скачать книгу бесплатно

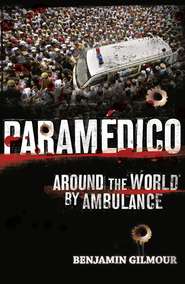

Paramédico

Benjamin Gilmour

Around the world by ambulance.Paramédico is a brilliant collection of adventures by Australian paramedic Benjamin Gilmour as he works and volunteers on ambulances around the world. From England to Mexico, and Iceland to Pakistan, Gilmour takes us on an extraordinary thrill-ride with his wild coworkers. Along the way he learns a few things, too, and shows us not only how precious life truly is, but how to passionately embrace it.

To the men, women and children working on ambulances around the world.

CONTENTS

COVER (#u50194e03-4df3-56da-b4aa-20568f8a29eb)

TITLE PAGE (#u28931fcb-8b44-5c9f-9a3e-86006f7eb664)

DEDICATION (#uca5b3bda-af55-509c-aecb-b666e0914606)

INTRODUCTION (#u2676c614-495e-5c17-9c1d-f66da8ad70cd)

OUTBACK AMBO – AUSTRALIA (#ud99971db-2085-58c7-9655-2ba0168ca4e3)

RUNNING WITH THE LEOPARD – SOUTH AFRICA (#ua0433f24-636f-5766-80a9-bb6886657cc7)

SHEIK, RATTLE AND ROLL – ENGLAND (#u06f620b6-4e17-5c99-b45b-ada2285b2fd8)

ALL QUIET! NEWS BULLETIN! – THE PHILIPPINES (#u9e869657-ff09-56c2-910c-320a1cce97d7)

DR AQUARIUS AND THE GYPSIES – MACEDONIA (#u2b2da4e4-0cb9-5277-a552-7b88131ba048)

ISLAND OF THE MONSTER WAVE – THAILAND (#litres_trial_promo)

A COUNTRY TO SAVE – PAKISTAN (#litres_trial_promo)

THE NAKED PARAMEDIC – ICELAND (#litres_trial_promo)

DEATH IN VENICE – ITALY (#litres_trial_promo)

A HULA SAVED MY LIFE – HAWAII (#litres_trial_promo)

THE CROSS OF FIRE – MEXICO (#litres_trial_promo)

AUTHOR NOTE (#litres_trial_promo)

GLOSSARY (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

BY THE SAME AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

COPYRIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION

From the day of its invention the ambulance has attracted a magnetic curiosity from humans around the world. This vehicle racing to the scene of accidents and illness demands attention. When you hear one coming, you turn. When you watch it pass you wonder, if only for a moment, where it might be going, who is inside and what horrific mishap the patient has suffered. After fifteen years spent in the back of ambulances I’ve come to realise that medics and paramedics are endlessly fascinating to the public.

But despite our appeal, the truth about us is largely hidden from view. It is hidden because, in the instant we drive past we have carried our secrets away, leaving nothing more than the wail of a siren. We are hidden because the usual depiction of paramedics on film and television is mostly a fantasy. The title of hero is forced upon us, and what is lost is who we really are.

Right now, as you read this, more than a hundred thousand ambulance medics in all manner of unusual and remote locations across the planet are responding to emergencies. They are scrambling under crashed cars, carrying the sick down flights of stairs, scooping up body parts after bombings, comforting the depressed, resuscitating near-dead husbands at the feet of hysterical wives, and stemming the blood-flow of gunshot victims in seedy back alleys. A good number too are just as likely to be raising an eyebrow at some ridiculous, trivial complaint their patient has considered life-threatening. Each of these medics could fill a book just like this one, with adventures many more extreme, dangerous and shocking than those recounted here.

My fascination with the lives of people from countries and cultures other than my own is driven by my ultimate desire to understand humanity. And so I travel at every opportunity to observe how people interact, and learn why they believe what they do, how they live and how they die and how they grieve. From the age of nineteen, during periods of leave each year, I have worked or volunteered with foreign ambulance services. Whether acting as a guest or consultant, I stayed sometimes for a month, other times more than a year. Every day it has been a privilege. There are few professions like that of an ambulance worker – we have a rare licence to enter the homes of complete strangers and bear witness to their most personal moments of crisis.

Globally, the make-up of ambulance crews is varied, though it’s generally agreed there are two models of pre-hospital care delivery – the Anglo-American model based on one or two paramedics per ambulance, or the Franco-German model where the job is performed by doctors and nurses. Over recent years, a number of Anglo-American systems have also introduced paramedic practitioners with skills that, until now, have been the strict domain of emergency physicians. Pre-hospital worker profiles also include drivers and untrained attendants who can still be found responding in basic transport ambulances across many developing countries. Since cases demanding advanced medical intervention represent only a small percentage of emergency calls, it would be a mistake to judge ambulance workers as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ solely on clinical ability. Consequently, I have chosen to explore the world of many ambulance workers, no matter where they are from or what their qualifications. It is true that ambulance medics are united by the unique challenges of their job. They are members of a giant family and they understand one another instantly. While the work may differ in its frequency, level of drama and cultural peculiarities, there is no doubt that medics the world over experience similar thrills and nightmares.

As a paramedic and traveller, I’ve enjoyed the company of my brothers and sisters in many exotic locations. I’ve lived with them, laughed with them and cried with them. And wherever it was I journeyed, my ambulance family not only showed me their way of life, they also unlocked for me the secret doors to their cities and the character of their people, convincing me that paramedics are the best travel guides one can hope to have.

More than a story about the sick and injured, Paramédico is about the places where I have worked and the people I have worked there with. It’s about the men and women who have remained a mystery to the world for long enough.

So, climb aboard, buckle up, and embark with me on these grand adventures by ambulance.

OUTBACK AMBO

Australia

For two weeks I have sat here in this fibro shack along the Newell Highway listening to the ceaseless drone of air-conditioning, waiting for the sick and injured to call me. Coursework for my paramedic degree is done and all my novels are read. Now I wait, occasionally wishing, with guilt, for some drama to occur, some crisis, no matter how small, anything to break the monotony of my posting.

From time to time my mother sends me a letter or her ginger cake wrapped in brown paper. For the second time today, I drive to the post office in my ambulance.

I’m stationed in Peak Hill in central New South Wales, a town some locals might consider their whole world. But to me, a nineteen-year-old city boy with an interest in surfing and clubbing, I am cast away, marooned, washed up in the stinking hot Australian outback.

‘Sorry, champ,’ says the post officer. ‘Nothing today.’

And so I drive my ambulance around the handful of quiet streets where nothing ever changes, where I rarely see a soul. Shutters are down, curtains drawn, doors shut. Where are they all, I wonder, these people who apparently know my every move?

I turn down towards the wheat silo and park, imagining how I would treat someone who had fallen from the top of it. After that I go to meet a flock of sheep with whom I’ve learnt to communicate. Much of it is non-verbal. We just stand there, the flock and I, face to face, staring quietly, contemplating what the other’s life must be like. Now and then we exchange simple sounds by way of call-and-response. Whenever I think I’ve gone mad I remind myself that most people talk freely to their pets without a second thought.

Earlier in the year, the Ambulance Service of New South Wales sent my whole class to remote corners of the state. I understood, of course, that in our vast country with its sparsely populated interior, everyone is equally entitled to pre-hospital care. Only problem is that few applications to the service are received from people living in the bush. Instead, young, degree-qualified city recruits from the eastern seaboard end up in one-horse towns.

As I entered the Club House Hotel in Caswell Street on my first night, twelve faces textured like the Harvey Ranges turned my way, looked me up and down taking in my stovepipe jeans, my combed hair and patterned shirt. As if my appearance was not out of place enough, I foolishly ordered a middy of Victoria Bitter and the room erupted in thigh-slapping laughter. Before I ran out, a walnut of a man nearest to me leant over to offer some local advice.

‘Out here, mate, it’s a schooner of Tooheys New, got it?’

I never went back to the pub, at least not socially. When called there in the ambulance for drunks fallen over, I was always greeted with the same row of men in the same position at the bar, like they had never gone home. It didn’t take me long to realise I’d need to find entertainment elsewhere.

In less than a month Kristy Wright, an actor playing the role of Chloe Richards on the evening soap Home & Away, has become the object of my affection. As the elderly will attest, a routine of the ordinary brings security of sorts, a familiar comfort, and Home & Away is just this for a lonely paramedic with too much time on his hands and not enough human company. Kristy is not particularly glamorous, nor is she Oscar material. Perhaps it’s her likeness to my first proper girlfriend, a ballerina who ran off to Queensland, married someone else, and broke my heart. Whatever the reason, I’m deeply smitten and make sure never to miss an episode.

For a small fee I have taken accommodation in the nurses’ quarters on the grounds of Peak Hill’s tiny brick hospital with its single emergency bed. Adjacent to the hospital lies the ambulance station consisting of a small office, a portable shed with air-conditioning and a garage containing an F100 and a Toyota 4x4 ambulance for difficult terrain. My new home next door is a freestanding weatherboard cottage, a little rundown but quaint nonetheless. Lodging at these nurses’ quarters initially sounded quite appealing to a young, single man, but the place never came with any nurses in it.

At 8 pm I ladle some lentil soup out of a giant pot I prepared earlier in the week, heating it up on the electric stove. After dinner, at 9 pm, I run the bath, making sure my blue fire-resistant jumpsuit is hanging by the door and my boots are standing to attention below, ready for the next job – if I ever live to see it, that is. Two slow weeks and I’m beginning to think they should close the ambulance station down before their assets rust away. The population plummeted a few years ago when Peak Hill’s gold mine hit the water table and ceased operations. Locals left behind would disagree, but maybe ambulance stations ought to come and go with the mines.

When the call finally comes it catches me off guard, just as I knew it would, cleaving me from a deep 4 am sleep.

‘Huh?’ I grunt into the phone. The dispatcher in the Dubbo control room 80 kilometres away sounds just as vague.

‘Okay, what we got here, let me see, ah, semi rollover on the Newell Highway six kilometres south of Peak Hill … well, that’s about all I have, mate … good luck with it.’

I hang up, slide out of bed in my jocks, splash my face at the bathroom sink, head to the door.

Keys, keys, ambulance keys. I teeter on the remains of sleep, trying to think of where I put the keys. When I throw my legs into the jumpsuit I’m relieved to hear them jingling in a pocket. My boots are on and I’m out.

The engine of the Ford springs to life, the V8 gives a mighty roar, a call to action. Adrenalin, like petrol charging through the lines, ignites me for the fight. I flick on the red flashing roof lights, the grill lights on the front, and then, as I skid onto the highway, I let the siren rip through the stillness. There’s not a car in sight, no one at all to warn of my approach, but this run is for the hell of it. I’m doing it because I can, because for two weeks I’ve been bored out of my brain and I’ll be damned if I won’t make the most of a genuine casualty call.

The Ford is a missile; eight cylinders of muscle thundering down the highway. In no time I cover the six kilometres, wishing the crash was further away for a longer drive. Last month it took me sixty minutes on the whistle travelling at speeds of 150 kilometres per hour to reach a child fallen off a horse at a remote property.

Up ahead a pair of stationary headlights in the middle of the road beam at me. They appear, at first, to be sitting higher than normal, but when I get closer I realise the semitrailer to which they belong has flipped upside down. It’s a most peculiar sight.

No one has motioned me to stop. In fact, there is no one about at all, not even Doug the policeman. Further down the road I spy another truck pulled up with its hazard lights on and assume this driver must have called the job in.

The motor of the upturned semi is still idling. It’s an eerie sound in the absence of any other. I decide that, for the purpose of making the scene safe and preventing an explosion, I ought to switch it off.

From what seems to have been the passenger side of the truck a steady stream of blood runs slowly to the shoulder of the road. The entire cabin of the semi is crushed and when I call out ‘Hello there!’ I don’t even get a grunt of acknowledgement.

This is my job, I remind myself. It falls on no one else. It is precisely my duty, without further delay, to climb underneath the overturned truck, attempt to turn off the ignition and ascertain the number and condition of its occupants.

With a small torch in hand, I get down on my chest and crawl into a narrow passage about a foot high with twisted metal and shattered glass all around, my head is turned on the side, oil and bitumen brush my cheek until I reach an opening in front of me. Here I’m able to lift my head up and take a look around. When I do this my heart jumps like a stung animal as I find myself face-to-face with the driver, his head pummelled into a mushy, shapeless mess, his mouth gaping wide and a single avulsed eye glaring at me. For the first time ever I am simply too startled to shriek or utter any sound whatsoever. Confined like this makes a rapid retreat difficult. Instead, I am frozen in horror, just as the driver’s face may have been in the moment before it was destroyed by his dashboard.

After a few seconds, when I regain a little composure, I reach up to the keys dangling in the ignition and turn off the engine. At the same time I see a photo of a woman and child, smiling at the camera, some birthday party. Perhaps it was the last image the man saw before exhaling his final breath.

Almost as slowly as I entered the cabin I extract myself and return to the ambulance, shaking ever so slightly, to give Dubbo control a report from the scene.

It takes Peak Hill’s SES Rescue Squad five hours to remove the driver’s body. Most of this is spent waiting for a crane to arrive from Parkes. I stand in the shadows clutching a white folded body bag, reluctant to join the rescue volunteers, all ex-miners and rough farmhands cursing and spitting and slapping each other on the back.

At the hospital, the nurse on duty has called in Peak Hill’s only doctor, a short Indian fellow, to sign the certificate. When I unzip the body bag and pull it back, all colour drains from the doctor’s face, his eyes roll into his head and he grips the wall to stop himself from passing out.

‘Doc may need to lie down for a while,’ I say to the nurse as she leaps forward to prevent him falling.

By the time I finish at the morgue the sun is high over the Harveys and I reverse the ambulance into the station, putting it to bed for another two weeks.

Most of Peak Hill’s indigenous population lives in what is still known as ‘the mission’, a handful of streets on the south side of town once run by missionaries. In comparison to many Aboriginal missions in the Australian outback, the houses are fairly tidy and the occupants give us little trouble. Except for Eddy and his extended family, that is. When things become too monotonous in Peak Hill one can always rely on Eddy to get pissed, flog his missus or end up unconscious in someone’s front yard. Empty port flagons line the hallway of his house, a house without a door and with every window smashed in. Half the floorboards have been torn up for firewood in the winter.

Jobs often come in spurts and on the day after the semi rollover I scoop Eddy onto the stretcher and cart him to the hospital for his weekly sobering-up. In straightforward cases like this I work alone, making sure to angle the rear-vision mirror onto the patient for visual observation. Occasionally, to be certain the victim doesn’t pass away unnoticed, I attach a cardiac monitor for its regular audible blipping. This way I can keep my eyes on the road ahead.

Longer journeys are a little trickier. For these I must evaluate a patient’s blood pressure every ten minutes or so by pulling over and climbing into the back. It is hardly ideal, but sometimes necessary when I’m unable to find a suitable or sober candidate to drive the ambulance for me. A strategy the service conceived many years ago was to recruit volunteer drivers from the community, people familiar with the names and location of distant cattle stations and remote dirt tracks.

Charlie, a hulk of a man with handlebar moustache and hearty belly laugh is the best on offer. Unfortunately his job as a long-haul coach driver means he’s rarely in town when I need him. Perhaps one day he will join the service full-time.

As for Lionel, Peak Hill’s only other volunteer officer, he is simply too crass to take anywhere at all. Unshaven, slouchy and barely able to complete the shortest string of words without adding expletives, Lionel is my last resort. Nonetheless, his job as the hospital caretaker means he torments me with racist, redneck tales and invitations to bi-monthly Ku Klux Klan gatherings held at secret locations in the Harvey Ranges. His open dislike of ‘boongs’ – a derogatory term for Aboriginal people – is another reason I don’t take him on jobs in the mission. Lionel’s most beloved pastime is ‘road kill popping’, which involves intentionally driving over bloated animals with his Ford Falcon in order to hear them ‘pop’ under the chassis. Worse still, less than a month after my arrival in Peak Hill, he snatched a snow-white cooing dove from the eaves of the ambulance station and ripped its head off, whining about the ‘pests’ inhabiting the hospital rafters. This callous act prompted me to slam the door in his face.

When my family drives up from Sydney to pay me a visit I take them to the Bogan River, just out of town. It’s a sorry little waterway but there are several picnic spots to choose from. In the shade of a snow gum we spread out a tartan blanket. My mum unwraps her tuna sandwiches and pours out the apple juice while my dad reflects on the subjects of solitude, meditation, Jesus in the desert. My sister and brothers are not normally so quiet and I sense everyone feels a bit sorry for me, as if I have some kind of incurable disease, all because I’m stuck here in Peak Hill.

Later that night, as no volunteer drivers are available, my dad offers to join me on a call to the main street. He’s still tying the laces of his Dunlop Volleys in the front seat when I pull up at the address. Above the newsagent, in a room devoid of any furniture, an eighteen-year-old male is hyperventilating and gripping his chest. The teenager is morbidly obese for his age, thanks to antidepressants and a diet of potato chips and energy drinks. What he is still doing in this town, estranged from his parents, roaming about jobless and alone, is beyond me.

‘My heart,’ he moans.

As I take a history and connect the cardiac monitor, I relish this rare moment. Doesn’t every son secretly dream of impressing his father with knowledge and skill? Our patient hardly requires expert emergency attention, but Dad observes my every move and his face is beaming.

Suspecting the patient has once again consumed too many Red Bulls, I offer him a trip to hospital and he nods. If I were him I too would rather spend my evening with the night-nurse than sit here alone. Once loaded up, I throw Dad the ambulance keys and give him a wink.

‘Wanna drive? Someone’s got to keep him company.’

For a second or two Dad stands there looking like a kid on Christmas morning.

No one visits me after that for the rest of my time in Peak Hill, but six months in I’m less concerned about isolation. Routines I’ve constructed help the time pass. I’ve also begun to feel the subtle tension that simmers below the surface of every country town, the whispering voices from unseen faces and the contradiction of personal privacy coupled with the compulsive curiosity to know the business of others. A lady in the grocery store last week was able to recite to me my every movement for three consecutive days: what time I left the station in the ambulance, where I drove to and what I did there. Sheep are dumb animals, she told me. My efforts to communicate with them at Jim Bolan’s property were futile and stupid. I was speechless. Never on any visit to my fleecy friends had I seen another human being. Perhaps the sheep themselves were dobbing me in? Back in Sydney, where people live side by side and on top of one another, a person can saunter about naked in the backyard and no one pays the least bit of notice. Those who imagine they will find some kind of seclusion in a country retreat should think again.

It’s August and my cases last month entailed an old man dead in his outhouse for at least a fortnight, a diabetic hypo to whom I administered Glucagon by subcutaneous injection and a motorcyclist with a broken femur on the road to Tullamore.

After browsing the internal vacancies around the state, I decide to apply for Hamilton in Newcastle. One of the controllers in Dubbo is a keen surfer like me and whenever he calls for a job we joke about starting a Western Division surfing team. I regret telling him about the Newcastle position because he immediately says he will go for it too, his length of service giving him a clear advantage.

As steady as I may be going in Peak Hill, the month ends with an accident that changes everything, an accident forcing me to leave town for my own safety.

At 10 pm on a Friday night I am in bed, lying awake in a silence one never hears in Sydney, imagining the wild time my friends are having there, bar-hopping around Darlinghurst and Surry Hills, seeing bands and DJs, laughing and flirting with girls.

When the phone rings, I jump back into the cold, dark room, sit bolt upright, snatching the receiver.

‘Peak Hill Station.’

‘Yeah mate, let’s see … some kid hit by a semi on the main street, says it’s near the service station. I’ll sort you out some back-up from Dubbo. They’re just finishing a transfer so it might be an hour or so, maybe forty-five – if they fang it. Booked 10.01, on it 10.02. Good luck.’

No matter how many truck drivers Doug the policeman books for speeding through the main street, few semitrailers slow down much. They have a tight schedule and Peak Hill is just another blink-and-you-miss-it town clinging to the highway.

As it turns out, the fourteen-year-old Aboriginal boy lying in the gutter has only been ‘clipped’ by the semitrailer, a hit-and-run, although I suspect the driver wouldn’t have noticed. A crowd from the mission has quickly formed and they urge me to hurry as I retrieve my gear.

‘C’mon brudda, ya gotta help tha poor fella, he ain’t in a good way mister medic.’

Relieved to find the boy conscious, I put him in a neck brace and begin a quick head-to-toe examination to ascertain his injuries. As I’m doing this I feel a hand squeeze my buttocks, more than one hand, in fact, until a good many are occupied with my bum cheeks. I look around but the crowd encircling me is too dense to identify a particular culprit. I wonder where Doug the policeman is, he always seems to arrive well after a drama is over.

The crowd shuffles back half a foot when I ask for some room, but pushes in again when I take a blood pressure reading. A second time I feel the hands, this time squeezing and caressing my buttocks with renewed enthusiasm, one of them even giving me an affectionate little slap. Such a thing is most distracting in emergency situations. Moreover, it’s shameless sexual harassment. I grab my portable radio, calling for urgent police assistance. That should wake Doug up, I think to myself. Again I demand the onlookers move away, but my request is ignored.

‘Listen brudda,’ says an elder among the group. ‘We don’t trust you whitefellas, we gotta watch you, make sure you do us a good job, you know wad I mean?’

Finally Doug turns up, huffing and puffing and waving at the crowd to move on. Reluctantly they do, now giving me space to load the patient. Doug offers to drive the ambulance to the hospital and I call off my back-up from Dubbo as the boy seems to have suffered little more than minor abrasions.

Early the next morning I am woken by the sound of a car with holes in the muffler going up and down the dirt road beside the nurses’ quarters. Crouching low, I crawl in my underwear to the kitchen where I’m able to peek out between the lace curtains on the window above the sink. Idling on the grass outside my place is a beaten-up, cream-coloured Datsun packed with Aboriginal girls.

‘Shit,’ I curse to myself. From my position at the window I can make out their conversation as they speculate on my whereabouts.

‘He ain’t come out from that house all morning, I reckon he in there, he in there, I’m telling ya.’

‘Maybe he gone walkabout.’