Полная версия:

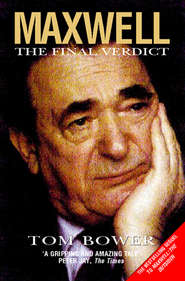

Maxwell: The Final Verdict

Tom Bower

MAXWELL

THE FINAL VERDICT

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1996

Copyright © Tom Bower 1995

Tom Bower asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007292875

Ebook Edition © JUNE 2012 ISBN 9780007394999

Version: 2016-11-09

Dedication

To Sophie

Epigraph

You are my teacher and all my life you have tried to demonstrate the principles underlying every action or inaction … Above all, you have given me the sense of excitement of having dozens of balls in the air and the thrill of seeing some of them land right.

KEVIN MAXWELL, written to his father in 1988

The Maxwell Foundation will be one of the richest of its kind in the world.

JOE HAINES, 1988

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Preface

1 The Autopsy – 9 November 1991

2 The Secret – 5 November 1990

3 Hunting for Cash – 19 November 1990

4 Misery – December 1990

5 Fantasies – January 1991

6 Vanity – March 1991

7 Flotation – April 1991

8 A Suicide Pill – May 1991

9 Two Honeymoons – June 1991

10 Buying Silence – July 1991

11 Showdown – August 1991

12 ‘Borrowing from Peter to Pay Paul’ – September 1991

13 Whirlwind – October 1991

14 Death – 2 November 1991

15 Deception – 6 November 1991

16 Meltdown – 21 November 1991

17 The Trial – 30 May 1995

Epilogue

Keep Reading

Notes

Company Plan

Dramatis Personae

Glossary of Abbreviations

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Preface

On 12 May 1989, Peter Jay signed a short letter marked ‘Private and Confidential’ addressed to George Potter OBE, a director of Control Risks, one of Britain’s leading private detective agencies. Jay, the chief of staff to Robert Maxwell, thanked Potter, a former police officer, for ‘your letter and for the time you gave to meeting me and preparing it’.

Potter’s letter had described his surveillance of ‘the location and the levels of background radiation in the area’. Potter was referring in cryptic fashion to a surreptitious reconnaissance mission which he had undertaken around my home in Hampstead, north-west London. He continued: ‘Extremely sophisticated equipment does exist which might overcome the technical problems. Its acquisition would cost an estimated £50,000.’ The private detective was describing a scanner which would emit rays capable of penetrating my home and ‘reading’ the contents of my computer’s hard disc.

Wisely, Potter cautioned Jay about the problems. First, the detective wanted to be paid in advance the £50,000 for the equipment and also some fees. Secondly, Potter warned, he had ‘reservations as to the possibility of obtaining the evidence you require and the ability to keep the operation covert’. The detective’s concerns were understandable. A van carrying the scanner would be parked at the bottom of my garden in a narrow service road used by the Hampstead postal sorting office. Remaining unobtrusive for long periods would be difficult.

Jay, who had once basked in the glorious description as one of Britain’s ‘cleverest men’, was not slow to grasp Potter’s cautionary tone but was sensitive to the dissatisfaction that this report would cause his demanding employer. Little had been achieved since, one month earlier, he had received a briefing from Tony Frost, an assistant editor of the Daily Mirror, following his investigation around my Hampstead home.

Frost had accurately noted my address and identified my car, before reporting that ‘neighbours say his working hours are “rather erratic” with frequent trips away’ and that I ‘spent “a full working week” at the offices or studios of the various TV companies who commission his work’. Curiously, he noted that my newsagent ‘seemed to know Bower quite well’. After alluding to my financial status, Frost observed that my road is ‘typical of the more up-market parts of Hampstead’ and flatteringly noted, ‘the house looked to be tastefully and expensively decorated inside’.

Copies of Frost’s memorandum were also sent to Eve Pollard (then editor of the Sunday Mirror), Ernest Burrington, (then editor of the People) and Joe Haines (then a Daily Mirror columnist and a director of the Mirror Group) – all owned by Maxwell’s Mirror Group Newspapers.

Jay filed Frost’s report in his bulging ‘Bower File’, which was marked in large letters ‘Private and Confidential’, reflecting the heading of every document it contained. Each letter on the topic signed by the chief of staff urged its recipient to treat the matter with utmost secrecy. Jay had become rather proficient in conducting the operation.

Ever since his employer had heard in summer 1987 that I was planning to write Maxwell: the Outsider, an unauthorised biography of himself, Peter Jay had been employed as his chief of intelligence to gather and co-ordinate information about my activities and identify those people whom I was interviewing. On one occasion, detectives had clearly followed me to a meeting with Anne Dove, Maxwell’s former secretary, with whom he had enjoyed a close relationship in the 1950s. The results of their work were formalised under Jay’s supervision in sworn statements which would be used to back the avalanche of writs and court hearings, costing £1 million, which obsessed Maxwell until his death.

Initially, Maxwell tried to prevent the book’s publication in February 1988, at the same time publishing his own version written by Joe Haines. When my book hit the top of the bestseller list, Maxwell sought through individual cajolery and writs to prevent every bookshop in Britain selling the title. Eventually he was successful in this endeavour, but he nevertheless continued to hound me and the publishers by pursuing various writs for libel. Jay’s task was to co-ordinate and supervise the unprecedented legal battle.

By spring 1989, one year after publication, when the first of three publishers had agreed to publish the paperback version only to retreat rather than face the subject’s wrath, Maxwell’s anger was increasing in parallel to the secretly developing insolvency of his empire. His fury had shifted from the book’s accurate description of his unaltered dishonesty to something which in his view was more sinister. He believed that I had become a focus for his enemies and a receptacle of damaging information. Just as he was finalising a deceptive annual financial report for the Maxwell Communication Corporation, of which he was chairman, he embarked upon a new venture to humiliate the book’s publisher and bankrupt its author.

Four lawyers were Maxwell’s principal advisers. Lord Mishcon and Anthony Julius were his solicitors and Richard Rampton QC and Victoria Sharp were the barristers. During their frequent court appearances, they betrayed no hint of doubt about their client’s virtues. On the contrary, they pursued his mission with depressing vigour, commitment and pitilessness.

Their client’s anger had by then increased still further. The book had been published in France and his defamation action there had failed. To his fury, a court had ordered that he pay me FFrs 10,000 in costs. The threat that the book might also be published in his beloved New York galvanised him to resort to more draconian measures.

Maxwell had become convinced, in the words of Stephen Nathan, another barrister hired for advice, that I had ‘compiled (and continued to compile) an extensive record of information concerning Mr Maxwell and has put the distillation of that information on to a computer which he keeps at home’. Maxwell’s source was Frost, who, during his gumshoe expedition around Hampstead, had picked up from an ‘unidentified source’ the notion that my study had become a centre for subversive activities against the Chairman.

Nathan had been asked to advise whether I could be prosecuted for failing to register as a data-user under the Data Protection Act 1984 or, better still, whether Maxwell might approach the Director of Public Prosecutions. The DPP, the Chairman hoped, would direct the police to seize the computer without warning. That course, advised Nathan, would be possible only if Maxwell could persuade the DPP of the allegedly dangerous contents of the computer.

Frustrated by Nathan’s wishy-washy advice, Maxwell ordered Lord Mishcon to seek the seizure of my computer on the orders of a judge under an Anton Piller order. Naturally Jay passed on the instruction to Julius. Such an order, suggested Jay, would enable ‘Bower’s computer records to be seized under warrant, without advance notice being given, therefore without Bower having an opportunity to destroy or conceal such records’. In retrospect, the irony of Maxwell mentioning Anton Piller was manifest. The order, as Mishcon explained, is used to obtain the seizure of documents for the investigation of fraud or systematic dishonesty. And Jay, in passing on Mishcon’s advice to the Chairman in another ‘Intermemo’ on 7 April 1989 headed ‘Bower’s Computer’ and marked ‘Strictly Confidential’, noted mournfully, ‘Legally speaking, this is not (quite) the situation with Bower.’

Mishcon urged his client to adopt the customary course and apply to the court for the computer records. But, he cautioned, ‘Our evidence that these records exist is thin.’ Therefore, advised the peer, ‘I recommend that investigations should continue.’ Hence Maxwell ordered Jay to seek the evidence required, and this was why Jay was inspired to ask the detective to place the scanner at the bottom of my garden. But after receiving Potter’s disappointing news, Jay concluded, ‘It is not really practical to proceed along the lines we discussed.’

That was by no means the end of the battle. Until October 1991, Maxwell regularly held meetings with lawyers and with his personal security staff to propel the battle towards my bankruptcy and his vindication. The readiness of Peter Jay, a journalist and former British ambassador, to function as his willing tool was sadly not unique in Britain or elsewhere. He merely epitomised a cravenness common among a horde of self-important personalities and powerbrokers whose self-esteem was boosted by the Chairman’s attentions and deep purse.

Unfortunately, the sort of campaign directed against my book acted as a disincentive for most newspapers against exposing Maxwell in his lifetime. Many blame Britain’s libel laws and lawyers’ fees for protecting him, yet the law and its expense were not the sole reason for British newspapers’ reluctance or inability to uncover his crimes. More important was the environment in which newspapers now operate.

Few newspaper editors and even fewer proprietors nowadays relish causing discomfort to miscreant powerbrokers. By nature anti-Establishment, the so-called ‘investigative’ reporter finds himself working for newspapers which are increasingly pro-Establishment. Only on celluloid, it seems, does an editor smile when listening to a screaming complainant exposed by his journalists.

Proper journalism, as opposed to straightforward reporting or the columnists’ self-righteous sermonising, is an expensive, frustrating and lonely chore. Often it is unproductive. Even the rarity of success earns the ‘investigative’ journalist only the irksome epitaph of being ‘obsessional’ or ‘dangerous’. The final product is often complicated to read, unentertaining and inconclusive. No major City slicker has ever been brought down merely by newspaper articles. Like the Fraud Squad, financial journalists usually need a crash before they can detect and report upon the real defects. Often, only with hindsight does the crime seem obvious. Even though in Maxwell’s case his propensity to commit a fraud had been obvious since 1954, it was almost impossible for any journalist to produce the evidence contemporaneously.

Moreover, many of those who reported Maxwell’s affairs during the 1980s were only vaguely aware of the details of the Pergamon saga in 1969, when his publishing empire had disintegrated amid suspicions of dishonesty which appeared to have terminated his business life. After three damning DTI reports, no one expected Maxwell’s resurrection. However, the DTI inspectors, having found the evidence of fraud and voiced a memorable phrase about his unfitness to manage a public company, had not directly accused him of criminality. It was the inspectors’ cowardly reluctance to publish their real convictions and the police failure to prosecute which permitted Maxwell during the 1980s, when explaining his life, to distort the record of the Pergamon saga.

Accordingly, by 1987, Buckingham Palace, the City, Westminster and Whitehall had forgotten or forgiven the past. In the year in which Maxwell’s final frauds began, most journalists reflected the prevailing sentiment and were willing to afford him the benefit of the doubt.

To have broken through Maxwell’s barrier required not only a brave inside source who was willing to steal documents but also someone who would risk the Chairman’s inevitable writ. But, unlike in America, whistleblowers are castigated in Britain, where secrecy is a virtue. To break those barriers also required expertise and a lot of money, increasingly unavailable to newspapers and to television. So almost until his end Maxwell enjoyed a relatively favourable press, although journalists were not to blame for the canker’s survival.

The real fault for Maxwell’s undiscovered fraud belongs to the policemen employed in the Serious Fraud Office, to the civil servants, especially in IMRO and the DTI, who are empowered to supervise Britain’s trusts and corporations, and to the accountants at Coopers and Lybrand who were his companies’ auditors. As with most of Britain’s financial scandals, those arrogant, idle and ignorant bureaucrats, having failed in their duties, were not embarrassed nor dismissed, because they were protected by self-imposed anonymity. It was their good fortune that many blamed Britain’s libel laws for the failure to expose Maxwell’s fraud. But that was and remains too easy. Maxwell prospered because hundreds of otherwise intelligent people wilfully suspended any moral judgment and succumbed to their avarice and self-interest. To suggest that much will be learned from Maxwell’s story is to ignore past experience, but his story is an extraordinary fable, not least because only now can one read the final verdict.

ONE The Autopsy – 9 November 1991

The corpse was instantly recognizable. The eye could follow the jet-black hair and bushy eyebrows on the broad Slav head down the huge white torso towards the fat legs. Until four days earlier, the puffy face, recorded thousands of times on celluloid across the world, had been off-white. Now it was an unpleasant dark grey. The body was also disfigured. An incision, 78 cm long, stretched from the neck down the stomach to the crotch. Another incision crossed under the head, from the left shoulder along the collar bone. Firm, black needlework neatly joined the skin to conceal the damage to the deceased’s organs.

Lying on a spotless white sheet in a tiled autopsy room, the corpse was surrounded by eight men and one woman dressed in green smocks. An unusual air of expectancy, even urgency, passed among the living as they stood beneath the fierce light. It was 10.25 on a Saturday night and there was pressure on them to complete their work long before daybreak. Over the past years, thousands of corpses – the victims of the Arab uprising – had passed through that undistinguished stucco building in Tel Aviv. But, for the most part, they had been the remains of anonymous young men killed by bullets, mutilated by bombs or occasionally suffocated by torture.

This cadaver was different. In life, the man had been famous, and in death there was a mystery. Plucked from the Atlantic Ocean off the Canary Islands, he had been flown for burial in Israel. Standing near the corpse for this second autopsy was Dr Iain West, the head of the Department of Forensic Medicine at Guy’s Hospital, London. His hands, encased in rubber gloves, were gently touching the face: ‘He’s been thumped here. That looks genuine. You don’t get that falling just over the edge of a boat. You don’t get this sort of injury.’ West’s Scottish-accented voice sounded aggressive. Retained by the British insurance companies who would have to pay out £21 million if the cause of death were proved to have been accident or murder, he found his adrenalin aroused by a preliminary autopsy report signed two days earlier by Spanish pathologists. After twenty-one years of experience – and 25,000 autopsies – he had concluded that there were no more than two Spanish pathologists who deserved any respect: the remainder were ‘not very good’. The conclusion of Dr Carlos Lopez de Lamela, one of that remainder, that the cause of death was ‘heart failure’ was trite and inconsequential. West was thirsting to find the real cause of death. His first suspicion was murder. Yet he knew that so much of pathology relied upon possibilities or probabilities and not upon certainties. Mysteries often remained unresolved, especially when the evidence was contaminated by incompetence.

The Briton’s position at the autopsy was unusual. Under the insurance companies’ agreement with the Israeli government, he could observe but not actively participate. West regretted that he would not be allowed to follow the contours and patterns of any injuries which might be discovered and privately felt slightly disdainful of his temporary colleague, Dr Yehuda Hiss. He recalled the forty-five-year-old Israeli pathologist – then his junior – learning his craft in Britain in the mid-1980s. He had judged him to be ‘competent’, although unused to the traditional challenges of autopsy reports in Britain. West was nevertheless now gratified to learn that his lack of confidence in the Spaniards was partially shared by Hiss. In the Israeli’s opinion, Dr Lamela’s equivocation about the cause of death was unimpressive.

West watched Hiss dictate his visual observations. Touching the body gently, even sensitively, the Israeli noted small abrasions around the nostrils and rubbed skin under the nose and on the ear, but no signs of fresh epidermal damage anywhere on the head or neck. There were no recently broken bones. Although the body had apparently floated in the sea for up to twelve hours, the skin showed no signs of wrinkling or sunburn. ‘We’ll X-ray the hands and the foot,’ ordered Hiss.

His dictation was interrupted by West: ‘I wonder if they’ve looked at his back?’

‘No, no,’ replied Hiss, going on to note a small scar, thin pubic hair and circumcision.

Again he was interrupted: ‘The teeth are in bad condition.’

‘The dental treatment is poor,’ agreed another Israeli.

‘Very poor’, grunted West, ‘for a man who was so rich.’

‘Are you sure it’s him?’ asked an Israeli. ‘We’d better X-ray the teeth for a dental check.’

‘Well, it looks like him,’ snapped West. ‘The trouble is we’re up against time. He’s being buried tomorrow. I think we’ll take fingerprints.’ Again, he criticized the Spaniards: ‘The fingernails haven’t been cut off. They said they’d done it.’

Midnight passed. It was now the day of the burial. The corpse was turned over. ‘We’ll cut through and wrap it back,’ said West impatiently. The two pathologists had already concurred that the Spanish failure to examine the deceased’s back was a grave omission – it had been a common practice in Britain since the 1930s, as a method of discovering hidden wounds.

There was no sentiment as two scalpels, Hiss’s and an assistant’s, were poised over the vast human mound. None of the doctors contemplated its past: the small baby in the impoverished Czech shtetl or ghetto whose soft back had been rubbed after feeding; or the young man whose muscular back had been hugged by admiring women; or the tycoon whose back five days earlier had been bathed in sunshine on board a luxury yacht worth £23 million. Their scalpels were indiscriminate about emotions. They thought only of the still secret cause of death.

After the scalpels had pierced the skin and sliced through thick, yellow fat on the right side, West’s evident anticipation was initially disappointed: ‘I’m surprised that we didn’t find anything.’ A pattern of bruises was revealed to be only on the surface, the result of slight pressure, but not relevant to the cause of death. More dissections followed, mutilating the body tissue, slitting the fat, carving the flesh inch by inch in the search for the unusual. Minutes later there was a yelp.

‘Do you see that?’ exclaimed Hiss.

‘It’s a massive haematoma!’ gasped West, peering at the discovery. There, nestling among the flesh and muscle in the left shoulder was a large, dark-red blob of congealed blood.

‘Nine and a half by six centimetres,’ dictated Hiss in Hebrew, ‘and about one centimetre thick.’

West prodded the haematoma: ‘There’s a lot of torn muscles – pulled.’ It was those tears which had caused the bleeding.

Here was precisely the critical clue missed by the Spaniards: since there were no suspicious bruises on the skin, they had lazily resisted any probing. Now the new doctors were gazing at violently torn fibres. Yet Hiss was not rushing to the conclusion he sensed was already being favoured by West. ‘The trouble is, it’s also an area where you often hit yourself,’ he observed.

‘It’s not a hit,’ growled West.

There was, they agreed, no pattern of injuries of the kind which usually accompanies murder – no tell-tale grip, kick or punch marks, no small lacerations on the skin which at his age would easily have been inflicted in the course of a struggle or by dragging a heavy, comatose body.