Полная версия:

Portrait of an Unknown Woman

VANORA BENNETT

Portrait of an Unknown Woman

To Chris, with love

Many more people than the writer find themselves working on an unfinished book. I am enormously grateful both to Susan Watt and her team at HarperCollins for their wonderful editing, guidance and even a desk to finish the writing, and to my delightful agent Tif Loehnis and all her colleagues at Janklow & Nesbit. I’m no less indebted to my family. My sons Luke and Joe have been extraordinarily patient while I shut myself away to finish my chapters. Their nanny Kari has kept the house going while my parents offered all sorts of moral support. My father-in-law George has turned out to be a superb marketing manager. And I owe more thanks than I can find words for to my husband Chris for all the brilliant story ideas he came up with while reading many early drafts and chapters in whatever spare multi-tasking minutes he could make between legal cases. Most of all, though, I’d like to express my gratitude to Jack Leslau, whose lifetime’s work – the development of a fascinating theory about John Clement’s true identity, based on his study of Holbein’s paintings – was the starting-point for this book.

CONTENTS

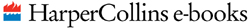

Plan for first portrait of the More family PART ONE Portrait of Sir Thomas More’s Family PART TWO Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling PART THREE Noli-Me-Tangere PART FOUR After the Ambassadors Author’s note BibliographyPlan for FIRST PORTRAIT OF THE MORE FAMILY by Hans Holbein the Younger, painted at Chelsea in 1527-28, destroyed by fire in the 18th century.

PART ONE

1

The house was turned upside down and inside out on the day the painter was to arrive. It was obvious to the meanest intelligence that everyone was in a high state of excitement about the picture the German was to make of us. If anyone had asked me, I would have said vanity comes in strange guises. But no one did. We weren’t admitting to being so worldly. We were a Godly household, and we never forgot our virtuous modesty.

The excuse for all the bustle was that it was the first day of spring – or at least the first January day with a hint of warmth in the air – a chance to scrub and shake and plump and scrape at every surface, visible and invisible, in a mansion that was only a year old anyway, had cost a king’s fortune in the first place, and scarcely needed any more primping and preening now to look good in the sunshine. From dawn onwards, there were village girls polishing every scrap of wood in the great hall until the table on the dais and the panels on the walls and the wooden screens by the door alike glistened with beeswax. More girls upstairs were turning over feather pillows and patting quilts and brushing off tapestries and letting in fresh air and strewing pomanders and lavender in chests.

The hay was changed in the privies. The fireplaces were scraped clean and laid with aromatic apple logs. By the time we came back from Matins, with the sun still not high in the sky, there were already clankings and chop-pings from the kitchen, the squawked death agony of birds, and the smell of energetically boiling savouries. We daughters (all, not necessarily by coincidence, in our beribboned, embroidered spring best) were put to work ourselves dusting off the lutes and viols on the shelf and arranging music. And outside, where Dame Alice kept finding herself on her majestic if slightly fretful tour of her troops (casting a watchful eye down the river to check what boats might be heading towards our stairs), there was what seemed to be Chelsea’s entire supply of young boys, enthusiastically pruning back the mulberry tree that had been Father’s first flourish as a landowner – its Latin name, Morus, is what he called himself in Latin too (and he was self-deprecating enough to think it funny that it also meant ‘the fool’). Others were shaping the innocent rosemary bushes, or tying back the trees espaliered around the orchard walls like skinny prisoners; their pears and apples and apricots and plums, the fruits of our future summer happiness, still just buds and swellings, vulnerable to a late frost as they took tomorrow’s shape.

It was the garden that kept drawing everyone out, and the river beyond the gate. Not our stretch of wild water, which the locals said danced to the sound of drowned fiddles and which was notoriously hard to navigate and moor from. Not the little boats that villagers used to go after salmon and carp and perch. Not the view of the gentle far shore, where the Surrey woods with their wild duck and waterfowl stretched back to the hills of Clapham and Sydenham. But the ribbon of river you could see from Father’s favourite part of the garden, the raised area which gave the best possible view of London – the rooftops and the smoke and the church spires – which used to be our home until we got quite so rich and powerful, and which he, almost as much as I, couldn’t bear to pass a day without seeing.

First Margaret and Will Roper came out, arm in arm, decorous, stately, married, learned, modest, handsome and happy, seeming to me, on that scratchy morning, unbearably smug. Margaret, the oldest of the More children and my adopted sister, was twenty-two like her husband, a bit more than a year younger than me; but they were already so long settled in their shared happiness that they’d forgotten what it was to be alone. Then Cecily with her new husband, Giles Heron, and Elizabeth with hers, William Dauncey, all four younger than me, Elizabeth only eighteen, and all smirking with the secret pleasure of newlyweds, not to mention the more obvious pleasure of those who had had the good fortune to make advantageous marriages to their childhood sweethearts and find their new husbands’ careers being advanced by regular trips to court and introductions to the great and good. Then Grandfather, old Sir John More, puffed up and dignified in a fur-trimmed cape (he’d reached the age where he worried about chills in the spring air). And young John, the youngest of the four More children, shivering in his undershirt, so busy peering upriver that he started absentmindedly pulling leaves off a rose bush and scrunching them into tiny folds until Dame Alice materialised next to him, scolded him roundly for being destructive, and sent him off to wrap up more warmly against the river breezes. Then Anne Cresacre, another ward like me, managing, in her irritating way, to look artlessly pretty as she arranged her fifteen-year-old self and a piece of embroidery near John. In my view there was no need for all the draping of her long limbs and soft humming in her tuneful voice and that gentle smiling with her lovely little face that she did whenever John was around. It was obvious. With all the money and estates she’d been left by her parents, Father would have John marry her the day she came of age. What would be the point of bringing up a rich ward otherwise? Of all his wards, it was only me he seemed to have forgotten to marry off, but then I was several years too old to marry his only son.) Anne Cresacre didn’t need to try half so hard. Especially since you could see from the doggy way John looked at her that, even if he wasn’t very clever, he knew enough to know that he’d been in love with her all his life.

The sun came out on young John’s face as he came back, better dressed now for the gusty weather, and he screwed up his eyes painfully against the harshness of the light. And suddenly the peevish ill-temper that had been with me through a winter of other people’s celebrations – a joint bride-ale for Cecily and Elizabeth and their husbands, followed by Christmas celebrations for our whole newly extended family – seemed to pass, and I felt a pang of sympathy for the newly man-height boy. ‘Have you got your headache again?’ I asked him in a whisper. He nodded, trying like me not to draw anyone’s attention to my question. His head ached all the time; his eyes weren’t strong enough for the studying that made up so much of our time, and he was always anxious that he wasn’t going to perform well enough to please Father or impress pretty Anne, which only made it worse. I put a hand through his skinny arm and drew him away down the path to where we’d planted the vervain the previous spring. We both knew it helped with his headaches, but the clump that had survived was still woody and wintry. ‘There’s some dried stuff in the pantry,’ I whispered. ‘I’ll make you a garland when we get back to the house, and you can lie down with it for a while after dinner.’ He didn’t say anything, but I could sense his gratitude from the way he squeezed my hand against his bony ribs.

One moment of kindness reassured him; and it was enough to add honey to my view of everything too. When Dame Alice came back from her own spontaneous little stroll in the garden, rejoining the crowd gathered as if by chance and staring towards the spire of St Paul’s, I was touched to see our stepmother – Father’s second wife, who’d married him just before I’d come to the house, and looked after his four children and the wards he’d taken on, as sensibly and lovingly as if they’d been her own – had been quietly taking trouble with her hair. She always laughed robustly but she didn’t like it when Father teased her about the size of her nose. Her great beauty was her beautiful broad forehead, and now she’d brushed her hair – with its stray streaks of grey blackened with the elderberry potion she liked me to make for her – back off it to show the unlined, luminous skin at its best.

Father’s teasing could be cruel. Even Anne Cresacre, who had nerves of steel, wept with frustration over the box he gave her for her fifteenth birthday. She thought it would contain the pearl necklace she’d been asking for for so long. But it turned out there was nothing in it but a string of peas. ‘We must not look to go to Heaven at our pleasure or on feather beds,’ was his only comment, along with that quizzical, birdlike look from far away that reminded you he wore a hair shirt under his robes and wouldn’t drink anything but water. At least she had enough presence of mind to overcome her disappointment and say to him at dinner, as prettily as ever, ‘That is so good a lesson that I’ll never forget it,’ and win one of those sudden golden smiles of his that always made you forget your fury and be ready to do anything for him again. So that time it came out all right, and anyway Anne Cresacre could look after herself. But I thought he should be kinder to his own wife.

Dame Alice could do what she liked to her hair on this day, anyway. Father was the only one who wasn’t here. He was away somewhere, like he always was since we’d moved to Chelsea. Court affairs; the King’s business. I lost count of what and where. Even when he reappeared, looking tired, with the new gold spurs that he didn’t really know what to do with clinking uselessly against a horse’s muddy sides, and we all rushed out to see him, he just shut himself away in the private place he’d built in the garden – his New Building, his monk’s cell – and prayed, and scourged himself, and fasted. We hardly knew him any more. But I had heard him promise Dame Alice when he last set off that he’d be back as soon as the painter arrived. And I happened to see that morning that she’d laid out some of his grandest clothes – the glistening fur-lined black cape, the doublet with the long, gathered sleeves of lustrous velvet attached that were long enough to hide the hands whose coarseness secretly embarrassed him. He liked to believe he just wanted his portrait painted to return likenesses of himself to his learned friends in Europe, who were always sending him their pictures. But being painted in those clothes spoke of something more. Even in him, worldly vanity couldn’t quite be extinguished.

And so our eyes devoured the river. I could almost feel the pull of everyone’s waiting and wishing. Longing to display ourselves to Hans Holbein, the young man sent to us from Basel by Erasmus – a living token of the old scholar’s continuing affection for us, long after he stopped living with us and went back to his books abroad – in memory of the good old days when Father’s friends were men of the mind, instead of the spare-faced bishops whose company he’d come to prefer these days. In those times ideas were still games, and the worst argument you could imagine was Father’s with Erasmus over what he should call the book he was writing about an imaginary nowhere land (which had ended up being as much of a best-seller as any of Erasmus’ works). We were longing to show ourselves as the accomplished, educated graduates of an experimental family school that Erasmus had always, in his almost embarrassingly flattering and charming way, praised to the heavens all around Europe as Plato’s Academy in its modern image. And longing to be back, at least on canvas, in a time when we were all together.

Except me. Even if I was staring upriver as longingly as anyone else, I certainly wasn’t looking for any German craftsman bobbing up and down in the distance with a pile of travel-stained boxes and bags bouncing around next to him. He’d be along soon enough. Why wouldn’t he, after all, with his way to make in the world, a recommendation in his pocket, and the chance to make his reputation by painting our famous faces? No, I was waiting for someone else. And even if it was a secret, childish kind of waiting – even though I had no real reason to believe my dream was about to come true and the face I so wanted to see was truly about to appear before me – it didn’t lessen the intensity with which I found myself staring at each passing boat. I was looking for my teacher from the past. My hope for the future. The man I’ve always loved.

John Clement came to live with us when I was nine, not long after my parents died and I was sent from Norfolk to be brought up in Thomas More’s family in London. John Clement had been teaching Latin and Greek at the school that Father’s friend John Colet had set up in St Paul’s churchyard, and Father and Erasmus and all the other friends of those days – Linacre and Grocyn and the rest – had made their passion.

They were all enthusiasm and experiment back then, all Father’s learned friends. When the new king was crowned, and the streets of London were hung with cloth of gold for the coronation – a sure sign that there’d be no more of the old King Henry’s meanness – they somehow got it into their heads that a new golden age was beginning in which everyone would speak Greek and study astronomy and cleanse the Church of its mediaeval filth and laugh all day long and live happily ever after. Erasmus once told me that the letter his patron Lord Mountjoy sent him, telling him to come to England at once and sending him five pounds for his travel expenses, was half-crazy with happiness and hope about the new King Henry. ‘The heavens laugh; the earth rejoices; all is milk and honey,’ it said.

It would surely have curdled all that milk and honey they were swimming in back then if only they’d known how quickly everything would go wrong. That within ten years their playful shared mockery of the bad old ways the old Church had got into would have turned into the deadly battle over religion that we were living through now. That one of Erasmus’ European disciples, Brother Martin of Wittenberg, would have pushed their notion of religious reform so far that peasants all over the German lands had started burning churches and denouncing the Pope and declaring war on both their spiritual and temporal rulers. That Father would have responded by giving up his belief in reforming Church corruption, taken court office instead, got rich, and been transformed into the fiercest defender of the Catholic faith against the radical new reformers he now called heretics – an about-face so dramatic that we didn’t dare discuss or even mention it. That Erasmus, the only one to preserve the memory of those hopes that we’d all entered a more civilised age of debate and tolerance when the new king came to the throne, would leave our house and go back to Europe, from where he’d spend his old age wearily mocking his greatest English friend for becoming a ‘total courtier’ and wondering at the evil real-life form his gentle dreams had taken.

But even back then, the happy humanist throng couldn’t just sit around all day laughing at the wonder of being alive in their land of milk and honey. They had to do something to mark the start of the golden age. First there was the school at St Paul’s. And then, when Father realised how many children he’d gathered in his own house, his four and the orphans like me and Giles and Anne, he persuaded Dean Colet to let him hire away a teacher from the school and set up his own personal humanist academy.

John Clement’s chambers were up at the top of the old-fashioned stone house we were brought up in in London, which had so many creaking wooden floors and dark little corridors and hidden chambers that it could easily have been a ship, so it was natural and pleasing that its name was the Old Barge. He lived at the other end of the corridor from our rooms, next to Erasmus and Andrew Ammonius. If we were playing in the corridor, we had to tiptoe past the grown-up end, shuffling our toes through the rushes, so as not to disturb them while they were thinking.

John Clement was big and tall – a gentle giant with an eagle’s nose and long patrician features and a dark, saturnine aspect that could easily have lent itself to looking bad-tempered if he hadn’t always worn a weary, kind, rather noble look instead. He had black hair and pale blue eyes with the sky in them. He was Father’s age, though taller, with broad warrior shoulders. You could guess at his physical energy – he strode off down the paving stones of Walbrook or Bucklersbury on great impatient legs every afternoon, instead of sleeping after dinner, and he taught us our Latin and Greek letters by pinning them to the archery target in the garden and letting us shoot them through with arrows. We were city children, being raised in a mercantile elite of burghers and aldermen who only kept bows and arrows gathering dust on a hook because they were obliged to by law, and would never raise a sword, so that was our only experience of the aristocratic arts of war. We loved it. Dame Alice raised her eyebrows at John Clement’s preference but Father just laughed. ‘Let them try everything, wife,’ he said. ‘Why ever not?’

Despite his long, athletic body with its muscles and quick reflexes, there was nothing in John Clement that signalled any wish to fight. He had a natural authority that commanded our respect, but he was also very patient with us children, and always ready to listen to other people and draw stories out of them; a comforting paternal presence. He wasn’t like the other adults we knew – the brilliant talkers and thinkers who came to Father’s table – because he was shy about talking of himself. He read a lot; he studied Greek in his room; but he was modest about sharing his thoughts with adults, and especially quiet and respectful around the great minds Father gathered around himself.

It was a different story when he was alone with us. He was so good at playing with words that we children hardly noticed we were also learning Latin and Greek, rhetoric and grammar. To us it was all a great game: verbal melodies and counterpoint in which every voice was always on the verge of laughing and one voice, his, was shaping the jokes.

Of all the games, the one he played best was history. Our serious rhetoric lessons – we studied rhetoric and grammar for several years before moving on to the higher arts of music and astronomy – were drawn from the history games we played together. So were our Latin translation lessons and our first attempts at Greek. He took snippets of street stories about the long-gone wars and embroidered them into tales of derring-do that made it easy for the youngest children in the group to enjoy themselves as much as Margaret and myself. We would put whatever had struck us most in our own lives into the story, then translate the latest bit of play-acting into Latin and back into English. One day, when I was still young and greedy and letting my mind wander to the strawberries ripening in the garden, I even put my gluttonous wish to eat them in. I made the wicked King Richard III pause before some villainous act and tell the Bishop of Ely: ‘My Lord, you have very good strawberries at your garden in Holborn. I require you to let us have a mess of them.’ It made everyone laugh. Father came into the classroom and helped us write the episode down exertationis gratia – for the sake of practice. One day, he said, he’d write a proper history of Richard III, and publish it, and it would be based on our games and the similar ones John had played with the boys at St Paul’s school when he was teaching there. And there was a dish of strawberries on our own table for dinner that day.

But it wasn’t all laughter and strawberries. There was always something sad about John Clement too: a sense of loss, a softness that I missed in the bright, brittle Mores.

He found me alone in my room one rainy Thursday, crying over the little box of things I’d brought with me from Norfolk. My father’s signet ring: I was remembering it on his little finger – a great sausage of a finger. And a prayer book that had belonged to my mother, whom I’d never seen, who died when I was born, but who my father had told me looked just like me – dark, and long-legged, and long-nosed, and creamy-skinned, with a serious demeanour but the hope of mischief always in her eyes. I didn’t remember much about my real father (except the official fact that he was a knight who left me just enough of a dowry to put me on the market for adoption by rich Londoners after his death). But I still felt the warmth of him. He was a bear-hugger with a red face and a shock of dark hair. And when he had you inside one of his embraces, half-stifled but happy, you knew he’d always keep you safe. In his arms, talking about the person we’d both lost, so gently and fondly that our yearning for her almost re-created her. She would be kneeling at her prayers, with the book in hand. (That was the only way I could imagine her – like she was in the effigy in the chapel – impossible to picture what it would have felt like for this perfect woman to have touched or talked to me.)

My father and I were united by this love. So nothing prepared me for them bringing him back from hunting one morning on the back of his horse. He’d broken his neck at a jump – a foolish sort of death. No one comforted me. You’re not really a child any more at nine. I dressed myself for his funeral, and dropped my own handful of soil on his coffin, and began several years of quiet life in corridors: watchful, eavesdropping on the lawyers and relatives as they made plans for me; picking things up, magpie fashion, storing away my few memories and what tokens of my parents I could before I was sent away to be watchful in other people’s corridors. My mother had known Thomas More long ago, in London, before her marriage. It was a whim on his part – a kindly whim – to take me. But he wanted me to think of him as my father from now on. He told me that, with a sweet look on his face, when I turned up at the Old Barge.