скачать книгу бесплатно

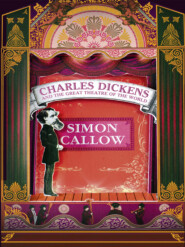

Charles Dickens and the Great Theatre of the World

Simon Callow

An entertaining biography of Dickens by one of our finest actorsAcclaimed actor and writer Simon Callow captures the essence of Charles Dickens in a sparkling biography that explores the central importance of the theatre to the life of the greatest storyteller in the English language.From his early years as a child entertainer in Portsmouth to his reluctant retirement from ‘these garish lights’ just before his death, Dickens was obsessed with the stage. Not only was he a dazzling mimic who wrote, acted in and stage-managed plays, all with fanatical perfectionism; as a writer he was a compulsive performer, whose very imagination was theatrical, both in terms of plot devices and construction of character.Like many actors, Dickens felt the need to be completed by contact with his audience. He was the original ‘celebrity’ author, who attracted thousands of adoring fans to his readings in Britain and across the Atlantic, in which he gave voice to his unforgettable cast of characters.In Charles Dickens and the Great Theatre of the World, Callow brings his own unique insight to a life driven by performance and showmanship. He reveals an exuberant and irrepressible talent, whose ‘inimitable’ wit and personality crackle off the page.

Charles Dickens and the Great Theatre of the World

Simon Callow

Dedication

This book is dedicated to a friend whose loss

only gets worse with the passing years, Simon

Gray (1936–2008), superb dramatist, sublime

diarist, intoxicating conversationalist, who was

more alive to Dickens, and in whom Dickens

was more alive, than anyone I ever knew. Much

of what is in this book was first floated during

hours and hours of Dickensian chat in

restaurants across the city during twenty-five

golden years of friendship.

Contents

Cover (#ulink_27716552-d192-5ccb-8ab4-c30e5d5fb634)

Title Page

Dedication

Foreword

Overture

1 Paradise

2 Paradise Lost

3 Beginning the World

4 The Birth of Boz

5 The Peregrinations of Pickwick

6 Practical Power

7 Here We Are!

8 Sledge-Hammer Blow

9 Animal Magnetism

10 Every Man in His Humour

11 The Great Fight and Strife of Life

12 Not So Bad as We Seem

13 The Ice-Bound Soul

14 Going Public

15 The Loadstone Rock

16 On the Ground

Acknowledgements

Select Bibliography

Searchable Terms

Copyright

About the Publisher

FOREWORD

When he was a young graduate, Michael Slater, the current doyen of Dickens studies, was asked by his tutors at Oxford what he wanted to study for his PhD. When he said ‘Dickens’, they looked at him aghast. Dickens was simply not part of the accepted canon. After vainly trying to dissuade him, they sent him off to Another University for advice and guidance, after which he then commenced his life’s work, to the benefit of all Dickensians everywhere. Half a century later, the situation is entirely reversed: there is a non-stop tsunami of scholarly studies of Dickens from every possible angle. Dickens and Women, Dickens and Children, Dickens and Food, Dickens and Drink, Dickens and the Law, Dickens and Railways, Dickens and the Americans, Dickens and Europe, Dickens and Homosexuality, Dickens and Magic, Dickens and Mesmerism, Dickens and Art, Dickens and Stenography, Dickens and Publishing. As yet, I have not come across a book on Dickens and Dogs, but it can only be a matter of time: a perfectly interesting and not especially slim volume is just waiting to be written. The multifarious-ness of Dickens makes him virtually inexhaustible as a subject. These studies have run alongside and to some extent been the outcrop of the huge transformation in academic attitudes to Dickens, particularly with regard to the later novels, which were largely dismissed by critical opinion in his lifetime.

There has also been a magnificent procession of major biographies, from Edgar Johnson in the 1950s to Fred Kaplan in the 1980s, Peter Ackroyd’s sublime act of creative self-identification with Dickens in the 1990s, Michael Slater’s revelatory account of, as he puts it, a life defined by writing, to the most recent, Claire Tomalin’s vivid survey of the Life and Work. Dickens has never been more present. So it takes some cheek on the part of one who is by no means a Dickens scholar to offer yet one more account of the man who called himself Albion’s Sparkler. I dare to do so because my relationship to the great man is a little different from anyone else’s. In an exchange that Dickens himself might have relished, the late dramatist Pam Gems went to see one of her plays performed by that fine actor Warren Mitchell. She noticed that one or two lines in the text had changed. Reproached by her, Mitchell replied, ‘Pam, Pam: you only wrote ’im. I’ve been ’im.’ I have, over the years, been Dickens in various manifestations, from reconstructions of the Public Readings on television, to one of Dr Who’s helpers; I have also been involved in telling his life story, through the wonderful play that Peter Ackroyd wrote for me, The Mystery of Charles Dickens. Presently I am involved in performing two of his monologues, Dr Marigold and Mr Chops, and his solo version of A Christmas Carol. In order to do all of this, I have needed to find out what it was like to be him, and what it was like to be around him. I have immersed myself, on an almost daily basis, over a period of nearly fifteen years, in the minutiae of his life, above all seeking out personal reminiscences and his own utterances rather than exegetic texts.

Over the years, since a thoughtful grandmother thrust a copy of The Pickwick Papers into my hands as I repined in the itchy agony of chicken pox – from the moment I started reading, I never itched again – I have read virtually everything he has written, with the mixture of joy and frustration that all readers of Dickens except for fundamentalists experience. But it is not the writing that is the focus of the present book: when the content of a novel is autobiographical (which to one degree or another many of them are), I have of course discussed it, but my primary concern has always been to convey the flavour of one of the most remarkable men ever to walk the earth: vivacious, charismatic, compassionate, dark, dazzling, generous, destructive, profound, sentimental – human through and through, an inspiration and a bafflement.

Inevitably, as the title of the book declares, I have focused on the theatre in Dickens’s life. In recent years there has been an exceptional sequence of books that analyse the influence of the theatre on Dickens’s work in subtle and deeply illuminating ways – books by Robert Garis, Paul Schlicke, Deborah Vlock, Malcolm Andrews, John Glavin. Again, this is not the territory of the present book, which looks at the histrionic imperative so deeply rooted in Dickens, but beyond that is interested in Dickens on the stage of life, as he would certainly have thought of it. I have always been concerned with the peculiar quality of his personality, described with remarkable consistency by his contemporaries as theatrical. The books, therefore, to which I have had most recourse are the ones that have given me the man as he lived and breathed: Forster’s richly moving three-volume Life, the very first biography, written by the man who knew him better than anyone else, and whose perpetual sense of astonishment at his friend sings out on every page; the glorious twelve-volume Pilgrim Edition of the Letters, wherein Dickens speaks again, fresh, funny, tortured by turns; the Speeches, edited by Fielding, all improvised but faithfully transcribed to give a unique sense of Dickens the public man; Philip Collins’s wonderful collection of reminiscences and interviews; and the superb and constantly illuminating chronology by Norman Page, which in its dry way gives as well as anything written a sense of the sheer amount of abundant living that Dickens crammed into his rather short life. In the end, of course, this biography, as with any other, is a selection of the man: playing Dickens, and performing his work, has been like standing in front of a blazing fire. If I can convey any sense of that, I will have succeeded in my aim.

OVERTURE

A very small, rather frail child is escorted into a pub in Chatham, in Kent, by a plump, vivacious man. The man, exchanging affable words with the population of the pub, who all know him well, places his child on a table and enjoins him to recite. Though afflicted with a slight lisp, which he will never entirely lose, the child gives a startlingly vivacious rendition of that noted improving lyric, ‘The Sluggard’, one of the Divine Songs for Children from the prolific pen of the Revd Dr Isaac Watts.

’Tis the voice of the sluggard; I heard him complain,

‘You have waked me too soon, I must slumber again.’

As the door on its hinges, so he on his bed,

Turns his sides, and his shoulders, and his heavy head.

‘A little more sleep, and a little more slumber;’

Thus he wastes half his days, and his hours without number;

And when he gets up, he sits folding his hands,

Or walks about saunt’ring, or trifling he stands …

I made him a visit, still hoping to find

He had took better care for improving his mind:

He told me his dreams, talk’d of eating and drinking;

But he scarce reads his Bible, and never loves thinking.

Said I then to my heart, ‘Here’s a lesson for me,’

That man’s but a picture of what I might be:

But thanks to my friends for their care in my breeding;

Who taught me betimes to love working and reading.

The rendition was a great success: ‘the little boy used to give it to great effect, and with such actions and such attitudes,’ said the family maid, Mary. It was a modest debut for the greatest literary entertainer of all time, but the seven-year-old Charles Dickens obviously took the moral of the poem to heart: no human being on the face of the earth ever filled his waking moments to better effect than he, cramming his fifty-eight years with an astonishing variety of performances in a multiplicity of arenas.

ONE

Paradise

Dickens’s arrival in the world was announced with a flourish in the Portsmouth newspapers on Monday, 10 February 1812: ‘BIRTHS: On Friday, at Mile-End Terrace, the Lady of John Dickens, Esq. a son.’ The phrase has a certain gallantry about it, archaic even for the time, an almost chivalric floridity entirely characteristic of John Dickens. He was born, in 1785, in Crewe House in London and grew up in Crewe Hall, the stately Jacobean mansion in Cheshire in which his father William had been the butler. William died before John was born, but his widow Elizabeth remained housekeeper, a pivotal figure in the running of the Crewe family’s various splendid and extensive establishments. Crewe Hall was a very grand household, and a hotbed of Whiggish political activity; among the regular guests were the politicians Charles James Fox, George Canning and Edmund Burke, the playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan and the painters Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Lawrence: some of the greatest men of the age. As a boy and a youth, John Dickens would inevitably have been involved in his mother’s work, becoming a player, if only in a bit part, in the highly theatrical enterprise of running a great house: a carefully staged performance, with sharply defined spheres of backstage and onstage, rigidly maintained roles and a script to be departed from only in exceptional circumstances.

Certainly John Dickens emerged from that world with an orotundity, above all an elaborate sense of language, that his boy Charles relished and reproduced ever after, affectionately quoting him almost to the last – ‘as my poor father would say …’ John seems not to have had an official job till 1807, when, at the relatively late age of nineteen, he had gone to work as an ‘extra’ clerk in the Navy Pay Office in Somerset House, off the Strand in London. Patronage was the usual route to civil service appointments, and it seems very likely that John Dickens’s had been arranged by no less a figure than the high-flying Treasurer to the Navy, John Crewe’s political associate George Canning, soon to be Foreign Secretary and then, briefly, Prime Minister. At any rate, the following year the now twenty-year-old ‘extra’ clerk was thought presentable enough to be chosen to accompany Sheridan’s wife on a coach-ride from Portsmouth to London – the ever-versatile dramatist, his theatrical career long behind him, then being Receiver of the Duchy of Cornwall. The fact that John was from Crewe Hall would have naturally encouraged the Sheridans’ confidence in him: The School for Scandal is dedicated to Mrs Crewe, whose housekeeper, John’s mother, Elizabeth, would have been well known to Mrs Sheridan. She was a formidable figure, this Elizabeth Dickens, with a lifetime of service in great houses; before her marriage, she had been Lady Blandford’s maid at Grosvenor House. She was responsible for the destinies of her large staff, answerable directly to Mr and Mrs Crewe; but off-duty, she had a particular gift for storytelling, and her employers’ children would seek her out in the housekeeper’s room, sitting spellbound at her feet as she spun her yarns. ‘Inimitable’ was the word that Lady Houghton, one of those children, used of Elizabeth Dickens a lifetime later: an adjective that would immortally attach itself to her grandson.

Meanwhile, her son John had fallen in love with Elizabeth Barrow, whose brother Thomas was his colleague; their father, Charles Barrow, was John’s superior in the Navy Pay Office, rejoicing in the magnificent title of Chief Conductor of Monies in Towns – or at least he did, until he was discovered conducting large sums of government monies into his own pocket, at which point he fled the country, later creeping back to the Isle of Man, where he ended his days. Dodgy money thus makes an appearance very early on in Dickens’s saga; money, in one form or another, always featured prominently and tiresomely in his life.

Charles Barrow was caught with his hand in the till in 1810, a year after John and Elizabeth had got married, in some style, at the Church of St Mary-le-Strand, just up the road from Somerset House, John’s head office. John was transferred to Portsmouth, where he and Elizabeth set up house. John Dickens’s Lady, like his mother, was a renowned storyteller, famous for the sharpness of her observation and the unerring accuracy of her ear: ‘on entering a room, she almost unconsciously took stock of its contents’, said a friend, ‘and if anything struck her as out of place or ridiculous, she would afterwards describe it in the quaintest manner.’ Not necessarily someone you would want to come visiting every day. ‘She possessed,’ her friend remembered, ‘an extraordinary sense of the ludicrous.’ She equally commanded a sense of the pathetic, effortlessly reducing her listeners to tears. Above all, she was noted for her vivacity. She liked to say that she had been dancing all night the day before Charles was born; diligent research has shown that the ball took place four days earlier, which only goes to show what a spoilsport diligent research can be. Whatever the timing, dancing all night when you’re nine months gone suggests a certain commitment to fun.

Charles was born in a small but pleasant newly built terraced house in Portsea, a suburban outgrowth of a wildly prosperous wartime Portsmouth that was bursting at the seams. In that famous year of 1812, the war with Napoleon was raging on land and at sea; just five years earlier the Battle of Trafalgar had triumphantly established that Britannia did, indeed, rule the waves, and there was a lot of work to be had building, equipping, and maintaining the Fleet. John’s job was solid and decently rewarded. Charles was the second child but the first boy, which may partly account for the exuberance of the newspaper announcement. The birth itself took place, as John Dickens’s proud announcement notes, on Friday, 7 February. Charles Dickens had occasion to observe that pretty well anything of importance that happened in his life thereafter, happened on that day of the week. The household into which he was born that particular Friday consisted of his mother and father, his two-year-old sister, Fanny, the sixteen-year-old housemaid, Mary Weller, whom we have already met as Charles’s first reviewer, and another, older, maid, Jane Bonny. Pleasant though the house and its surroundings were, there was no running water, which may have been what encouraged the family to move, four months after Charles was born, to a house in Hawke Street, which did have that precious commodity on tap, and was in a no less agreeable vicinity, with the added advantage of being minutes away from the Navy Pay Office.

John’s salary had been steadily rising to a very comfortable £230 per annum, so their next move, eighteen months later, was to leafy Southsea, in a roomy house with a nice little front garden; it represented a distinct step up the social ladder for them. There they were joined by the latest and newest young Dickens, Alfred, and Elizabeth’s much-loved sister, Mary, nicknamed Aunt Fanny, whose husband had died in action at sea. By now, the tide of the war had decisively turned for Napoleon, who was defeated and exiled in April 1814: good news for the world, but not for Portsmouth, and certainly not for John Dickens, who was called back to London in January 1815, thus losing his Outpost Allowance, and suffering a substantial reduction of salary to £200. It was the first major financial setback in a lifetime of increasing pecuniary embarrassment.

The family, now reduced in size after the loss of little Alfred from hydrocephalus (water on the brain), found its first London address in Norfolk Street, now Cleveland Street, just off the Marylebone Road in Fitzrovia – a good bustling area: it was within toddling distance of two great institutions, the Theatre of Variety and the workhouse. They were the alpha and omega of the young Charles Dickens’s life, heaven and hell in the same street. Just round the corner from Norfolk Street lived John’s mother, Elizabeth Dickens Sr, now retired from domestic service. Visits to her, according to Dickens’s lightly disguised accounts forty-five years later, were intimidating affairs, with none of the cosy under-stairs storytelling in which her employers’ children had so delighted. The ‘grim and unsympathetic old personage of the female gender, flavoured with musty dry lavender, dressed in black crape … with a fishy eye [and] an aquiline nose’ certainly held him spellbound, but the tales she span for him were of serial killers with missing ears and people slaughtered and turned into pies. Even getting a present from this ‘adamantine woman’ was an alarming event. On one occasion she took him to the World of Toys, shaking him on the way, from time to time, and insisting on wiping his nose herself ‘on the screw principle’. When they got to the bazaar, he was told to choose a present for half a crown; finally he settled on a Harlequin Wand. It proved to be a disappointment, however: it had no effect whatever on the rocking horse; it failed to produce a live clown out of the beefsteak pie at supper; and could not even influence the mind of his parents ‘to the extent of suggesting the decency and propriety of their giving me an invitation to sit up at dinner’. In time, he would amply make up for this first disappointing performance as a magician.

An even greater mystery was why his far from indulgent grandma had given him a present at all. For many years, he says, he was unable ‘to excogitate the reason’. At last he got it: ‘I have now no doubt she had done something bad in her youth, and that she took me out as an act of expiation.’

Charles was three at the beginning of his first metropolitan sojourn, and five when it ended. It seems that at some point during their time in Norfolk Street, John had been obliged to borrow money from his mother (in her will she mentions having given him advances); he must have been very glad, one way and another, to be transferred away from London to Sheerness in Kent, restored to his former salary, or rather better, a whopping £289 per annum.

In Sheerness it seems they lived in the racy Blue-town district, which had the immeasurable attraction of being the location of a thriving theatre; it is reported that the Dickenses’ house was so close to it that they could overhear the shows in their front room. The theatre was in Victory Street, and victory was very much in the air: performances habitually ended with rousing choruses of ‘Rule Britannia’ and ‘God Save the King’, which presumably echoed round their parlour. But the days of Sheerness’s theatre were numbered: it was pulled down to make way for an expansion of the dockyards, and, on the crest of this wave of expansion, John Dickens was transferred again, this time to Chatham, the ‘wickedest place in the world’, according to a fellow naval clerk. Wicked it may have been – as any self-respecting town with an itinerant population of soldiers and sailors was in honour bound to be – but it was the scene of incomparably the happiest days of Charles Dickens’s life. Here he lived for five years, between the ages of five and ten; here he immersed himself in nature; here he learned first his alphabet, then the rudiments of English and Latin, at his mother’s knee; here he had his first – very nearly his only – formal education, initially at a Dame’s school, and then at the hands of the local Nonconformist Minister’s highly qualified son, William Giles, freshly down from Oxford. From here he was taken to see his first plays; here he discovered the Aladdin’s Cave of his father’s modest library; here he and his sister sang their little songs, shepherded by their father, at the Mitre Hotel, which was run by family friends; here he was admired and approved of, encouraged and rewarded; here he was loved; here his inner life was everywhere richly nourished, and the matrix of his imagination set.

He was, at first, a sickly child, subject to spasms and incapable of active exertions; a lucky circumstance, he always said, because it pushed him to read while his contemporaries were throwing themselves around the sports field. While they ran about, he sat there, on his bed, he said, reading, ‘as if for life’. ‘Oh, he was a terrible boy to read,’ said Mary Weller. The books in his father’s little library were the great picaresque English novels of the eighteenth century – Roderick Random, Peregrine Pickle, Humphrey Clinker, Tom Jones – with their witty, thrustful, middle-class heroes outwitting a gallery of rogues and rivals; Robinson Crusoe and Don Quixote (not ALL of Don Quixote, surely?); and Gil Blas (Smollett à la française). There were collections of essays from Joseph Addison’s great eighteenth-century magazines, The Tatler and The Spectator; and then there were two books of immeasurable delight which entered deep into his imagination: The Arabian Nights and the Collected Farces of the eighteenth-century actress and playwright, Elizabeth Inchbald (these last read over and over again). All rather grown-up stuff, some of it quite risqué, but ‘whatever harm was in some of them, was not there for me; I knew nothing of it.’

His visits to the theatre, the little Theatre Royal at Rochester, were undertaken under the aegis of a young lodger, James Lamert – the son of Aunt Fanny’s new husband – who had taken warmly to the bright, odd, intense little boy. These excursions brought to living, breathing reality the visions he had already encountered between the covers of his books. He was wildly excited by what he saw; the world of the theatre, its mysteries and its absurdities had seized him by the throat:

Many wondrous secrets of Nature did I come to the knowledge of in that sanctuary: of which not the least terrific were, that the witches in Macbeth bore an awful resemblance to the Thane and other proper inhabitants of Scotland; and that the good King Duncan couldn’t rest in his grave, but was constantly coming out of it and calling himself somebody else.

Once home, he demanded that the kitchen be cleared so that he and the little boy next door could act out scenes from the plays they’d just seen; he then sat down and knocked off Misnar, Sultan of India: A Tragedy, his literary début, as far as we know; after its short run in the kitchen in Chatham, it disappeared. Later, on two consecutive Christmases, he was taken up to London to see the greatest clown of the age, Joey Grimaldi. Best of all was the invitation to sit in on rehearsals of the amateur productions staged by his friend Lamert: the making of theatre became a passion for the eight-year-old boy, a passion that would endure till very nearly the day he died.

The house into which the Dickenses moved when they first went to Chatham was at 2 Ordnance Terrace; it was commodious – on three floors – but only just big enough to hold the now swarming family, to which over the next two years were added three more children, Letitia, Harriet and Frederick, joining Fanny and Charles, Elizabeth and John, as well as the two servants and Aunt Fanny. The house commanded ‘beautiful’ views across the surrounding countryside, promised the auction announcement, taking in the river, and, just beyond, the noble fourteenth-century spire of Rochester Cathedral; it had its own garden and yard. It was, the announcement proclaimed, ‘fit for a genteel family’, which is how Charles and the rest of the family never ceased to think of themselves, whatever adverse circumstances life might throw up.

Some of those circumstances – brought about by a combination of his father’s fecklessness and the peculiar salary structure of employees of the Naval Pay Office – caused them to move, in May 1821, when Charles was nine. The new house, at St Mary’s Place, was known as The Brook; it was a little smaller, and there was no beautiful view any more; but he was so utterly caught up with his imaginative life that the loss of a room here or a view there would scarcely have registered with him. Certainly he would have known nothing of his father’s inexorable accumulation of debt. Most often he was to be found in the room where his father’s books were kept, either reading them for the twentieth time, or acting out scenes from them; or else he was at school, eagerly absorbing whatever Mr Giles could tell him; or he was out playing with his friends. He was sturdier now, happily giving himself over to the games he had quickly mastered. The town offered constant diversions: he keenly watched ‘the gay bright regiments always going and coming, the continual paradings, the successions of sham-sieges and sham-defences.’ In Rochester, he was held up high by his mother to catch a glimpse of the Prince Regent on a tour of inspection; every St Clement’s Day he saw the saint’s pageant, with Old Clem chaired through the streets by local men in lurid masks. As a special privileged treat, he would go up and down the Medway in naval vessels with his father; together they took epic walks across the fields all the way over to Rochester and back. Near the village of Higham they came upon a house that fascinated little Charles. It was called Gad’s Hill Place. And he told his father that one day he would like to live there; and his father promised him that if he worked very very VERY hard, he would.

And so it came to pass. But not before our hero had undergone many, many trials, to the first of which he was about to submit.

It’s worth stopping for a moment to look at the ten-year-old Charles Dickens. He was vivacious, imaginative, amusing, dreamy, affectionate, at times a little over-emotional; he read a great deal, he loved the theatre and dressing up and playing games; as a pupil he was eager and apt; he was good-looking, polite and charming, confident in the love both of his parents and of his siblings, of his extended family and his many friends. He was the crown prince of his little kingdom. He can have had nothing but optimism for the future. In all of these things, he was like many, many children who go on to live perfectly ordinary lives. What happened to him next all but destroyed his life, but it turned him into Charles Dickens. Had he not been the ten-year-old that he was, with that strong base of love and confidence and approval, it would surely have finished him off.

TWO

Paradise Lost

John Dickens was summoned back to Navy Pay Office headquarters at Somerset House in June 1822, not a moment too soon; despite the improvement in his salary, his alarmingly mounting debts were becoming difficult to deal with. He sold up the family’s effects at The Brook, such as they were, and they headed west, finding accommodation in Camden Town in the north of London, near King’s Cross. Charles was not with the family: his schoolmaster, William Giles, had asked for him to be allowed to stay behind to finish his final term of work; which he duly did, lodging with Giles. At some point in the autumn he made his own way to London. It was not an encouraging start:

As I left Chatham in the days when there were no railroads in the land, I left it in a stage-coach. Through all the years that have since passed, have I ever lost the smell of the damp straw in which I was packed – like game – and forwarded, carriage paid, to the Cross Keys, Wood Street, Cheapside, London? There was no other inside passenger, and I consumed my sandwiches in solitude and dreariness … and I thought life sloppier than I had expected to find it.

His arrival at Camden Town in the north of London only confirmed this perception. ‘A little back-garret’, he called his room. In fact, No. 16 Bayham Street was a relatively new dwelling, part of a development scheme completed ten years earlier, not unlike the houses they had occupied in Chatham; all the other houses were occupied by professionals of one sort or another – an engraver, a retired linen draper, a retired diamond merchant, and so on. There were fields behind the houses where in summer hay was still made. The area was semi-rustic, the houses having been built on part of the former gardens of the Mother Red Cap tavern, an old highwayman’s inn. It was, in fact, village-like.

But to the boy, after populous, bustling Chatham, the street must have seemed bleak and woebegone: ‘as shabby, dingy, damp, and mean a neighbourhood as one would desire not to see,’ he wrote, thirty years later. ‘Its poverty was not of the demonstrative order. It shut the street doors, pulled down the blinds, screened the parlour windows with the wretchedest plants in pots, and made a desperate stand to keep up appearances.’ As with the council estates of the 1950s, the price of amenities was the loss of community. The easy openness of Chatham seemed far way: this was the heartless Metropolis. In his former existence, misfortune had been handled discreetly – he himself had known nothing about his father’s troubles – but here

to be sold up was nothing particular. The whole neighbourhood felt itself liable, at any time, to that common casualty of life. A man used to come into the neighbourhood regularly, delivering the summonses for rates and taxes as if they were circulars. We never paid anything until the last extremity and Heaven knows how we paid it then.

Any possible sense of gentility had disappeared. There were, he said, no visitors ‘but Stabber’s Band, the occasional conjuror and strong man; no costermongers.’ There were a few shabby shops – a tobacconist, a weekly paper shop. And at the corner, a pub. ‘We used to run to the doors and windows to look at a cab, it was such a rare sight.’

This isolated little outpost was no more than thirty minutes’ walk from his old lodgings in bustling Norfolk Street in Marylebone, but to the ten-year-old boy, it evidently felt like some kind of abandoned urban village. London was in the process of expanding, and Camden was one of the points on the pioneer trail. It was not a slum; not at all. But it lacked roots, identity, humanity. No. 16 itself, with only four rooms, was horribly cramped. There were six children and their two parents, plus a servant girl they had brought with them from the workhouse in Chatham, and James Lamert. Charles had nowhere to go and nothing to do. There were no more agreeable visits to the Mitre to be held up for admiration; he knew no one of his own age with whom to dress up and put on a play; and above all, he had no schooling, which he missed bitterly. His appetite for learning had grown and grown in Chatham. His so obviously not attending school proclaimed the family’s poverty to the world; his pride was stung. John Dickens seemed, he said, ‘to have utterly lost at this time the idea of educating me’. For want of anything to do, he was reduced to cleaning his father’s boots and running ‘such poor errands as arose out of our poor way of living’. His only diversion was the toy theatre that his friend James had built for him: he spent hours and hours intensely absorbed in it. It was, Lamert said, ‘the only fanciful reality in his present life’. John Dickens was naturally distracted by his financial situation: with the loss of the Outpost Allowance, his salary had declined from £400 to £350; and new debts were mounting. He had not paid the rates, and had been running up bills with the local tradesmen. And yet somehow they managed to find the thirty-eight guineas a year for twelve-year-old Fanny, whose musical gifts had gained her a place at the Royal Academy of Music, to board from April of 1823. Charles loved his sister deeply, but this must have been a slap in the face to him: to see such thought, care and money lavished on her while his needs were entirely ignored acutely enhanced his sense of abandonment.

The speed with which everything that had made life good had disappeared was shocking enough. John was clearly powerless to do anything about it; and Charles’s mother – sharp, witty, vivacious Elizabeth – was perhaps not the person to turn to for comfort; besides, she had her hands full. This was the beginning of a very swift growing up for the boy, the start of a premature assumption of responsibility for his own life that was to be the making of him. Or at least, of ‘Charles Dickens’.

As a distraction, he was packed off to his mother’s brother, Uncle Thomas, who lived over a bookseller’s in Soho, about forty-five minutes away; the bookseller’s wife let the book-hungry boy loose in the shop for hours at a time. More ambitiously, the eleven-year-old boy walked the seven miles to the house of his godfather Christopher Huffam, a certified naval rigger, in Limehouse, in Dockland. Huffam and his friends encouraged Charles to perform his repertory of comic songs for them, which cheered him up no end – an audience again at last. One of Huffam’s chums declared the boy ‘a progidy’. He then walked the seven miles back home to Camden. Here in the vast metropolis he began his life-long career as a walker, pounding the streets of London, looking at nothing, he said, but seeing everything. Early in 1823, not long after the Dickenses had returned to London, he was taken to see the Church of St Giles-in-the-Fields with its notorious attendant slums, which would in time become one of his favourite haunts. On this occasion, he somehow got detached from the adult responsible for him, and wandered aimlessly across the whole of London, eking out the one-and-fourpence in his pocket. He told himself that he was Dick Whittington and would soon be called upon to be Lord Mayor of London, then changed plan, determining instead to enlist in the army as a drummer boy. He ate a pie here and a bun there, then as darkness fell, he spent sixpence on a visit to the theatre, where for a few hours he managed to forget himself and his woes. Finally, when night had fallen, he admitted the truth to himself, and ran round crying out to whoever would listen, ‘O, I am lost! I am lost!’ until a watchman in a box took pity on him and somehow got a message to John Dickens, who retrieved the boy, now fast asleep.

As recounted by Dickens thirty years later in an essay he called ‘Gone Astray’, the story has a whimsical charm, but the reality of a particularly tiny, not especially healthy, eleven-year-old wandering alone and untrammelled across the dangerous, desperate city would have been at least as alarming in 1823 as it is in 2012; but the young Charles was rapidly discovering uncommon resources within himself. He had to. ‘I fell into a state of dire neglect, which I have never been able to look back upon without a kind of agony.’ His anguish was the least of his parents’ worries.

With financial ruin looming more threateningly each day, Elizabeth, determined to, as she said, ‘do something’, had an inspiration: they would open a school. Of course! They would be rich! Mrs Dickens’s Establishment, they would call it. They would need to find premises, of course, which they duly did in a brand new and rather splendid development at the top end of Gower Street, parallel to the Tottenham Court Road. Brushing the dust of Bayham Street off their feet, they moved into magnificent new accommodation at No. 4 Gower Street North at Christmas, 1823. They screwed the brass plate on the door and settled back for the queues of eager students to start forming. Charles was deputed to stuff circulars through the local letter boxes. Inexplicably, ‘nobody ever came to the school, nor do I recollect that anybody ever proposed to come, or that the least preparation was made to receive anybody.’ This insane last gamble delivered the final coup de grâce to the Dickenses’ fragile finances.

It was at this point that Charles’s life changed irrevocably. What followed was so painful for him to contemplate that he never spoke of it to anyone whatsoever, until in March of 1847 – when he was thirty-five and already a national figure, universally admired as the author of The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, The Old Curiosity Shop, Martin Chuzzlewit, and A Christmas Carol – his close friend John Forster casually recounted to Dickens a conversation he had had with a former acquaintance of Dickens’s father. The man had mentioned that Charles had been employed as a boy in a warehouse off the Strand. Was there anything in it, Forster wondered. Dickens fell very silent, and a few days later sent his astonished friend – swearing him to strictest secrecy – a lengthy letter in which he detailed, in language of meticulous precision and iron control, a chapter of events in his early life that had branded him for ever.