Полная версия:

Christina Queen of Sweden: The Restless Life of a European Eccentric

Christina Queen of Sweden

Veronica Buckley

For C.R.B.,

my father,

who’s always known how to tell a good story

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

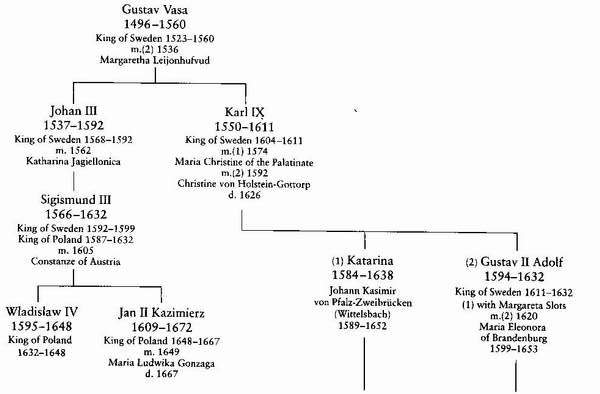

Christina’s Family Tree (Paternal)

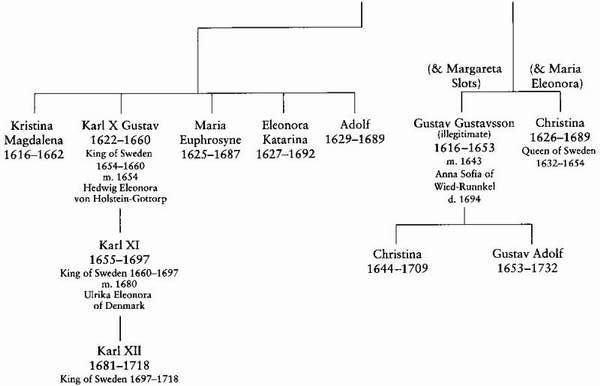

Christina’s Family Tree (Maternal)

PART ONE

Prologue

Birth of a Prince

Death of a King

The Little Queen

Love and Learning

Acorn Beneath an Oak

Warring and Peace

Pallas of the North

Tragedy and Comedy

Hollow Crown

The Road to Rome

Abdication

PART TWO

Crossing the Rubicon

Rome at Last

Love Again

Fair Wind for France

The Rising Sun

Fontainebleau

Aftermath

Old Haunts, New Haunts

Débâcle

Mirages

Glory Days

Journey’s End

P.S.

About the author

From Music to Mondaleschi

LIFE at a Glance

FAVOURITE NOVELS

A Writing Life

About the book

Queen Christina’s Myth

Read on

If You Loved This, You Might Like…

FIND OUT MORE

Epilogue

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Author’s Notes

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

Christina’s Family Tree (Paternal)

Christina’s Family Tree (Maternal)

Prologue

Nowadays, if you have a few pounds to spare, you can buy a copy of The Times, printed on the day you were born. Leafing through the pages, you glean something of the world as it was at the time of your own arrival. You see recorded the lives of those who made your world, their interests and values, what motivated them, and what they feared. You see the world that has shaped and bordered your life and, in significant measure, made you what you are.

What, then, was Christina’s world? What forces shaped her; what ideas framed her mind? She was born in 1626, into a world overwhelmingly European, though the bounty and burdens of the great era of exploration had opened its eyes to other lands beyond. American silver framed the holy icons of the pious, and the soft white hand of many a countess sparkled with jewels from the East, while the first African ‘indentured servants’ had begun their woeful voyage aboard a Dutch cargo ship. Knowledge had come, too, with the diamonds and the silver, but Europe’s ‘gentleman-travellers’ still seldom ventured to very distant shores in search of it. It was left to the sailors and traders and priests to make the longest journeys, and to bring the tales back home.

Christina’s was a cold world, the coldest time Europe had known for thousands of years, the ‘Little Ice Age’ which balked the harvests and froze the seas. Fires blazed on ice-thickened rivers, and birds were seen to drop from the skies in mid-flight, frozen to sudden death. Christina’s world was a dirty world of sudden illness and doubtful water and scanty, tainted food, where peasants and beggars faced hunger as routinely as the sunrise. It was a man’s world, where women had little public power; high rank might soften the outlines, but too frequent childbirth was most women’s lot. And it was a familiar world, a world of small towns where great families ruled, where faces were known and strangers few, and secrets hard to keep.

Above all, Christina’s world was a world at war, the great Thirty Years War which raged across Europe from 1618 to 1648, claiming countless lives, including that of her own great father. Christina would grow quickly accustomed to it; during the whole of her life, Europe would know barely a single year of peace. Warfare in her world was a normal aspect of government. States and empires grew from it in a savage symbiosis, filling its maw with their choicest fruits, and drawing new wealth from its wake. Christina’s contemporaries accepted it as a fact of life, and reserved their greatest praise for those who waged it successfully.

The finest laurels were still worn by the Habsburg Empire of Spain, whose brilliant armies had dominated Europe for more than a hundred years. But, fearful of new ideas and disdainful of trade, Spain had now begun its long decline. The new road was being paved by its vibrant little brother along the western shores of the continent; in the energetic, enterprising provinces of Holland, the ships and banks and warehouses of a new commercial prosperity were busily being built. Within a few decades, Spain’s political laurels would pass to France, whose brilliant star had yet to rise, and its military honours were even now being captured by Sweden itself, whose innovative armies, seemingly invincible, had pressed deep into Europe, captained by their own splendid King.

The Swedes’ great enemy was the Austrian Habsburg Empire, a vast Catholic power which stretched from Poland to the Czech lands and from Bavaria to Croatia. Since the infamous defenestration of Catholic officials in Prague in 1618, the Empire had been at war, alternately desultory and ferocious, with various Protestant powers. The many German lands which were not within its borders stood as independent states, either Catholic or Protestant, numbering in their confusing hundreds.

No single land of Italy existed, but the marvellous Italian cities, Europe’s most fabulous jewels, still dazzled eye and mind after centuries of cultural pre-eminence. Their most gifted sons had made their way to every corner of the continent, leaving the fruits of their artistry in marble and on canvas, changing perspectives, opening minds, firing the imagination. The papal city of Rome itself had recently enjoyed a great artistic renaissance, encouraged and funded by successive popes intent on re-establishing the primacy of Catholicism after the Protestant Reformation.

England, though not isolated from European life, remained as yet peripheral. Its new King was beginning to set out his claim to absolute rule by divine right, an idea that would spark revolution, and in time engender the downfall of Christina’s world. The King’s nemesis, Oliver Cromwell, was a young country gentleman, still unknown. Shakespeare had lain just ten years in his grave.

To the east, the first Romanov Tsar sat upon the throne of Muscovy. After its long ‘Time of Troubles’, Russia now looked forward with hope, but for decades to come it would be outshone by its dual neighbour, Poland-Lithuania, the largest state in Europe, and Sweden’s longstanding threat from the east. And southward, linking Sweden with the mainland over the much-disputed Baltic Sea, lay the ancient enemy and former ruling power of Denmark.

Despite its military prowess, Sweden itself was undeveloped. In economic and social terms, it was essentially still a medieval land, overwhelmingly rural, exporting its ablest youth to more promising environments, and relying on foreigners for capital and enterprise at home. Throughout the country a series of cold fortress castles, grim stone on the outside and bare-walled inside, contained what little the kingdom possessed of scientific endeavour or cultivated living. But the war booty of recent years had at last allowed it to begin its ascent into the light of culture and learning, and in the 21 years of his youthful reign, Christina’s brilliant father would succeed in dragging and thrusting his backward homeland into the very heart of European life.

Christina’s world was a world of vibrant learning, of philosophy and poetry, of religious scholarship and scientific experiment. It had begun its long, deep love affair with the world of classical antiquity, now resurgent after the exotic lures of the great age of exploration; on the foundations of this ancient world new temples were being built to Greek thinking and the manly virtues of Rome. Renaissance ideas persisted, too, not least in the widespread practice of alchemy, consuming fortunes and lifetimes in a misbegotten search for truth.

And, while Europe’s princes fought among themselves, their Christian world faced two mightier enemies, from without and from within. The external threat was the great Ottoman Empire of the Turks, which at Christina’s birth stretched from Algiers to Baghdad and as far west as Budapest. Late in her life she would hear of a vast Turkish army pitching its tents at the very gates of Vienna. But it was the internal enemy that in the long run would prove the more decisive. With their stumbling, excited experiments, Europe’s ‘natural philosophers’ had begun their challenge to religious orthodoxy. With increasing success, they now strove to provide materialist explanations of the natural world. Though most were repaid with hostility and persecution, and some even with death, no Church, and no state, could stop them. The great march of empirical science had begun, and all ears, willing and unwilling, heard the beat of its tremendous drum.

Christina’s world was a crossroads world, where God still ruled, but men had begun to doubt. She herself would stand at many crossroads, of religion and power, of science and society and sex. And she would prove a dazzling exemplar of her own quixotic era, an exemplar of great, flawed beauty, like the misshapen baroque pearl that would give its name to her vibrant, violent age.

Birth of a Prince

In the spring of 1620, a delegation of German nobles made their way along the Spree river, towards the town of Berlin. The town was not what it had been; years of plague had depleted its people, and its once thriving trade had dwindled to the narrow service of luxury goods to its resident court. Now, among the low wooden buildings, only the vast old castle impressed upon the visitor that Berlin was still a place of power, the residence of the Hohenzollern family of Brandenburg, Electors of the Holy Roman Empire. For just a year, a new Elector, the young Georg Wilhelm, had held that stately office.

Now, towards the castle, the nobles rode, down the bridle path under the linden trees which would one day give their name to the town’s most lovely thoroughfare. The delegation was led by Johann Kasimir, the Count of Pfalz-Zweibrücken, and in his train were two young gentlemen who had joined him from the homeland of his wife, the Princess Katarina of Sweden. One of these was ‘Adolf Karlsson’, a strongly built and handsome man with the blond hair and keen blue eyes of the north. The other, his friend, was Johan Hand, whose diary of their journey was to provide an historic chapter in the annals of their homeland.

The Count was related to the Elector’s wife, Elisabeth, and it was ostensibly to see this princess that he had made his present journey. The visit had been timed strategically, for the Elector Georg Wilhelm himself was not at home, nor did the Count regret his absence. A matter of importance was now at hand, in which the Elector’s mother, the Electress Dowager Anna, would cast the deciding vote. The Count had hopes of persuading her to his own views, and he knew that Anna would hear him more readily if her son was not there to speak against him. The matter at hand was no less than the marriage of Anna’s daughter, Maria Eleonora, and the bridegroom proposed was the Count’s own brother-in-law, Gustav Adolf, King of Sweden. He had made the journey himself, just to have a look at the lady, for ‘Adolf Karlsson’ was in fact the King.

A marriage between Maria Eleonora, now aged twenty, and Gustav Adolf, five years her senior, had been under consideration for some years already. Offers for the hand of the young Countess were not wanting: among her suitors she could boast Gustav Adolf’s cousin, the Crown Prince Wladislaw Vasa of Poland, and Prince Charles Stuart, heir to the English throne. Her father had been ambivalent towards a possible Swedish match, but his son, the new Elector, had taken a clear stand against it. He had no wish to antagonize the Catholic Emperor, or the King of neighbouring Catholic Poland, whose vast country lay only two days’ march from Berlin. The Swedes were already at war there, and Georg Wilhelm thought little of their chance of victory. Though a Calvinist himself, and ruler of a Lutheran state, he felt his sister would do better to marry the Crown Prince of Poland. In the Habsburg lands, not so far to the south, the Emperor had recently reasserted his power over the luckless Protestants of Bohemia, whose ill-starred ‘Winter King’ was the brother of Georg Wilhelm’s own wife. Religious neutrality seemed the wisest course as the match set in Prague began to kindle. But, by family custom, it was the privilege of the Electress to decide her daughter’s marriage, and on this the Swedes had pinned their hopes. An alliance with Brandenburg could strengthen their hand against Poland, and might hasten the formation of a new bloc of Protestant states against the Catholic Habsburgs. The Elector’s fear was Gustav Adolf’s hope.

For his journey now, however, the young King had paid a great personal price. A spirited and warmhearted man, he had been passionately in love with the daughter of one of Sweden’s noblest families, the beautiful Ebba Brahe. Ebba had returned his love, but the King’s strongminded mother had felt that a match between them would not serve Sweden’s dynastic interests. Intriguing and determined, she had set to with a will to break off the romance, at one point even laying her own violent hand on the lovers’ go-between. In due course, she had succeeded. Ebba was married off to the scion of another noble family. The sad and disappointed King dispatched a beautiful letter of farewell, wishing his love ‘a thousand nights of gladness’ in her husband’s arms, and at length he turned his thoughts towards Brandenburg, where his mother’s gaze had long been fixed.

Happily, the object of his present attentions was well formed to incite new passion in the young man’s heart. Maria Eleonora was a genuine beauty, her figure rounded, her face soft and full, with a sweet bow mouth, a strong nose, and large, beautiful eyes. She was blonde, and her manner was lively, giving an impression of girlish gaiety to all those who saw her.

At first, though, it seemed that her young suitor might not succeed in seeing her at all. Her father had died in the previous December, and the court was still in mourning. Dark hangings draped the rooms, and the few permitted candles flickered on his doleful, black-garbed retainers. Five months after his death, the old Elector’s body lay still unburied in the castle chapel. The usual bustling life of the court was suspended, and visitors received only the simplest civilities. But the pulse of youth was strong in the burgeoning spring, and besides, Gustav Adolf could not afford to wait; there was too much to do at home. For a bribe of 300 ducats, he acquired a portrait of the young Countess, and, duly encouraged, arranged a secret rendezvous. It was a Sunday, and all the court was at church, all except Maria Eleonora, who had found some pretext for absenting herself. The Swedes, being Lutheran rather than Calvinist, could not, of course, attend, and soon the meeting was effected in the shade of the trees in the castle park. The Countess, at least, was not disappointed, as the King’s friend would later remind him. ‘Where the girl’s thoughts were, I couldn’t say,’ he wrote, ‘but she didn’t take her eyes off Your Majesty.’1

There was not much else, it seems, in Maria Eleonora’s head. She had chafed at her school lessons, and she had no interest now in learning or literature. But she was lighthearted, prettier than most girls, and at least with a genuine love of music and art. No doubt these things were spoken of in the further meetings which were soon arranged between the two, for the King himself enjoyed them both; he was interested in painting, and he played the lute well. Johan Hand records that the couple met privately several times, that they dined together and conversed at length, and that Gustav Adolf did not depart unkissed. On the whole, he was pleased to have made the journey. The girl’s grandfather and great-uncle had been insane, it was true, but this could hardly count against her, for had not his own uncle and aunt been the same?2

For her part, Maria Eleonora was delighted. She soon discovered the true identity of the handsome ‘Adolf Karlsson’, and, turning her heart where duty lay, promptly fell in love with him. In this, at least, she showed good judgement, for the young King was among the very finest men of his age, able and cultivated, brave, strong, and generous, courteous, farsighted, conscientious, and just, an inspired military leader and a man of profound religious humility, amply deserving the epithet that his dazzled contemporaries would one day accord him – Gustav Adolf the Great. Had he lived in a time of peace, his many gifts might have borne yet finer fruits, but in 1611, when he had come to the throne at the age of only sixteen, his tiny country was already at war with Denmark, and by 1618, at the outbreak of the Thirty Years War, Sweden had embarked on warfare to last a generation, in which the greathearted King, the ‘lion of the north’, was to lose his own life.

But for now, Gustav Adolf’s fine soldier’s reputation can only have added to his attraction. For Maria Eleonora, he seemed the fulfilment of a dream, indeed, the fulfilment of a prophecy, for her father’s own astrologer had once predicted that she would grow up to marry a king. The King himself was not so sure. Though he wanted to marry quickly, a Brandenburg connection was not the only possibility. In the ripening spring, he made his way southward, pausing in the vibrant town of Frankfurt am Main, where books and silks and jewellery were traded in the busy streets beneath the great cathedral. While there, he took the time to purchase a magnificent diamond necklace at a value of almost 9,000 riksdaler – the price of 3,000 cows, no less – borrowing the money from his brother-in-law to do so. As yet, however, he had not decided whose neck the lovely item would adorn.

From Frankfurt, he made his way to Heidelberg, there to cast his eye upon an alternative marriage candidate, the Princess Katharina, sister of Friedrich V, Elector and Prince Palatine of the Rhine, the unhappy ‘Winter King’ of Bohemia. The Swedish King had maintained his incognito, but he was now dressed as an army captain, and disguised by the simple acronym of Gars – Gustavus Adolphus Rex Sueciae – Gustav Adolf, King of Sweden. The Princess, a young lady of generous circumference but, it seems, no great perspicacity, failed to recognize her prospective suitor. She mistook his interested approach for impertinence, declaring to her sister, in imperious French, ‘What intrusive people these Swedes are!’ Alas, among the eleven languages understood by the clever King, French was not the least.3 The portly princess had cooked her goose. Gustav Adolf decided that the pretty little Countess of Brandenburg would suit him better, and in due course he made his way back to Stockholm, dispatching his friend and Chancellor, Axel Oxenstierna, to complete the arrangements in Berlin, while the Countess herself sat down to pen an excited letter to her grudgingly accepting brother. ‘The whole journey was like a play,’ wrote Johan Hand in his diary.4

But if the journey was a romantic comedy, it was not without its dramatic aspects. His search for a wife in the German lands had allowed Gustav Adolf to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the various princes who served as a Protestant bulwark against the Catholic Habsburgs. He was not impressed, and he returned contemptuous of their ‘feebleness, cross-purposes, selfishness, and military incompetence’, an ill omen for the Protestant alliance that he would later attempt to forge.5

In the autumn Maria Eleonora and Chancellor Oxenstierna set out upon the northward road, accompanied by the Electress Dowager and her youngest daughter, Katharina, together with the bride’s personal secretary and many ladies-in-waiting. They travelled in some comfort, their journey assisted – and the bride’s dowry increased – by the pawning of valuables which the Electress Dowager had raided from the Brandenburg state treasury. At Kalmar, not far from the Danish border, they stopped, for here the King himself had come to meet them, pausing en route to purify the land for his bride by torching a number of plague-stricken houses in the surrounding countryside.

At Kalmar, the party passed several days of alternate rest and celebration in the beautiful castle beside its placid harbour. It was an historic place, for here, more than two hundred years before, the triple-Queen Margareta had united Sweden with the neighbouring lands of Norway and a dominant Denmark, a union against which Gustav Adolf’s own grandfather had led his people to rebel.6 Kalmar was Sweden’s architectural jewel, a castle of fairytale beauty and among the finest in Europe, built with a sure artistic sense by the King’s Renaissance forebears. Many of its rooms were beautifully decorated, with painted mouldings and inlaid wood, and finely made furniture from the lands to the south. No doubt it was all displayed with pride to the newcomers, and perhaps, too, the young bride was teased with horror stories of the murders which the same rooms had witnessed, not so very long before.7 If so, they did not deter her. The bridegroom set out for the Tre Kronor Castle, thoughtfully going ahead to give his personal attention to the heating of Maria Eleonora’s rooms, and soon she set out after him with her own entourage on the long, hard journey to Stockholm, 300 miles northward, with the winter closing in around them.

If the sophisticated ambience of Kalmar had reassured the young bride, her composure was soon to be tested as she made her way through her new-found country, for as yet Sweden had little to impress a German countess. Its climate harsh and its people few, it was overwhelmingly rural, with small clusters of farmsteads thinly spread over the less inhospitable southern areas. Lakes and forests dwarfed and isolated all but the largest settlements. Befitting their rural homeland, almost all the Swedes, about a million souls in all, were peasants. A few tens of thousands lived in small and undeveloped towns, and even the nobles mostly chose to live in the countryside, putting their modest incomes back into the land. The very crown revenues, including taxes, were still paid in kind; grain and fish and butter, hides and furs, and iron and copper from Dutch-owned mines, all poured into the royal warehouses, and out of them, too, for the crown’s own servants and even foreign creditors were paid in kind as well. In the early days of Gustav Adolf’s reign, meetings of parliament had taken place in the open air, while at the Tre Kronor Castle, the monarch’s own residence, the doors remained open to all comers.

As the weary train arrived in Stockholm, the young bride’s deepening disappointment turned to dismay. Not yet the country’s formal capital, the grand northern city where she had thought to make her home was in fact scarcely more than a backward country town, its muddy streets lined with basic wooden houses, unwarmed as yet by the ubiquitous red paint that would one day turn their roughness to charm. Goats wandered on the brown turf rooves, nibbling at the roots and grass, sending a plaintive bleating into the chilly air. Inside, the dwellings of rich and poor alike were largely bare, with little covering on the floors and less upon the walls, and now, in the gathering winter, reliably cold. Though the King himself, like his forefathers, was genuinely interested in architecture and the fine arts, there had been little excess wealth for great public buildings or lavish artistic patronage; native literature and music remained rudimentary, theatre almost unknown, paintings and sculpture rare, and Sweden’s nobles, in their bare-walled, bare-floored houses, largely unconvinced. To the citizens of the superbly cultured towns of Italy, or to those of Holland with its advanced financial system and its plethora of cheap goods, Sweden seemed a desperate outpost at the ends of the earth. To Maria Eleonora, accustomed to the rich heritage of Brandenburg and with cultural pretensions of her own, disdain was now added to disappointment. She conceived a contempt for the land and its people, her husband only excepted, and garnered much ill will from her offended new compatriots.