Полная версия:

The Later Roman Empire

AVERIL CAMERON

THE LATER ROMAN EMPIRE

AD 284–430

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Introduction to the Fontana History of the Ancient World

Preface

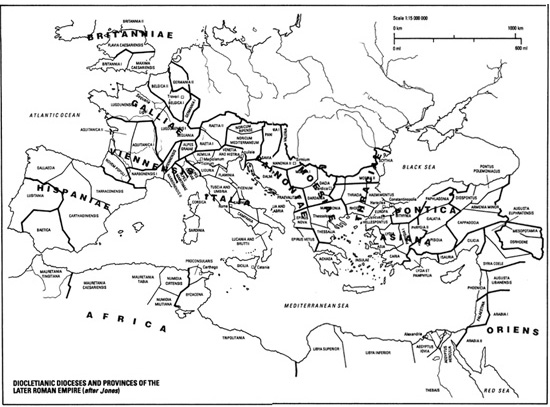

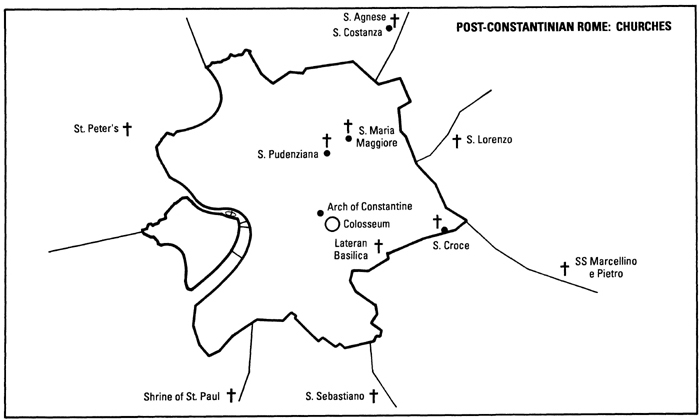

Maps

I Introduction: the third-century background

II The Sources

III The New Empire: Diocletian

IV The New Empire: Constantine

V Church and State: The Legacy of Constantine

VI The Reign of Julian

VII The Late Roman State: Constantius to Theodosius

VIII Late Roman Economy and Society

IX Military Affairs, Barbarians and the Late Roman Army

X Culture in the Late Fourth Century

XI Constantinople and the East

XII Conclusion

Date Chart

List of Emperors

Primary Sources

Further Reading

Appendix

Index

About the Author

Fontana History of the Ancient World Series

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction to the Fontana History of the Ancient World

NO JUSTIFICATION is needed for a new history of the ancient world; modern scholarship and new discoveries have changed our picture in important ways, and it is time for the results to be made available to the general reader. But the Fontana History of the Ancient World attempts not only to present an up-to-date account. In the study of the distant past, the chief difficulties are the comparative lack of evidence and the special problems of interpreting it; this in turn makes it both possible and desirable for the more important evidence to be presented to the reader and discussed, so that he may see for himself the methods used in reconstructing the past, and judge for himself their success.

The series aims, therefore, to give an outline account of each period that it deals with and, at the same time, to present as much as possible of the evidence for that account. Selected documents with discussions of them are integrated into the narrative, and often form the basis of it; when interpretations are controversial the arguments are presented to the reader. In addition, each volume has a general survey of the types of evidence available for the period and ends with detailed suggestions for further reading. The series will, it is hoped, equip the reader to follow up his own interests and enthusiasms, having gained some understanding of the limits within which the historian must work.

OSWYN MURRAY

Fellow and Tutor in Ancient History,

Balliol College, Oxford

General Editor

Preface

THE MAIN IDEAS and emphases expressed in this book and its companion volume, The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity, AD 395–600, Routledge History of Classical Civilization (London, 1993), have evolved over twenty or so years of teaching and lecturing. Although during that period the later Roman empire has become fashionable, especially in its newer guise of ‘late antiquity’, there is still, strangely, no basic textbook for students in English. I am very glad therefore to have been given this opportunity to attempt to fill that gap. My own approach owes a great deal to the influence over the years of my colleagues in ancient history, especially to those who have been associated with the London Ancient History Seminars at the Institute of Classical Studies. Not least among them is Fergus Millar, who initiated the seminars, and who both encouraged a broad and generous conception of ancient history and insisted on the great importance of lucid and helpful presentation. Most important of all, however, have been the generations of history and classics students, by no means all of them specialists, who have caused me to keep returning to the old problems, and to keep finding something new.

This book was written at speed, and with great enjoyment, partly as a relief from more difficult and recalcitrant projects. Though of course infinitely more can be said than is possible in this limited compass, I hope that it will at least provide a good starting point from which students can approach this fascinating period. It is a characteristic of this series to embody translated excerpts from contemporary sources; in the case of Ammianus Marcellinus, such translations are taken from the Penguin edition by W. Hamilton. I am grateful to the editor of the series, Oswyn Murray, for wise guidance, and to several others for various kinds of help, notably to Dominic Rathbone and Richard Williams. But they, needless to say, had no part in the book’s defects.

London, August 1992

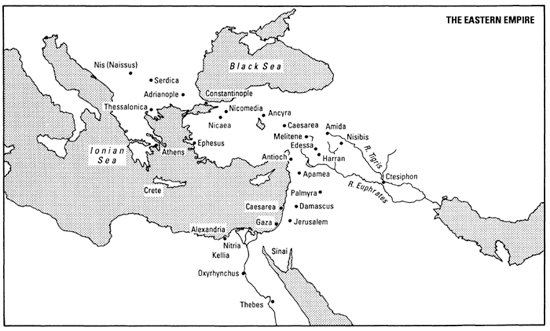

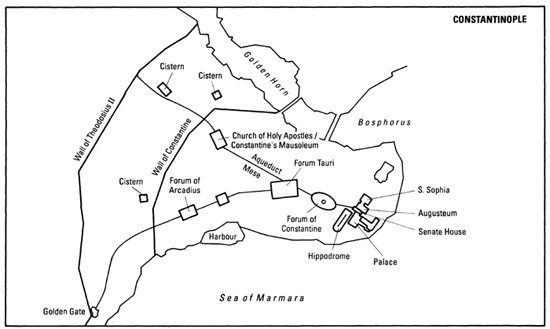

Maps

I Introduction THE THIRD-CENTURY BACKGROUND

IT IS A MARK OF the dramatic change that has taken place in our historical perceptions of the ancient world that when the new Fontana series was first launched, the later Roman Empire, or, as it is now commonly called, late antiquity, was not included in it; now, by contrast, it would seem strange to leave it out. Two books of very different character were especially influential in bringing this change about, so far as English-speaking students were concerned: first, A. H. M. Jones’s massive History of the Later Roman Empire. A Social, Economic and Administrative Survey (Oxford, 1964), and second, Peter Brown’s brief but exhilarating sketch, The World of Late Antiquity (London, 1971). Of course, the subject had never been neglected by serious scholars, or in continental scholarship; nevertheless, it is only in the generation since the publication of Jones’s work that the period has aroused such wide interest. Since then, indeed, it has become one of the major areas of growth in current teaching and research.

The timespan covered in this book runs effectively from the accession of Diocletian in AD 284 (the conventional starting date for the later Roman empire) to the end of the fourth century, when on the death of Theodosius I in AD 395 the empire was divided between his two sons, Honorius in the west and Arcadius in the east. It is not therefore so much a book about late antiquity in general, a period that can plausibly be seen as running from the fourth to the seventh century and closing with the Arab invasions, as one about the fourth century. This was the century of Constantine, the first emperor to embrace and support Christianity, and the founder of Constantinople, the city that was to become the capital of the Byzantine empire and to remain such until it was captured by the Ottoman Turks in AD 1453. Edward Gibbon’s great work, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, carries the narrative to the latter date, regarding this, not AD 476, when the last Roman emperor in the west was deposed, as the real end of the Roman empire. Few would agree with Gibbon now, but historians are still quarrelling about when Rome ended and Byzantium began, and in their debate Gibbon’s highly-coloured perception of the moral decline which he thought had set in once the high point of Roman civilization under the Antonine emperors in the second century AD was passed remains highly influential. All writers on the fourth century must take a view about what are in fact highly subjective issues: was the regime of the later empire a repressive system which evolved in response to the chaos which had set in in the third century? Can we see in it the signs of a decay which led to the collapse and fragmentation of the Roman empire in the west in the fifth century? Did Constantine’s adoption of Christianity somehow assist a process of decline by finally abandoning earlier Roman values, as Gibbon thought?

All these views have been and still are widely held by historians, and permeate much of the writing on the period. It will soon be clear that this book takes a different approach. Preconceptions, and especially value judgements, cannot be avoided altogether in a history, but they certainly do not help either the historian or the student. Moreover, we are much less likely today, given the challenge to traditional values which has taken place in our own society, to hold up the Principate as the embodiment of the classical ideal, and to assume that any deviation from it must necessarily represent decline. Finally, we are perhaps more wary than earlier generations of historians of the power and the dangers of rhetoric, and less likely than they were to take the imperial rhetoric of the later Roman empire at face value. The period from Diocletian onwards is sometimes referred to as the ‘Dominate’, since the emperor was referred to as dominus (‘lord’), whereas in the early empire (the so-called ‘Principate’), he had originally been referred to very differently, simply as princeps (‘first citizen’). But the term dominus was by no means new; moreover, what the fourth-century emperors wanted, and how they wanted to appear, was one thing; what kind of society the empire was as a whole was quite another.

To gauge the difference, we must start not with Diocletian or the ‘tetrarchic’ system which he instituted in an attempt to restore political stability – according to Diocletian’s plan, two emperors (Augusti), were to share power, each with a Caesar who would in due course succeed him. We must start rather with the third century, the apparent watershed between two contrasting systems. Here, traditionally, historians have seen a time of crisis (the so-called ‘third-century crisis’), indicated by a constant and rapid turnover of emperors between AD 235 and 284, by near-continuous warfare, internal and external, combined with the total collapse of the silver currency and the state’s recourse to exactions in kind. This dire situation was brought under at least partial control by Diocletian, whose reforming measures were then continued by Constantine (AD 306–37), thus laying the foundation for the recovery of the fourth century. In such circumstances, for which it is not difficult to find contemporary witnesses, it is tempting to imagine that people turned the more readily to religion for comfort or escape, and that here lie the roots of the supposedly more spiritual world of late antiquity. But much of this too is a matter of subjective judgement, and of reading the sources too much at face value. Complaints about the tax-collector, for instance, such as we find in rabbinic sources from Palestine and in Egyptian papyri, tell us what we might have expected anyway, namely that no one likes paying taxes; they do not tell us whether the actual tax burden had increased as much as they seem at first sight to imply. While there certainly were severe problems in the third century, particularly in relation to political stability and to the working of the coinage, nearly all the individual components of the concept of ‘third-century crisis’ have been challenged in recent years. And if the crisis was less severe than has been thought, then the degree of change between the second and the fourth centuries may have been exaggerated too.

‘The third-century crisis’, ‘the age of transition’, ‘the age of the soldier-emperors’, ‘the age of anarchy’, ‘the military monarchy’ – whatever one likes to call it, historians are agreed that the critical period in the third century began with the murder of Alexander Severus in AD 235 and lasted until the accession of Diocletian in AD 284. The first and most obvious symptom to manifest itself was the rapid turnover of emperors after Severus – most lasted only a few months and met a violent end, often at the hands of their own troops or in the course of another coup. Gallienus (253–68) lasted the longest, while Aurelian (270–5) was the most successful, managing to defeat the independent regime which Queen Zenobia had set up at Palmyra in Syria after the death of her husband Odenathus. But Valerian (253–60) was captured by Shapur I, the king of the powerful dynasty of the Sasanians who had succeeded the Parthians as the rulers of Persia in AD 224, while from AD 258 to 274, Postumus and his successors ruled quasi-independently in Gaul (the so-called ‘Gallic empire’).

This turnover of emperors (the distinction between emperor and usurper became increasingly blurred) was intimately linked with the second symptom of crisis, constant warfare, which furnished an even greater role for the army, or armies, than they had already played under the Severans. The Sasanians presented a serious and unforeseen threat to the east which was to last for three hundred years, until the end of their empire after the victories of Heraclius in AD 628. Conflict with the Sasanians was to exact a heavy toll in Roman manpower and resources. Their greatest third-century king, Shapur I (AD 242–c.272), set a pattern by invading Mesopotamia, Syria and Asia Minor in AD 253 and 260, taking Antioch and deporting thousands of its inhabitants to Persia; he recorded his victories in a grandiose inscription at Naqsh-i-Rustam, with reliefs showing the humiliated Emperor Valerian. To the north and west Germanic tribes continued to exert the pressure on the borders which had caused such difficulty for Marcus Aurelius, and, before Valerian’s capture by Shapur, Decius had already been defeated by the Goths (AD 251). The underlying reasons for the continued barbarian raids and the actual aims of the invaders are still far from clear. It is a mistake to think in apocalyptic terms of waves of thousand upon thousand of barbarians descending on the empire, for the actual numbers on any one occasion were quite small. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that in these incursions the third century saw the prototype of another problem which was to assume a great magnitude in the later empire, and to which was to be accorded, by many historians, primary responsibility for the fall of the western empire. At one time or another virtually all the northern and western provinces suffered barbarian invasion, as did Cappadocia, Achaea, Egypt and Syria, and Italy itself was not exempt under Aurelian. Contemporaries could be forgiven for seeing this as the beginning of the end.

The army had already assumed far more importance than before as a result of Septimius Severus’s reforms, and the critical situation in the third century gave it a dangerous preeminence. Not surprisingly, each provincial army put forward its own candidate for emperor, and as quickly murdered him if they so chose. There was nothing to stop the process being repeated: the senate had never controlled armies directly, and even if there was an emperor in Rome he had little chance in such disturbed conditions of controlling what happened on the periphery of the empire. It was not so much that external military threats caused internal instability (though they certainly contributed), but rather that they fell on an empire which was already highly unstable, as had been vividly shown in the civil wars which broke out from the reign of Marcus Aurelius onwards. In the third century, however, further consequences soon appeared: the army necessarily increased in size, and thus in its demands on resources, and in contrast to the peaceful conditions of the early empire when soldiers were on the whole kept well away from the inner provinces, they were now to be found everywhere, in towns and in the countryside, and by no means always under control. When a more stable military system was reintroduced by Diocletian and Constantine, the situation was in part recognized as given, and the army of the later empire, instead of being largely stationed on the frontier, was dispersed in smaller units inside provinces and in towns.

Not surprisingly in such circumstances, the military pay and supply system broke down under the strain. The army had been paid mainly in silver denarii, out of the tax revenues collected in the same coin. The silver content of the denarius had already been reduced as far back as the reign of Nero, but from Marcus Aurelius on it was further and further debased, while the soldiers’ pay was increased as part of the attempt to keep the army strong and under control. The process was carried to such lengths that by the 260s the denarius had almost lost its silver content altogether, being made virtually entirely of base metal. It may seem surprising that prices had not risen sharply as soon as the debasements had begun in earnest. But the Roman empire was not like a modern state, where such changes are officially announced and immediately effected. Communication was slow, and the government, if such a term can be used, had few means open to it of controlling coins or exchange at local levels even at the best of times, and certainly not in such disturbed conditions. The successive debasements, which were to have such serious consequences, were much more the result of ad hoc measures taken to ensure continued payment of troops than of any long-term policy. But naturally prices did rise, and rapidly, causing real difficulties in exchange and circulation of goods. This is not inflation in the modern sense; rather, it was the result of very large amounts of base-metal coins being produced for their own purposes by the fast-changing third-century emperors, and of the gradual realization by the populace that current denarii were no longer worth anything like their face value. The inevitable effect of this was to push older and purer coins out of circulation, and indeed a large proportion of the Roman coins now preserved derive from hoards apparently deposited in the third century. Gold and silver disappeared from circulation at such a rate that Diocletian and Constantine had to institute special taxes payable only in gold or silver in order to recover precious metals for the treasury. Once the spiral had been set in motion, it was even harder to stop, and despite Diocletian’s efforts at controlling prices, papyrological evidence shows that they were still rising dramatically under Constantine.

This is the background to the return to exchange in kind which many historians have seen as a reversion to a primitive economy and therefore a key symptom of crisis. Not merely were the troops partly paid in goods instead of in money; taxes were collected in kind too, the main drain on tax revenue having always been the upkeep of the army. But especially in view of the experience of our own world, we should be less struck by the retreat from monetarization than by the success with which an elaborate system of local requisitions was defined and operated, and needs matched to resources. It is also relevant to note that direct exactions had always been part of Roman practice in providing for the annona militaris, the grain supply for the army, and the angareia, military transport; it was not the practice itself that was new, but the scale. But conditions were extremely unstable, especially in the middle of the century, and local populations were liable to get sudden demands without warning which caused real hardship; it was left to Diocletian to attempt to systematize the collections by regularizing them.

If the army was, if only partly, being paid in kind (money payments never ceased altogether) other consequences followed, for instance the need for supplies to be raised from areas as near as possible to the troops themselves, for obvious reasons connected with the difficulty of long-distance transport. We find the fourth-century army, therefore, divided into smaller units posted nearer to centres of distribution. Again, there were changes in command: the praetorian prefects, having started as equestrian commanders of the imperial guard, had gradually taken on more general army command functions; with these changes in the annona and requisitions generally, they effectively gained charge of the provincial administrative system, and were second in power only to the emperor. In a similar way equestrians in general acquired a much bigger role in administration, for instance in provincial governorships, traditionally held by senators. Later sources claim that Gallienus excluded senators by edict from holding such posts (Aur. Vict., Caes. 33.34), but it is clear that there was never a formal ban, and some did continue; the change is more likely to have been the natural result of decentralization and of the breakdown of the patronage connection necessary for such appointments between the emperor in Rome and the members of the senatorial class. It was more practical, and may have seemed more logical, for emperors raised in the provinces and from the army, as most were, to appoint governors from among the class they knew and had to hand.

The Senate’s undoubted eclipse in the third century is partly attributable to the fact that emperors no longer resided or were made at Rome; the close tie between emperor and Senate was therefore broken, and few third-century emperors had their accessions ratified by the Senate according to traditional practice. Meanwhile the Senate itself lost much of its political role, though membership continued to bestow prestige and valuable fiscal exemptions. Rather than owing their elevation to the Senate, therefore, emperors in this period were often raised to the purple on the field, surrounded by their troops. The legacy of this dispersal of imperial authority can still be seen under Diocletian and the tetrarchy, when instead of holding court at Rome the Augusti spent their time travelling and residing at a series of different centres such as Serdica and Nicomedia, some of which, in particular Trier and Antioch, had already acquired semi-official status in the third century. Rome was never to become a main imperial residence again. Moreover, Rome and the Senate had always gone together. But Constantine now put the senatorial order on a new footing by opening it more widely, so that membership became empire-wide rather than implying a residence and a function based on Rome itself.

In fact, the mid-third century did not see a dramatic crisis so much as a steady continuation of processes already begun, which in turn led to the measures later taken by Diocletian and Constantine that are usually identified with the establishment of the late Roman system. How therefore should the evidence of monetary collapse be assessed in this context? This is one of the most difficult questions in trying to understand what was actually happening. We need to ask how far rising prices were due to a general economic crisis and how much they were the result of a monetary collapse caused by quite specific reasons. One phenomenon often cited in support of the former argument is the virtual cessation of urban public building during this period. The local notables who had been so eager to adorn their cities with splendid buildings during the heyday of Roman prosperity in the second century no longer seemed to have the funds or the inclination to continue. The kind of civic patronage often known as ‘euergetism’ from the Greek word for ‘benefactor’, that had been so prominent a feature of the early empire, now came to a virtual halt. From the fourth century onwards the economic difficulties of the town councils become a major theme in the sources. But a drop in the fortunes of the upper classes is only one possible explanation for the cessation of building; it is clear that the upkeep of existing public buildings, which fell on the city councils, was already a problem by the late second century. Further additions to the stock might be an embarrassment rather than a cause for gratitude. By the mid-third century the uncertainty of the times in many areas also made the thought of building, as of benefactions in the old style, seem inappropriate; in cities which felt themselves vulnerable to invasion or civil war, the first interest of town councils was simply in survival or indeed repair. Some cities showed considerable resilience even after severe attack. Antioch and Athens were badly damaged by the Sasanians and the Heruli respectively, yet both were able to recover. By contrast, the cities in Gaul which suffered during the third-century invasions were more vulnerable than those in the more prosperous and densely populated east, and when rebuilding and fortification took place their urban space typically contracted, as at Amiens and Paris. While in the early empire cities had not needed strong defences, they now started to acquire city walls, and to change their appearance into the walled city typical of late antiquity. At Athens itself the area north of the Acropolis was now fortified. But in North Africa the situation was different again. There, the third century saw continued building and urban growth. Protected to some extent from the insecurity elsewhere, the North African economy profited from increased olive production, and the cities of North Africa in the fourth century were among the most secure and prosperous in the empire.