Полная версия:

Hold the Dream

BARBARA TAYLOR BRADFORD

Hold the Dream

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This paperback edition 2004

First published in paperback by Grafton 1986

First published in Great Britain by Granada Publishing 1985

Copyright © Barbara Taylor Bradford 1985

Barbara Taylor Bradford asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780586058497

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2014 ISBN: 9780007363698

Version: 2018-11-08

Dedication

For Bob – who makes everything possible

for me, with my love.

Epigraph

‘She possessed, in the highest degree,

all the qualities which were required in a

great Prince.’

GIOVANNI SCARAMELLI,

Venetian Ambassador

to the Court of Elizabeth Tudor,

Queen of England

‘I would have you know that this kingdom

of mine is not so scant of men but there be

a rogue or two among them.’

ELIZABETH TUDOR, Queen of England

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

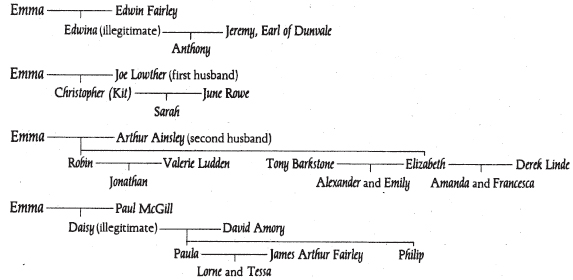

Family Tree

Book One: Matriarch

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Book Two: Heiress

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Book Three: Tycoon

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Keep Reading

About the Author

Other Books By

About the Publisher

Family Tree (Emma Harte)

Matriarch

‘I speak the truth, not so much as I

would, but as much as I dare; and

I dare a little more, as I grow older.’

MONTAIGNE

CHAPTER 1

Emma Harte was almost eighty years old.

She did not look it, for she had always carried her years lightly. Certainly Emma felt like a much younger woman as she sat at her desk in the upstairs parlour of Pennistone Royal on this bright April morning of 1969.

Her posture was erect in the chair, and her alert green eyes, wise and shrewd under the wrinkled lids, missed nothing. The burnished red-gold hair had turned to shining silver long ago, but it was impeccably coiffed in the latest style, and the widow’s peak was as dramatic as ever above her oval face. If this was now lined and scored by the years, her excellent bone structure had retained its clarity and her skin held the translucency of her youth. And so, though her great beauty had been blurred by the passage of time, she was still arresting, and her appearance, as always, was stylish.

For the busy working day stretching ahead of her she had chosen to wear a woollen dress of tailored simplicity in the powder-blue shade she so often favoured, and which was so flattering to her. A frothy white lace collar added just the right touch of softness and femininity at her throat, and there were discreet diamond studs on her ears. Otherwise she wore no jewellery, except for a gold watch and her rings.

After her bout with bronchial pneumonia the previous year she was in blooming health, had no infirmities to speak of, and she was filled with the restless vigour and drive that had marked her younger days.

That’s my problem, not knowing where to direct all this damned energy, she mused, putting down her pen, leaning back in the chair. She smiled and thought: The devil usually finds work for idle hands, so I’d better come up with a new project soon before I get into mischief. Her smile widened. Most people thought she had more than enough to keep her fully occupied, since she continued to control her vast business enterprises which stretched halfway round the world. Indeed, they did need her constant supervision; yet, for the most part, they offered her little challenge these days. Emma had always thrived on challenge, and it was this she sorely missed. Playing watchdog was not particularly exciting to her way of thinking. It did not fire her imagination, bring a tingle to her blood, or get her adrenaline flowing in the same way that wheeling and dealing did. Pitting her wits against business adversaries, and striving for power and supremacy in the international marketplace, had become such second nature to her over the years they were now essential to her well-being.

Restlessly she rose, crossed the floor in swift light steps, and opened one of the soaring leaded windows. She took a deep breath, peered out. The sky was a faultless blue, without a single cloud, and radiant with spring sunshine. New buds, tenderly green, sprouted on the skeletal branches, and under the great oak at the edge of the lawn a mass of daffodils, randomly planted, tossed yellow-bright heads under the fluttering breeze.

‘I wandered lonely as a cloud that floats on high o’er vale and hill, when all at once I saw a crowd, a host of golden daffodils,’ she recited aloud, then thought: Good heavens, I learned that Wordsworth poem at the village school in Fairley. So long ago, and to think that I’ve remembered it all these years.

Raising her hand, she closed the window, and the great McGill emerald on the third finger of her left hand flashed as the clear Northern light struck the stone. Its brilliance caught her attention. She had worn this ring for forty-four years, ever since that day, in May of 1925, when Paul McGill had placed it on her finger. He had thrown away her wedding ring, symbol of her disastrous marriage to Arthur Ainsley, then slipped on the massive square-cut emerald. ‘We might not have had the benefit of clergy,’ Paul had said that memorable day. ‘But as far as I’m concerned, you are my wife. From this day forward until death do us part.’

The previous morning their child had been born. Their adored Daisy, conceived in love and raised with love. Her favourite of all her children, just as Paula, Daisy’s daughter, was her favourite grandchild, heiress to her enormous retailing empire and half of the colossal McGill fortune which Emma had inherited after Paul’s death in 1939. And Paula had given birth to twins four weeks ago, had presented her with her first great-grandchildren, who tomorrow would be christened at the ancient church in Fairley village.

Emma pursed her lips, suddenly wondering if she had made a mistake in acquiescing to this wish of Paula’s husband, Jim Fairley. Jim was a traditionalist, and thus wanted his children to be christened at the font where all of the Fairleys had been baptized, and all of the Hartes for that matter, herself included.

Oh well, she thought, I can’t very well renege at this late date, and perhaps it is only fitting. She had wreaked her revenge on the Fairleys, the vendetta she had waged against them for most of her life was finally at an end, and the two families had been united through Paula’s marriage with James Arthur Fairley, the last of the old line. It was a new beginning.

But when Blackie O’Neill had heard of the choice of church he had raised a snowy brow and chuckled and made a remark about the cynic turning into a sentimentalist in her old age, an accusation he was frequently levelling at her of late. Maybe Blackie was right in this assumption. On the other hand, the past no longer troubled her as it once had. The past had been buried with the dead. Only the future concerned her now. And Paula and Jim and their children were that future.

Emma’s thoughts centred on Fairley village as she returned to her desk, put on her glasses and stared at the memorandum in front of her. It was from her grandson Alexander, who, with her son Kit, ran her mills, and it was bluntly to the point, in Alexander’s inimitable fashion. The Fairley mill was in serious trouble. It had been failing to break even for the longest time and was now deeply in the red. A crucial decision hovered over her head … to close the mill or keep it running at a considerable loss. Emma, ever the pragmatist, knew deep in her bones that the wisest move would be to close down the Fairley operation, yet she balked at this drastic measure, not wanting to bring hardship to the village of her birth. She had asked Alexander to find an alternative, a workable solution, hoped that he had done so. She would soon know. He was due to arrive for a meeting with her imminently.

One possibility which might enable them to resolve the situation at the Fairley mill had occurred to Emma, but she wanted to give Alexander his head, an opportunity to handle this problem himself. Testing him, she admitted, as I’m constantly testing all of my grandchildren. And why not? That was her prerogative, wasn’t it? Everything she owned had been hard won, built on a life rooted in single-mindedness of purpose and the most gruelling work and dogged determination and relentlessness and terrible sacrifice. Nothing had ever been handed to her on a plate. Her mighty empire was entirely of her own making, and, since it was hers and hers alone, she could dispose of it as she wished.

And so with calm deliberation and judiciousness and selectivity she had chosen her heirs one year ago, bypassing four of her five children in favour of her grandchildren in the new will she had drawn; yet she continued to scrutinize the third generation, forever evaluating their worth, seeking weaknesses in them whilst inwardly praying to find none.

They have lived up to my expectations, she reassured herself, then thought with a swift stab of dismay: No, that’s not strictly true. There is one of whom I am not really sure, one whom I don’t think I can trust.

Emma unlocked the top drawer of her desk, took out a sheet of paper, and studied the names of her grandchildren, which she had listed only last night when she had experienced her first feelings of uneasiness. Is there a joker in this pack, as I suspect? she asked herself worriedly, squinting at the names. And if there is, how on earth will I handle it?

Her eyes remained riveted to one name. She shook her head, with sadness, pondering.

Treachery had long ceased to surprise Emma, for her natural astuteness and psychological insight had been sharply honed during a long, frequently hard, and always extraordinary life. In fact, relatively few things surprised her any more, and, with her special brand of cynicism, she had come to expect the worst from people, including family. Yet she had been taken aback last year when she had discovered through Gaye Sloane, her secretary, that her four eldest children were wilfully plotting against her. Spurred on by their avariciousness and vaunting ambition, they had endeavoured to wrest her empire away from her in the most underhanded way, seriously underestimating her in the process. Her initial shock, and the pain of betrayal, had been swiftly replaced by an anger of icy ferocity, and she had made her moves with speed and consummate skill and resourcefulness, which was her way when facing any opponent. And she had pushed sentiment and emotions aside, had not allowed feelings to obscure intelligence, for it was her superior intelligence which had inevitably saved her in disastrous situations in the past.

If she had outwitted the inept plotters, had left them floundering stupidly in disarray, she had also finally come to the bitter, and chilling, realization that blood was not thicker than water. It had struck her, and most forcibly, that ties of the blood and of the flesh did not come into play when vast amounts of money and, more importantly, great power, were at stake. People thought nothing of killing to attain even the smallest portions of both. Despite her overriding disgust and disillusionment with her children, she had been very sure of their children, their devotion to her. Now one of them was causing her to re-evaluate her judgement and question her trust.

She turned the name over in her mind … Perhaps she was wrong; she hoped she was wrong. She had nothing to go on really – except gut instinct and her prescience. But, like her intelligence, both had served her well throughout her life.

Always when she faced this kind of dilemma, Emma’s instinctive attitude was to wait – and watch. Once again she decided to play for time. By doing thus she could conceal her real feelings, whilst gambling that things would sort themselves out to her advantage, thereby dispensing with the need for harsh action. But I will dole out the rope, she added inwardly. Experience had taught her that when lots of freely proffered rope fell into unwitting hands it invariably formed a noose.

Emma considered the manifold possibilities if this should happen, and a hard grimness settled over her face and her eyes darkened. She did not relish picking up the sword again, to defend herself and her interests, not to mention her other heirs.

History does have a way of repeating itself, she thought wearily, especially in my life. But I refuse to anticipate. That’s surely borrowing trouble. Purposefully, she put the list back in the drawer, locked it, and pocketed the key.

Emma Harte had the enviable knack of shelving unsolvable problems in order to concentrate on priorities, and so she was enabled to subdue the nagging – and disturbing – suspicion that a grandchild of hers was untrustworthy, and therefore a potential adversary. Current business was the immediate imperative, and she gave her attention to her appointments for the rest of the day, each of which was with three of the six grandchildren who worked for her.

Alexander would come first.

Emma glanced at her watch. He was due to arrive in fifteen minutes, at ten-thirty. He would be on time, if not indeed early. Her lips twitched in amusement. Alexander had become something of a demon about punctuality, he had even chided her last week when she had kept him waiting, and he was forever at odds with his mother, who suffered from a chronic disregard for the clock. Her amused smile fled, was replaced by a cold and disapproving tightness around her mouth as she contemplated her second daughter.

Elizabeth was beginning to push her patience to the limits – gallivanting around the world in the most scandalous manner, marrying and divorcing haphazardly, and with such increasing frequency it was appalling. Her daughter’s inconsistency and instability had ceased to baffle her, for she had long understood that Elizabeth had inherited most of her father’s worst traits. Arthur Ainsley had been a weak, selfish and self-indulgent man; these flaws were paramount in his daughter, and following his pattern, the beautiful, wild and wilful Elizabeth flouted all the rules, and had remained untamed. And dreadfully unhappy, Emma acknowledged to herself. The woman has become a tragic spectacle, to be pitied, perhaps, rather than condemned.

She wondered where her daughter was at the moment, then instantly dropped the thought. It was of no consequence, she supposed, since they were barely on speaking terms after the matter of the will. Surprisingly, even Alexander had been treated to a degree of cold-shouldering by his adoring mother because he had been favoured in her place. But Elizabeth had not been able to cope with Alexander’s cool indifference to her feelings, and her hysterical tantrums and the rivers of tears had abruptly ceased when she realized she was wasting her time. She had capitulated in the face of his aloofness, disapproval, and thinly-veiled contempt. Her son’s good opinion of her, and his love, were vital, apparently, and she had made her peace with him, mended her ways. But not for long, Emma thought acidly. She soon fell back into her bad habits. And it’s certainly no thanks to that foolish and skittish woman that Alexander has turned out so well.

Emma experienced a little rush of warmth mingled with gratification as she contemplated her grandson. Alexander had become the man he was because of his strength of character and his integrity. He was solid, hardworking, dependable. If he did not have his cousin Paula’s brilliance, and lacked her vision in business, he was, nonetheless, sound of judgement. His conservative streak was balanced by a degree of flexibility, and he displayed a genuine willingness to weigh the pros and cons of any given situation, and, when necessary, make compromises. Alexander had the ability to keep everything in its proper perspective, and this was reassuring to Emma, who was a born realist herself.

This past year Alexander had proved himself deserving of her faith in him, and she had no regrets about making him the chief heir to Harte Enterprises by leaving him fifty-two per cent of her shares in this privately-held company. Whilst he continued to supervise the mills, she deemed it essential for him to have a true understanding of every aspect of the holding corporation, and she had been training him assiduously, preparing him for the day when he took over the reins from her.

Harte Enterprises controlled her woollen mills, clothing factories, real estate, the General Retail Trading Company, and the Yorkshire Consolidated Newspaper Company, and it was worth many millions of pounds. She had long recognized that Alexander might never increase its worth by much, because of his tendency to be cautious; but, for the same reason, neither would he ruin it through rash decisions and reckless speculation. He would keep it on the steady course she had so carefully charted, following the guidelines and principles she had set down years ago. This was the way she wanted it, had planned it, in point of fact.

Emma drew her appointment book towards her, and checked the time of her lunch with Emily, Alexander’s sister.

Emily was due to arrive at one o’clock.

When she had phoned earlier in the week Emily had sounded somewhat enigmatic when she had said she had a serious problem to discuss. There was no mystery, as far as Emma was concerned. She knew what Emily’s problem was, had known about it for a long time. She was only surprised her granddaughter had not asked to discuss it before now. She lifted her head and stared into space reflectively, turning the matter over in her mind, and then she frowned. Two weeks ago she had come to a decision about Emily, and she was convinced it was the right one. But would Emily agree? Yes, she answered herself. The girl will see the sense in it, I’m positive of that. Emma brought her eyes back to the open page of the diary.

Paula would stop by at the end of the afternoon.

She and Paula were to discuss the Cross project. Now, if that is skilfully handled by Paula, and she brings the negotiations to a favourable conclusion, then I’ll have the challenge I’m looking for, Emma thought. Her mouth settled into its familiar resolute lines as she turned her attention to the balance sheets of the Aire Communications Company, owned, by the Crosses. The figures were disastrous – and damning. But its financial problems aside, the company was weighted down with serious afflictions of such enormity they boggled the mind. According to Paula, these could be surmounted and solved, and she had evolved a plan so simple yet so masterful in its premise, Emma had been both intrigued and impressed.

‘Let’s buy the company, Grandy,’ Paula had said to her a few weeks ago. ‘I realize Aire looks like a catastrophe, and actually it is, but only because of its bad management, and its present structure. It’s a hodgepodge. Too diversified. And they have too many divisions. Those that make a good profit can never get properly ahead and really flourish because they’re burdened by the divisions which are in the red, and which they have to support.’ Paula had then walked her through the plan, step by step, and Emma had instantly understood how Aire Communications could be turned round and in no time at all. She had instructed her granddaughter to start negotiating immediately.

How she would love to get her hands on that little enterprise. And perhaps she would, and very soon too, if her reading of the situation was as accurate as she thought. Emma was convinced that no one was better equipped to deal with John Cross and his son, Sebastian, than Paula, who had developed into a tough and shrewd negotiator. She no longer equivocated when Emma hurled her into touchy business situations that required nimble thinking and business acumen, which she possessed in good measure. And of late her self-confidence had grown.

Emma glanced at her watch again, then curbed the impulse to telephone Paula at the store in Leeds, to give her a few last-minute tips about John Cross and how to deal with him effectively. Paula had proved she had come into her own, and Emma did not want her to think she was forever breathing down her neck.