скачать книгу бесплатно

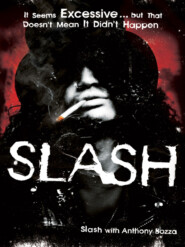

Slash: The Autobiography

Anthony Bozza

Slash Slash

It seems excessive…but that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen.The mass of black curls. The top hat. The cigarette dangling from pouty lips. These are the trademarks of one of the world’s greatest and most revered guitarists, a celebrity musician known by one name: Slash.Saul “Slash” Hudson was born in Hampstead to a Jewish father and a black American mother who created David Bowie’s look in The Man Who Fell to Earth. He was raised in Stoke until he was 11, when he and his mother moved to LA. Frequent visitors to the house were David Bowie, Joni Mitchell, Ronnie Wood and Iggy Pop.At this time Slash got into BMX bikes and would eventually turn professional, winning major awards and money, but at 15 his grandmother gave him his first guitar. Sessions with numerous local LA rock bands followed until a fateful meeting with singer W Axl Rose…and the rest was rock history. Guns N’ Roses spent two years builiding their reputation before Appetite for Destruction was unleashed on an unsuspecting world.Chart success and global domination followed but with it came the inevitable fall – addicted to heroin, booze and cigarettes the band imploded in a rift between Axl and Slash that is as deep today as ever. But with a new wife, kids and new band Velvet Revolver, Slash is back on track. As raucous and edgy as his music, Slash sets the record straight and tells the real story as only Slash can.

Slash

Slash with Anthony Bozza

Copyright

HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright © 2007 by Dik Hayd International, LLC.

Slash and Anthony Bozza assert the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007257751

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2007 ISBN: 9780007481033

Version: 2018-08-23

To my loving family, for all their support through the good times and the bad

And to Guns N’ Roses fans everywhere, old and new; with out their undying loyalty and limitless patience, none of this would matter

Contents (#uf6afb24e-da28-5b21-9b59-49c5f9013fc6)

Copyright

Introduction

1. Stoked

2. Twenty-Inch-High Hooligans

3. How to Play Rock-and-Roll Guitar

4. Education High

5. Least Likely to Succeed

6. You Learn to Live Like an Animal

7. Appetite for Dysfunction

8. Off to the Races

Photographic Insert

9. Don’t Try This at Home

10. Humpty Dumpty

11. Choose Your Illusion

12. Breakdown

13. Coming Up for Air

If Memory Serves

Photography Credits

About the Authors

Credits

About the Publisher

Having Considered All Things

It felt like a baseball bat to my chest, but one swung from the inside. Clear blue spots lit up the corners of my vision. It was abrupt, bloodless, silent violence. Nothing was visibly broken, nothing had changed to the naked eye, but the pain made my world stand still. I kept playing; I finished the song. The audience didn’t know that my heart had done a somersault just before the solo. My body had delivered its karmic retribution; reminding me, onstage, of how many times I’d intentionally served it up a similar loop-de-loop.

The jolt quickly became a dull ache that almost felt good. In any case, I felt more alive than I had a moment before, because I was more alive. The machine in my heart had reminded me of just how precious this life is. Its timing was impeccable: with a full house in front of me, while I played my guitar, I got the message loud and clear. I got it a few times that night. And I got it every time I was onstage for the rest of that tour, though I never knew when it was coming.

A doctor installed an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in my heart when I was thirty-five. It’s a three-inch-long battery-powered generator that was inserted through an incision in my armpit. It constantly monitors my heart rate, delivering electroshocks whenever my heart beats too dangerously fast or slow. Fifteen years of overdrinking and drug abuse had swollen that organ to one beat short of exploding. When I was finally hospitalized, I was told I had six weeks to live. It’s been six years since then and this piece of machinery has saved my life more than a few times. I’ve enjoyed a convenient side effect that the doctor did not intend: when my indulgences have caused my heart to beat too dangerously slow, my defibrillator has popped off, keeping death from my door for one more day. It also shocks my heart into submission when it beats fast enough to court cardiac arrest.

It’s a good thing I got it adjusted before the first Velvet Revolver tour. I did that one sober for the most part; sober enough that the excitement of playing with a band I believed in to fans who believed in us moved me to my core. I hadn’t been that inspired in years. I ran all over the stage; I basked in our collective energy. My heart raced with excitement hard enough to trigger the machine inside me onstage every night. It wasn’t pleasant but I began to welcome those reminders. I saw them for what they were. Strange moments of alienated clarity, moments out of time that encapsulated a life’s worth of hard-won wisdom.

1

Stoked

I was born on July 23, 1965, in Stoke-on-Trent, England, the town where Lemmy Kilmister of Motörhead was born twenty years before me. It was the year rock and roll as we know it became greater than the sum of its parts; the year a few isolated bands changed pop music forever. The Beatles released Rubber Soul that year and the Stones released Rolling Stones No. 2, the best of their collections of blues covers. There was a creative revolution afoot that has never been equaled and I’m proud to be a by-product of it.

My mom is an African American and my dad is English and white. They met in Paris in the sixties, fell in love, and had me. Their brand of interracial intercontinental communion wasn’t the norm; and neither was their boundless creativity. I thank them for being who they are. They exposed me to environments so rich and colorful and unique that what I experienced even while very young made a permanent impression on me. My parents treated me as an equal as soon as I could stand. And they taught me, on the fly, how to deal with whatever came my way in the only type of life I’ve ever known.

Tony Hudson and his sons, 1972. Slash looks exactly like his son London here.

My mom, Ola, was seventeen and my dad, Anthony (“Tony”), was twenty when they met. He was born a painter, and like painters historically do, he left his stuffy hometown to find himself in Paris. My mom was precocious and exuberant, young and beautiful; she’d left Los Angeles to see the world and make connections in fashion. When their journeys intersected they fell in love, then got married in England. And then I came along and they set about creating their life together.

My mom’s career as a costume designer started around 1966, and over the course of it, her clients included Flip Wilson, Ringo Starr, and John Lennon. She also worked for the Pointer Sisters, Helen Reddy, Linda Ronstadt, and James Taylor. Sylvester was one of her clients, too. He is no longer with us, but he was once a disco artist who was like the gay Sly Stone. He had a great voice and he was a supergood person in my eyes; he gave me a black-and-white rat that I named Mickey. Mickey was a badass. He never flinched when I fed rats to my snakes. He survived a fall from my bedroom window after he was tossed out by my younger brother, and was no worse for the wear when he showed up at our back door three days later. Mickey also survived the accidental removal of a section of his tail when the inner chassis of our sofa bed cut it off, as well as close to a year without food or water. We left him behind by mistake in an apartment that we used as storage space, and when we eventually popped in to pick up some boxes, Mickey came up to me congenially as if I’d been gone only a day, as if to say, “Hey! Where you been?”

Mickey was one of my more memorable pets. There have been many, from my mountain lion, Curtis, to the hundreds of snakes I’ve raised. Basically I am a self-taught zookeeper and I definitely relate to the animals I’ve lived with better than to most of the humans I’ve known. Those animals and I share a point of view that most people forget: at the end of the day life is about survival. Once that lesson is learned, earning the trust of an animal that might eat you in the wild is a defining and rewarding experience.

SOON AFTER I WAS BORN, MY MOTHER returned to L.A. to expand her business and to lay the financial foundation our family was built upon. My dad raised me in England at his parents’, Charles and Sybil Hudson’s, home for four years—and it wasn’t easy on him. I was a pretty intuitive kid, but I could not discern the depth of the tension there. My dad and his dad, Charles, from what I understand, had less than the best relationship. Tony was the middle of three sons, and he was every bit the middle child upstart. His younger brother, Ian, and his older brother, David, were much more in step with the family’s values. My dad went to art school; he was everything his father wasn’t. Tony was the sixties; and he stood up for his beliefs as wholeheartedly as his father condemned them. My grandfather Charles was a fireman from Stoke, a community that had somehow skated through history unchanged. Most residents of Stoke never leave; many, like my grandparents, had never ventured the hundred or so miles south to London. Tony’s unyielding vision of attending art school and making a living through painting was something Charles could not stomach. Their clash of opinion fueled constant arguments and often led to violent exchanges; Tony claims that Charles beat him senseless on a regular basis for most of his youth.

My grandfather was as consummately representative of 1950s Britain as his son was of the sixties. Charles wanted to see everything in its right place while Tony wanted to rearrange and repaint it all. I imagine that my grandfather was properly appalled when his son returned from Paris in love with a carefree black American. I wonder what he said when Tony told him that he intended to be married and raise their newborn child under their roof until he and my mom got their affairs in order. All things considered, I’m touched by how much diplomacy was displayed by the parties involved.

MY DAD TOOK ME TO LONDON AS SOON as I could handle the train ride. I was maybe two or three, but instinctively I knew how far away it was from Stoke’s unending miles of brown brick row houses and quaint families because my dad was into a bit of a bohemian scene. We’d crash on couches and not come back for days. There were Lava lamps and black lights, and the electric excitement of the open booths and artists along Portobello Road. My dad never considered himself a Beat, but he had absorbed that kind of lifestyle through osmosis. It was as if he had handpicked the highlights of that type of life: a love of adventure, hitting the road with nothing but the clothes on your back, finding shelter in apartments full of interesting people. My parents taught me a lot, but I learned their greatest lesson early—nothing else is quite like life on the road.

I remember the good things about England. I was the center of my grandparents’ attention. I went to school. I was in plays: The Twelve Days of Christmas; I was the lead in The Little Drummer Boy. I drew all the time. And once a week I watched The Avengers and The Thunderbirds. Television in late sixties England was extremely limited and reflected the post–World War II, Churchill view of the world of my grandparents’ generation. There were only three channels back then, and aside from the two hours a week that any of them played those two programs, all three played only the news. It’s no wonder that my parents’ generation threw themselves headfirst into the cultural shift that was afoot.

Once Tony and I joined Ola in Los Angeles, he never spoke to his parents again. They disappeared from my life quickly and I often missed them growing up. My mother encouraged my father to stay in touch but it made no difference; he had no interest. I didn’t see my English relatives again until Guns N’ Roses became well known. When we played Wembley Stadium in 1992, the Hudson clan came out in force: backstage before the show I witnessed one of my uncles, my cousin, and my grandfather, on his very first trip to London from Stoke, down every drop of liquor in our dressing room. Consumed in full, our booze rider in those days would have killed anyone but us.

MY FIRST MEMORY OF LOS ANGELES IS the Doors’ “Light My Fire” blasting from my parents’ turntable, every day, all day long. In the late sixties and early seventies L.A. was the place to be, especially for young Brits involved in the arts or music: there was ample creative work compared to the still-stodgy system in England and the weather was nothing but paradise compared to London’s rain and fog. Besides, deserting England for Yankee shores was the best way to flip off the system and your upbringing—and my dad was more than happy to do so.

My mother continued her work as a fashion designer while my father parlayed his natural artistic talent into graphic design. My mom had connections in the music industry so her husband was soon designing album covers. We lived off Laurel Canyon Boulevard in a very sixties community up at the top of Lookout Mountain Road. That area of Los Angeles has always been a creative haven because of the bohemian nature of the landscape. The houses are set right into the mountainside among lush foliage. They are bungalows with guesthouses and any odd number of structures that allow for very organic, communal living. There was a very cozy enclave of artists and musicians living up there when I was young: Joni Mitchell lived a few houses down from us. Jim Morrison lived behind the Canyon Store at that time, as did a young Glen Frey, who was just putting together the Eagles. It was the kind of atmosphere where everyone was connected: my mom designed Joni’s clothes while my dad designed her album covers. David Geffen was a close friend of ours, too, and I remember him well. He signed Guns N’ Roses years later, though when he did he didn’t know who I was—and I didn’t tell him. He called Ola at Christmas in 1987 and asked her how I was doing. “You should know how he’s doing,” she said, “you just put his band’s record out.”

AFTER A YEAR OR TWO IN LAUREL CANYON we moved south to an apartment on Doheny. I changed schools, and that is when I discovered just how differently the average kid lived. I never had a traditional “kid” room full of toys and primary colors. Our homes were never painted in common neutral tones. The essence of pot and incense usually hung in the air. The vibe was always bright, but the color scheme was always dark. It was fine with me, because I was never concerned with connecting with kids my age. I preferred the company of adults because my parents’ friends are still some of the most colorful characters I’ve ever known.

I listened to the radio 24/7, usually KHJ on the AM dial. I slept with it on. I did my schoolwork and got good grades, although my teacher said I had a short attention span and daydreamed all the time. The truth is, my passion was art. I loved the French Postimpressionist painter Henri Rousseau and, like him, I drew jungle scenes full of my favorite animals. My obsession with snakes started very early. The first time my mother took me to Big Sur, California, to visit a friend and camp up there, I was six years old and I spent hours in the woods catching snakes. I’d dig under every bush and tree until I’d filled an unused aquarium. Then I’d let them go.

That wasn’t the only excitement I experienced on that outing: my mom and her friend were similarly wild, carefree young women, who enjoyed racing my mom’s Volkswagen Bug along the twisting cliffside roads. I remember speeding along in the passenger seat scared stiff, looking out my window at the rocks and ocean that lay below, just inches past my door.

Slash used to be convinced that he was a dinosaur; then he entered his Mowgli phase.

The sight of a guitar still turns me on.

MY PARENTS’ RECORD COLLECTION WAS flawless. They listened to everything from Beethoven to Led Zeppelin and I continued to find undiscovered gems in their library well into my teens. I knew every artist of the day because my parents took me to concerts constantly, and since my mom took me to work with her often as well. At a very early age I was exposed to the inner workings of entertainment: I saw the inside of many recording studios and rehearsal spaces, as well as TV and film sets. I saw many of Joni Mitchell’s recording and rehearsal sessions; I also saw Flip Wilson (a comic who was huge then but whom time has forgotten) record his TV show. I saw Australian pop singer Helen Reddy rehearse and perform, and was there when Linda Ronstadt played the Troubador. Mom also took me along when she outfitted Bill Cosby for his stand-up gigs and made his wife a few one-off pieces; I remember going with her to see the Pointer Sisters. All of that was over the course of her career, but when we lived at that apartment on Doheny, her business was really taking off: Carly Simon came over to the house, soul singer Minne Ripperton as well. I met Stevie Wonder and Diana Ross. My mom tells me that I met John Lennon, too, but unfortunately I don’t remember that at all. I do remember meeting Ringo Starr: my mom designed the very Parliament-Funkadelic outfit that Ringo wore on the cover of his 1974 album, Goodnight Vienna. It was high-waisted and metallic gray with a white star in the middle of the chest.

Every backstage or soundstage scene that I saw with my mother worked some kind of strange magic on me. I had no idea what was going on, but I was fascinated by the machinations of performance back then and I still am now. A stage full of instruments awaiting a band is exciting to me. The sight of a guitar still turns me on. There is an unstated wonder in both of them: they hold the ability to transcend reality given the right set of players.

Slash and his brother, Albionn, at the La Brea Tar Pits.

MY BROTHER, ALBION, WAS BORN IN December 1972. That changed the dynamic of my family a bit; suddenly there was a new personality among us. It was cool to have a little brother, and I was glad to be one of his caretakers: I loved it when my parents would ask me to look after him.

But it wasn’t too long after that that I began to notice a greater change in our family. My parents weren’t the same when they were together and too often they were apart. Things started to get bad I think once we moved into the apartment on Doheny Drive and my mom’s business began to really succeed. Our address was 710 North Doheny, by the way, which is now a vacant lot where Christmas trees are sold in December. I should also mention that our next-door neighbor in that building was the original, self-proclaimed Black Elvis, who can be booked for parties in Las Vegas—if anyone’s interested.

Now that I’m older I can see some of the obvious issues that ate away at my parents’ relationship. My father never liked how close my mother was to her mother. It bruised his pride when his mother-in-law helped us financially, and he was never fond of her involvement in the family. His drinking didn’t help things: my dad used to like to drink—a lot. He was a stereotypically bad drinker: he was never violent, because my dad is much too smart and complicated to ever express himself through brute violence, but he had a bad temper under the influence. When he was drunk, he’d act out by making inappropriate comments at the expense of those in his presence. Needless to say, he burned many bridges that way.

I was only eight, but I should have known that something was really wrong. My parents never treated each other with anything but respect, but in the months before they split up, they completely avoided each other. My mom was out most nights and my dad spent those nights in the kitchen, somber and alone, drinking red wine and listening to the piano compositions of Erik Satie. When my mom was home, my dad and I went out on long walks.

He walked everywhere, in England and Los Angeles. In pre–Charles Manson L.A.—before the Manson clan murdered Sharon Tate and her friends—we also used to hitchhike everywhere. L.A. was innocent before that; those murders signified the end of the utopian ideals of the sixties Flower Power era.

My childhood memories of Tony are cinematic; all of them afternoons spent looking up at him, walking by his side. It was on one of those walks that we ended up at Fatburger, where he told me that he and Mom were separating. I was devastated; the only stability I’d known was done. I didn’t ask questions, I just stared at my hamburger. When my mom sat me down to explain the situation later that night, she pointed out the practical benefits: I’d have two houses to live in. I thought about that for a while, and it made sense in a way but it sounded like a lie; I nodded while she spoke but I stopped listening.

My parents’ separation was amicable yet awkward because they didn’t divorce until years later. They often lived within walking distance of each other and socialized in the same circle of friends. When they split up, my little brother was just two years old, so for obvious reasons they agreed that he should be in his mother’s care, but left me the option of living with either one of them so I chose to live with my mother. Ola supported us as best as she could, traveling constantly to wherever her work took her. Out of necessity, my brother and I were shuffled between my mom’s house and my grandmother’s home. My parents’ house had always been busy, interesting, and unconventional—but it had always been stable. Once their bond was broken, though, constant transition became the norm for me.

The separation was very hard on my father and I didn’t see him for quite a while. It was hard on all of us; it finally became reality to me once I saw my mother in the company of another man. That man was David Bowie.

IN 1975, MY MOTHER STARTED WORKING closely with David Bowie while he was recording Station to Station; she had been designing clothes for him since Young Americans. So when he signed on to star in the film The Man Who Fell to Earth my mom was hired to do the costumes for the film, which shot in New Mexico. Along the way, she and Bowie embarked on a semi-intense affair. Looking back on it now, it might not have been that big of a deal, but at the time, it was like watching an alien land in your backyard.

After my parents split up, my mom, my brother, and I moved into a house on Rangely Drive. It was a very cool house: the walls of the living room were sky blue and emblazoned with clouds. There was a piano, and my mom’s record collection took up an entire wall. It was inviting and cozy. Bowie came by often, with his wife, Angie, and their son, Zowie, in tow. The seventies were unique: it seemed entirely natural for Bowie to bring his wife and son to the home of his lover so that we might all hang out. At the time my mother practiced the same form of transcendental meditation that David did. They chanted before the shrine she maintained in the bedroom.

I accepted David once I got to know him because he’s smart, funny, and intensely creative. My experience of him offstage enriched my experience of him onstage. I went to see him with my mom at the L.A. Forum in 1975, and, as I have been so many times since, the moment he came out onstage, in character, I was captivated. His entire concert was the essence of performance. I saw the familiar elements of a man I’d gotten to know exaggerated to the extreme. He had reduced rock stardom to its roots: being a rock star is the intersection of who you are and who you want to be.

2

Twenty-Inch-High Hooligans

No one expects the rug to be yanked out from under them; life-changing events usually don’t announce themselves. While instinct and intuition can help provide some warning signs, they can do little to prepare you for the feeling of rootlessness that follows when fate flips your world upside down. Anger, confusion, sadness, and frustration are shaken up together inside you like a snow globe. It takes years for the emotional dust to settle as you do your best just to see through the storm.

My parents’ separation was the picture of an agreeable split. There were no fights or ugly behavior, no lawyers and no courts. Yet it still took me years to come to terms with the hurt. I lost a piece of who I was and had to redefine myself on my own terms. I learned a lot, but those lessons didn’t help me later on when the only other family I’d known disintegrated. I saw the signs that time, when Guns N’ Roses started to come apart at the seams. But even though I did the leaving that time, the same blizzard of feelings lay in wait for me, it was every bit as hard to find my way back to my path again.

When my parents got separated, I was transformed by the sudden change. Inside I was still a good kid, but on the outside I became a problem child. Expressing my emotions is still one of my weaknesses, and what I felt then defied words, so I followed my natural inclinations—I acted out drastically and became a bit of a disciplinary problem at school.

At home, my parents’ promise of a two-abode existence that wouldn’t change a thing hadn’t come to pass. I hardly saw my dad for the first year or so that they were apart, and when I did, it was intense and weird. As I mentioned, the divorce hit him hard and watching him adjust was difficult for me; for a while he couldn’t work at all. He lived meagerly and hung out among his artist friends. When I visited with him, I was along for the ride as he and his friends hung out, drank a lot of red wine, and discussed art and literature, the conversation typically turning to Picasso, my dad’s favorite artist. Dad and I would go on adventures, too, either to the library or the art museum, where we’d sit together and draw.

My mother was home less than ever; she worked constantly, traveling often to support my brother and me. We spent a lot of time with my grandmother Ola Sr., who was always our saving grace when Mom couldn’t make ends meet. We also spent time with my aunt and cousins who lived in greater South Central L.A. Their house was boisterous, filled with the energy of a lot of kids. Our visits there brought some regularity to our idea of family. But all things considered, I had a lot of time on my hands and I took advantage of it.

Once I was twelve, I grew up fast. I had sex, I drank, I smoked cigarettes, I did drugs, I stole, I got kicked out of school, and on a few occasions I would have gone to jail if I hadn’t been underage. I was acting out, making my life as intense and unstable as I felt inside. A trait that has always defined me really came into its own in this period: the intensity with which I pursue my interests. My primary passion, by the time I was twelve, had shifted from drawing to bicycle motocross.

In 1977, BMX racing was the newest extreme sport to follow the surfing and skateboarding craze of the late sixties. It already had a few bona fide stars, such as Stu Thompson and Scott Breithaupt; a few magazines, such as Bicycle Motocross Action and American Freestyler, and more semi-pro and pro competitions were popping up constantly. My grandmother bought me a Webco and I was hooked. I started winning races and was listed in a couple of the magazines as an up-and-coming rider in the thirteen to fourteen age category. I loved it; I was ready to go pro once I’d landed a sponsor, but something was missing. My feelings weren’t clear enough to me to vocalize just what BMX didn’t satisfy inside me. I’d know it when I found it a few years later.

After school, I hung out at bike shops and became part of a team riding for a store called Spokes and Stuff, where I began to collect a bunch of much older friends—some of the other older guys worked at Schwinn in Santa Monica. Ten or so of us would ride around Hollywood every night and all of us but two—they were brothers—came from disturbed or broken domestic situations of some kind. We found solace in one another’s company: our time spent together was the only regular companionship any of us could count on.

We would meet up every afternoon in Hollywood and ride everywhere from Culver City to the La Brea Tar Pits, treating the streets as our bike park. We’d jump off every sloped surface we could find, and whether it was midnight or the middle of rush hour, we always disrespected the pedestrians’ right of way. We were just scrappy kids on twenty-inch-high bikes, but multiplied by ten, in a pack, whizzing down the sidewalk at top speed, we were a force to be reckoned with. We’d jump onto a bus bench, sometimes while some poor stranger was sitting there, we’d hop fire hydrants, and we’d compete constantly to outdo one another. We were disillusioned teenagers trying to navigate difficult times in our lives, and we did so by bunny-hopping all over the sidewalks of L.A.

We’d ride this dirt track out in the Valley, by the youth center in Reseda. It was about fifteen miles away from Hollywood, which is an ambitious goal on a BMX bike. We used to hitch rides on bumpers over Laurel Canyon Boulevard to cut down on our travel time. It’s nothing I’d advise, but we treated passing cars like seats on a ski chairlift: we’d wait on the shoulder, then one by one we’d grab a car and ride it up the hill. Balancing a bike, even one with a low center of gravity, while holding on to a car driving thirty or forty miles an hour is thrilling but tricky on flat ground; attempting it on a series of tight uphill S curves like Laurel Canyon is something else. I’m still not sure how none of us were ever run over. It surprises me more to remember that I did that ride, both up and down hill, without brakes more often than not. In my mind, being the youngest meant that I had something to prove to my friends every time we rode: judging by the looks on their faces after some of my stunts, I succeeded. They might have been only teenagers but my friends weren’t easily impressed.

To tell you the truth, we were a gnarly little gang. One of them was Danny McCracken. He was sixteen; a strong, heavy, silent type, he was already a guy everyone instinctively knew not to fuck with. One night Danny and I stole a bike with bent forks and while he deliberately bunny-hopped it to break the forks and make us all laugh, he fell over the handle-bars and slashed his wrist wide open. I saw it coming and watched it as if in slow-motion as blood started squirting everywhere.

“Ahhh!” Danny shouted. Even in pain, Danny’s voice was oddly soft-spoken considering his size—kind of like Mike Tyson’s.

“Holy shit!”

“Fuck!”

“Danny’s fucked up!”

Danny lived just around the corner, so two of us held our hands over his wrist as blood kept squirting out between our fingers as we walked him home.

We got to his porch and rang the bell. His mom came to the door and we showed her Danny’s wrist. She looked at us unfazed, in disbelief.

“What the fuck do you want me to do about it?” she said, and slammed the door.

We didn’t know what to do; by this time Danny’s face was pale. We didn’t even know where the nearest hospital was. We walked him back down the street, blood still spurting all over us, and flagged down the first car we saw.