скачать книгу бесплатно

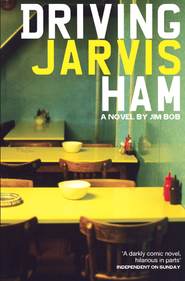

Driving Jarvis Ham

Jim Bob

A brilliantly witty story of unconventional, unwavering, and regularly exasperating friendship.Meet Jarvis Ham: tea-room assistant, diarist, lift-cadger, Princess Di fan, secret alcoholic, and relentless seeker of fame. Jarvis may be an all-round irritant, but he’s harmless, and deep down, you know, he’s got a heart of gold. Hasn’t he?As his oldest (and only) friend reflects on his life with Jarvis Ham – infatuations, questionable hairstyles, home-made charity singles, reality TV auditions, paedophile alerts at the local swimming baths – he wonders what it would have been like if they had never met. But what are you going to do? He’s a mate. DRIVING JARVIS HAM is a novel for anyone who has ever found themselves looking across at a childhood friend, and wondering why they still know them.

JIM BOB

Driving Jarvis Ham

To Neil, for all the driving

If you’re reading this it probably means I’m not dead.

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u2cb16101-9b2d-557a-af5f-fc55d970d3b7)

Dedication (#u1a29e73e-77c4-584c-8bad-df7f4bb8e469)

Part One (#u0fa957ab-79cb-5fcb-8d0e-18ef94ab04e1)

Jarvis Goes to Drama Club (#u089f048c-ed46-5c7f-bec6-09a41bbf198c)

Jarvis Gets a Girlfriend (#uab4022d7-60a5-5b74-9edd-e1bb0569641f)

Just This One Last Lift and That'll be It (#litres_trial_promo)

Jarvis Goes to London (#litres_trial_promo)

Jarvis Learns to Swim (#litres_trial_promo)

August 31st 1997 (#litres_trial_promo)

Simon Aveton (#litres_trial_promo)

Jarvis Reinvents Himself (#litres_trial_promo)

Dean Bantham and Shane Prior (#litres_trial_promo)

Jarvis Gives Something Back (#litres_trial_promo)

Mark Halwell (#litres_trial_promo)

Jarvis Buries a Millennium Time Capsule (#litres_trial_promo)

Lloyd Morleigh (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Ham Alone (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise for Driving Jarvis Ham (#litres_trial_promo)

By the same author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

‘Would you drink a pint of your own piss?’

‘Yes I would.’

‘Eat some shit?’

‘No problem.’

‘How about someone else’s piss or shit?’

‘Yes.’

‘Would you toss a man off?’

‘Of course I would.’

‘An old man?’

‘Yes.’

‘That old man who used to sit outside our school drinking white spirit?’

‘Yes.’

‘While your grandmother was watching?’

‘Yep.’

‘Would you punch a child?’

‘Uh huh.’

A car game.

To pass the hours between service station stops and hard shoulder/weak bladder toilet breaks. To lessen the boredom that is the drive up from Devon to London with Jarvis Ham as a passenger.

The Million Pound Game is a hypothetical question game, like what would you do if you won the lottery or if you had three minutes to live or you were invisible.

Jarvis would always win the Million Pound Game. He would have tossed off a tramp while his nan watched. For a million pounds Jarvis would eat shit and drink piss. He’d punch a child. He’d kick the kid and stamp on its fingers while it was on the floor. Let’s get this straight. Jarvis Ham would do it for less than a million. He’d do it for no money at all. Jarvis would do it for the fame.

Jarvis once told me that he had two big ambitions. Number one was that he wanted his life to become so unbearable, with all the fans and the stalkers and the photographers camped outside his house all night that he’d have to fake his own death. His other big ambition was to get shot dead by an obsessive Jarvis Ham fan.

True story.

Of course, if Jarvis did hit that kid I’d get two hundred grand. Twenty per cent of the million that Jarvis won for eating his own faeces or letting his grandmother watch him milk a tramp would be mine. I’d be a twenty per cent accessory to whatever filth or depravity Jarvis Ham put himself through to become a famous millionaire. As Jarvis Ham’s manager: the punched kid, the poo, the wee, the perverted sex with the homeless, everything that I’m going to tell you about. It’s technically one-fifth my fault.

PART ONE

The Ham and Hams Teahouse is one of five shops in a short row of businesses at the top of Fore Street. Inside it looks like an episode of the Antiques Roadshow. None of the furniture matches. The chairs don’t go with the tables; teacups sit uncomfortably on odd saucers. Knives, forks, spoons and sugar tongs all come from different cutlery sets. If it actually had been an episode of the Antiques Roadshow, the expert would have said, ‘If only you had the full set, I think, for insurance purposes, you would have been looking at fifty to a hundred thousand pounds. Unfortunately, what you have here is worth fuck all.’

The Ham and Hams Teahouse didn’t care. Variety was its spice of life. The leaflets on the counter next to the big old Kerching! style till boasted about it: The Ham and Hams Teahouse is not Starbucks, the leaflets proclaimed above a drawing of an impossible cake.

Next to the counter there’s a floor to ceiling glass cabinet that is a shrine to sugar. A cake castle. Half a dozen glass shelves packed with Bakewell tarts and carrot cakes, with sticky date, cream and treacle cakes. Big and high cakes topped with thick cream and fresh strawberries, looking like something the Queen might wear on the top of her head for the State Opening of Parliament. There are pineapple upside down cakes, victoria sponge up the right way cakes and tiramisu to die for. In fact, nut allergy sufferers have been known to play anaphylaxis roulette with a slice of chocolate and hazelnut panforte from the Ham and Hams Teahouse. From up to half a mile away, if you stood very still and quiet, you could hear customers licking their lips and saying ‘yum yum’.

The flag of the day in the postage stamp of lawn in front of the Ham and Hams this morning was the flag of the Cook Islands: a blue background with a Union Jack in the top left hand corner and a circle of white stars to the right. There was hardly any wind and the flag was barely moving. A middle-aged couple dressed in shorts and matching sweatshirts sat beneath a pub umbrella at one of the two tables outside the Ham and Hams, they were eating the fluffiest scrambled eggs you’ve ever seen, served on the toastiest toast of all time. I parked the car and walked towards the teahouse.

I could see Jarvis through the window. He was wearing an apron with a picture of a big fat cartoon plum on it – no comment. He saw me and held up two fingers, he mouthed the words, ‘two minutes’ and carried on serving tea and cakes to the tourists. I stood in the street and waited.

A newly blue-rinsed old lady came out of the hairdressers next door to the Ham and Hams. She smiled and said ‘hello’ in that Devon friendly way that freaks out visitors from London who think it’s some kind of a trick or a hidden camera show stunt. I smiled back.

‘Lovely day for it,’ the blue-rinsed lady said.

It was.

There were no paparazzi outside the Ham and Hams Teahouse this morning. No photographers on stepladders trying to get pictures of Jarvis through the window. Nobody jockeyed and jostled for position shouting ‘Jarvis! Jarvis! Over here!’ There’d be no warning of flash photography on the lunchtime news. Not today. The epileptics had nothing to worry about just yet.

The bell above the door of the Ham and Hams Teahouse tinkled and Jarvis walked out and straight past me like I was invisible. He was still wearing his apron. He headed towards my car. I sighed and aimed the key fob over his head, there was a beep beep and a flash of headlights.

‘Don’t cab me Jarvis,’ I called out after him, and then more to myself, ‘I’m not your chauffeur.’ But he was already halfway into the back seat and closing the door. By the time I reached the car he’d already be snoring. He could fall asleep almost instantly like that, like he had a standby switch.

While Jarvis slept in the back I’d obey the signs and drive him carefully through the village, and as I left the village another sign would thank me for having done so. I’d drive carefully as requested through all the other villages and small towns on the way to the A38 – although I’d ignore the sign as I entered one village that someone had altered with white paint or Tipp-Ex to read PLEASE D I E CAREFULLY. I drove on through Yealmpton and Yealmbridge, Ermington and Modbury, seeing signs along the way for Brixton and Kingston: strangely West Indian sounding names for such very white places.

Turning onto the A38, I’d put my foot down. I could now drive less carefully. Make a mobile phone call, take both hands off the wheel. Open a bag of crisps, read a newspaper, start a 500-piece jigsaw puzzle of the Houses of Parliament.

I’d search for a radio station that wasn’t playing sincere British indie guitar music, but I wouldn’t find one and after going round the FM waveband in circles a few times I’d settle on some local news and an overlong, inaccurate weather forecast. I’d presume the weather forecaster was broadcasting from a windowless basement after travelling to work blindfolded in the back of a van. I could have told him it was actually an average day for the time of year. For any time of year really; some bright sunshine, with occasional Simpsons clouds breaking up the otherwise pant blue sky. When we reached the outskirts of Exeter, just before we drove onto the M5 for the few miles of motorway that would take us to the A30 and the A303, it would rain. The radio weatherman was right there at least.

I’d look in the rear-view mirror at the sleeping Jarvis Ham. His chubby face flattened against the car window, his lips and nose distorted like a boxer captured in slow motion after a massive right hook. I’d try to work out what it was that made me not Jarvis’s chauffeur. I just couldn’t put my driving gloved finger on it. He always sat in the back. On all the many times I’d given him lifts I’d never once heard him call shotgun.

Giving Jarvis this latest lift from the South Hams up to London was going to be a more uncomfortable journey than usual for me, and maybe for him too. Not because the car was rubbish or because the roads were particularly bumpy. Far from it. The gearbox and the tyres were brand-new and the roads beneath them were smooth. The reason for my and perhaps Jarvis’s discomfort was that we both had a secret we’d been keeping from one another. Jarvis’s secret was that he’d been writing a diary. My secret was that I’d been reading it.

MARCH 31st 1972

Where were you born? Not the town or the country. The actual place of your birth, the venue? A hospital I bet. Or at home. Like Diana. She was born in Park House, Sandringham late in the afternoon on the first of July in 1961. She weighed a wonderful 7lb 12oz. I was born in a museum. And not just any old museum either. No way Jose. I was born in the British Museum. The British Museum. I was born in the British Museum! Imagine that. Mental. How brilliant was my birth. Correct. Very brilliant. And also, I almost forgot. It was Good Friday. How good a Friday is that? Correct again. Very good. More like Brilliant Friday. Very brilliant Friday. I don’t know how much I weighed and don’t say that you bet it was a lot or else.

Okay, so it’s not exactly Samuel Pepys (although Jarvis will eventually bury a cheese during a fire).

It’s not even a diary really. Not in the conventional sense. This first entry for example, can I call it an entry, even though I’ve just said it’s not a diary, otherwise we’ll be here all day? This first entry was written in black felt tip pen on the first page of a big purple scrapbook. The newspaper cutting about the Tutankhamun exhibition and more importantly about Jarvis Ham’s birth was glued to the front cover. On the next page of the scrapbook was the second diary entry. It’s another Tutankhamun one. It’s still not Samuel Pepys. Six years have passed. There’s a title.

JARVIS HAM – BOY ACTOR

JUNE 20th 1978

My first ever acting role was the lead in our primary school’s production of Tutankhamun the Boy King. I can’t remember the story. Obviously. I was only six. I do remember that the rest of the class were all dressed as my slaves and they carried me into the dinner hall on a huge golden throne. I had to wave at the audience below me as they all cheered and applauded. My wave was like the wave the Queen Mother does. The Mayor and his wife were there in the audience and probably somebody from the local council. I was six, I can’t remember all the details! All the mums and dads were there too and the teachers and headmaster and a vicar (a guess). I loved it when everybody was clapping and cheering. How do I remember that then, you’re asking I bet. I don’t know, but I do. I won a prize for my acting. Not an Oscar (not yet). I looked exactly like the real Boy King Tutankhamun did, even though I was six and he was nine. I hadn’t trained at RADA or anything. I was only six. Have I made that clear? But, even though I was only six I definitely remember that it was brilliant. Very brilliant.

King Tut.

I got him that gig.

We were six years – although you probably already know that – old when our teacher Miss – can’t remember her name – asked the class who would like to play the lead role. As she scanned the classroom for a raised hand I panicked. I thought she might not find a volunteer and pick me at random for the role.

‘Jarvis, Miss!’ I shouted out, pointing at Jarvis sat at the desk next to mine. The whole class turned to look at him as Miss thing thought for a moment, perhaps about how the cute kids always got to play the princes and princesses and maybe it was time to give the less fortunate uglier fatter balloon-faced kids a chance.

Why did the classroom seating have to be arranged alphabetically on our first day at school? Why couldn’t we have been seated boy/girl/boy/girl instead? Then I might have been sat next to sweet freckle-faced Suzie Barnado. Who knows, perhaps we’d be married now. With a houseful of sweet freckle-faced kids. Or why couldn’t I have just had a different surname? A name with its initial letter earlier or later in the alphabet. My stupid parents and their idiotic ancestors. If my surname had begun with an N or a P, I might have been sat next to Martin O’Brien on my first day at school. Martin O’Brien won three hundred grand on the lottery a few months ago. It was on the front page of the local paper. If my name had begun with an N or a P, I might have ended up managing Martin O’Brien instead of Jarvis and Martin would have had to give me £60,000 of his lottery cash.

The point is. I wouldn’t have been sat next to Jarvis Ham when the teacher was looking for her boy king and we could all end this story right here and get on with our lives.

‘Jarvis? Would you like to play the part of the Boy King?’ Miss I-can’t-remember-what-her-name-was said. She might as well have stood outside the school gates at home time and given Jarvis a free sample of heroin or crack cocaine.

Tutankhamun the Boy King would be Jarvis Ham’s gateway drug. Here’s my review of the show:

There was an American actor and comic named Victor Buono. He played the comic villain King Tut in the 1960s television show Batman. Look him up on the Internet. I hardly remember Jarvis’s King Tut performance, as I was only six myself, but for the sake of this anecdote I’m going to pretend that I remember the six-year-old Jarvis Ham’s King Tut being a lot more like that thirty-year-old plump and slightly camp actor’s version of King Tut than the ancient Egyptian boy child royalty that Jarvis was attempting to portray. I do remember that Jarvis had a beard that his mother had made from the inside tube of a toilet roll; it was covered in black and gold sticky paper and glued to his chin. His mother had also made the rest of his costume. She’d cut the top off a gold cocktail dress and made a headdress out of a tea towel that was held in place with a hair band wrapped in silver foil on top of her son’s royal balloon head.

The rest of the class, including me, carried Jarvis into the dinner hall on a golden throne: made from the headmaster’s office chair, covered in gold paper and decorated with hieroglyphics. It weighed a fucking ton.

It was not very brilliant.

After the performance was over our teacher congratulated us all for doing so well and she gave Jarvis a bag of Jelly Tots for his starring role. As we waited for our parents to pick us up and take us home Jarvis told me to hold my hand out and he poured six of the sugar covered jelly sweets into it.

My management commission.

Mister Twenty Per Cent.

The rest of the scrapbook was blank. What a waste of a good scrapbook. I suppose Jarvis might have started out with good scrapbook keeping intentions and then maybe he ran out of glue, or he lost his scissors. Or was this the beginning and end of the diary of Jarvis Ham? Just these two brief entries about the ancient Egyptian monarchy? Why couldn’t I have been sat next to sweet freckle-faced Suzie Barnado? I could have been reading her diary. I bet Suzie had some filthy secrets.

Then I found this shoebox:

I climbed into the car, adjusted the rear-view mirror and looked at Jarvis fast asleep in the back; his face squashed against the window and the start of a dribble slowly chasing a raindrop down the glass. Not really, it wasn’t raining, I’m just trying to insert a bit of poetry into the story. God knows it’s going to need it. He had the seatbelt pulled across his body but not fastened. He said it made him feel sick when it was fastened.

There was a new smell in the car. I think you’d call it funky, funkier than James Brown. I turned my head to look. Jarvis had taken his shoes off. They were on the back seat next to his big fat plum apron.

These shoes:

I thought about the shoebox and what I’d found inside it. There were some other newspaper cuttings. There were notepads and loose pieces of paper, stuff written on the backs of flyers and takeaway menus. I found a couple of photographs and some drawings, cinema tickets and hairdressing appointment cards and even one or two actual proper diaries. The shoebox was inside this huge old brown leather suitcase:

The suitcase had once been owned by an incredibly famous stage actor that I’d never heard of. Jarvis’s father had bought it at an auction for his son’s eighteenth birthday. It was covered in stickers of places in the world the actor had visited and the plays and musicals he’d appeared in while he was there.

In the suitcase with the shoebox there were two videocassettes, an Oscar statue, more notepads and books and various other bits of crap. It’s this collection of junk that I’m calling Jarvis Ham’s diary. It’s more of a boot sale than a diary. A boot sale that Jarvis had been secretly keeping and I’d been secretly reading.