed that Englishmen seemed easier with blacks. It didn’t stand to reason.