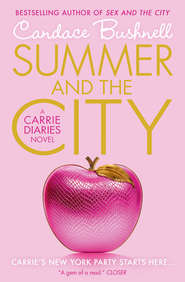

скачать книгу бесплатно

“Is there any other? He should be here somewhere. If you trip across a very small man with a voice like a miniature poodle, you’ll know you’ve found him.”

In the next second, David Ross is halfway across the room and Samantha is sitting on a strange man’s lap.

“Over here.” She waves from the couch.

I push past a woman in a white jumpsuit. “I think I just saw my first Halston!”

“Is Halston here?” Samantha asks.

If I’m at the same party with Halston and Kenton James, I’m going to die. “I meant the jumpsuit.”

“Oh, the jumpsuit,” she says with exaggerated interest to the man beneath her. From what I can see of him, he’s tan and sporty, sleeves rolled up over his forearms.

“You’re killing me,” he says.

“This is Carrie Bradshaw. She’s going to be a famous writer,” Samantha says, taking up my moniker as if it’s suddenly fact.

“Hello, famous writer.” He holds out his hand, the fingers narrow and burnished like bronze.

“This is Bernard. The idiot I didn’t sleep with last year,” she jokes.

“Didn’t want to be another notch in your belt,” Bernard drawls.

“I’m not notching anymore. Don’t you know?” She holds out her left hand for inspection. An enormous diamond glitters from her ring finger. “I’m engaged.”

She kisses the top of Bernard’s dark head and looks around the room. “Who do I have to spank to get a drink around here?”

“I’ll go,” Bernard volunteers. He stands up and for one inexplicable moment, it’s like watching my future unfold.

“C’mon, famous writer. Better come with me. I’m the only sane person here.” He puts his hands on my shoulders and steers me through the crowd.

I look back at Samantha, but she only smiles and waves, that giant sparkler catching the last rays of sunlight. How did I not notice that ring before?

Guess I was too busy noticing everything else.

Like Bernard. He’s tall and has straight dark hair. A large, crooked nose. Hazel-green eyes and a face that changes from mournful to delighted every other second, as if he has two personalities pulling him in opposite directions.

I can’t fathom why he’s paying me so much attention, but I’m mesmerized. People keep coming up and congratulating him, while snippets of conversation waft around my head like dandelion fluff.

“You never give up, do you—”

“Crispin knows him and he’s terrified—”

“I said, ‘Why don’t you try diagramming a sentence—’”

“Dreadful. Even her diamonds looked dirty—”

Bernard gives me a wink. And suddenly his full name comes back to me from some old copy of Time magazine or Newsweek. Bernard Singer? The playwright?

He can’t be, I panic, knowing instinctively he is.

How the hell did this happen? I’ve been in New York for exactly two hours, and already I’m with the beautiful people?

“What’s your name again?” he asks. “Carrie Bradshaw.” The name of his play, the one that won the Pulitzer Prize, enters my brain like a shard of glass: Cutting Water.

“I’d better get you back to Samantha before I take you home myself,” he purrs.

“I wouldn’t go,” I say tartly. Blood pounds in my ears. My glass of champagne is sweating.

“Where do you live?” He squeezes my shoulder. “I don’t know.”

This makes him roar with laughter. “You’re an orphan. Are you Annie?”

“I’d rather be Candide.” We’re edged up against a wall near French doors that lead to a garden. He slides down so we’re eye-level.

“Where did you come from?”

I remind myself of what Samantha told me. “Does it matter? I’m here.”

“Cheeky devil,” he declares. And suddenly, I’m glad I was robbed. The thief took my bag and my money, but he also took my identity. Which means for the next few hours, I can be anyone I want.

Bernard grabs my hand and leads me to the garden. A variety of people—men, women, old, young, beautiful, ugly—are seated around a marble table, shrieking with laughter and indignation as if heated conversation is the fuel that keeps them going. He wriggles us in between a tiny woman with short hair and a distinguished man in a seersucker jacket.

“Bernard,” the woman says in a feathery voice. “We’re coming to see your play in September.” Bernard’s response is drowned out, however, by a sudden yelp of recognition from the man seated across the table.

He’s enveloped in black, a voluminous coat that resembles a nun’s habit. Brown-shaded sunglasses hide his eyes and a felt hat is pressed over his forehead. The skin on his face is gently folded, as if wrapped in soft white fabric.

“Bernard!” he exclaims. “Bernardo. Darling. Love of my life. Do get me a drink?” He spots me, and points a trembling finger. “You’ve brought a child!”

His voice is shrill, eerily pitched, almost inhuman. Every cell in my body contracts.

Kenton James.

My throat closes. I grab for my glass of champagne, and drain the last drop, feeling a nudge from the man in the seersucker jacket. He nods at Kenton James. “Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain,” he says, in a voice that’s pure patrician New England, low and assured. “It’s the grain alcohol. Years of it. Destroys the brain. In other words, he’s a hopeless drunk.”

I giggle in appreciation, like I know exactly what he’s talking about. “Isn’t everyone?”

“Now that you mention it, yes.”

“Bernardo, please,” Kenton pleads. “It’s only practical. You’re the one who’s closest to the bar. You can’t expect me to enter that filthy sweating mass of humanity—”

“Guilty!” shouts the man in the seersucker.

“And what are you wearing under that dishabille?” booms Bernard.

“I’ve been waiting to hear those words from your lips for ten years,” Kenton yips.

“I’ll go,” I say, standing up.

Kenton James breaks into applause. “Wonderful. Please take note, everyone—this is exactly what children should do. Fetch and carry. You must bring children to parties more often, Bernie.”

I tear myself away, wanting to hear more, wanting to know more, not wanting to leave Bernard. Or Kenton James. The most famous writer in the world. His name chugs in my head, picking up speed like The Little Engine That Could.

A hand reaches out and grabs my arm. Samantha. Her eyes are as glittery as her diamond. There’s a fine sheen of moisture on her upper lip. “Are you okay? You disappeared. I was worried about you.”

“I just met Kenton James. He wants me to bring him alcohol.”

“Don’t leave without letting me know first, okay?”

“I won’t. I never want to leave.”

“Good.” She beams, and goes back to her conversation.

The atmosphere is revved up to maximum wattage. The music blares. Bodies writhe, a couple is making out on the couch. A woman crawls through the room with a saddle on her back. Two bartenders are being sprayed with champagne by a gigantic woman wearing a corset. I grab a bottle of vodka and dance my way through the crowd.

Like I always go to parties like this. Like I belong.

When I get back to the table, a young woman dressed entirely in Chanel has taken my place. The man in the seersucker jacket is pantomiming an elephant attack, and Kenton James has pulled his hat down over his ears. He greets my appearance with delight. “Make way for alcohol,” he cries, clearing a tiny space next to him. And addressing the table, declares, “Someday, this child will rule the city!”

I squeeze in next to him.

“No fair,” Bernard shouts. “Keep your hands off my date!”

“I’m not anyone’s date,” I say.

“But you will be, my dear,” Kenton says, blinking one bleary eye in warning. “And then you’ll see.” He pats my hand with his own small, soft paw.

Chapter Two

Help!

I’m suffocating, drowning in taffeta. I’m trapped in a coffin. I’m . . . dead?

I sit up and wrench free, staring at the pile of black silk in my lap.

It’s my dress. I must have taken it off sometime during the night and put it over my head. Or did someone take it off for me? I look around the half darkness of Samantha’s living room, crisscrossed by eerie yellow beams of light that highlight the ordinary objects of her existence: a grouping of photographs on the side table, a pile of magazines on the floor, a row of candles on the sill.

My head throbs as I vaguely recall a taxi ride packed with people. Peeling blue vinyl and a sticky mat. I was hiding on the floor of the taxi against the protests of the driver, who kept saying, “No more than four.” We were actually six but Samantha kept insisting we weren’t. There was hysterical laughter. Then a crawl up the five flights of steps and more music and phone calls and a guy wearing Samantha’s makeup, and sometime after that I must have collapsed on the futon couch and fallen asleep.

I tiptoe to Samantha’s room, avoiding the open boxes. Samantha is moving out, and the apartment is a mess. The door to the tiny bedroom is open, the bed unmade but empty, the floor littered with shoes and articles of clothing as if someone tried on everything in her closet and cast each piece away in a rush. I make my way to the bathroom, and weaving through a forest of bras and panties, step over the edge of the ancient tub and turn on the shower.

Plan for the day: find out where I’m supposed to live, without calling my father.

My father. The rancid aftertaste of guilt fills my throat.

I didn’t call him yesterday. I didn’t have a chance. He’s probably worried to death by now. What if he called George? What if he called my landlady? Maybe the police are looking for me, another girl who mysteriously disappears into the maw of New York City.

I shampoo my hair. I can’t do anything about it now.

Or maybe I don’t want to.

I get out of the tub and lean across the sink, staring at my reflection as the mist from the shower slowly evaporates and my face is revealed.

I don’t look any different. But I sure as hell feel different.

It’s my first morning in New York!

I rush to the open window, taking in the cool, damp breeze. The sound of traffic is like the whoosh of waves gently lapping the shore. I kneel on the sill, looking down at the street with my palms on the glass—a child peering into an enormous snow globe.

I crouch there forever, watching the day come to life. First come the trucks, lumbering down the avenue like dinosaurs, creaky and hollow, raising their flaps to receive garbage or sweeping the street with their whiskery bristles. Then the traffic begins: a lone taxi, followed by a silvery Cadillac, and then the smaller trucks, bearing the logos of fish and bread and flowers, and the rusty vans, and a parade of pushcarts. A boy in a white coat pumps the pedals of a bicycle with two crates of oranges attached to the fender. The sky turns from gray to a lazy white. A jogger trips by, then another; a man wearing blue scrubs frantically hails a taxi. Three small dogs attached to a single leash drag an elderly lady down the sidewalk, while merchants heave open the groaning metal gates on the storefronts. The streaky sunlight illuminates the corners of buildings, and then a mass of humanity swarms from the steps beneath the sidewalk. The streets swell with the noise of people, cars, music, drilling; dogs bark, sirens scream; it’s eight a.m.

Time to get moving.

I search the area around the futon for my belongings. Tucked behind the cushion is a heavy piece of drafting paper, the edge slightly greasy and crumpled, as if I’d lain clutching it to my chest. I study Bernard’s phone number, the numerals neat and workmanlike. At the party, he made a great show of writing out his number and handing it to me with the statement, “Just in case.” He pointedly didn’t ask for my number, as if we both knew that seeing each other again would have to be my decision.

I carefully place the paper in my suitcase, and that’s when I find the note, anchored under an empty bottle of champagne. It reads:

Dear Carrie,

Your friend George called. Tried to wake you but couldn’t. Left you a twenty. Pay me back when you can. Samantha

And underneath that, an address. For the apartment I was supposed to go to yesterday but didn’t. Apparently I called George last night after all.

I hold up the note, looking for clues. Samantha’s writing is strangely girlish, as if the penmanship part of her brain never progressed beyond seventh grade. I reluctantly put on my gabardine suit, pick up the phone, and call George.

Ten minutes later, I’m bumping my suitcase down the stairs. I push open the door and step outside.

My stomach growls as if ravenously hungry. Not just for food, but for everything: the noise, the excitement, the crazy buzz of energy that throbs beneath my feet.

I hail a taxi, yank open the door and heave my suitcase onto the backseat.

“Where to?” the driver asks.

“East Forty-seventh Street,” I shout.

“You got it!” the driver says, steering his taxi into the melee of traffic.

We hit a pothole and I’m momentarily launched from my seat.

“It’s those damn New Jersey drivers.” The cabbie shakes his fist out the window while I follow suit. And that’s when it hits me: It’s like I’ve always been here. Sprung from the head of Zeus—a person with no family, no background, no history.

A person who is completely new.

As the taxi weaves dangerously through traffic, I study the faces of the passersby. Here is humanity in every size, shape, and hue, and yet I’m convinced that on each face I divine a kinship that transcends all boundaries, as if linked by the secret knowledge that this is the center of the universe.

Then I clutch my suitcase in fear.

What I said to Samantha was true: I don’t ever want to leave. And now I have only sixty days to figure out how to stay.