Полная версия:

Shadow on the Crown

Copyright

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2013

Copyright © Patricia Bracewell 2013

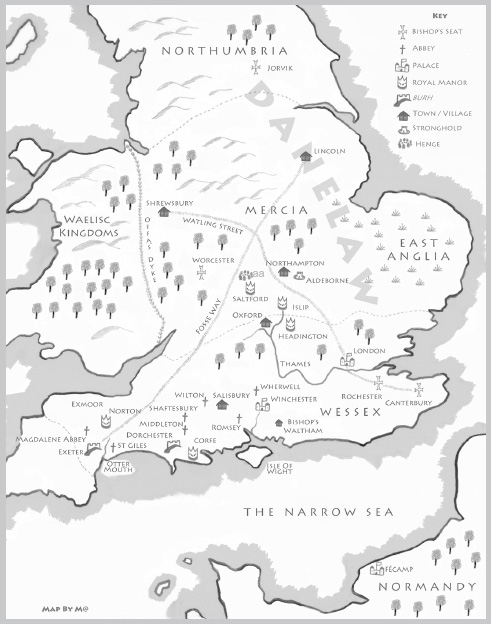

Map © Matt Brown 2013

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Cover photography © Richard Jenkins

Patricia Bracewell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007481767

Ebook Edition © 2014 ISBN: 9780007481750

Version: 2015-09-29

For Lloyd, Andrew, and Alan

The English Court, 1001–1005

Æthelred II, Anglo-Saxon king of England

Children of the English king, in birth order:

Athelstan

Ecbert

Edmund

Edrid

Edwig

Edward

Edgar

Edyth

Ælfgifu (Ælfa)

Wulfhilde (Wulfa)

Mathilda

Leading Nobles and Ecclesiastics

Ælfhelm, ealdorman of Northumbria

Ufegeat, his son

Wulfheah, his son (Wulf)

Elgiva, his daughter

Ælfric, ealdorman of Hampshire

Ælfgar, his son

Hilde, his granddaughter

Ælfheah, bishop of Winchester

Godwine, ealdorman of Lindsey

Leofwine, ealdorman of Western Mercia

Wulfstan, archbishop of Jorvik and bishop of Worcester

The Norman Court, 1001–1005

Richard II, duke of Normandy

Robert, archbishop of Rouen, brother of the duke

Judith, duchess of Normandy

Gunnora, dowager duchess of Normandy

Mathilde, sister of the duke

Emma, sister of the duke

The Danish Royals

Swein Forkbeard, king of Denmark

Harald, his son

Cnut, his son

A.D. 978 In this year was King Edward slain at even-tide, at Corfe-gate, on the fifteenth before the kalends of April, and he was buried at Werham without any royal honours. Nor was a worse deed than this done since men came to Britain … Æthelred was consecrated king. In this same year a bloody sky was often seen, most clearly at midnight, like fire in the form of misty beams. As dawn approached, it glided away.

– The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Map

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Author’s Note

Glossary

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Eve of St Hilda’s Feast, November 1001

Near Saltford, Oxfordshire

She made a circuit of the clearing among the oaks, three times round and three times back, whispering spells of protection. There had been a portent in the night: a curtain of red light had shimmered and danced across the midnight sky like scarlet silk flung against the stars. Once, in the year before her birth, such a light had marked a royal death. Now it surely marked another, and although her magic could not banish death, she wove the spells to ward disaster from the realm.

When her task was done she fed the fire that burned in the centre of the ancient stone ring, and sitting down beside it, she waited for the one who came in search of prophecy. Before the sun had moved a finger’s width across the sky, the figure of a woman, cloaked and veiled, stood atop the rise, her hand upon the sentinel stone. Slowly she followed the path down through the trees and into the giants’ dance until she, too, took her place beside the fire, with silver in her palm.

‘I would know my lady’s fate,’ she said.

The silver went from hand to hand, and against her will, the seer glimpsed a heart, broken and barren, that loved with a dark and twisted love. But the silver had been given, and at her nod, a lock of hair was laid upon the flames. She searched for visions in the fire, and they tumbled and roiled until they hurt her eyes and scored her heart.

‘Your lady will be bound to a mighty lord,’ she said at last, ‘and her children will be kings.’

But because of the darkness in that heart across the fire, she said nothing of the other, of the Lady who would journey from afar, and of the two life threads so knotted and tangled that they could not be pulled asunder for a lifetime or for ever. She did not speak of the green land that would burn to ash in the days to come, nor of the innocents who would die, all for the price of a throne.

There would be portents in the sky again tonight, she knew, and high above her the stars would weep blood.

A.D. 1001 This year there was great commotion in England in consequence of an invasion by the Danes, who spread terror and devastation wheresoever they went, plundering and burning and desolating the country … They brought much booty with them to their ships, and thence they went into the Isle of Wight and nothing withstood them; nor any fleet by sea durst meet them; nor land force either. Then was it in every wise a heavy time, because they never ceased from their evil doings.

– The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

24th December 1001

Fécamp, Normandy

The winter of 1001 in northwestern Europe would have been recorded as the coldest and fiercest in seventy-five years, had anyone been keeping such records. In late December of that year, a storm tore out of the arctic north with terrible speed, blasting all of Europe but striking hardest at the two realms that faced each other across the Narrow Sea.

In Normandy, it began with a sudden drop in temperature and a freezing rain that coated the limbs of the precious fruit trees in the Seine’s fertile valley. A driving wind swept behind the rain, snapping brittle, frozen branches and scattering the promise of next summer’s harvest over wide, sleet-covered fields. For a full day and night the storm raged, and when the worst of it was spent, a light snow fell upon the wasted landscape as quietly as a benediction.

Watching from within their abbey walls, the monks of Jumièges and of Saint-Wandrille contemplated the loss of their apple crop, bowed their heads, and prayed for acceptance of God’s will. Peasant farmers, huddling together for warmth in frail, wooden cottages and fearing that the end of the world was come, prayed for deliverance. In the newly built ducal palace at Fécamp, where Duke Richard and his family had gathered to celebrate the season of Christ’s Mass, the duke’s fifteen-year-old sister, Emma, quietly pulled heavy boots over her thick woollen leggings and prayed that she would not waken her sleeping sister – to no avail.

‘What are you doing?’ Mathilde’s voice, raw and resonating with elder sister disapproval, emerged from a thick nest of bedclothes.

Emma continued to tug at a boot.

‘I am going down to the stables,’ she said.

She threw her sister a sidelong glance, trying to gauge her mood. Mathilde’s thin brown hair was pulled into a tight braid that gave her face a drawn, pinched look and added to the severity of the frown that she cast upon her younger sister.

‘You cannot go out in this storm,’ Mathilde protested. ‘You will catch your death.’ She started to say more but was racked by a sudden, cruel fit of coughing.

Emma went to her, snatched up the cup of watered wine from a table beside the bed, and held it for her sister to drink.

‘The snow has stopped,’ she said, as Mathilde sipped from the cup. ‘I will be fine.’

And unlike Mathilde, Emma thought to herself, she rarely took sick. Poor Mathilde. It was her misfortune to be the only small, dark-haired, sickly child in her mother’s brood of blond, vigorous giants – eight brothers and sisters, all told.

When her sister had drunk her fill, Emma snatched up a shawl from the foot of the bed and threw it over her thick, bright hair.

‘You are going to check on your wretched horse, I suppose.’ Mathilde’s voice was little more than a throaty growl. ‘I do not see why. God knows all of those creatures are tended with as much care as if they were children. It is mean of you to leave me here all alone.’

Emma, who loved the outdoors, who loved horses, dogs, and hunting, and who was happiest when she was riding along the Norman shore beneath high chalk cliffs, knew better than to try to explain her errand to Mathilde, who detested all of those things. Emma was sorry that Mathilde was ill and bored, but she would go mad if she could not breathe some fresh air and be alone for just a little while. The two of them had been pent up together within doors for three full days.

She lifted a heavy, fur-lined black cloak from its peg on the wall and threw it over her shoulders.

‘I will not be gone long,’ she said.

Mathilde, though, had thought of another objection.

‘What if the shipmen return while you are down there?’ she demanded. ‘You cannot trust those Danish brutes not to molest you if they come upon you alone and unprotected.’

Emma fastened her cloak beneath her chin, pondering this warning.

The Danish king, Swein Forkbeard, had petitioned her brother for winter harbour along Normandy’s northern coast, and Duke Richard, unwilling to offend the fierce warrior king, had granted it. To Richard’s fury, though, Forkbeard’s own ship and a dozen more had sailed into Fécamp’s harbour two days ago, forcing her brother out of courtesy to invite the king to join his family at the palace.

The king had accepted swiftly and had settled into her brother’s great hall with a score of his companions – rough, hard-faced warriors with only the thinnest gloss of civilization about them in spite of the wealth of gold that they flaunted on their wrists and arms. Mathilde, sick with the ague, had kept to her bed. Richard’s wife, Judith, only a few weeks out of childbed, had done the same. So it was Emma’s mother, Dowager Duchess Gunnora, with only her youngest daughter at her side, who had offered the king the welcome cup upon his arrival in the hall. The duchess, proud of her Danish heritage and her blood ties to the Danish throne, nevertheless had no illusions about Swein Forkbeard. She presented Emma to him with formal courtesy, then banished her daughter to the private quarters with all of the other young women.

Emma had not been sorry to go. Forkbeard had greeted her with cold, fiercely calculating eyes and a silent nod. His brooding gaze seemed to weigh her, as if she were not a woman but a commodity that could be bought and sold – a trinket that he might purchase in the market at Rouen. She had coloured beneath his fixed, brutal stare, and had wanted to take to her heels to escape it. But she had forced herself to walk slowly from the hall, chin held high, acutely aware of the shipmen all around her who raked her with merciless eyes.

These were men who made their living by murder and rape, men who had been baptized to Christ but whose souls still belonged to heathen gods, or so she had heard. Their grim, weather-scarred faces had haunted her dreams that night, and like her brothers, she wished that Forkbeard and his shipmen had never come to Fécamp. Today, though, the palace was emptied of Danes.

‘The shipmen have gone to the harbour to inspect their vessels for storm damage. They will likely not return until dark. I will be back long before that, and I promise I will keep you company then until we put out the candles.’ With that she slipped from the room before Mathilde could think of any other objections.

The courtyard was deserted as she made her way towards the stables, and the air was so frigid that it hurt to breathe. She followed the wall, grasping at its stones with one hand as she navigated the slippery mud and slush that had been churned up by men and horses. Emma’s snow-white mare, Ange, whickered a greeting, and Emma nuzzled the horse’s neck, warming her face against its thick winter coat. A moment later, though, she heard a commotion in the stable yard that worried her.

Could the men have returned so soon? Surely not all of them. They would have made a great deal more clamour.

Using Ange as a screen, Emma peered towards the wide doorway and saw Richard and Swein Forkbeard leading their mounts towards the stable. She had always thought her brother quite tall, but the Danish king bested him by half a head. They were the same age – both of them very old by her reckoning, for Richard had been born more than twenty years before Emma. But the king of the Danes, with his white hair and long white beard, worn forked and braided, looked far older. There was a sternness about Swein Forkbeard’s countenance, a hard-eyed ruthlessness that frightened her. He even frightened Richard, she was certain, although he masked it with courtesy.

She had no wish to greet the Danish king again, or to face her brother’s wrath at finding her here, so she shied behind her horse to wait for them to go away. They seemed in no hurry, in spite of the cold. Richard, in halting Danish, was relating the pedigree of the king’s mount and doing his best to explain what he looked for in breeding his horse stock.

She smiled at her brother’s clumsy efforts with Swein’s tongue. Like all of the Duchess Gunnora’s children, he had learned Danish at his mother’s knee. And like most of his siblings, he had abandoned it at an early age. Emma had been the only one to embrace it, and she could speak as fluently in Danish as she could in Frankish or Breton or Latin. She had even learned some of the English used by prelates who sometimes visited her brother from across the Narrow Sea.

Neither Richard nor her brother Robert, the archbishop, knew of Emma’s gift of tongues, as her mother called it. Gunnora had advised Emma to keep this remarkable skill a secret. Use it to listen, she had said, rather than to speak. You will be surprised at what you will learn.

Emma listened now and realized, with a start, that the conversation between her brother and the Danish king had moved from the breeding of horses to the breeding of children.

‘A marriage alliance would be in both our interests,’ Swein Forkbeard said. ‘I have two sons who need wives. One of your sisters might do, and you would gain much from such a marriage, I promise you. Of course, were you to reject it, you could lose a great deal.’ There was silence for a moment, and then the king said, his voice speculative, taunting, ‘How much, I wonder, are you prepared to lose?’

Emma covered her mouth with her hand, shocked by the clear threat in Forkbeard’s words. What would he do? Send shipmen to ravage Normandy unless Richard sent one of his sisters to Denmark to wed one of Forkbeard’s sons?

She held her breath, waiting for Richard’s reply.

‘My sisters are overly young to wed.’ Her brother’s fumbled words were so casual that Emma wondered if he had understood all that the Danish king had said.

‘Age matters little,’ Forkbeard replied, his tone amiable now. ‘My youngest son has seen only ten winters, but like his elder brother, he is already a skilled shipman and warrior. As for your sisters,’ he paused, and Emma twisted her fingers nervously in Ange’s mane as she waited for him to go on, ‘you must not be too tender in your care of them. The Lady Emma seems ripe for bedding. You would do well to breed her now, for a good price, or you might find that you have left it too late.’

Emma felt the blood rise to her face, humiliation and anger warring with shock and fear. Surely Richard would not agree to sell her to Denmark! It was a harsh, brutal place, barely Christian. Her family could trace their bloodline back to the northern lands, but that was in the past. Surely it was not part of their future. Denmark was a land of fierce men ruled by a ruthless king. Swein Forkbeard had not inherited his crown but had won it in a battle to the death waged against his own father. Richard could not allow her to marry into a family such as that!

Her blood pounded in her ears, and she had to strain to hear her brother’s response to Forkbeard’s words.

‘Your proposal does my family great honour,’ Richard said. ‘You will understand, of course,’ he went on, his voice smoothly persuasive in spite of his broken Danish, ‘that a betrothal is too delicate a matter to be settled quickly. There are many things to consider and to weigh, and as you know, I have two sisters. You have yet to meet the elder, who, by tradition, should naturally be the first to wed.’

She did not hear the Danish king’s reply, for the men’s voices faded, replaced by the clink of bridles as grooms led the horses to their stalls. Emma remained rooted to the spot where she stood, her face buried in Ange’s neck, her thoughts in turmoil over what she had heard.

Swein Forkbeard’s proposal must carry great weight with her brother. Richard was a realist. He would consider the sacrifice of a younger sister a small price to pay for Norman peace with Denmark. It would be terrible for the bride, though – banished to a hostile, distant land. Mathilde would hate it, even as Emma would. She felt her throat constrict at the very thought of it.

No, her brother could not do such a thing to either of his sisters. He would not send them so far away. He had wed their elder sisters to great lords in Brittany and Frankia, securing his borders and adding considerably to his treasure. Surely he would use Mathilde and herself in a similar manner, for Normandy’s border was long and Richard had need of allies.

But Richard was ambitious. A royal marriage, even to a son of the barbarous Swein Forkbeard, would enhance her brother’s prestige throughout Europe. Forkbeard may be a Viking warlord rather than a godly Christian king, but all of Europe feared him, and that made him a valuable ally. She could easily imagine Richard succumbing to that argument, and she feared what he might be plotting with the Danish king in his private chamber.

She whispered a few endearments into Ange’s ear, then, afraid that Forkbeard’s men might arrive hard upon his heels, she hurried back towards the palace. She would say nothing of what she had heard to Mathilde. Their mother, surely, would have some say in the matter, yet Emma was frightened for her elder sister.

A slender needle of anxiety began to prick her insides. She did not trust Richard.

25th December 1001

Rochester, Kent

In England that December the fierce snowstorm blinded and buried countless travellers caught on the high chalk downs of Wessex, even within a few short steps of shelter. Near Durham in Northumbria the snow piled so high on the thatched roof of Lord Thorkeld’s great hall that it collapsed of its own weight, burying the lord and his family and retainers, twenty folk in all. On the Isle of Wight a storm surge swept an entire village into the sea. In Devon the once prosperous towns of Pin-hoo and Clyst, their houses, workshops, and storerooms razed to the ground during the previous summer’s Danish raids, were buried beneath fifteen feet of snow, as if they had never existed.

In the king’s hall at Rochester, Æthelred II of England and his councillors sat at table for the winter feast swathed in furs against the bitter cold. Their mood would have been dour even had the weather been more moderate. They drank their Christmas ale with grim determination rather than pleasure, their company unleavened by the presence of any women. The king’s mother, a force at court for nearly twenty-five years, had gone to God some five weeks before, in November, on the Feast of St Hilda. The king’s lady wife, brought to childbed on Christmas Eve for the eleventh and final time, had breathed her last on Christmas morning. Her cold body lay beneath the vaulted wooden ceiling of the king’s chapel, mourned by her attendants. The child, born too soon and perhaps sensing his loss, found no comfort in the arms of his wet nurse. Whenever the roaring of the wind and the desultory muttering of men momentarily abated, his feeble cry wafted through the hall like the wail of a soul wandering between heaven and earth. The women tending the babe shook their heads, lips pursed. The child was not long for this world, they deemed, for he would not suck.