скачать книгу бесплатно

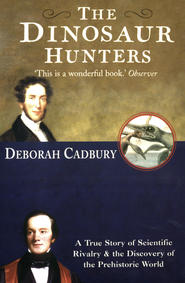

The Dinosaur Hunters: A True Story of Scientific Rivalry and the Discovery of the Prehistoric World

Deborah Cadbury

The story of two nineteenth-century scientists who revealed one of the most significant and exciting events in the natural history of this planet: the existence of dinosaurs.In ‘The Dinosaur Hunters’ Deborah Cadbury brilliantly recreates the remarkable story of the bitter rivalry between two men: Gideon Mantell uncovered giant bones in a Sussex quarry, became obsessed with the lost world of the reptiles and was driven to despair. Richard Owen, a brilliant anatomist, gave the extinct creatures their name and secured for himself unrivalled international acclaim.Note that it has not been possible to include the same picture content that appeared in the original print version.

THE

DINOSAUR

HUNTERS

A Story of Scientific RivalryAnd the Discovery of thePrehistoric World

Deborah Cadbury

Dedication (#ulink_c38b93a1-9f5b-5e2f-8227-37bb7a07b0bb)

For my mother and Martin,

the first readers,

with love

Contents

Cover (#u24d241e1-ace7-5b2c-813d-9ee0a93338bd)

Title Page (#ucaba3139-00d1-547f-ae6c-9c4749c24ee6)

Dedication (#uc9ff41f7-e639-55dc-8e30-4db1a792a832)

PART ONE (#uc1394390-7631-52ca-8401-e17b30d4a37c)

1 An Ocean Turned to Stone (#u3f847bda-22eb-58ec-a471-5bdba931ffa7)

2 The World in a Pebble (#u26e1ac8e-0378-5be0-b4c8-86c141a7ab54)

3 Toast of Mice and Crocodiles for Tea (#u14c18132-8219-5e5f-a6a5-d468f37891d4)

4 The Subterranean Forest (#u99c736fe-3464-51b3-a89f-7ef7b9f03560)

5 The Giant Saurians (#litres_trial_promo)

PART TWO (#litres_trial_promo)

6 The Young Contender (#litres_trial_promo)

7 Satan’s Creatures (#litres_trial_promo)

8 The Geological Age of Reptiles (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Nature, Red in Tooth and Claw (#litres_trial_promo)

10 Nil Desperandum (#litres_trial_promo)

PART THREE (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Dinosauria (#litres_trial_promo)

12 The Arch-hater (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Dinomania (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Nature without God? (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes and Sources (#litres_trial_promo)

Select Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Works (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PART ONE (#ulink_90148cae-b323-515b-875a-8d860d9cc3d2)

1 An Ocean Turned to Stone (#ulink_30a3bf17-c06d-50a0-8281-25d1375e97f8)

She sells sea-shells on the sea-shore,

The shells she sells are sea-shells, I’m sure

For if she sells sea-shells on the sea-shore

Then I’m sure she sells sea-shore shells.

Tongue-twister by Terry Sullivan, 1908,

associated with Mary Anning

On the south coast of England at Lyme Regis in Dorset, the cliffs tower over the surrounding landscape. The town hugs the coast under the lee of a hill that protects it from the south-westerly wind. To the west, the harbour is sheltered by the Cobb, a long, curling sea wall stretching out into the English Channel – the waves breaking ceaselessly along its perimeter. To the east, the boundary of the local graveyard clings to the disintegrating Church Cliffs, with lichen-covered gravestones jutting out to the sky at awkward angles. Beyond this runs the dark, forbidding crag face of Black Ven, damp from sea spray. The landscape then levels off across extensive sweeps of country, to where the cliffs dip to the town of Charmouth, before rising sharply again to form the great heights of Golden Cap.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, according to local folklore, the stones on Lyme Bay were considered so distinctive that smugglers running ashore on ‘blind’ nights knew their whereabouts just from a handful of pebbles. However, it was not only smugglers and pirates who became familiar with the peculiarities of these famous cliffs. Through a series of coincidences and discoveries Lyme Bay soon became known as one of the main areas for fossil hunting. Locked in the layers of shale and limestone known as the ‘blue lias’ were the secrets of a vast, ancient ocean now turned to stone, the first clue to an unknown world.

In 1792, war erupted in Europe and it became dangerous for the English gentry to travel on the Continent. Many of the well-to-do classes adopted the resorts of the south coast of England. The dramatic scenery around Lyme Bay became a favourite among those who spent part of the season at Bath. In the summer, smart carriages often lined the Parade and the steep, narrow streets that nestled into the hillside. The novelist Jane Austen was among those who visited early in the nineteenth century. She was charmed by the High Street, ‘almost hurrying into the sea’, and ‘the very beautiful line of cliffs stretching out to the east’. The Cobb curving around the harbour became the dramatic setting for scenes in her new novel Persuasion. It was here that Louisa Musgrove fell ‘lifeless … her eyes closed, her face like death’, and was nursed back to health by the romantic sea captain.

Jane Austen’s letters to her sister, Cassandra, reveal that during her short stay she met an artisan in the town by the name of Richard Anning. He was summoned to value the broken lid of a box and, according to Jane Austen, was a sharp dealer. She told her sister that Anning’s estimate, at five shillings, was ‘beyond the value of all the furniture in the room together’.

Richard Anning, even as a skilled carpenter, struggled to make a living. The blockade of European ports during the Napoleonic Wars had caused severe food shortages. With no European corn available, the price of wheat had risen sharply, from 43 shillings a quarter in 1792 just before the war, to 126 shillings in 1812. Since bread and cheese was the staple diet for many in the southern counties, the spiralling price of a loaf caused great suffering. Wages did not rise during this period, and in many districts workers received a supplement from the parish to enable them to buy bread. Industrious labourers effectively became paupers relying on parish charity, and there was a real fear of starvation. While the gentry, glimpsed beyond sweeping parklands in their country estates, benefited from high prices and seemed impervious to the effects of war, the poor began to riot. The flaming rick or barn became a symbol of the times. Richard Anning was himself a ringleader of one protest over food shortages.

In rural Dorset, the poor were not only hungry, but with a shortage of fuel they also faced damp, cold conditions and sometimes worse. Richard Anning and his wife, Molly, lived in a cottage in a curious array of houses built on a bridge over the mouth of the River Lym. On one occasion, they awoke to find that ‘the ground floor of their home had been washed away during the night’. Their modest home had succumbed to an ‘exceptionally rough sea which had worked the havoc’.

The desire to keep warm could have lain behind a tragedy that befell the Annings’ eldest child, Mary, at Christmas in 1798. The event was reported starkly in the Bath Chronicle: ‘A child, four years of age, of Mr R. Anning, a cabinet maker of Lyme, was left by the mother about five minutes … in a room where there were some shavings by a fire … The girl’s clothes caught fire and she was so dreadfully burnt as to cause her death.’ Whether Mary was huddling too close to the flames for warmth, or accidentally stumbled, is not known. It is known, however, that her distraught mother, on the birth of their next daughter six months later, called her Mary in memory of her dead sister.

Naming a newborn after a child that had died was a common practice at a time when a quarter of poor infants died in their first year and half were dead before the age of five. Many were undernourished and readily succumbed to consumption, pneumonia, smallpox, measles or other diseases. Apart from the sudden death of their eldest daughter Mary, the Annings had already lost two other children, Martha and Henry, by the year 1800. But fate was to intervene in an unexpected way in the young life of the second Mary Anning.

That summer, when Mary was just one year old, news reached Lyme Regis that a touring company of riders was to perform near the town. Among the enticements were a display of vaulting, riding stunts and a lottery, with prizes such as copper tea-kettles and legs of mutton. The arrival of the travelling performers was a welcome distraction for the local inhabitants, and crowds of people trekked past the church and the gaol near the Annings’ house to the equestrian show, set in a field on the outskirts of town. Mary was taken along in the care of a local nurse, Mrs Elizabeth Hasking.

By late afternoon a heavy thunderstorm developed, but the crowds would not disperse, perhaps lingering to see who had won the lottery. Then, in the words of the local schoolmaster, George Roberts: ‘a vivid discharge of electric fluid ensued, followed by the most awful clap of thunder that any present ever remembered hearing, which re-echoed around the fine cliffs of Lyme Bay. All appeared deafened by the crash. After a momentary pause a man gave the alarm by pointing to a group that lay motionless under a tree.’

There were three dead women, among them Mary’s nurse, Elizabeth, whose hair, arm and cap along the right side were ‘much burnt and the flesh wounded’. She was still holding the baby, who was insensible and could not be roused. The second Mary Anning, known to be ‘dear to her parents’, was carried back to Lyme, ‘in appearance dead’. But when bathed in hot water, gradually she was revived, to the ‘joyful exclamations of the assembled crowd’. According to the family, this was a turning-point for the young Mary Anning: ‘She had been a dull child before but after this accident she became lively and intelligent.’

As Mary grew older, she took a keen interest in helping her father gather fossil ‘curios’ from the beach to sell to tourists. In the early part of the century, Richard Anning had several more children to support: the boys Joseph, Henry, Percival and Richard and another daughter, Elizabeth. To supplement his meagre income as a carpenter, Mary and her father set up a curiosity table outside their home to sell their wares to the tourists. However, selling fossils was a competitive business.

One collector, called the ‘Curi-man’ or Captain Cury and known locally as a ‘confounded rogue’, would intercept the coaches and sell specimens to travellers on the Exeter to London turnpike. Another ill-fated collector was Mr Cruikshanks, who could often be seen along the shoreline with a long pole like a garden hoe. When Cruikshanks lost the small stipend supporting him, leaving nothing but a tiny income from the sale of curios, he closed the account of his miserable existence and committed suicide by leaping off the Gun-Cliff wall in the centre of Lyme into the sea.

No one could explain what these ‘curios’ were. Petrified in the rocks on the shore were strange shapes, like fragments of the backbone of a giant, unknown creature. These were sold locally as ‘verteberries’. There were enormous pointed teeth, thought to be derived from alligators or crocodiles. Relics of ‘crocodilian snouts’ had been reported in the region for several years. There were also pretty fossil shells and stones, called ‘John Dory’s bones’ or ‘ladies’ fingers’.

At the time, throughout England, superstitions abounded about the meaning of fossils. The beautiful ammonites, called ‘cornemonius’ in the local dialect, with their elegant whorls like the coils of a curled-up serpent, were also known as ‘snake-stones’. The subject of the wildest speculation, such stones were thought in earlier centuries to have magical powers, and could even serve as an oracle. The ammonite, it was believed, could bring ‘protection against serpents and be a cure for blindness, impotence and barrenness’. Occasionally a snake’s head would be painted on the coils to be used as a charm. But snake-stones were not always a symbol of good fortune. In some regions it was thought that they were originally people, who for their crimes were first turned into snakes and then cast into stone. By divine retribution anyone who was evil could be turned to dust, just as Lot’s wife had been turned into a pillar of salt.

There were other strange curios, too, such as the long, pointed belemnites. These were said to be thunderbolts used by God, known colloquially as ‘devil’s fingers’ or ‘St Peter’s fingers’. These also had special powers. According to ancient tradition powdered belemnites could cure infections in horses’ eyes, and water in which belemnites had been dipped was even thought to cure horses of worms.

The fossils that resembled fragments of real creatures like snakes or crocodiles defied explanation. Myths of the time give tantalising insights. Some held that they were the ‘seed’ or ‘spirit’ of an animal, spontaneously generated deep within the earth, which would then grow in the stone. According to others, fossils were God’s interior ‘ornament’ of the earth, just as flowers were the exterior ornament. They might even have been planted by God as a test of faith! After all, if they were the remains of real animals that had once thrived, how had they burrowed their way down so deep into the rocks? And why would any creature do this? Alternatively, if the rocks had formed gradually around them, long after the animals had perished, this implied that God’s Creation had occurred over a period of time, not in a few days as described in Genesis. Entombed in the stony cliff-face was a mystery beyond explanation.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century many had absolute faith in the word of the Bible. To them, the most convincing explanation was that these were the remains of creatures that had died during Noah’s Flood and had been buried as the earth’s crust re-formed. Although there are no records of Mary Anning’s view as a child, it seems likely that this was the framework of colourful folklore and unyielding religious belief that informed her searches along the cliffs of Lyme Bay.

Mary became skilled at searching for ‘crocodiles’. Laid out on the table before their house were giant bones of ‘Crocodiles’, ‘Angels’ Wings’, ‘Cupid’s Wings’, ‘Verteberries’, and ‘Cornemonius’. Her searches on the beach made her mother Molly Anning very angry, as, according to Roberts the schoolmaster, ‘she considered the pursuit utterly ridiculous’. It was also dangerous. Rainwater endlessly percolating through layers of soft shales and clays caused frequent mudslides and rockfalls, especially in winter. There was also the risk of being caught by the sea as the fossils, revealed by erosion, had to be removed before the tide turned and the waves washed them away. Sometimes Mary and her father were trapped by the rising waves between the sea and the cliffs, and had to struggle up the slippery rockface to safety. On one occasion, Richard Anning was caught in a landslide as part of the Church Cliffs collapsed into the sea, and narrowly escaped being carried down with the rocks and crushed on the beach below.

One night in 1810, however, Anning was not so lucky when, taking a short cut to Charmouth, he strayed from the path and fell over the treacherous cliffs at Black Ven. He was severely weakened by his injuries and soon succumbed to the endemic consumption and died. Molly and the children were destitute. They had no savings; indeed, Richard Anning had left his family with £120 worth of debt, a large sum at a time when the average labourer’s wage was around 10 shillings a week. There was no way that Molly could readily pay back such a debt. As a result, she was obliged to face the humiliating prospect of appealing for help from the Overseers of the Parish Poor. It was a considerable misfortune for an artisan family.

Under the old Poor Laws dating from Tudor times, the poverty-stricken could be accommodated in one of fifteen thousand Poor Houses in England, where inmates struggled with conditions recognisable from the pages of Charles Dickens. Alternatively the poor received ‘outdoor poor relief’, as in the case of the Annings, which enabled them to stay in their own home while receiving a supplement from the parish. Although conditions on outdoor relief varied across districts, it was usually a miserly amount for food and clothing, or sometimes given in kind as bread and potatoes. The average weekly payment on outdoor poor relief was three shillings at a time when the minimum needed to scrape a living was six or seven shillings a week. Paupers were thus dependent on charity or could appeal to relatives for support. Older children were expected to help out with any number of tasks – horse holding, running as messengers, and cleaning or other domestic work. It was common for those on poor relief to be severely malnourished, and the hardships the Anning family endured were so severe that of all the children, only Mary and Joseph were to survive.

While Joseph, Mary’s elder brother, was apprenticed to an upholsterer, Mary continued to search the beach for fossils. One day she found a beautiful ammonite, or snake-stone. As she carried her trophy from the beach a lady in the street offered to buy it for half a crown. For Mary this was wealth indeed, enough to buy some bread, meat and possibly tea and sugar for a week. From that moment she ‘fully determined to go down upon the beach again’.

During 1811 – the exact date is not known – Joseph made a remarkable discovery while he was walking along the beach. Buried in the shore below Black Ven, a strange shape caught his eye. As he unearthed the sand and shale, the giant head of a fossilised creature slowly appeared, four feet long, the jaws filled with sharp interlocking teeth, the eye sockets huge like saucers. On one side of the head the bony eye was entire, staring out at him from some unknown past. The other eye was damaged, deeply embedded in the broken bones of the skull. Joseph immediately hired the help of two men to assist him and uncovered what was thought to be the head of a very large crocodile.

Joseph showed Mary where he had found the enormous skull, but since that section of the beach was covered by a mudslide for many months afterwards it was difficult to look for more relics of the creature. Nearly a year elapsed before Mary, who was still scarcely more than twelve or thirteen, came across a fragment of fossil buried nearly two feet deep on the shore, a short distance from where Joseph had found the head.

Working with her hammer around the rock, she found large vertebrae, up to three inches wide. As she uncovered more, it was possible to glimpse ribs buried in the limestone, several still connected to the vertebrae. She gathered some men to help her extract the fossils from the shore. Gradually, they revealed an entire backbone, made up of sixty vertebrae. On one side, the shape of the skeleton could be clearly seen; it was not unlike a huge fish with a long tail. On the other side, the ribs were ‘forced down upon the vertebrae and squeezed into a mass’ so that the shape was harder to discern. As the fantastic creature emerged from its ancient tomb they could see this had been a giant animal, up to seventeen feet long.

News spread fast through the town that Mary Anning had made a tremendous discovery: an entire connected skeleton. The local lord of the manor, Henry Hoste Henley, bought it from her for £23: enough to feed the family for well over six months.

The strange creature was first publicly displayed in Bullock’s Museum in Piccadilly in the heart of London. It quite baffled the scholars who came to visit, as there was no scientific context in England within which they could readily make sense of the giant fossil bones. Geology was in its infancy and palaeontology did not exist. The peculiar ‘crocodile’, with its jaw set in a disconcerting smile and its enormous bony eyes, was something inexplicable from the primeval world. In the words of a report in Charles Dickens’s journal, All the Year Round, there was to be a ‘ten year siege before the monster finally surrendered’ and revealed its long-buried secrets to the gentlemen of science. Nearly a decade was to elapse before the experts could even agree on a name for the ancient creature.

As news of Mary Anning’s discovery reached scholarly circles in London and beyond, one of the first to visit her at Lyme Regis was William Buckland, a Fellow of the prestigious Corpus Christi College at Oxford University. Engravings of William Buckland portray a serious man, with even features and a broad expanse of forehead. Invariably, in these period poses, he is holding some fossil and formally attired in sombre black academic robes, looking the epitome of the nineteenth-century scientist. To those who knew him, he was renowned for qualities other than this stern and imposing image.

‘Dr Buckland’s wonderful conversational powers were as incommunicable as the bouquet of a bottle of champagne,’ wrote Storey Maskelyne, one of his Oxford colleagues. ‘It was at the feast of reason and the flow of social and intellectual intercourse that Buckland shone. A merrier man within the limit of becoming mirth I never spent an hour’s talk withal. Nothing came amiss with him from the creation of the world, to the latest news in town … In build, look and manner he was a thorough English gentleman, and was appreciated within every circle.’

Although Buckland had a wide range of interests his greatest passion was for ‘undergroundology’, as he called the new subject of geology. Many of his holidays from Oxford were spent at Lyme, where he explored the cliffs ‘with that geological celebrity, Mary Anning, in whose company he was to be seen wading up to his knees in the sea, searching for fossils in the blue lias’. At his lodgings by the sea, Buckland’s breakfast table was ‘loaded with beefsteaks and Belemnites, tea and Terebratula, muffins and Madrepores, toast and Trilobites, every table and chair as well as the floor occupied with fossils and rocks, earth, clays and heaps of books, his breakfast hour being the only time that the collectors could be sure of finding him, to bring their contributions and receive their pay’.

Born in the village of Axminster six miles inland from the Dorset coast, Buckland was no stranger to the impressive cliffs at Lyme. Since his childhood, the rocks of this region had enchanted him. ‘They were my geological school,’ he wrote, ‘they stared me in the face, they wooed me and caressed me, saying at every turn, Pray, Pray, be a geologist!’ His father, the Reverend Charles Buckland, had encouraged his enquiring approach to natural history. Following an accident, Charles Buckland was blind for the last twenty years of his life, but together father and son had explored the local quarries, the young William describing every detail of the beautiful fossil shells that his father could only touch. The boy’s exceptional ‘talent and industry’ were noted by his uncle, a Fellow at Oxford University, who steered William’s education, first to Winchester and then on to Corpus Christi College.

When William Buckland descended from his carriage in the city of famous spires at the turn of the nineteenth century, he had soon found that the university was steeped in an Anglican tradition in which the Scriptures, for many, were the key to understanding our history, and fossils were interpreted in this context. Most of the college lecturers took Holy Orders and advancement was principally through the Anglican Church. Buckland was himself ordained in 1809 and elected a Fellow in the same year.

At the time, more than a hundred years before radiometric dating was to dispel any lingering doubts about the vast antiquity of the globe, it was impossible to prove with certainty its exact age. For over two centuries, leading scholars had tried to solve this puzzle by taking the Bible as evidence. Studies of the earth were carried out by classicists, who could analyse sacred writings in Hebrew, Latin or Greek. In 1650 the Archbishop of Armagh, James Ussher, had concluded that God created the earth the night preceding Sunday 23 October, 4,004 years before the birth of Christ. His calculation had been made by adding together the life spans of the descendants of Adam, combined with knowledge of the Hebrew calendar and other biblical records. His dating of the earth, far from being ridiculed, was accepted as an excellent piece of historical scholarship, and following his lead, the study of chronology using sacred texts became an established approach for the next two hundred years.

Other methods of dating the earth were occasionally put forward. In 1715, Edmond Halley had proposed an ingenious experiment to the Royal Society in which the rate of increase in the saltiness of lakes and oceans could be calculated, assuming that they contained no salt when the globe was created. However, his ideas were not pursued, and Halley himself thought his results were likely to confirm ‘the evidence of the Sacred Writ, [that] Mankind has dwelt about 6,000 Years’.

Apart from revealing the age of the earth, the Bible had other geological implications that were to prove equally challenging for the early geologists like William Buckland. The prophet Moses outlined the story of Creation in which God made the Heavens, the Earth and every living thing in just seven days. In the biblical Creation story all creatures were made simultaneously. There is no prehistory in the Bible, and no prehistoric animals.

Moses also described a universal Flood in which ‘all the fountains of the great deep and the windows of heaven were opened’, and the entire face of the earth was wiped out, destroying all creatures except the few saved in Noah’s Ark. Sacred texts were scrutinised so as to shed more light on these events. One highly respected seventeenth-century naturalist, a German Jesuit, Athanasius Kircher, produced a detailed paper on the dimensions of the Ark and its animal contents. This approach was still flourishing in 1815, when the Reverend Stephen Weston studied changing place-names in Hebrew and Greek and claimed to locate the very site where Noah’s Ark came to land – on one of the highest mountains of the earth in Tibet.

At Oxford, William Buckland knew that anomalies unearthed in the rocks during the eighteenth century had challenged religious scholarship. Many stones resembling creatures or plants had been uncovered in locations that defied explanation. How could it be that sea shells were found on the peaks of the highest mountains? Was this evidence for the Flood and, if so, how had such vast amounts of water been suddenly generated and then fallen away? Savants were hard-pressed to explain why stones that looked just like animal teeth were found deeply embedded in solid rock, or how plants had become petrified within layers of coal. If fossils were the remains of animals, why were bones of tropical animals found in cold northern regions? Had the climate been mysteriously inverted? Stranger still, why was it that fossils resembling fish buried in one rock could be covered by layers of rock that contained only land animals, and in turn have shells and sea plants in the rocks above? This seemed to provide evidence of astonishing disorder and devastation, which was hard to understand if the world was purposefully designed in seven days by the Almighty Creator.

By the late eighteenth century scholars were making progress in understanding the history of the earth, not by taking the Bible as evidence, but the rocks themselves. One of the spurs for this was the growth of the mining industry in parts of Northern Europe such as Thuringia and Saxony. It was here on the present border between Germany and Poland that a pioneering thinker, Abraham Werner, created an order out of the seemingly haphazard formation of rocks beneath the earth’s surface.

Abraham Werner was taken out of school at Bunzlau when his mother died, and sent to work for his father who managed the local ironworks for the Duke of Solm. He later entered the great Mining Academy of Freiberg, where his teaching on mineralogy became famous throughout Europe. Werner’s ideas and others’ showed that the earth’s crust could be classified into four distinct categories of rock, which were always found to be in the same order of succession. The oldest of these were the crystalline rocks such as granite, gneiss and schist, containing no fossils. These became known as the Primary rocks, corresponding to the most primitive period of the earth’s history, since these rocks were laid down first in the earth’s crust. Above these in order of succession were the Transition rocks, including greywackes, slates and limestone. Only a small number of fossils could be found here. This was followed by the Secondary period, with highly stratified rocks, sandstones, limestones, gypsum and many other layers, filled with fossils. Finally, the most recent were the generally unconsolidated deposits of gravels, sand and clays, corresponding to the Tertiary period.

Rather than accepting that the earth’s crust had formed in a mere six thousand years, Abraham Werner speculated that the older Primary and Transition rocks had formed more than a million years ago, by precipitation from a universal ocean that once enveloped the whole world. His theory implied that the order of rocks he had identified in Saxony would be found elsewhere. If his observations were right, the consequences of his findings were huge, as they were proof that locked within the earth’s crust was evidence of distinct periods in its formation. By identifying an order in the layers of rock, Werner was offering the world a glimpse of prehistory.

Even more perplexing amid the lecture-rooms of deans and bishops at Oxford was a new theory put forward by a Scotsman, James Hutton. He did not accept Werner’s view that the older rocks had precipitated from a universal ocean, but envisaged that they were formed gradually by erosion and deposition. This led him to speculate that the history of the earth was so vast it was almost immeasurable.

From his observations Hutton inferred that the earth was caught in an endless cycle of forming and re-forming the landscape: cycles in which rivers carried sediment from the land to the sea; layers of sediment gently accumulated and compacted into stone on the sea floor, until earth movements lifted the layers out of the sea, folding the different strata to form a new landscape. Since, he reasoned, the erosion of land and the accumulation of sediment take millions of years, the only conclusion was that the landscape had formed over millennia. In his book, Theory of the Earth, he wrote of the earth’s history, ‘there is no vestige of a beginning and no prospect of an end’.

The ideas of Hutton, Werner and others opened the door to an unfamiliar landscape as well as a vast, unknown history of the earth. This abyss of geological time was almost as strangely unbelievable as the vastness of stellar space opened up by Copernicus in astronomy two centuries earlier. The new theories questioned the long-established chronology for the earth’s age of Archbishop Ussher, and with it, the authority of the Bible. Many thinkers felt that this was a dangerous pursuit. Richard Kirwan, President of the Royal Academy in Ireland, was one of several leading thinkers to ridicule Hutton’s claims, pointing out that this was ‘fatal’ to the account in Moses and therefore a threat to morality. Hutton’s theory was so obviously flawed that Kirwan had found it quite unnecessary to even read it!

William Buckland, brought up in the heart of the Anglican establishment but drawn to a rigorous, scientific approach to gathering evidence, was eager to understand the true history of the globe within which fossils could be correctly understood. Wishing to reconcile the two seemingly opposing sides of his nature, he dedicated himself to proving that religion and science did not stand opposed to each other, but were complementary. For him, geology was a ‘master science’ through which he could investigate the signature of God.

In 1813, when Buckland was appointed Reader in Mineralogy at Oxford, such was his enthusiasm to make sense of the apparently conflicting opinions about the earth’s history that he embarked on a detailed study of all the rocks of England, travelling with his friend, George Bellas Greenough. Greenough had helped to found the Geological Society of London in 1807. This began as a ‘little talking Geological Dinner Club’ in a central London tavern, and had rapidly blossomed into a scientific society which aimed to ‘make geologists acquainted with each other, stimulate their zeal … and contribute to the advance of Geological Science’.

Touring with Greenough, Buckland aimed to construct a geological map for the Society of all the strata they could identify, showing the different layers of rock in each region and comparing the fossils within them. Would the layers of rock in England correspond to those in the European rocks? What did the different formations reveal about prehistory?

With infectious enthusiasm, Buckland also enlisted the support of his long-standing friend, the intellectual Reverend William Conybeare, who had graduated from Oxford just before Buckland, taking a first in classics at Christ Church with effortless ease. The unconventional party also called upon ‘the zealous interest of some ladies of high culture at Penrice Castle, Lady Mary Cole and the Misses Talbots’, and any other like-minded individuals they met along the way. Buckland’s energetic and novel approach, which would not be constrained by centuries of Oxford tradition, was viewed with more than a little suspicion.

Whereas most gentlemen’s travelling carriages would have been of a certain standard, with an elegantly appointed interior matched, perhaps, by a smartly painted exterior and with discreet uniformed staff in attendance, William Buckland’s carriage provided a very different travelling experience. The sturdy frame was specially strengthened to allow for heavy loads of rocks; the front was fitted with a furnace and implements for assays and analysis of the mineral content of the stone; and there was scarcely room to sit amid the curiosities and fossils heaped into every available space.

Gossip abounded, too, about Buckland’s other little eccentricities. It was the custom for early geologists to carry out their fieldwork in the full splendour of a gentleman’s suit, with academic robes and even a top-hat. When travelling in the mail, Buckland was not beyond dropping his hat and handkerchief in the road to stop the coach if he spotted an interesting rock. On one occasion he happened to fall asleep on the top of the coach. An old woman, eyeing his bulging pockets with growing interest, eventually couldn’t resist emptying them, only to find to her astonishment that the gentleman, for all his finery, had pockets full of nothing but stones.

Sometimes Buckland rode a favourite old black mare, usually burdened with heavy bags and hammers. It was said that the mare was so accustomed to her master’s ways that even if a stranger was riding her, she would stop at every quarry and nothing would persuade her to advance until her rider had dismounted and pretended to examine the surrounding stones. Buckland became so expert on the rocks of England that his ‘geological nose’ could even tell him his precise locality. Once, when riding to London with a colleague on a very dark night, they lost their way. To his friend’s astonishment Buckland dismounted and, grabbing a handful of soil, smelled it and declared, ‘Ah Uxbridge!’