Полная версия:

Zen in the Art of Writing

Zen in the Art of Writing

Ray Bradbury

HarperVoyager an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk

Published by HarperVoyager 2015

First published in Great Britain by Joshua Odell Editions 1994.

Copyright © 1994 Ray Bradbury Enterprises

Owing to limitations of space, acknowledgements

to reprint may be found on the acknowledgments page.

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Cover images © Shutterstock.com

Ray Bradbury asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008136512

Ebook Edition © May 2015 ISBN: 9780008120870

Version: 2015-04-22

TO MY FINEST TEACHER, JENNET JOHNSON, WITH LOVE

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Preface

HOW TO CLIMB THE TREE OF LIFE, THROW ROCKS AT YOURSELF, AND GET DOWN AGAIN WITHOUT BREAKING YOUR BONES OR YOUR SPIRIT A PREFACE WITH A TITLE NOT MUCH LONGER THAN THE BOOK

THE JOY OF WRITING

RUN FAST, STAND STILL, OR, THE THING AT THE TOP OF THE STAIRS, OR, NEW GHOSTS FROM OLD MINDS

HOW TO KEEP AND FEED A MUSE

DRUNK, AND IN CHARGE OF A BICYCLE

INVESTING DIMES: FAHRENHEIT 451

JUST THIS SIDE OF BYZANTIUM: DANDELION WINE

THE LONG ROAD TO MARS

ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS

THE SECRET MIND

SHOOTING HAIKU IN A BARREL

ZEN IN THE ART OF WRITING

…ON CREATIVITY

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Ray Bradbury

About the Publisher

Preface

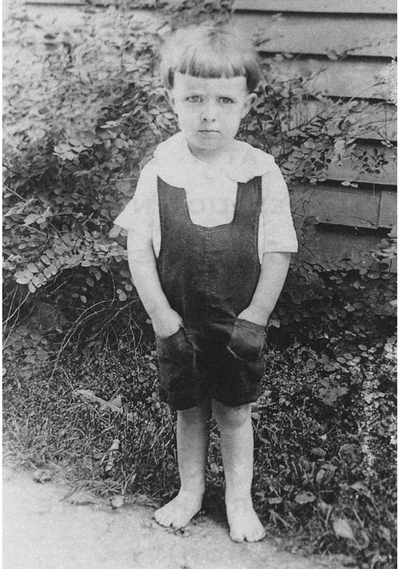

The Author-In-Residence

Green Town, Illinois, 1923

HOW TO CLIMB THE TREE OF LIFE, THROW ROCKS AT YOURSELF, AND GET DOWN AGAIN WITHOUT BREAKING YOUR BONES OR YOUR SPIRIT A PREFACE WITH A TITLE NOT MUCH LONGER THAN THE BOOK

Sometimes I am stunned at my capacity as a nine-year-old, to understand my entrapment and escape it.

How is it that the boy I was in October, 1929, could, because of the criticism of his fourth grade schoolmates, tear up his Buck Rogers comic strips and a month later judge all of his friends idiots and rush back to collecting?

Where did that judgment and strength come from? What sort of process did I experience to enable me to say: I am as good as dead. Who is killing me? What do I suffer from? What’s the cure?

I was able, obviously, to answer all of the above. I named the sickness: my tearing up the strips. I found the cure: go back to collecting, no matter what.

I did. And was made well.

But still. At that age? When we are accustomed to responding to peer pressure?

Where did I find the courage to rebel, change my life, live alone?

I don’t want to over-estimate all this, but damn it, I love that nine-year-old, whoever in hell he was. Without him, I could not have survived to introduce these essays.

Part of the answer, of course, is in the fact that I was so madly in love with Buck Rogers, I could not see my love, my hero, my life, destroyed. It is almost that simple. It was like having your best all-round greatest-loving-buddy, pal, center-of-life drown or get shotgun killed. Friends, so killed, cannot be saved from funerals. Buck Rogers, I realized, might know a second life, if I gave it to him. So I breathed in his mouth and, lo!, he sat up and talked and said, what?

Yell. Jump. Play. Out-run those sons-of-bitches. They’ll never live the way you live. Go do it.

Except I never used the S.O.B. words. They were not allowed. Heck! was about the size and strength of my outcry. Stay alive!

So I collected comics, fell in love with carnivals and World’s Fairs and began to write. And what, you ask, does writing teach us?

First and foremost, it reminds us that we are alive and that it is a gift and a privilege, not a right. We must earn life once it has been awarded us. Life asks for rewards back because it has favored us with animation.

So while our art cannot, as we wish it could, save us from wars, privation, envy, greed, old age, or death, it can revitalize us amidst it all.

Secondly, writing is survival. Any art, any good work, of course, is that.

Not to write, for many of us, is to die.

We must take arms each and every day, perhaps knowing that the battle cannot be entirely won, but fight we must, if only a gentle bout. The smallest effort to win means, at the end of each day, a sort of victory. Remember that pianist who said that if he did not practice every day he would know, if he did not practice for two days, the critics would know, after three days, his audiences would know.

A variation of this is true for writers. Not that your style, whatever that is, would melt out of shape in those few days.

But what would happen is that the world would catch up with and try to sicken you. If you did not write every day, the poisons would accumulate and you would begin to die, or act crazy, or both.

You must stay drunk on writing so reality cannot destroy you.

For writing allows just the proper recipes of truth, life, reality as you are able to eat, drink, and digest without hyperventilating and flopping like a dead fish in your bed.

I have learned, on my journeys, that if I let a day go by without writing, I grow uneasy. Two days and I am in tremor. Three and I suspect lunacy. Four and I might as well be a hog, suffering the flux in a wallow. An hour’s writing is tonic. I’m on my feet, running in circles, and yelling for a clean pair of spats.

So that, in one way or another, is what this book is all about.

Taking your pinch of arsenic every morn so you can survive to sunset. Another pinch at sunset so that you can more-than-survive until dawn.

The micro-arsenic-dose swallowed here prepares you not to be poisoned and destroyed up ahead.

Work in the midst of life is that dosage. To manipulate life, toss the bright-colored orbs up to mix with the dark ones, blending a variation of truths. We use the grand and beautiful facts of existence in order to put up with the horrors that afflict us directly in our families and friends, or through the newspapers and T.V.

The horrors are not to be denied. Who amongst us has not had a cancer-dead friend? Which family exists where some relative has not been killed or maimed by the automobile? I know of none. In my own circle, an aunt, and uncle, and a cousin, as well as six friends, have been destroyed by the car. The list is endless and crushing if we do not creatively oppose it.

Which means writing as cure. Not completely, of course. You never get over your parents in the hospital or your best love in the grave.

I won’t use the word ‘therapy,’ it’s too clean, too sterile a word. I only say when death slows others, you must leap to set up your diving board and dive head first into your typewriter.

The poets and artists of other years, long past, knew all and everything I have said here, or put in the following essays. Aristotle said it for the ages. Have you listened to him lately?

These essays were written at various times over a thirty-year period, to express special discoveries, to serve special needs. But they all echo the same truths of explosive self-revelation and continuous astonishment at what your deep well contains if you just haul off and shout down it.

Even as I write this, a letter has come from a young, unknown writer, who says he is going to live by my motto, found in my Toynbee Convector.

‘…to gently lie and prove the lie true…everything is finally a promise…what seems a lie is a ramshackle need, wishing to be born.…’

And now:

I have come up with a new simile to describe myself lately. It can be yours.

Every morning I jump out of bed and step on a landmine. The landmine is me.

After the explosion, I spend the rest of the day putting the pieces together.

Now, it’s your turn. Jump!

THE JOY OF WRITING

Zest. Gusto. How rarely one hears these words used. How rarely do we see people living, or for that matter, creating by them. Yet if I were asked to name the most important items in a writer’s make-up, the things that shape his material and rush him along the road to where he wants to go, I could only warn him to look to his zest, see to his gusto.

You have your list of favorite writers; I have mine. Dickens, Twain, Wolfe, Peacock, Shaw, Molière, Jonson, Wycherly, Sam Johnson. Poets: Gerard Manley Hopkins, Dylan Thomas, Pope. Painters: El Greco, Tintoretto. Musicians: Mozart, Haydn, Ravel, Johann Strauss (!). Think of all these names and you think of big or little, but nonetheless important, zests, appetites, hungers. Think of Shakespeare and Melville and you think of thunder, lightning, wind. They all knew the joy of creating in large or small forms, on unlimited or restricted canvasses. These are the children of the gods. They knew fun in their work. No matter if creation came hard here and there along the way, or what illnesses and tragedies touched their most private lives. The important things are those passed down to us from their hands and minds and these are full to bursting with animal vigor and intellectual vitality. Their hatreds and despairs were reported with a kind of love.

Look at El Greco’s elongation and tell me, if you can, that he had no joy in his work? Can you really pretend that Tintoretto’s God Creating the Animals of the Universe is a work founded on anything less than ‘fun’ in its widest and most completely involved sense? The best jazz says, ‘Gonna live forever; don’t believe in death.’ The best sculpture, like the head of Nefertiti, says again and again, ‘The Beautiful One was here, is here, and will be here, forever.’ Each of the men I have listed seized a bit of the quicksilver of life, froze it for all time and turned, in the blaze of their creativity, to point at it and cry, ‘Isn’t this good!’ And it was good.

What has all this to do with writing the short story in our times?

Only this: if you are writing without zest, without gusto, without love, without fun, you are only half a writer. It means you are so busy keeping one eye on the commercial market, or one ear peeled for the avant-garde coterie, that you are not being yourself. You don’t even know yourself. For the first thing a writer should be is – excited. He should be a thing of fevers and enthusiasms. Without such vigor, he might as well be out picking peaches or digging ditches; God knows it’d be better for his health.

How long has it been since you wrote a story where your real love or your real hatred somehow got onto the paper? When was the last time you dared release a cherished prejudice so it slammed the page like a lightning bolt? What are the best things and the worst things in your life, and when are you going to get around to whispering or shouting them?

Wouldn’t it be wonderful, for instance, to throw down a copy of Harper’s Bazaar you happened to be leafing through at the dentist’s, and leap to your typewriter and ride off with hilarious anger, attacking their silly and sometimes shocking snobbishness? Years ago I did just that. I came across an issue where the Bazaar photographers, with their perverted sense of equality, once again utilized natives in a Puerto Rican backstreet as props in front of which their starved-looking mannikins postured for the benefit of yet more emaciated half-women in the best salons in the country. The photographs so enraged me I ran, did not walk, to my machine and wrote ‘Sun and Shadow’, the story of an old Puerto Rican who ruins the Bazaar photographer’s afternoon by sneaking into each picture and dropping his pants.

I dare say there are a few of you who would like to have done this job. I had the fun of doing it; the cleansing after effects of the hoot, the holler, and the great horselaugh. Probably the editors at the Bazaar never heard. But a lot of readers did and cried, ‘Go it, Bazaar, go it, Bradbury!’ I claim no victory. But there was blood on my gloves when I hung them up.

When was the last time you did a story like that, out of pure indignation?

When was the last time you were stopped by the police in your neighborhood because you like to walk, and perhaps think, at night? It happened to me just often enough that, irritated, I wrote ‘The Pedestrian’, a story of a time, fifty years from now, when a man is arrested and taken off for clinical study because he insists on looking at un-televised reality, and breathing un-air-conditioned air.

Irritations and angers aside, what about loves? What do you love most in the world? The big and little things, I mean. A trolley car, a pair of tennis shoes? These, at one time when we were children, were invested with magic for us. During the past year I’ve published one story about a boy’s last ride in a trolley that smells of all the thunderstorms in time, full of cool-green moss-velvet seats and blue electricity, but doomed to be replaced by the more prosaic, more practical-smelling bus. Another story concerned a boy who wanted to own a pair of new tennis shoes for the power they gave him to leap rivers and houses and streets, and even bushes, sidewalks, and dogs. The shoes were to him, the surge of antelope and gazelle on African summer veldt. The energy of unleashed rivers and summer storms lay in the shoes; he had to have them more than anything else in the world.

So, simply then, here is my formula.

What do you want more than anything else in the world? What do you love, or what do you hate?

Find a character, like yourself, who will want something or not want something, with all his heart. Give him running orders. Shoot him off. Then follow as fast as you can go. The character, in his great love, or hate, will rush you through to the end of the story. The zest and gusto of his need, and there is zest in hate as well as in love, will fire the landscape and raise the temperature of your typewriter thirty degrees.

All of this is primarily directed to the writer who has already learned his trade; that is, has put into himself enough grammatical tools and literary knowledge so he won’t trip himself up when he wants to run. The advice holds good for the beginner, too, however, even though his steps may falter for purely technical reasons. Even here, passion often saves the day.

The history of each story, then, should read almost like a weather report: Hot today, cool tomorrow. This afternoon, burn down the house. Tomorrow, pour cold critical water upon the simmering coals. Time enough to think and cut and rewrite tomorrow. But today – explode – fly apart – disintegrate! The other six or seven drafts are going to be pure torture. So why not enjoy the first draft, in the hope that your joy will seek and find others in the world who, reading your story, will catch fire, too?

It doesn’t have to be a big fire. A small blaze, candlelight perhaps; a longing for a mechanical wonder like a trolley or an animal wonder like a pair of sneakers rabbiting the lawns of early morning. Look for the little loves, find and shape the little bitternesses. Savor them in your mouth, try them on your typewriter. When did you last read a book of poetry or take time, of an afternoon, for an essay or two? Have you ever read a single issue of Geriatrics, the Official Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, a magazine devoted to ‘research and clinical study of the diseases and processes of the aged and aging’? Or read, or even seen, a copy of What’s New, a magazine published by the Abbott Laboratories in North Chicago, containing articles such as ‘Tubocurarene for Cesarean Section’ or ‘Phenurone in Epilepsy’, but also utilizing poems by William Carlos Williams, Archibald Macleish, stories by Clifton Fadiman and Leo Rosten; covers and interior illustrations by John Groth, Aaron Bohrod, William Sharp, Russell Cowles? Absurd? Perhaps. But ideas lie everywhere, like apples fallen and melting in the grass for lack of wayfaring strangers with an eye and a tongue for beauty, whether absurd, horrific, or genteel.

Gerard Manley Hopkins put it this way:

Glory be to God for dappled things—

For skies of couple-color as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced—fold, fallow, and plow;

And all trades, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise Him.

Thomas Wolfe ate the world and vomited lava. Dickens dined at a different table every hour of his life. Molière, tasting society, turned to pick up his scalpel, as did Pope and Shaw. Everywhere you look in the literary cosmos, the great ones are busy loving and hating. Have you given up this primary business as obsolete in your own writing? What fun you are missing, then. The fun of anger and disillusion, the fun of loving and being loved, of moving and being moved by this masked ball which dances us from cradle to churchyard. Life is short, misery sure, mortality certain. But on the way, in your work, why not carry those two inflated pig-bladders labeled Zest and Gusto. With them, traveling to the grave, I intend to slap some dummox’s behind, pat a pretty girl’s coiffure, wave to a tad up a persimmon tree.

Anyone wants to join me, there’s plenty of room in Coxie’s Army.

1973

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги

Всего 10 форматов