Полная версия:

In the Rose Garden of the Martyrs

CHRISTOPHER DE BELLAIGUE

In the Rose Gardenof the Martyrs

A Memoir of Iran

COPYRIGHT

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This edition published by HarperPress 2005

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2004

Copyright © Christopher de Bellaigue 2004

Sections of this book have appeared in Granta, the London Review of Books and the Paris Review

Christopher de Bellaigue asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

Extracts from the poetry of Rumi reprinted

by permission of Threshold Productions

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007113941

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2013 ISBN 9780007372812

Version: 2019-07-24

NOTE TO READERS

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

DEDICATION

Each day more than yesterday,

and less than tomorrow

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

NOTE TO READERS

DEDICATION

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

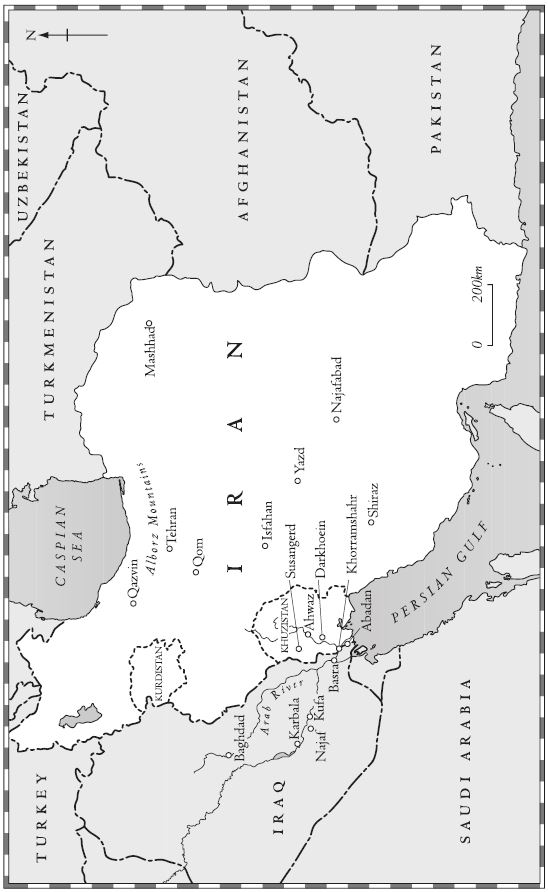

MAPS OF IRAN

1 Karbala

2 Isfahan

3 A Sacred Calling

4 Qom

5 Lovers

6 Reza Ingilisi

7 Gas

8 Parastu

9 Friends

10 Ashura

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

AUTHOR’S NOTE

PRAISE

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

Abdolrahman, Hassan: American convert to Islam who carried out an assassination on behalf of the Islamic Republic and then took refuge in Iran.

Alavi Tabar, Ali-Reza: Islamic revolutionary and holy warrior in the war against Iraq who later became an influential figure in Muhammad Khatami’s reform movement.

Amini, Reza: subordinate of the famous Isfahani commander Hossein Kharrazi.

Bani-Sadr, Abolhassan: the Islamic Republic’s first president, who later revolted against Ayatollah Khomeini and was forced into exile.

Bazargan, Mehdi: provisional prime minister after the Revolution, who resigned during the US hostage crisis.

Emami, Saeed: senior Intelligence Ministry figure of the 1990s, alleged mastermind of the ‘serial murders’ of dissidents.

Forouhar, Darioush: a minister after the Revolution, he fell out with the religious establishment and was one of the final victims of the ‘serial murders’.

Forouhar, Parastu: justice-seeking daughter of Darioush Forouhar.

Ganji, Akhar: investigative journalist, jailed for his part in exposing the ‘serial murders’ of dissidents in the 1990s.

Ghorbanifar, Manuchehr: arms dealer involved in the Iran – Contra scandal.

Hashemi, Mehdi: fanatical revolutionary whose rift with the establishment led to the exposure of the Iran – Contra scandal.

Hossein b. Ali: third Shia Imam, who was killed at Karbala in 680.

Khalkhali, Sadegh: revolutionary official, Iran’s ‘hanging judge’.

Khamenei, Ayatollah Ali: second president of the Islamic Republic and Khomeini’s successor as Supreme Leader, or Guide, of the Islamic Revolution.

Kharrazi, Hossein: inspirational Isfahani war commander.

Khatami, Muhammad: elected president in 1997, he failed to implement most of the democratizing reforms that he envisaged.

Khomeini, Ayatollah Ruhollah: father of the Islamic Revolution and the Islamic Republic’s first Supreme Leader, or Guide.

Makhmalbof, Mohsen: revolutionary film-maker.

Montazeri, Ayatollah Hossein-Ali: Khomeini’s designated successor, stripped of the succession for being too independent.

Muhammad Mossadegh: controversial prime minister who nationalized Iran’s oil industry and was deposed, in a CIA-run coup, in 1953.

Pahlavi, Muhammad-Reza: the final Shah of Iran, deposed in the 1979 Revolution.

Pahlavi, Reza: the founder of the Pahlavi dynasty, the Shah’s father.

Rafii, Muhammad-Ali: Isfahani cleric, subordinate of Hossein Kharrazi.

Rafsanjani, Ali-Akhar Hashemi: president between 1989 and 1997.

Rezai, Mohsen: Revolutionary Guards commander during the Iran – Iraq war.

Shirazi, Sayyad: army chief during the Iran-Iraq war.

Teyyeb, Haji-Rezai: Tehran mafioso.

Zarif, Sadegh: revolutionary, seminarian and, latterly, film-maker.

MAPS OF IRAN

CHAPTER ONE Karbala

Why, I wondered long ago, don’t the Iranians smile? Even before I first thought of visiting Iran, I remember seeing photographs of thousands of crying Iranians, men and women wearing black. In Iran, I read, laughing in a public place is considered coarse and improper. Later, when I took an oriental studies course at university, I learned that the Islamic Republic of Iran built much of its ideology on the public’s longing for a man who died more than thirteen hundred years ago. This is the Imam Hossein, the supreme martyr of Shi’a Islam and a man whose virtue and bravery provide a moral shelter for all. Now that I’m living in Tehran, witness to the interminable sorrow of Iranians for their Imam, I sense that I’m among a people that enjoys grief, relishes it. Iran mourns on a fragrant spring day, while watching a ladybird scale a blade of grass, while making love. This was the case fifty years ago, long before the setting up of the Islamic Republic, and will be the case fifty years hence, after it has gone.

The first time I observed the mourning ceremonies for the Imam Hossein, I was reminded of the Christian penitents of the Middle Ages, dragging crosses through the dust and bringing down whips across their backs. In modern Iran, too, there is self-flagellation and the lifting of heavy things – sometimes a massive timber tabernacle to represent Hossein’s bier – as an expression of religious fervour. The Christian penitents were self-serving; calamities such as the Black Death provoked a desire to atone, to save oneself and one’s loved ones from divine retribution. Iran’s grieving does not have this logic. This is no act of atonement, but a sentimental memorial. Iranians weep for Hossein with gratuitous intimacy. They luxuriate in regret – as if, by living a few extra years, the Imam might have enabled them to negotiate the morass of their own lives. They lick their lips, savour their misfortune.

I see Hossein alongside Tehran’s freeways, his name picked out in flowers that have been planted on sheer green verges. I see his picture on the walls of shops and petrol stations, printed on the black cloths that are pinned to the walls of streets. The conventional renderings show a superman with a broad, honest forehead and eyes that are springs of fortitude and compassion. A luxuriant beard attests to Hossein’s virility, but his skin is radiant like that of a Hindu goddess. He wears a fine helmet, with a green plume for Islam, and holds a lance. I once asked an elderly Iranian woman to describe Hossein’s calamitous death. She spoke as if she had been an eyewitness to it, effortlessly recalling every expression, every word, every doom-laden action. She listed the women and children in Hossein’s entourage as if they were members of her own family. She wept her way through half a dozen Kleenexes.

Every Iranian dreams of going to the town of Karbala, the arid shrine in central Iraq that was built at the place where Hossein was martyred. I went there myself, the camp follower of American invaders, and visited the Imam’s tomb. Inside a gold plated dome, Iraqis calmly circumambulated a sarcophagus whose silver panels had been worn down from the caress of lips and fingers. They muttered prayers, supplications, remonstrations. Suddenly, the peace was shattered by moans and the pounding of chests, splintered sounds of distress and emotion. Five or six distraught men had approached the sarcophagus. One of them was half collapsed, his hand stretched towards the Imam; the others shoved and slipped like landlubbers on a pitching deck. My Iraqi companion curled his lip in distaste at the melodrama. ‘Iranian pilgrims,’ he said.

It all goes back to AD 632, when the Prophet Muhammad died and All, his cousin and son-in-law, was beaten to the caliphate, first by Abu Bakr, the Prophet’s father-in-law, and then by Abu Bakr’s successors, Omar and Osman. Ali gave up political and military office, and waited his turn, and the modesty and piety of the Prophet’s time was supplanted, according to some historians, by venality and hedonism. After twenty-five years, following Osman’s brutal murder, Ali was finally elected to the caliphate. But his rule, although virtuous, lasted only until his murder five years later and gave rise to a rift between his followers and Osman’s clan, the Omayyids. The origin of the rift was a dynastic dispute, between supporters of the Prophet’s family, represented by Ali, and the Prophet’s companions, represented by the first three caliphs. It prefigured a rift that continues, between the Shi’as – literally, the ‘partisans of Ali’ – and the Sunnis, the followers of the Sunnah, the tradition of Muhammad.

After Ali’s murder, Hassan, his indolent elder son, struck a deal with the Omayyids. In AD 680 Hassan died and Ali’s younger son, Hossein, took over as head of the Prophet’s descendants. Hossein was pious and brave and he revived his family’s hereditary claim to leadership over Muslims. This brought him into conflict with Yazid, the Omayyid caliph in Damascus. When the residents of Kufa, near Karbala, asked Hossein to liberate them from Yazid, the Imam went out to claim his birthright, setting in train events that led to his martyrdom.

One night, on the eve of the anniversary of Hossein’s death, I put on a borrowed black shirt and took a taxi to a working-class area of south Tehran. The main road where the taxi dropped me was already filling with families and men leading sheep by their forelegs. Cauldrons lay by the side of the road. Everyone wore black; even the little girls wore chadors, an unbuttoned length of black cloth that unflatteringly shrouds the female body. I entered a lane with two-storey brick houses along both sides. There was a crowd at the far end of the street, their backs to us, and their silhouettes were flung across the asphalt. Black bunting had been strung between lampposts. Walking towards the crowd, I fell in step with a middle-aged man who was being followed by his family. I heard him mutter, ‘Hossein …’ He looked shocked and puzzled, as if he’d just received news of the Imam’s martyrdom.

At the far end of the street there was a stage marked out by pot plants. In the middle of the stage was a bowl of water, resting on a green cloth. The middle-aged man’s wife and daughters went to the opposite side of the stage, where the other women and children were gathered under an awning. His teenage son joined a group of young men with gelled hair on the right. To the left was backstage, and an orchestra that consisted of two tombak drums and a trumpet. I stayed on the near side. Suddenly, the men in front of us parted to allow a stream of piss, from a camel trembling bow-legged in the arc lights, to run down the street.

A young trumpeter played a riff and the obscene Damascene appeared stage left. (Everyone recognized Yazid: he wore a cape of red and yellow to accentuate his licentiousness, and he wasn’t wearing so much as a scrap of green, the colour of Islam.) His helmet was surmounted by yellow plumes. His fat face was expressionless. After prowling around, he started to shout evil words into the microphone he was holding, which was connected to a loudspeaker that in turn felt as though it was connected directly to my ear.

Although he ruled the lands of Islam in the name of Islam, Yazid was notorious for his depravity. Today, Iranians loathe him as if he were still malignantly alive. They recall the menagerie of unclean animals such as dogs and monkeys that he is believed to have kept at court. They talk disapprovingly of the ‘coming and going’ – a common euphemism for frenetic sexual activity – for which Damascus was known. It is said that he was as devious as he was deviant.

Perhaps Hossein had reckoned without the deviousness. By the time he and his companions bivouacked at Karbala, near the banks of the Euphrates, the caliph had bribed the inhabitants of Kufa to revoke their support for him. His small force was greatly outnumbered by the army that Shemr, Yazid’s commander, had raised. Shemr had cut off Hossein’s access to the Euphrates, and Mesopotamia in summer is as hot as hell.

Onstage, the players were relating the entreaties, negotiations and moral dilemmas that preceded Hossein’s martyrdom. The women and children in Hossein’s entourage were suffering from the heat. Since there were no women onstage, we learned this from a narrator, a slim, alert version of the man playing Yazid – his brother, perhaps. Suddenly, there was activity stage left and Yazid returned. The actor’s movements and expression were the same, but now he wore green from head to toe. He had changed character and had become Hossein.

As far as I could make out through the echo and distortion, Hossein was relating the anguish that he felt at his decision to fight to the death. In return for fealty to Yazid, he and his companions would be spared, but that would mean living in dishonour, indifferent to God’s will. Then Hossein’s half-brother, Abol Fazl, entered.

The portraits show Abol Fazl to be as god-like as his brother, albeit more windswept. The Abol Fazl before us was shifty and greasy; he would have been convincingly cast as a sheep rustler. He was much shorter than Hossein, whom he clasped repeatedly to his breast as they both wept. Hossein was asking Abol Fazl to fetch water from the river. Both knew that the younger brother stood little chance of surviving his mission.

Abol Fazl leaped onto a mangy grey standing at the side of the street, where the camel had been. (The camel was peripatetic and for hire; it was now appearing on other stages in the neighbourhood.) He steered the horse dexterously around the stage, calming it when its hind legs buckled as it turned on the greasy asphalt. Whenever Abol Fazl approached the awning, the women shrank, while he (holding the microphone in one hand and the reins in the other) declared his love for Hossein and for God. The young men in the audience grinned when the horse broke wind during a break in the music. Their fathers frowned.

The next bit of the story happened offstage. Fighting savagely – I had read this in the books – Abol Fazl reached the riverside. He bent down, cupped his hand and brought some water to his mouth. Then he stopped himself and the water flowed back through his fingers. His sense of chivalry wouldn’t allow him to slake his thirst before the women and children had slaked theirs. Having filled his leather water container, he remounted, but was cut down in the subsequent struggle, losing his hands and eyes. He cried out, ‘Oh brother, hear my call and come to my aid!’ Two arrows were dispatched. One pierced Abol Fazl’s water container. The other entered his chest.

Abol Fazl staggered onstage. The pierced flagon was between his teeth. An arrow protruded from his chest. His arms were two very long stumps. The stumps supported two bloody objects, which he dropped for us to see: his hands, sliced off in the fray. The Imam cradled the dying Abol Fazl. The men near me in the audience were beating their chests in time with the tombak. The women under the awning rocked inconsolably.

And that was the end of the play. It wasn’t time for Hossein to die; that would come tomorrow, the day that is called Ashura. The actors picked themselves up and left the stage. Among the audience, there was a rustling, a rearranging of positions and a collective, audible exhalation. And then, to my surprise, the inconsolable found consolation. Facial expressions brightened. The audience’s agony changed to equanimity, even satisfaction. The man in front of me greeted the person standing next to him agreeably; a few seconds before, both had been blubbing like children. In the women’s section, conversations began. Abol Fazl seemed to have been forgotten.

Had he been forgotten? Was this grief deceitful? Not deceitful, I think: simply not exclusive. The emotions in Iran haven’t been compartmentalised. They coexist; they thrive in public. The borders between grief, entertainment and companionship are porous. You can weep buckets, natter with a neighbour and take away memories of a farting nag. Stifled sobs, trembling upper lips – they don’t exist here. Emotion may be cheaply expressed, but that doesn’t mean the emotions are cheap.

Some members of the audience were starting to leave their places. The narrator strode into the middle of the stage. He addressed us fluently, softly. He craved our indulgence – he wanted to tell a story that would live in our memories. The people moved back to their places and he began.

A few years back, he started, after the troupe had performed the play we’d just seen, he’d been delighted when a man dropped a large sum of money onto the green cloth in the middle of the stage. As he was counting it after the performance, another man had approached and said, ‘Excuse me for interfering, but you can’t accept that money.’

The narrator had replied: ‘Why not? It’s a lot of money, and I’ve got a wife and kids to feed. It pleases God when money is accepted for good work.’ The man replied, ‘Believe me, sir, you can’t accept this money. Yours is Muslim work, and the man who gave you the money is a Christian. He’s Armenian.’

The audience was gripped. What a dilemma! What would you do in such a situation? The narrator went on: ‘The Armenian chap was driving off when I ran up to him and thrust the money through the open window of his car. I said, “I’m sorry; I can’t accept this money. Forgive me, by the soul of the Imam Hossein, I can’t accept.”’

When he learned why his money had been rejected, the Armenian had switched off the car ignition and said, ‘I have something to tell you.

‘Recently, I was driving with one of my employees, a Muslim, and the brakes failed as we were coming down from the mountains. There were valleys on both sides, and we were going faster and faster. I called out, “Oh Jesus! Save us!” and tried the brakes again, but they didn’t work. I called out a second time, louder, and rammed my foot down on the brakes. Nothing. A third time, I beseeched Jesus to save us. Again, no result.

‘Panic-struck, I looked across at my employee. He said quietly, “Call for Abol Fazl.” I was having trouble keeping the car on the road. I shouted, “Who’s Abol Fazl?” He said, “Sir, time is running out. Call him!” I had nothing to lose, so I shouted, “Save us, Abol Fazl!” and the brakes suddenly worked. We came to a halt just short of a cliff.

‘When we got out of the car, I asked my employee if he’d seen a man on the road, as we were braking. He shook his head. I told him that there had been a man wearing green, and that he had no hands.’

The narrator paused. He bowed his head and emitted three sobs. Then he wiped his eyes and his tone became diffident. ‘Estimable brothers and sisters, you may wish to express your appreciation, and it doesn’t matter how much you put on the green cloth …’ – he went on to list sundry denominations, all of which were beyond the means of those present. ‘No, the amount doesn’t matter. But if, during the course of the coming year, you request Abol Fazl’s intercession and he doesn’t answer, take the matter up with me …’

Nudged by their mothers, the little boys and girls came across to our side of the stage, to get money from their fathers. Then they went over to the cloth and knelt down to kiss and touch it – it had an association, however tenuous, with the Imam Hossein, and few in the audience had the means to go to Karbala. They dropped their money. Once the cloth was covered with notes, men appeared holding trays laden with refreshments. They’d been provided, we learned, by a local trader called Mr Naji. His philanthropy would earn him friends in this life and divine favour in the next.

There were cakes and cucumbers laden high on a copper plate, cinnamon-flavoured rice puddings and little stork’s bundles containing deep-fried white candies seasoned with rose water. There was a ewer pouring water into plastic cups, a loop of tea from the spout of a kettle. In her determination to get a rice pudding, a woman elbowed me in the face. I escaped from the crowd.

Rubbing my jaw, I walked away into a nearby side street. The piercing notes of the orchestra had been succeeded by a mellow, distant sound. Gradually, it grew closer and I was able to distinguish individual sounds within it: hands striking chests, a tremor of lamentation and the diesel motors on generators that were amplifying the lamentation. The processions had started.

Suddenly, I heard a scramble of words through a loudspeaker, and the boom of a bass drum. I looked back up the humdrum street, with its box-like parked cars and unsanitary smell coming from the drainage channels, and saw an army of mounted men on the brow of a hill. Their lances scintillated in the lamplight as they prepared to charge and meet their doom.

The army turned out to consist of a man carrying an iron standard, along whose considerable length oscillated swords and gargoyles and plumes of different colours. He was followed by two columns of men, marching in time with the base drum, flagellating their backs with chains on short handles – a strike for every ponderous beat. A man held up an unintended cross that was composed of two loudspeakers tied to a pole; they were wired to a microphone held by a wailing man a few paces behind.

I had to squeeze up against the wall to make room for the standard to pass. The bearer was thickset, bulging and tight-lipped in his task. He was bound to his panoply from a buckle on a thick belt around his waist. As he passed, he half-slipped, and the weight of the standard pulled him towards me. Thinking I might get hit, I ducked into a side alley.

Once the man had passed, I followed the procession to the main road, where it entered a string of processions, a dozen or more from different neighbourhoods. They were united, and also in competition with each other. The people along the pavements would decide which procession was biggest, and which had the most impressive standard. Had the flagellants been equipped with one chain or two? (From that, you could gauge the benefactor’s generosity.)