Полная версия:

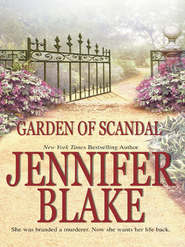

Garden Of Scandal

It wasn’t so easy to shut away the memory of the afternoon before.

If she closed her eyes, Laurel could still feel Alec’s arms around her, feel the disturbing moment when she had pressed against the hard warmth of his body. It had been like standing at the center of a lightning strike, caught in the flare of white-hot heat, blinding light and searing power. Nothing had prepared her for the conflagration, or for the rush of need that poured through her in response. She had been stunned, held immobile by feelings so long repressed, she had forgotten they had existed. If she had ever known them.

She wasn’t sure she had. Even in the days when she was first married, when loving was so strange and new, she had not felt so fervid or so uncertain of her own responses, her own will.

No. She wouldn’t think about it. She would forget she had ever touched Alec Stanton. And she would pray to high heaven that he did the same.

“Full of passion, secrets, taboos and fear, Garden of Scandal will pull you in from the start as you work to unwind the treachery and experience the sizzle.”

—Romantic Times

GARDEN OF SCANDAL

JENNIFER BLAKE

For my husband, Jerry, with loving appreciation

for the man who, at our home known as

Sweet Briar, constructed the real garden of antique

roses that provided the inspiration for this book.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

1

She tore out of the lighted house like a banshee. Screaming in a shatteringly clear soprano above the growling of the great black German shepherd, she skimmed across the front porch. She was halfway down the high steps before the ancient wooden screen door slammed shut after her.

Part harridan, part avenging Valkyrie, she raced toward him wearing a nightgown with light streaming through it from behind. Her long hair shifted and whipped around her, shimmering silver-gold in the moonlight. Her feet barely touched the ground. Fleet, slender, with the pure lines of her face twisted in concern, she was the most fascinating thing Alec Stanton had ever laid eyes on.

“Sticks! Here, boy!” she called out as she ducked under the low-hanging limb of a magnolia, dodged the rambling branches of a spirea. Her gaze was riveted on the dog standing ferocious guard on the mossy brick walk.

The German shepherd growled, a ragged warning that resonated deep in his massive chest. His eyes never left Alec. He lifted his ruff, baring his teeth in challenge. As the woman came nearer, the animal moved protectively to block her path with his body.

“What is it, boy? What have you got cornered?” Her voice was anxious but not fearful as she slowed her pace. Then she saw Alec.

She stopped so quickly that her hair swirled forward, covering her arms like a cape of captured moonbeams. Her hands clenched into fists. Her eyes widened. She squared her shoulders, then stood so motionless she might have been turned into pale, warm marble.

The dog ceased to exist for Alec. And he forgot why he was there amid the tangled briers, vines and overgrown shrubbery that were the front garden of the Steamboat Gothic mansion known as Ivywild. Moving like a man in a daze, he stepped forward out of the night.

The German shepherd launched off his haunches in attack. Eighty pounds of hard muscle and death, he sprang straight for Alec’s throat.

“Down! Down, Sticks!” The woman’s shout mingled with the dog’s snarl. Yet there was no hope the animal would, or could, obey.

Alec’s instinct and training kicked in. He spun away as the dog hit him, moving with the force of the assault, flowing with it to lessen the impact even as he snatched the dog’s huge black head in an iron grip. Finding the pressure points, Alec drove his thumbs against them. He sank to his knees, still turning, flexing hard muscles as he came about in a full circle.

It was over in a moment. When Alec rose, the animal was stretched out, limp and barely breathing, on the walk between him and the woman.

She moaned and dropped to the ground, gathering the lolling head of her guard dog into her lap. Holding tight, she rocked back and forth.

“He’ll be all right,” Alec said with stringent softness.

She made no reply. Then he heard the catch in her breathing as the dog stirred, whimpered.

Abruptly, she looked up with the wetness of tears glittering in her eyes. “You might have killed him!”

“If I’d wanted to kill him he’d be dead. I just put him out for a few minutes while we get things cleared up here.” Alec could have pointed out that her precious Sticks might have crushed his throat, but it didn’t seem worth the effort.

Her fingers sank into the dog’s coat, holding him closer. “You’re on private property. I want you off in the next two seconds or I call the police. Is that clear enough for you?”

This was not the way things were supposed to go. He had meant to knock politely, then stand outside on the porch while he spoke his piece. He hadn’t expected to feel his heart squeezed in a breath-catching vise at the sight of a woman’s form in a whisper-thin nightgown. He had never dreamed it could happen—not to him, and especially not here with this woman. It was too unexpected for comfort, much less acceptance.

Putting her pet out cold was not a good start, no matter what he had in mind. “I’m sorry if I hurt your dog,” he said.

“Oh, yes, I can tell!” The look she gave him was scathing.

“He shouldn’t have attacked.”

“He was just—He thought I needed protecting.”

It was entirely possible the dog had been right. Wary and off-balance, Alec tried again, looking for some kind of stable ground. “You’re Mrs. Bancroft, Laurel Bancroft?”

“What of it?”

“I…wanted to talk to you.” That had been his original purpose. Things had changed. For what good it would do him.

She didn’t give an inch. “I can’t imagine we have anything to discuss.”

“The lady who keeps house for you, Maisie Warfield, is a good friend of my grandmother’s. She said you need help clearing this jungle of a garden, that it had more or less gotten away from you since your husband died.” His grandmother had said a great deal more. He should have paid attention, he thought, as he added, “I have a little experience with that kind of work.”

She watched him for several seconds, her expression intently appraising. Then she said in disbelief, “You’re Miss Callie’s grandson?”

Stung by the amazement in her tone, he made his agreement short.

“You’re no gardener!”

He shook his head. “Engineer. But I worked as a yardman to put myself through school.” He gave the words a hint of an edge to let her know he didn’t care to be prejudged.

“I can’t afford an engineer,” she said baldly.

He considered telling her she could have his services for free—any service she wanted, any time. But that wouldn’t work, and he still had sense enough, just, to know it. “Manual labor at the going rate is what I’m offering.”

“Why?”

The single word hung between them for a moment as Sticks lifted his head and shook himself before turning to lie on his belly. The dog looked up at Alec, then away again, as if embarrassed. Whining, he crawled forward a few inches to lick his mistress’s hand in apology.

Watching the animal with a hot sensation very like envy, or even jealousy, pervading his skull, Alec said, “A lot of reasons, but let’s just say I need the money.”

“You can get a better job anywhere else.”

“I need to hang loose, not be too tied down.”

Her gaze was concentrated as she smoothed her hand over the dog’s head in a gesture of comfort, then got to her feet. “Because you don’t like wearing a suit? Or is it your brother?”

“Both.”

She knew all about him and Gregory; he might have guessed. That was one of the glories of small towns. Also their major pain in the backside.

He allowed his eyes to glide over her, then away. But he could still see the slim moon-silvered shape of her burning in his mind like a candle flame. He swallowed hard.

“If you expect me to be sympathetic—” she began.

“No.” He made an abrupt, slicing gesture. “Sympathy is something we don’t need. Either of us.”

She stiffened. “My situation has nothing to do with you!”

He looked back at her, speaking gently as he tilted his head. “I meant my brother and myself. Though I guess it would be safe to include you in it, too.”

She didn’t answer; only stood staring up at him. The moonlight washed across her features, highlighting the scrubbed freshness of her skin that was so translucent it responded to every shift of emotion beneath its surface. He could see the blue of her eyes, wine-dark as the Aegean Sea, yet clear, as if she knew more than she wanted to about people. Particularly men and their baser urges.

His were the basest of the base.

She had just come from a shower, he thought; he could smell the fresh soap and clean-woman scent of her. It was as potent an aphrodisiac as any he had ever imagined. He ached with it, hardening beyond comprehension from no more than sharing the same warm night air.

She seemed fragile, yet there was inner strength in the way she stood up to him, a stranger in the dark. She was real—a little shy, but self-possessed to the point of being regal. She wasn’t perfect; there were fine lines at the corners of her eyes, and her upper lip was not quite as full as the lower. She was almost perfect, though, so close to beautiful that it was nearly impossible to look away from her.

It wouldn’t do. She’d never have anything to do with Callie Stanton’s California-hippie grandson. To her, he must look like a kid with more brawn than brains. It was downright funny, if you thought about it. Only he wasn’t laughing.

Laurel shivered a little under the impact of Alec Stanton’s gaze. His eyes were so black, the pupils expanding, driving out all color, leaving still, dark pools of consideration. He was tall and broad, a solid presence holding back the night that crowded around them. She knew instinctively he would be more than able to protect her from whatever might be lurking in the darkness. Yet she did not feel safe.

He was too big, too strong, too fast. The defense he had made against poor Sticks was some dangerously competent form of martial arts; she knew enough to recognize that much even if she didn’t know what to call it. Beyond these things, he was far too exotic with his long black hair tied back in a ponytail with a leather thong, the dark ambush of his thick brows and lashes in the strong square of his face, and the silver slash of an earring shaped like a lightning bolt that was fastened in his left ear.

He was dressed entirely in black: boots, jeans, and a sleeveless T-shirt that emphasized the sculpted muscles of his torso. The skimpy shirt also exposed the multicolored stain of an intricate tattoo on his left shoulder, dimly recognizable as a dragon winding across his pectoral and around his upper arm.

As she avoided his black gaze, her eyes flickered over the tattoo, then back again. Her fingers tingled, and she curled them tighter into her palm against the sudden impulse to touch the dragon, stroke the warmth and smoothness of its—his—skin and feel the power of the muscles that glided beneath the painted design. If she tried, she might be able to span the beast with her spread hand, feeling its heartbeat under her palm where the pumping heart of the man lay beneath the wall of his chest.

She drew a sharp breath, snatching her mind from that image as if backing away from a hot stove. She must be crazy. At just over forty-one, she was at least ten years older than he was, maybe a little more.

She had been alone too long, that much was plain. She had grown so used to her solitude and isolation here at Ivywild that she had come flying out of the house in nothing more than her nightgown. Worse than that, she was having wild fantasies simply because she was alone with an attractive man. Definitely, she was losing it.

The warm spring night pressed against her, as if driving her toward the man in front of her. She could smell the wafting fragrance of magnolia blossoms from the tree that loomed above them. The chorus of night insects was a quiet and endless appassionato, an echo of the feelings that sang through her.

At her feet, Sticks struggled upright, then stepped forward to press against her knee. The movement was a welcome release from the curious constraint that held her.

“Look,” she said abruptly, her voice more husky than she intended. “All I had in mind was hiring some older man to cut down a few trees, hack back the brush, maybe dig a rose bed or two—”

He cut across her words in incisive tones. “I can do twice as much in half the time.”

“I’m sure you could, but the point is—”

“The point is you’re afraid of me. I don’t suit the notions of backward, provincial Hillsboro, Louisiana, about how a man should look. I’m not your average redneck—crew-cut and squeaky clean, with nothing on his mind except fishing, hunting and drinking beer. Or at least, nothing he can share with a woman. I don’t fit.” His voice softened. “But then neither do you, Laurel Bancroft.”

Her lips tightened before she opened them to speak. “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Don’t you?”

The smile that accompanied his inquiry lasted only an instant. Yet the brief movement of his mouth altered the hard planes and angles of his face, giving him the devastating attraction of a dark angel. There was piercing sweetness in it, and limitless understanding. It saluted her independence even as it deplored it, applauded her courage in spite of her intransigence. It plumbed her loneliness, offered comfort, promised surcease.

Then it was gone. She fought the chill depression that moved over her in its wake. And lost.

On a deep breath, she said, “That isn’t it—or at least I’d like to think I’m not so petty. But I don’t need any more problems right now.”

“You need help and I need money. We’re a natural.” His words were even, an explanation rather than an appeal.

She flung out a hand in exasperation. “It isn’t that simple!”

“Not quite. My brother has cancer in the final stages. Did you know that? I took unpaid leave from the firm where I work in L.A. to come visit Grannie Callie with him. Now he wants to stay. Good home-cooked food and quiet living may help or may not, but at least it’s worth the chance. Still, I’ll be damned if I’ll live off my grandmother’s charity. I could get a more permanent—not to mention better paying—job, yes. But I’d have to be away all day, and that’s not what I need. Your place is close, the work shouldn’t be too confining. I’m a fast worker, I get the job done and I’m not too proud to follow orders. I know a rose from a rutabaga, and I can lay brick, pipe water, whatever it takes. What more do you want?”

What more, indeed? Nothing, except to listen, endlessly, to the deep, steady timbre of his voice. Which was reason enough to be wary.

“It’s just a small project,” she said. “I might install a little fountain in the middle of the roses after things are cleared away, but it’s not really worth your time, much less your skill.”

His smile came again, warming her, enticing her against her will. “Neither are worth all that much just now. They’ll be worth even less if you turn me down.”

“I don’t think…”

“Tell you what,” he said, easing forward. “I’ll work the first day for free. If you decide I’m no use to you, that’s the end of it. If you like what I’ve done, we’ll take it from there.”

“I can’t let you do that,” she said in protest.

“A fair trial, that’s all I ask. Starting at eight in the morning. What do you say?”

She was definitely crazy, because the whole thing was beginning to sound almost reasonable. What was the difference between hiring him or old man Pender down the road, or even young Randy Nott who did odd jobs for her mother-in-law? This man would be hired help, a strong back and pair of able arms. Probably more than able, but she wouldn’t think about that. A couple of days, maybe a week, and then he would be gone.

In sudden decision, she said, “Make it seven, to get as much done as possible before it gets too hot.”

“You’re the boss.”

Somehow, she didn’t feel like it.

He nodded once, then moved away, melting into the darkness along the overgrown path toward the drive. After a moment, Laurel heard the low rumble of a motorcycle being kicked into life. Then he zoomed off in a blast of power. The noise faded and the night was still again.

A shiver moved over her in spite of the warmth of the evening. She clasped her arms around her, holding tight. Sticks looked up, whining, as he picked up on her disturbance.

“What do you think, boy?” she asked, the words barely above a whisper. “Did I make a mistake?”

The dog gave a halfhearted wag of his tail as he stared in the direction Alec Stanton had gone.

She sighed and closed her eyes. “I thought so.”

Her new hired hand was on time the next morning—Laurel had to give him that much. She had barely pulled on her old jeans and faded yellow T-shirt when she heard his bike turn in at the drive.

Maisie Warfield, her housekeeper, hadn’t arrived yet, since she always had to get her “old man”—as she called her husband who was nearing retirement age—off to work before she could show up. Rather than waiting for Alec Stanton to come to the door and twist the old-fashioned doorbell, Laurel picked up her sneakers and moved in her sock feet toward the side entrance. At least she didn’t have to worry about Sticks. He had spent the night on the screened back veranda and was still shut up out there.

Alec Stanton was not on the drive where his bright red Harley-Davidson leaned, looking as out of place in front of the old, late-Victorian house as a ladybug on the hem of an ancient lace dress. Nor was he in the tangled front garden. However, a ripping, shredding sound led her to the side of the house. He was already at work there, tearing a clinging green curtain of smilax and Virginia creeper away from the overlap siding.

He looked around at her approach. His nod of greeting was brief before he spoke. “The whole place needs painting, though I can see at least a dozen boards that should be replaced first. You’ll lose more if you don’t protect them soon.”

“I know,” she said shortly.

“I could—”

“I can take care of it,” she said, cutting off the offer he was about to make. “You’re here for the garden.”

He yanked down a long streamer of smilax and let it fall, leaving it to be dug up by the roots later. Stripping off his gloves, he tucked them into the waistband of his jeans. He ran a critical eye over the house, which loomed above them, with its balustraded verandas that were rounded on each end in the style of a steamboat, its gingerbread work attached to the slender columns like ice-covered spiderwebs, and the conical tower set into the roofline. “It’s a grand old place,” he said. “It would be a shame to let it fall into ruin.”

“I don’t intend to,” she answered tartly. “Now, if you’ll…”

“Your husband’s old family home, I think Grannie said. How did you wind up with it?”

“Nobody else wanted it.”

That was the exact truth, she thought. The place had been the next thing to abandoned when she first saw it. Her husband’s mother, Sadie Bancroft, had moved out not long after her husband left her back in the sixties. His sister Zelda had no interest in it; she’d had more than enough of the big barn of a place as a child and couldn’t comprehend why Laurel had begged to buy it from the family after she and Howard were married. Even Howard had grumbled about the upkeep and often talked of trading it in for a small, neat ranch-style house during the fifteen years they were married. But that was all it had been—talk.

“It’s mighty big for one person.”

“I like big,” Laurel said and felt a sudden flush sweep over her face for no reason that made any sense. Or she hoped that it didn’t, although that seemed doubtful, considering the ghost of a smile hovering at one corner of Alec Stanton’s mouth.

“Where shall I start?”

“What?”

He tilted his head. “You were going to tell me where to start to work.”

“Yes. Yes, of course,” she said and spun around, leading the way toward the front garden.

She had meant to help him, in part to be on hand to point out what she wanted to keep and what needed to go. She soon saw that it was unnecessary. He knew his plants and shrubs; his time as a yardman had been put to good use. He was also efficient. He didn’t start work until he had checked out the tools in the shed behind the detached garage, then oiled and sharpened them.

“You could use a new pair of hedge shears,” he suggested as he ran a callused thumb along the edge of a wide blade. “It would make your job around here a lot easier.”

He was right, and she knew it. “I’ll tell Maisie to pick them up next time she goes into town.”

“You’re also out of gas for the lawn mower.”

“She can get that, too.”

He studied her for a moment, his eyes as dark and fathomless as obsidian. “You know you have a flat on your car? And the rest of the tires are so dry-rotted you’d be lucky to get out of the driveway on them.”

“I don’t go out much,” she said, avoiding his gaze.

“You don’t go at all, to hear Grannie tell it—haven’t left this place in ages. All you do is read and make clay pots in the shed out behind the garage. Why is that?”

“No reason. I just prefer my own company.” She gave him a cool look before she turned away. “I’ll be in the house if you need anything.”

To retreat was instinctive self-protection, that was all. She didn’t have to explain herself. Certainly it was none of this man’s business whether she went out or stayed home, worked with her pottery or flew to the moon on a broomstick. Nor did she need someone watching her, giving unasked-for advice, prying into her life. She would pay him for what he did today, regardless of what he had said, then send him on his way. She had gotten along without Alec Stanton before he came, and she could get along without him when he was gone.

As the day advanced, however, it could not be denied that he was making progress. He cut away dozens of pine and sassafras saplings from the old fence enclosure, exposing the unpainted pickets almost all the way across the front of the garden. He rescued and pruned the Russell’s Cottage Rose in the corner, tearing out a head-high pile of honeysuckle vines in the process. An arbor and garden bench of weathered cypress were unearthed from a covering of wild grapevines. And the debris from his efforts was thrown into a pile that made a slow-burning green bonfire. The gray pall of smoke rose high enough to cross the face of the noonday sun.

Laurel tried not to watch him. Yet against her best intentions it seemed everything she did took her near the front windows of the house. It was only natural to look out. A perfectly ordinary impulse. That was all.

He had removed his shirt in the middle of the morning. A sheen of perspiration gilded the sun-bronzed expanse of his back, shimmering with his movements, while dust and bits of dried leaves stuck to the corded muscles of his arms. The soft hair on his chest glinted like damp velvet, making a conduit for the trickling sweat that crept down the washboard-like ridges of his abdomen to dampen the waist of his jeans. He was hot and sweaty and dirty and magnificent. And she disliked him intensely for making her aware of it.