скачать книгу бесплатно

SOMETHING SWEET

RHUBARB RICOTTA PUDDING (BY WAY OF CANNOLI)

MAMA’S SIMPLE CUSTARD

CAROLINA RICE PUDDING

LEMON COOKIES

FARRO BISCOTTI WITH MANDARIN, ALMOND, AND ANISE

APPLE CAKE

SEASONAL FRUIT CROSTATA

MY FAVORITE SPONGE CAKE

THREE ITALIAN ICES: CHOCOLATE, NUTMEG, AND LEMON

CONVERSION TABLES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ALPHABETICAL LIST OF RECIPES

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

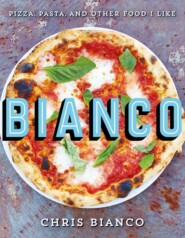

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_8f4017f8-5837-5fa8-8123-20a1fd3b83ef)

The only thing stranger than me writing a book is the idea that anyone would read it. Whether you bought this, stole it, or received it as a gift that you plan to regift, thank you.

If you told me back in 1988, when I first opened Pizzeria Bianco in the back of a Phoenix supermarket, that anyone would ever give a shit about anything I had to say, I would have said, “Sure! And maybe I’ll have a two-way wrist radio like Dick Tracy too! Get the fuck outta here.”

But here I am, almost thirty years later, with a head of hair that is more salt than pepper, almost a real grown-up, married to my best friend, with two beautiful kids and friends and family who I love beyond my ability to articulate. These are my riches, and any successes I may have outside of these pale by comparison.

Love brought me to the table and helped me stumble through the kitchen. I watched as my mom, aunts, and grandmothers made something delicious, and I watched how people responded to it. How I responded to it. It was an expression of love and, though I didn’t know it then, I wanted to be a part of it.

Knowing where our food comes from is as important as knowing where we come from. What we eat has history, purpose, and value. The choices we make affect our bodies and our planet. None of this was on my radar when I was a kid ironing a foil-wrapped grilled cheese sandwich after school, but now it colors everything I do. We need only submit to nature’s perfection and from there imagine the possibilities. An heirloom apple hanging heavy on a crisp autumn day might need only a rub on your shirtsleeve to illuminate its perfection.

My hope is that this book can help you to appreciate how much you already know. A delicious pizza is no more mysterious or magical than the omelettes you make on Sundays or the grilled cheese sandwich you’ve been perfecting for twenty years. The same principles apply. Use the best ingredients you can and keep at it. Don’t quit. You learn things when you burn things.

When it’s perfect or close to it, recognize why, remember what you did, and repeat again and again until your children ask you to teach them to make it.

This is not the last book or the “final word” on pizza, pasta, or anything else, but I hope you will find something in it of worth.

Love,

Chris

My brother, Marco; my grandfather Leonard “Big Sonny” Bianco; and me.

PIZZA (#ulink_fe3e4919-f208-5901-979e-27891750db82)

LOVE & MASTERS

Understanding and appropriating these two words has been a ghost in my machine for as long as I can remember. Take the word “master”: as far as I’m concerned we could do ourselves much good by just removing it from our vocabulary. The terms “pizza master,” “bread master,” or “whatever master” create a submissive or unequal relationship when they’re applied to food and all that makes coming to the table possible. When I am kneading or shaping dough, I rely solely on being present and responding to how much something needs, whether it’s just time or manipulation—I knead you and I need you. If someone asked me what business I was in, I’d say the relationship business—understanding the importance of relationships and my role in them applies to food, people, furniture, you name it. I want us both to be happy.

As for love, that’s a bit broader. I see love only as a four-letter word that does its best to explain what in most cases is unexplainable—we love our dogs, cats, friends, wives, husbands, family, God, and, yes, pizza. It’s taken my whole life thus far to get them in order and serve them appropriately. If I do all my most diligent foraging and preparation but am negligent on oven temperature or vessel or lack of a plate to put the food on, my intention will be at risk. Back in the late ’80s when wood ovens weren’t so popular, some people would watch me work and say, “The wood-fired oven—that’s the secret.” The secret that is no secret is even in the most Ferrari of ovens, shit in will be shit out, yet the most humble oven at the proper temperature with all aspects in balance and restrained harmony, will set you free.

PIZZA DOUGH (#ulink_7b1aa96d-114c-51d6-bb4d-46ff9c62f138)

This dough contains just four ingredients: water, flour, yeast, and salt. Let’s consider each one in turn. Before you make the dough for the first time, I want you to pour yourself a glass of the water you’ll be using and drink it. I want you to really taste it. It is going to rehydrate the flour, and its warmth will bring the yeast back to life. Ask yourself how salty it is, how sweet it is. Record your observations.

Next, think about the flour. What kind are you going to use? I like one that is high in protein (13 to 14 pcl, organic, and grown and freshly milled as close to home as possible), because it gives the finished crust a good chew. If you’re lucky enough to have a mill near where you live, pay a visit and ask about its flour and grain varietal. The flour is the biggest single factor in the flavor of your dough, so it’s something that you don’t want to compromise on.

Now the yeast. Yeast is life. Yeast is what makes bread different from everything else we eat. Here, for ease, I use active dry yeast. As you experiment, you may want to try fresh yeast, but active dry yeast will give you a good and consistent result.

And last, salt. Salt is flavor. It’s rare to see someone muck up a bread with too much salt. If anything, I find a lot of bread is insipid because it lacks salt. Pick a fine, not coarse, salt you like, preferably sea salt that has been minimally processed.

Makes enough for four 10-inch pizzas

1 envelope (2¼ teaspoons; 9 grams) active dry yeast

1 cups warm water (105° to 110°F)

5 to 5½ cups bread or other high-protein flour, preferably organic and freshly milled, plus more for dusting

2 teaspoons (12 grams) fine sea salt

Extra virgin olive oil, for greasing the bowl

Combine the yeast and warm water in a large bowl. Give the yeast a stir to help dissolve it, and let it do its thing for 5 minutes. You’re giving it a little bit of a kick-start, giving it some room to activate, to breathe.

When the yeast has dissolved, stir in 3 cups of the flour, mixing gently until smooth. You’re letting the flour marry the yeast. Slowly add 2 cups more flour, working it in gently. You should be able to smell the yeast working—that happy yeasty smell. Add the salt. (If you add the salt earlier, it could inhibit the yeast’s growth.) If necessary, add up to ½ cup more flour 1 tablespoon at a time, stirring until the dough comes away from the bowl but is still sticky.

Turn the dough out onto a floured work surface and get to work. Slap the dough onto the counter, pulling it toward you with one hand while pushing it away with the other, stretching it and folding it back on itself. Repeat the process until the dough is noticeably easier to handle, 10 to 15 times, then knead until it’s smooth and stretchy, soft, and still a little tacky. This should take about 10 minutes, but here, feel is everything. (One of the most invaluable tools I have in my kitchen is a plastic dough scraper. It costs next to nothing, and it allows me to make sure that no piece of dough is left behind.)

Shape the dough into a ball and put it in a lightly greased big bowl. Roll the dough around to coat it with oil, then cover the bowl with plastic wrap and let the dough rest in a warm place until it doubles in size, 3 to 5 hours. When you press the fully proofed dough with your finger, the indentation should remain.

Turn the proofed dough out onto a floured work surface and cut it into 4 pieces. Roll the pieces into balls and dust them with flour. Cover with plastic wrap and let them rest for another hour, or until they have doubled in size.

The dough is ready to be shaped, topped, and baked. If you don’t want to make 4 pizzas at a time, the dough balls can be wrapped well and refrigerated for up 8 hours or frozen for up to 3 weeks; thaw in the refrigerator and let come to room temperature before proceeding.

SHAPING PIZZA DOUGH

Hold the top edge of a piece of dough with both hands, allowing the bottom edge to touch the work surface, and carefully move your hands around the edges to form a circle of dough. You have to find your own style, but I usually just cup my hand into a C shape, turn my hand knuckle side up, and drape the dough off it, allowing gravity to do its work, so it gently falls onto the floured table. Imagine you’re turning a wheel. Hold that dough aloft, allowing its weight to stretch it into a rough 10-inch circle. Don’t put any pressure on it by pulling or stretching it, just let gravity do the job—you want that aeration and cragginess. Keep it moving, and it will start to relax—like we relax when we are on a sofa.

At this point, you’re ready to make a pizza. Lay the dough on a lightly floured pizza peel or inverted baking sheet. Gently press out the edges with your fingers. You will start to see some puffiness or bubbles now. Jerk the peel to make sure the dough is not sticking. If it is, lift the dough and dust the underside with a little flour (or, if no one is looking, blow under it very gently). Tuck and shape it until it’s a happy circle.

Top the pizza as per the instructions in any of the recipes that follow.

PROOFING DOUGH

In our Pizza Dough recipe, you proof the dough for up to 2½ hours, then divide it into balls and let it proof for another hour before you bake it. It tastes good. No problems. But what happens if you proof it for 7 hours? What if you let it go for 24 hours? Or 36? Or 48? It will be different, and that difference might be more to your taste than the basic dough. At 3 to 5 hours for the first proof, you will have a dough that will brown more quickly than a dough that’s proofed for 14 hours, because the yeast will not have converted as many of the sugars. The longer the dough proofs, and the more sugars are converted, the more it will have that smell of fermentation, and the more the sour flavors will develop. Many people (including me) love those flavors—like in a good sourdough bread—but here I don’t necessarily want too many of them, because I don’t want them to dominate the flavors of the pizza toppings. That said, there is no wrong way to go here. Make the dough a few times, following the recipe, until you feel comfortable. Then start to play with it. Determine how long a proof you like.

Bear in mind that where you are in the world will also play its part. If you’re making the dough in Iceland, it’s going to be different from making it in Phoenix. The climate is different, so it may need to proof for a little longer than 3 to 5 hours to start. Your water will be different, and it will affect the flavor of your dough. Never forget, we’re dealing with only four ingredients, and each one brings its own flavors and qualities to the pizza. So record the process as you go. Work with your sense of taste and your broader sensibility of the things you like. This basic dough recipe is only an early survey of a journey you get to finish yourself. The possibilities are endless.

CRUSHED TOMATO SAUCE (#ulink_8fefd8c4-0fc4-548c-8de2-5ba91e09faaa)

This is the sauce we use the most at our restaurants. It couldn’t be simpler. People are often surprised when they find out the sauce is uncooked, but canning tomatoes partially cooks them, and the heat of the oven finishes the process. The next question we usually get is why we don’t use fresh tomatoes, especially when our restaurants focus on seasonal ingredients. But fresh tomatoes are not always the best choice for sauce. The window for perfect ripe tomatoes isn’t very long, and in winter, pallid grocery store tomatoes are going to give you a real bummer of a sauce. One of the many beauties of pizza is that it relies on ingredients you can always have on hand. You just need a well-stocked pantry.

Beautifully canned or jarred tomatoes, preferably organic and delicious, are a celebration of height-of-season produce, a moment captured in time and available to you long after summer has gone. My partner, Rob DiNapoli, and I have our own Bianco DiNapoli brand canned tomatoes that we use at our restaurants. The tomatoes are organic and harvested in peak season and packed within hours. They’re steam-peeled and then canned in tomato juice (about 3 ounces of juice per 28-ounce can).

We don’t add any stabilizers, but we do add a bit of sea salt, because we found that adding a pinch of salt at canning resulted in more depth of flavor. So, because our canned tomatoes contain a scant amount of salt, we don’t add salt when making this sauce. Be alert to the salt content of whatever canned tomatoes you use. Don’t just read the label—taste them before using them. Cooking will reduce the sauce and the saltiness will become more pronounced, so you want to be on the lighter side of salinity when you set out—on the road to perfection instead of already at the destination.

We also include four fresh basil leaves in every can. When you macerate the tomatoes as you make the sauce, you’ll infuse them with the basil. Not all canned tomatoes include basil. This recipe calls for adding fresh basil to the sauce. If your tomatoes already include the herb, taste them and see if you want to take it a step further or if you’re happy with them as is. We always add a few hand-bruised fresh leaves too.

Makes enough for four 10-inch pizzas

One 28-ounce can whole tomatoes

1 generous tablespoon extra virgin olive oil

4 or 5 fresh basil leaves, torn and bruised (optional if the canned tomatoes include basil; see headnote)

Fine sea salt (optional)

Empty the can of tomatoes, with their juice, into a large bowl. Add the olive oil with the basil and salt (if using) and using your hands, crush the tomatoes; discard any bits of skin or hard yellow “shoulders,” or cores. The better the tomato, the less likely you are to find shoulders and hard cores. You want to end up with a textured yet silky sauce. I like it when the sauce isn’t uniform, when there are still bits and pieces of tomato; I also don’t like using an immersion blender or food processor because these can bring out the bitterness of the seeds. A hand-crushed sauce has a better mouthfeel and won’t be so one-dimensional.

Time is the invisible ingredient here, so if you can, let the sauce sit for about an hour so the flavors can marry. Of course, in our restaurants, we don’t always have the luxury of that time, and the sauce is still great.

PIZZA MARGHERITA (#ulink_3350ff37-f563-5d94-9d4a-5cba3098374f)

Almost everyone knows a Margherita pizza, or at least a cheese pizza. For me, that widespread familiarity was an opportunity to exceed people’s expectations, to check off the requisite boxes but go above and beyond with optimal ingredients. The Margherita is the quintessential Neapolitan pizza—hell, let’s just say it is the quintessential pizza. Its much-debated origin is as much a tale of national identity as it is of pizza. The story goes that back in 1889, just twenty-eight years after Italy had been unified as a country. Queen Margherita of Savoy and her king, Umberto I, were touring the nation to encourage a sense of nationalism. In the south especially, people were still angry about the loss of their independence; they weren’t easy days. So it seems especially powerful that it was in Naples, stronghold of southern Italy, that the most emblematic style of the arguably most emblematic dish of Italy was born. Legend has it that Margherita had noticed people across the country eating pizza, and she wanted to try it. Whether she was just curious or was trying to align herself with the common people, we can’t know, but I love the idea of a queen drawing closer to her subjects through food. Neapolitan chef Raffaele Esposito presented her with a tomato, mozzarella, and basil pizza—the red, white, and green mirroring the colors of the new Italian flag—and named the pizza in her honor. To me, the beauty of this story is that it embodies my motivating belief that food is about so much more than physical sustenance or pleasure. It’s about identity and place and relationships—and how the best food happens when we begin with an intention and work from a place of attention, just as Raffaele did for his queen.

The Margherita is perfect as is, but it’s also a perfect canvas for other ingredients. Just remember that when you add or remove something from a pizza, you need to accommodate for that gain or loss, be it a matter of texture, moisture, flavor, or the like. For example, adding ricotta cheese could make your pizza more watery, so you’d want to use a little less tomato sauce to balance things out.

Makes one 10-inch pizza

One ball Pizza Dough (#ulink_3433f2de-175e-5a31-a2f7-2cf44c21ab42), rested and ready to shape

2 ounces fresh mozzarella, torn into cubes

6 tablespoons Crushed Tomato Sauce (#ulink_b5865456-7e91-5474-be97-c3f47109b61a), with an added glug of extra virgin olive oil

A pinch or two of finely grated Parmigiano-Reggiano (optional)

Fine sea salt (optional)

Extra virgin olive oil, for drizzling

5 fresh basil leaves

Position a rack in the lower third of the oven (remove the rack above it) and place a pizza stone on it. Turn up your oven to its maximum setting, as high as it will go, and let that baby preheat for a solid hour. Don’t even bother putting together your pizza until the oven’s been going for an hour.

Once the oven is preheated, grab a pizza peel and give it a nice, light dusting of flour. This will help prevent the pizza from sticking when you slide it from peel to stone. (If you don’t have a peel, you can use a cookie sheet or an inverted baking sheet.)

Shape the dough (#ulink_682689d9-beac-5c7a-a2e6-ee6a4ca7faa1) as directed and set the prepared dough on the peel. Jerk the peel to make sure it’s not sticking. If it is, lift the dough and dust the underside with extra flour (or, if no one is looking, blow under it very gently). Tuck and shape it until it’s a happy circle.

Taste your mozzarella and your tomato sauce to see how salty they both are and make a mental note of this. Spoon the tomato sauce evenly over the pizza, using the back of the spoon to spread the sauce, starting from the center and stopping about ¾ inch—a fat thumb’s width—from the edges. (With a hand-crushed tomato sauce, the consistency of the sauce over the pizza’s surface will be uneven. It’s inevitable.) Sprinkle the Parmigiano, if using, over the sauce. Let the spots where the tomato sauce is thinner guide you as to the placement of the mozzarella—hit those drier spots with a bit more mozzarella. If when you tasted your sauce and cheese earlier you determined that the salinity wasn’t quite there yet, sprinkle the pizza with some salt. Then give it a very light drizzle of olive oil.

Open the oven and, tilting the peel just slightly, give it a quick shimmy-shake to slide the pizza onto the pizza stone. Bake the pizza for 10 to 15 minutes, until the crust is crisp and golden brown.

Remove the pizza with the peel and immediately add the basil leaves, laying them evenly across the top. The heat of the pizza will wilt the leaves slightly and release their heady fragrance. Enjoy immediately!

Note: This recipe is more detailed than the pizza recipes that follow—you can think of it as a master recipe for assembling and baking pizza.

BEFORE OR AFTER

Most traditional recipes call for basil to be cooked with the pizza, which is totally fine. I prefer tearing and rough-handling fresh basil leaves over the cooked pizza and letting the heat release the aroma. The essential oils from the basil provide a pleasing texture and flavor profile.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: