Полная версия:

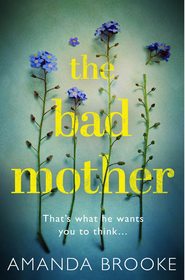

The Bad Mother: The addictive, gripping thriller that will make you question everything

AMANDA BROOKE

The Bad Mother

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Copyright © Amanda Valentine 2017

Cover design by Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photograph © Lyn Randle / Trevillion Images

Amanda Valentine asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008219154

Ebook Edition © December 2017 ISBN: 9780008219161

Version 2017-11-03

Dedication

For Jessica and Nathan

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Amanda Brooke

About the Publisher

Prologue

Coils of copper hair fly across her face, and when she pulls them from her damp cheeks, it feels like ice-cold fingers stroking her skin. She takes a step into the darkness and her foot snags on a tree root threaded through the craggy ledge – or is it another skeletal hand impatient for her fall?

Far below, the night is punctured by a thousand lights that splutter and die where land touches the sea. She’s too far away to detect the salty air washing in from Liverpool Bay, or the urban mix of exhaust fumes and takeaways that remind her of home, but that’s where her thoughts lead her. She follows the dark path of the Mersey and her gaze settles on the sprawling city. She doesn’t dare imagine the pain she is about to inflict on her family.

You can do this, she tells herself.

You have to do this, comes a stronger voice from within. It’s a voice she had all but forgotten since carving her name next to Adam’s on this desolate sandstone ledge. Life had been so full of promise back then. There were a few frayed edges perhaps, but nothing that couldn’t be mended with the love of a good and patient man, or so she had thought. She had realized too late that she had been unravelling and now she was completely undone.

Buffeted by another gust of wind, her summer dress billows out like a parachute and if she dared lean over the precipice, she might see the heavy boughs reaching up, promising to catch her when she falls. They won’t have long to wait.

In the light of a torch, her wedding ring shimmers and unwelcome doubts assail her. If there was another way, she would find it, but even as she tries, her mind spins. The queasy sensation is a familiar one and she knows if she’s not careful, she will lose sight of the path she must take.

‘Lucy.’

Adam’s voice rises above the howling wind as if he has the power to still the night. She knows he will blame himself for this, but there will be enough people to support him after the loss of his beloved wife. She blocks out his voice as she prepares to make the leap, but there’s another voice that cannot be ignored. What mother could fail to respond to the sound of her baby’s cries?

She feels the softness of her daughter’s skin on her lips.

‘Hush,’ she whispers. ‘Mummy’s here.’

1

Six Months Earlier

‘This is a bad idea,’ Christine said as she stood by the garage door watching her daughter battle her way through what amounted to three decades of detritus. ‘Please, come out of there.’

‘I’m fine,’ Lucy said, stepping over the last fingers of light on the concrete floor to immerse herself in the shadows.

Her hip brushed against a sun lounger that hadn’t seen a summer since the noughties when she and her school friends had lazed about in the garden while her mum was at work. They had knocked back blackcurrant alcopops as if they were Ribena, hence the dark vomit stain in the middle of the sagging canvas and the reason it hadn’t been used since.

‘It’s probably not even in there, love.’

‘Judging by how much other junk you’ve kept hold of, I don’t see why not,’ Lucy countered. ‘And I’m sure I remember it being at the back somewhere.’

‘Will you tell her?’ Christine said, turning to the man standing next to her.

Adam stood with his arms folded and his tall, lean frame silhouetted against the cold light of a crisp winter’s morning. When he spoke, the warmth of his words appeared as vaporous swirls above the halo of his dirty blond hair. ‘Your mum has a point. I should be the one in there.’

‘Firstly,’ Lucy said, ‘I know what I’m looking for, and secondly, you’re terrified of spiders.’ She had stopped forcing her way through the junk to face her husband. Sweeping back a coil of copper hair, her emerald-green eyes flashed in defiance and she told herself she would stand her ground even if Adam insisted. To her relief, he didn’t.

‘I tried,’ he said to Christine with a shrug.

Wrapping her Afghan shawl tightly around her shoulders, Christine muttered something under her breath that was unrepeatable. She appeared tiny next to Adam’s six-foot frame, but Lucy’s mum was stronger than she looked. She had brought up her daughter single-handedly since Lucy was eight years old and although the last twenty years hadn’t been easy, what should have broken them had made them stronger and they made a good partnership. They were best friends when they wanted to be, and mother and daughter when it was needed. At that precise moment, Christine’s maternal instincts had kicked in and she wanted to protect her only child.

‘I’ll be careful,’ Lucy called out.

Taking another step into the past, she sized up the gap between an old bedstead and a dressing table. Where once she might have slipped her slender figure through with ease, now she paused to stroke a hand over the slight but firm rise of her belly; her mum wasn’t alone in having a child to protect. Raising herself on to tiptoes, Lucy stretched her long legs so that her bump skimmed the surface of the dresser as she passed.

‘Don’t go wedging yourself in or we’ll never get you out,’ Christine called, before adding, ‘Tell her, Adam.’

‘Don’t forget you’re fat,’ he said, laughing all the more when Lucy scowled.

Christine swiped at her son-in-law. ‘You can’t call a pregnant woman fat, not ever,’ she said, her smile softening the hard stare she was giving him over the rim of her spectacles.

Her mum’s glasses were her only nod to older age. Her spikey dark locks showed no sign of the grey her hairdresser artfully disguised, and her skin glowed from a strict beauty regime. Lucy hoped she would look as good in her fifties, but she had inherited her pale complexion and ginger genes from her dad, so there was no knowing how she would age.

Wiping the dust from her white shirt, Lucy attempted to work out her next move while fearing it was time to admit defeat. Even if she did manage to find what she was looking for, there was no way she would be able to reclaim it without emptying the entire garage. Her mum and dad had moved into their semi-detached house in Liverpool when they had married some thirty years ago, and that was probably the last time anyone had seen the back wall.

Wilfully ignoring her doubts and doubters, Lucy continued on her quest. As she squeezed past a pink metallic bicycle with torn and tattered tassels hanging from its handlebars, it began to move and she put out her hand to stop it from rolling. From the shadows, the orange reflector on the rear wheel shone out like a beacon, drawing her back in time.

She could see her dad kneeling in front of the upturned bike repairing a puncture. He had turned the pedal with his hand so fast that the wheel had become a blur and the reflector transformed into a glowing orange circle. Lucy recalled how her stomach had lurched when the spokes had turned so fast that it looked as if the wheel had magically changed direction. The memory alone made her queasy and threatened to resurrect the morning sickness she hadn’t quite left behind in her first trimester.

‘Can you see anything?’ Adam called.

Lucy had gone as far back as she could reach without taking unnecessary risks. ‘Not yet,’ she said as she peered into the gloom, searching for the faintest suggestion of white painted spindles. It was there somewhere and she wouldn’t leave until she had settled her mind.

‘Seriously, Lucy,’ Adam said. ‘Your mum’s right. It probably isn’t there and if you go any deeper, you don’t know what’s going to fall on top of you. Come out. You’re scaring us.’

‘I’ll be careful,’ she said, not daring to look back. ‘Please, give me one more minute.’

As Lucy swiped at ancient cobwebs covered in dust, a particularly heavy clump clung to her fingers. Shaking it free, she glimpsed the carcass of a giant spider caught by its own web and let out a yelp.

‘Fetch her out, Adam,’ Christine ordered, panic rising in her voice.

There was the creak of furniture being moved and when Lucy turned, she found Adam standing on the other side of the dresser. He had buttoned up his checked shirt to protect his T-shirt and could probably squeeze through the gap at a push but the sight of the dead spider dangling from Lucy’s index finger stopped him in his tracks.

‘Not funny,’ he said.

At thirty-six, Adam was eight years older, but in that moment, he could so easily have been a sulky younger brother. She could still win this argument.

‘Don’t come any nearer,’ she warned.

‘I know why you’re doing this,’ he said, without returning the smile she offered. ‘If you say it’s there, I believe you. And truthfully, do we really want a battered old cot that would probably fail every modern-day health and safety test?’

‘It’s not any old cot, it’s my cot and I’m twenty-eight not fifty-eight. They had health and safety in the nineties too.’

Shaking the dead spider free, Lucy took one last look at the remaining junk. There were boxes piled on top of each other in a leaning tower of decayed cardboard. If Adam were to challenge her, she could describe the contents of each one. They contained her dad’s life, from the manila files kept from the advertising business he ran with his brother, to his sketchpads, his worn-out slippers, and his second-best suit. His best suit had been burnt along with his remains and the picture an eight-year-old Lucy had drawn of him teaching the angels to paint as he had once taught her.

‘It doesn’t matter,’ Adam said. ‘None of this matters.’

Lucy pulled her gaze from the boxes and was about to retrace her steps when something caught her eye. ‘There it is, look!’

The cot had been dismantled and she could see only the two side sections. The wooden spindles were spaced a couple of inches apart and, as Adam had predicted, the wood was splintered and the paint chipped. It wasn’t much of a family heirloom and although her dad had been a gifted artist, the rabbits and squirrels she recalled on the headboard were factory transfers. Her mum was pretty sure they had bought it from Argos.

When Lucy turned, Adam had his lips pursed tightly. She knew what he was thinking and although she wanted to feel vindicated, what she actually felt was foolish. ‘OK, you’re right. I don’t want our baby in some out-of-date deathtrap, and I certainly don’t want to get buried beneath an avalanche of boxes.’

When Adam continued to offer his silent judgement, it was her mum who broke the tension. ‘I don’t know about you two, but I’m freezing out here. Are you leaving it there, or what?’

Lucy reached out for Adam to take her hand but to her horror, he leant backwards. ‘Sorry,’ she gasped, but then followed his gaze and realized how stupid she had been to think, even for a moment, that he was rejecting her. She wiped her hand on her shirt to leave a trail of sticky cobwebs before waggling her fingers. ‘Look, no spiders.’

Adam held her hand as they slipped past the trinkets from her childhood, travelling through her teenage years and towards the most recent additions. There were the stacks of polythene-wrapped canvases she had accumulated at art college, not to mention the camping equipment that had survived several music festivals. A thick layer of dried mud covered the tent she had brought home from Leeds and, with hindsight, it would have been simpler to abandon it, but eighteen months ago she had been unaware that her free and single festival-going days were about to come to an end.

‘Well, that was a waste of time,’ Christine said after returning to the house.

They were huddled in the small galley kitchen that felt cosy rather than cramped, or at least it did to Lucy. Adam had his shoulders hunched, unable to relax in the space that had been exclusive to Lucy and her mum until he had stolen her away.

‘Not a complete waste,’ he said, giving Lucy a wry smile that was warm enough to chase away the chill that had crept into her bones during her ill-conceived search.

With cheekbones a little too sharp and a chin not sharp enough, Adam wasn’t classically handsome, but it had been his pale blue eyes that had captivated Lucy when she had first spied him over the smouldering embers of a barbecue two summers ago. He had looked at her as if he could read her thoughts and then, as now, whatever he saw amused him.

‘Go on, say it,’ he told her.

Lucy pouted. ‘I knew it was there.’

‘And I believed you,’ replied Adam.

‘I could have sworn I’d given it away,’ Christine muttered as she opened the oven door. A cloud of steam rose up to greet her and the smell of rosemary and roasted lamb filled the kitchen. ‘But what was so important about finding it anyway? You obviously didn’t want it.’

‘She was trying to prove a point.’

‘Ah, that’s our Lucy for you,’ Christine said, wiping the steam from her glasses as she crouched down to baste the roast potatoes. ‘I thought you would have worked that out by now, Adam. She likes to be right.’

‘Except when I’m wrong,’ Lucy said, dropping her gaze.

‘But you weren’t wrong,’ Christine said. The light from the oven underlined the confusion on her face as she turned to her daughter. ‘Is there something I’m missing?’

‘I’ve had a few … lapses lately, that’s all.’

Her mum closed the oven door and straightened up. ‘What do you mean, lapses?’

Lucy wasn’t sure how to describe them. They were silly mistakes that might pass unremarked if it were anyone else, but not Lucy. Her brain stored information like a computer and when information went in, it was locked away until it was needed, and she could retrieve it in an instant. She had known precisely where the cot was and she had been proven right. ‘They’re memory lapses, I suppose. I get confused for no reason at all,’ she offered.

Adam cleared his throat. ‘We were late this morning because she couldn’t find her car keys and her car was parked in front of mine so I was blocked in. I found the spare set, but you know what she’s like …’

‘I always leave them on the shelf in the kitchen, or sometimes in my coat pocket, but they weren’t in any of the obvious places,’ Lucy explained. She scrunched up her freckled nose when she added, ‘They were in the fridge beneath a bag of lettuce. I must have kept hold of them when I unloaded the shopping yesterday.’

A bemused smile had formed on Christine’s lips. ‘Welcome to my world,’ she said. ‘I almost put a loaf in the washing machine the other week.’

In no mood to be appeased, Lucy felt the first stirrings of annoyance, not liking that her mum should take the matter so lightly. ‘And do you find things in the wrong place when you have no recollection of moving them?’

Christine took a step nearer until she was close enough to lift Lucy’s chin. ‘No, but I live on my own.’

‘And I work from home, alone. I’m talking about when Adam’s at work.’

‘Have you mentioned it to the midwife?’ Christine asked, looking to Adam.

‘I wanted to raise it at our hospital appointment last week,’ he said, shifting from one foot to the other. ‘But I was overruled.’

Confusion clouded Lucy’s expression and she was grateful that no one was looking at her. She would like to think that she had laid down the law, but Adam was mistaken if he imagined she had been the one to decide against voicing her concerns. It was true that she had been reluctant, but it was Adam who had convinced her that her blunders would be laughed off. So far, he alone knew how unsettling the episodes had become.

‘You still should have mentioned it, Adam,’ Christine said, her smile persisting.

‘I’m glad I didn’t now,’ Lucy grumbled. ‘It was my twenty-week scan and we got to see all her little fingers and toes and I didn’t want to spoil the moment. This memory thing is separate anyway.’

‘Oh, honey, I’m sorry – it’s anything but. They even have a name for it,’ Christine said as she cupped her daughter’s face in the palm of her hand as if she were still her little girl. Her thumb brushed against Lucy’s cheek to encourage a smile that wouldn’t come. ‘It was called baby brain in my day. Though I can’t say I mislaid things, I definitely became a tad scattier. It’s your hormones, that’s all, and I’m afraid it’s only going to get worse. Just wait until you add childbirth and sleepless nights to the mix.’

Lucy’s lip trembled. ‘Baby brain? Really?’

‘Why didn’t you mention it before?’

‘I was scared it was something else,’ Lucy said, holding her mum’s gaze long enough for her to realize at last how frightened she had been. Tears brimmed in her mum’s eyes as she too caught a glimpse of the lingering shadows of the past that had been haunting her daughter.

With a sniff, Christine kissed her daughter’s forehead. ‘You’ve had such a lot of change in the last year or so, it’s no wonder your mind’s playing catch-up. You shouldn’t keep your worries to yourself.’

‘I don’t,’ said Lucy as she pulled away from her mum to look at Adam, who had been waiting patiently to be noticed. Her husband had a habit of tapping his fingers in turn against his thumb whenever he felt out of his comfort zone, and he was doing it now. It was a reminder that beneath that blunt exterior was a man who had his own moments of vulnerability.

Christine wrinkled her nose. ‘I know you have each other but, no offence to Adam, he’s a man.’

‘None taken,’ Adam said. The finger tapping continued.

With her gaze fixed on her daughter, Christine said, ‘I was telling Hannah’s mum the other day how you two girls should make more time for each other now that you’re pregnant. She’s been through it enough times and it would be a shame to let your friendship drift.’

‘I saw her not that long ago,’ Lucy said as she attempted to gauge exactly how long it had been. It was after she had moved in with Adam but before they had scurried off to Greece to get married last summer. ‘It wasn’t long after she had the baby.’

‘He’ll be turning one soon,’ Christine said. ‘I know you both have busy lives, but it would do you good to have someone else to talk to. Don’t you think so, Adam?’

Before Adam could answer, Lucy said, ‘I do love Hannah, but don’t you think she’s a bit chaotic?’ An image of screaming kids and barking dogs came to mind when she added, ‘The boys were all over Adam last time we were there and he ended up spilling coffee all down his shirt.’

‘Lucy was convinced it was deliberate,’ Adam offered.

‘And you weren’t?’ asked Lucy, astonished that Adam should be smiling as if the memory had been a pleasant one. He had tried not to show his annoyance at the time but the atmosphere had turned thick, and Hannah hadn’t helped by making a joke of it, clearly used to such disasters. ‘You couldn’t wait to get out of there, and it was a wonder you didn’t get a speeding ticket on the way home.’

‘I don’t see how I could when it was you driving.’

‘No, it was def—’ she said, stopping herself when she saw the frown forming on Adam’s brow. She could have sworn he had taken the keys from her, but it was so long ago now, maybe she was thinking of a different time. ‘Was it me?’

Adam winced as he looked to Christine. ‘Can you have baby brain before you’re pregnant?’

‘That’s why I think she should talk to Hannah, and New Brighton isn’t that far from you,’ Christine persisted. ‘Apparently she’s another one who thinks you need a visa to get back across the Mersey when you move to the Wirral.’

Lucy didn’t need reminding that she hadn’t seen nearly enough of her family and friends of late, but she had been busy building a new life with Adam. He had to come first and, while she would willingly make the extra effort for her mum, she wasn’t sure if keeping in touch with Hannah was the right thing to do. Feeling slightly wrong-footed, she turned to Adam. ‘I don’t know, what do you think? I could always try to meet up with her without the kids around, and you wouldn’t have to come.’