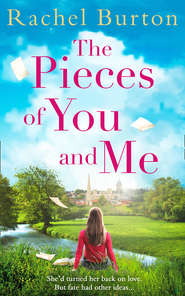

скачать книгу бесплатно

‘I’m sorry,’ I said. ‘I know it was meant to be a treat but I hate them. They don’t suit me like they suit you.’

Gemma looked at me then, still smiling. ‘They’re fine,’ she said. ‘They always look a bit alarming when you first have them done, but they’ll fade and you’ll thank me when you see the wedding photos.’

‘Will I?’

‘Eyebrows are the windows to the soul,’ she said.

‘I thought that was eyes?’

‘Window frames then.’ She laughed, linking her arm through mine. I’ve always wondered what it must be like to feel as carelessly happy as Gemma.

‘Come on,’ she said. ‘Let’s go and get that coffee.’

…The day you left for boarding school I didn’t want to let you go. We stood outside your house, your father’s car packed up with your things, my arms wrapped around your waist, your chin on the top of my head. Even at eleven you were head and shoulders taller than me.

‘Come along, Rupert, please,’ your father said. I could hear the irritation in his voice. He was always impatient when I was around. Maybe he was impatient when I wasn’t around too, but I did feel that his impatience was reserved especially for me.

You pulled away, pushing your glasses up your nose and looking at me. I remember your eyes seemed bluer than ever that afternoon.

‘I’m still here, Jessie,’ you said. ‘Whenever you need me.’ But I knew I wouldn’t see you until the Christmas holidays and when you’re eleven the distance between September and Christmas seems enormous, insurmountable, impassable.

You got into the back of the car and your father pulled away, off to your expensive new school in London. It felt like you were going forever. It felt as though it was the end. You looked out of the rear window as the car turned out of the bottom of the road and you waved briefly. I felt as though I’d never see you again.

But life carried on much as it always had, even though you weren’t there. I moved up into the Senior Building of my all-girls school and I made friends who helped me keep my mind off you, who helped to fill the gaping hole you’d left behind.

Caitlin and Gemma were the only girls like me at school – my grandmother had high ideas about my education, but I don’t think she’d thought through how hard it would be for me to fit in. Caitlin and Gemma and I were ordinary – we didn’t have trust funds or long limbs and blonde hair and our fathers weren’t ‘something in the City’.

But they always saw me for who I was rather than as ‘Rupert Tremayne’s friend’ …

6 (#ulink_aca29bcd-1e1c-59ce-b952-2c82f6e30aa4)

RUPERT (#ulink_aca29bcd-1e1c-59ce-b952-2c82f6e30aa4)

Even though in the end she hadn’t believed him, it had always been Jess. From the day he asked her to marry him in the school playground he knew. Admittedly, he didn’t really know what it was that he knew when he was six, but it was a feeling; a sense of the way things were meant to be. Even years later, after he’d left her standing at the departure gate at Heathrow airport, he had still known. None of the women he’d tried to lose himself in at Harvard could compare, not even Camilla – especially not Camilla. He’d always wanted them to be Jess and they never could be. He’d stopped dating completely in the end.

He could clearly remember the day he first realised his feelings for Jess had slipped from best friends to something more, something much more. It was the Christmas holidays before their GCSEs. Something about Jess had changed that winter; it felt as though she was sliding away from him. She was starting to have a life that he wasn’t a part of and she talked about the parties she had been to and the boys Gemma and Caitlin had giggled over, the boys they had kissed.

‘Did you kiss anyone?’ he’d asked, unable to hide the jealousy from his voice.

She’d shaken her head. ‘Not this time,’ she’d said with a grin.

He had wanted to kiss her then, but he hadn’t had the courage to do anything except think about what that would be like and it had taken him until the following summer to admit what was happening – that they couldn’t just be friends anymore.

He’d always thought he’d asked her too soon, that she hadn’t been ready for a relationship when she was sixteen. But she had known as well as he had that they had both reached the point of no turning back.

Over the last week, since seeing Jess again, Rupert had had to stop himself from tracking her down. He knew Gemma worked at Kew. It would be easy enough to call her, to find out where Jess was, what her phone number was. Gemma had seemed quite keen to push the two of them back together, had even told him Jess was single. What harm could there be in asking Jess if she wanted to meet for a coffee next time he was in London?

But he had pushed her before, when they were sixteen, and again, when they were twenty-one, when they were both lost in the grief of losing Jess’s father. He didn’t want to be that person again and Jess had made no move to get in touch with him. He tried to remind himself that walking away from her outside her hotel had been the right thing to do.

When the thick gold-embossed envelope appeared in his pigeonhole at work it had felt like a lifeline. Gemma had invited him to her wedding after all. He had thought she’d been joking when she mentioned it in the pub. He hadn’t needed to call her in the end because Gemma had given him a second chance. He knew this would be the last chance he would get. It was now or never.

JULY 2017 (#ulink_f9f543a7-a8ad-5c60-9b93-318718aba027)

7 (#ulink_1c3916a0-b1c9-52dc-a0fc-c60195b4bdee)

JESS (#ulink_1c3916a0-b1c9-52dc-a0fc-c60195b4bdee)

I woke up on the morning of Gemma’s wedding feeling as though I’d been hit by a truck. Not today, I thought. Please not today.

Five years previously I had come down with glandular fever. I’d known other people who had had it, I knew that it could take weeks, even months, to recover, but for me something had gone wrong. The virus had triggered something else in my body, something worse, and had left me sick and weak for years. Up until a year or so ago I would wake up most mornings feeling like this – every bone in my body aching, my glands swollen, my head pounding. I knew when I stood up I would be dizzy and that everything I did, from cleaning my teeth to brushing my hair, would be exhausting; that every movement would feel as though I was walking through jam.

Over the years, the bad days became less frequent and I was able to live a more normal life – if going to bed at 9 p.m. and barely drinking or socialising could be considered a normal life for a woman my age. My thirtieth birthday party ended at 6 p.m. and the strongest substance imbibed by me was Earl Grey tea.

These days I still got tired easily and, towards the end of the day, the bone-aching weariness would return. But as long as I took my painkillers and my other medication I could usually manage most situations.

I lay in bed racking my brains, trying to work out what I’d done to trigger a flare-up like this. I knew the run-up to Gemma’s wedding – the endless hair and beauty trials, the rehearsal dinner, the dress fittings and the stress of the last-minute arrangements – would be exhausting, but I’d tried to get early nights, tried not to drink and tried to do the things that I knew helped me. Yet, despite my efforts the wheels had fallen off on the one day I needed them more than ever.

The only thing I could think of was that London was enjoying a brief heatwave and, although I loved the summer time, the heat could be a trigger for my symptoms – especially in an old hotel without air conditioning, when I hadn’t slept well.

I wasn’t going to admit, even to myself, that I hadn’t been sleeping well recently because I’d been up late night after night reading my old journals, poring over the box of photos, lost in memories of the past. And I wasn’t going to admit that my insomnia had increased along with my anxiety at seeing Rupert again today. My stomach churned with a mix of dread and excitement at the thought.

I took some deep breaths and tried to remember the times I’d had to battle flare-ups like this before – like when the deadline for my second novel was looming, or Gemma’s engagement party. I’d got up, taken my meds and got on with the day. As I sat up in bed, swinging my legs over the side and reaching for my medication bag, I tried not to remember the consequences of those times I’d battled through, tried not to remember how they had left me depleted for weeks.

By the time Caitlin knocked on my hotel room door to collect me, I was showered and dressed and ready to go and get my hair and make-up done.

I watched Caitlin’s face fall as I opened the door.

‘Are you OK?’ she asked.

I forced a smile. ‘I’m fine,’ I said. ‘Honestly, it’s just been a long time since you saw me without make-up on!’

She looked at me for a minute, scrutinising me.

‘If you need anything today just ask me, won’t you?’ she said.

I opened my mouth to tell her again that I was fine, but I knew I couldn’t lie to her. Caitlin knew me too well.

‘Just ask,’ she repeated, and I nodded. ‘Now come on,’ she went on. ‘We can’t leave the bride-to-be waiting any longer. She’s phoned me three times this morning already. Has she phoned you?’

‘I switched my phone off.’ I grinned.

‘Sensible girl,’ she said, taking my arm and leading me off to the bridal suite.

*

An hour and a half later we sat in Gemma’s room surrounded by the detritus left behind when three women get ready for a wedding. The hair and make-up people had left and the photographer, who had been taking photographs of us getting ready, had gone off to take some photos of Mike and his best man.

I’d scrubbed up well considering how bad I felt – the make-up artist had her work cut out with me, but she’d worked magic. Even I couldn’t tell how bad I looked underneath when I saw my reflection and the dark blue of the bridesmaid’s dress brought out the green in my eyes. I almost looked healthy, and my ridiculous Billion Dollar Brows had calmed down just as Gemma had promised they would.

Gemma sighed audibly.

‘Cold feet, Gem?’ Caitlin joked.

‘Dad,’ Gemma said quietly. ‘James walking me down the aisle just won’t be the same. I wish he could be here.’

Neither Caitlin nor I said anything. Neither of us knew what to say. Neither of us had ever known what to say since the day, just over a decade ago, just before Rupert left, when Gemma’s father had been arrested for corporate espionage and fraud. It turned out that’s how he paid her school fees, amongst other things. Neither of us knew if Gemma had ever visited him in prison and we didn’t know if she’d seen him since he got parole and went to live in another part of the country. We never talked about Gemma’s father and we didn’t even know if he knew she was getting married. Her brother was giving her away today and we left it at that.

‘And soon we’ll all be married,’ Gemma went on, sounding rather maudlin. ‘Old matrons who never get to see each other often enough.’

‘We don’t get to see each other often enough now,’ Caitlin said.

‘And I still won’t be married,’ I disagreed. ‘I’m not even dating anyone.’

‘Oh, but you will be after today,’ Gemma said. ‘As soon as you see Rupert the two of you will fall madly in love again, and then you won’t even be in London anymore.’

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ I replied. ‘I’ll always be in London.’

‘No, you won’t,’ she said. ‘You’ll marry him and then you’ll move to York and we’ll exchange Christmas cards once a year with a circular letter inside full of lies and exaggerations about how brilliant our lives are and how wonderful our children are and—’

‘For God’s sake,’ I interrupted this depressing dialogue. ‘What on earth are you talking about? It’s you who invited him to the wedding anyway.’

‘Cold feet, Gem?’ Caitlin said again, with a grin.

Gemma was saved from replying by a knock on the door. She tried to jump up to open it but the full skirt of her wedding dress prevented her, so I went instead. My mum and James were standing outside.

‘It’s nearly time,’ Mum said, as I stood aside to let them in. James went over to his sister to make a fuss of her and Mum took me to one side.

‘Rupert’s here,’ she whispered. She’d been almost as excited about him coming to the wedding as Gemma had been. ‘He looks ever so handsome. He hasn’t changed much, has he?’

Something inside me unravelled. I’d been looking forward to seeing him again more than I was prepared to admit and part of me had wondered if he would turn up. I smiled my first genuine smile of the morning.

‘Are you OK?’ she asked. ‘You don’t look very well.’ The make-up wasn’t fooling Mum, clearly.

‘I just slept badly,’ I said. ‘It’s so hot.’

Mum looked at me as though she didn’t believe me and pulled me gently into the corridor away from everyone else.

‘I know you’ve not been sleeping properly since Gemma’s hen do,’ she said. ‘I can hear you still up when I go to the loo in the night. I’m worried about you. Tell me what’s going on.’

I sighed and looked away from her. ‘Memories,’ I said. ‘Seeing him again has just brought everything back. I can’t stop thinking about that summer, about Dad …’ As I trailed off I felt her fingers brush against my cheek and I turned to look at her again. I saw her blink back the tears that always came whenever anyone mentioned my father. I wondered if she would ever get over him, if she would ever move on. Mum and I were the same, both waiting together for our lives to start again.

‘Maybe it’s a good thing,’ she said quietly. ‘Maybe it’s time to open your heart again.’

I shook my head. ‘Too much has happened,’ I said. ‘Too much has changed.’

‘Don’t burn your bridges, Jess. Try not to think about the past or the future today; try to enjoy yourself. Drink champagne, laugh, dance with Rupert.’

‘I don’t know.’

‘You and Rupert were always inseparable,’ she interrupted. ‘Maybe you both need that again.’

I opened my mouth to speak, to contradict her, but I knew that in a way she was right, that part of me did wonder what it would be like to spend the day with him again. Part of me was curious as to where it would lead – the part of me that regretted not swapping numbers with him in York, that hadn’t wanted to watch him walk away.

‘Just see what happens,’ Mum said. ‘Just for today.’

‘OK,’ I replied. ‘Just for today.’

…The summer that we turned twelve was the first birthday we hadn’t spent together, the first time we hadn’t had a joint party. We had a short, awkward phone conversation and you sent me a card with a cat on the front of it.

By that summer I’d begun to grow used to you not being around. Even though you’d been home for Christmas and Easter I felt as though I’d hardly seen you – your parents were always taking you off for extra tutoring or educational trips. I’d started to spend more time with the kids who lived on our block, just like we had when we were younger, even though we all went to different schools now. Growing up on those streets that backed onto Midsummer Common, onto the River Cam, having all known each other since before we could remember, was a common denominator. We hung around together even though we weren’t really sure if we liked each other anymore. I don’t think I was the only one who missed you though.

That afternoon in July we were all playing a rather undisciplined game of rounders on the Common. I’d been consigned to deep field as usual – always hopeless at sports. I had a headache and was considering going home. I heard you before I saw you, the squeal of your bike brakes, the skid as your back wheel flipped round towards me, cutting me off from everybody else.

And there you were suddenly. Home. Standing in front of me in your Arsenal away shirt. It was summer, and the holidays felt as though they could go on forever. There was no way they could keep us apart all summer. You smiled that smile that gave me butterflies, even though it was another four years before I realised why. You’d grown again, already well on your way to six foot – your bike was too small for you, your jeans too short. You’d exchanged your glasses for contact lenses, tired of being called the Milky Bar Kid by the boys at school.

You were there.

‘Hop on,’ you said. And just like that the rest of the world stopped existing, as it always did when we were together. I jumped on the back of your bike and we flew across Cambridge, screaming with joy. Summer began that afternoon.

As teenagers we only saw each other in the school holidays and the older we got, the more things felt as though they were changing. I had my own friends – people you didn’t really know, who you only met sporadically. You never really talked about boarding school, never really told me about any friends you’d made there. It was almost as though you thought the time we spent apart didn’t really exist.

But I was still in Cambridge and the life I had when you weren’t there merged with the life I had whenever you came back. Caitlin and Gemma slowly filled up the gaps you had left behind, and we became as close as you and I had been. The three of us would wander around town together, trying on and discarding every outfit in River Island, sitting for hours in Burger King, whispering secrets to each other as we shared cups of coffee and, after we turned fourteen, filling up the little tin foil ashtrays with the butts of our Silk Cut cigarettes that Gemma, who looked the oldest of all of us, would buy. I thought, when you came home that summer, that you would disapprove of my new habit until I saw the packet of Marlboro in your shirt pocket.

When you were home you always seemed so alone. Your school friends, if you had any, miles away and your old friends distanced from you by your being away. We forget so quickly as teenagers. We are resilient, moving on to the next group of friends, the next adventure so easily. Sometimes I’d see you, playing football on the Common with the boys from our street. You and John were thick as thieves still – you always would be – but there was something about you then that made you seem aloof, as though you’d been left behind.

No, not left behind. Rupert Tremayne was never left behind. You were always light years ahead of all of us.

Every evening you would squeeze through the gap in the fence that divided off the bottoms of our gardens, the gap we’d made as children, to spend time with me. We’d lie on our backs in Mum’s apple orchard and watch the sky change colour. We’d wish upon a star and smoke cigarette after cigarette – swallowing half packets of peppermints before we went home, foolishly believing that would stop our parents finding out we smoked.

Sometimes your fingers would find mine and you’d hold my hand like you did at my grandmother’s funeral.

‘I’m still here,’ you’d say. ‘Even though I’m miles away, I’m always yours, Jessie.’

But everything felt different, as though a chasm was opening up between us. I wondered if things would have been different had you been born a girl or I a boy – would that have helped us maintain our sibling-like closeness? The onset of puberty had highlighted the differences between us, fascinating us as much as it scared us. I started to wonder what would become of us, where we could possibly go from here. I started to wonder how I would feel when you eventually told me about your first girlfriend. I started to wonder how quickly you would forget me then. Because it seemed obvious to me the summer we turned fifteen that it was only a matter of time before you got a girlfriend. The willowy, blonde trust-fund girls at my school had had their eyes on you for years.

There was nothing I could do to stop it. I was so sure of our fate when I was fifteen. I had always thought nothing could come between us, but then as we started our slow progression from childhood to adulthood, I was beginning to see that one day, something would …

8 (#ulink_3a1c8f37-279e-5efe-84ce-b8daa92da3a5)

JESS (#ulink_3a1c8f37-279e-5efe-84ce-b8daa92da3a5)

Kew Gardens is probably the most beautiful place in London to get married. I couldn’t believe Gemma was having her wedding here after organising so many for other people. And I couldn’t believe I wasn’t going to be well enough to enjoy it. I don’t know how I made it through the wedding ceremony.

As if she knew how I was feeling, Caitlin put an arm carefully and quietly around my waist as Gemma and Mike said their vows – if it hadn’t been for that I think I would have passed out. Thanks to her, I don’t think anyone noticed. She had a word with the photographer too, who did all the photos that I was needed for as quickly as possible.

‘Why don’t you go and talk to Rupert,’ Caitlin said. ‘No harm in catching up if you feel well enough?’

I hesitated for a moment, unsure of myself, remembering what Mum had said to me – to just take today as it comes, enjoy myself. I smiled at Caitlin and walked away from her towards Rupert.