Полная версия:

Crash: The Collector’s Edition

‘In February 1972, two weeks after completing Crash, I was involved in my only serious car accident. After a front-wheel blowout my Ford Zephyr veered to the right, crossed the central reservation [ . . . ] and then rolled over and continued upside-down along the oncoming lane. Fortunately I was wearing a seat belt and no other vehicle was involved. An extreme case of nature imitating art.’

J. G. Ballard

CONTENTS

Cover

Epigraph

Copyright

Crash (1973)

‘Jim’s Desk’ by Chris Beckett

Short Stories (1969–70)

‘Crash!’

‘Tolerances of the Human Face’

‘Coitus 80’

‘Journey Across a Crater’

‘Princess Margaret’s Face Lift’

‘Mae West’s Reduction Mammoplasty’

Crash! BBC short film, directed by Harley Cokeliss (1971)

‘The Obsession of a Writer’: Initial treatment

Letter: Ballard to Cokeliss

Draft script by Ballard

J. G. Ballard: Introduction to the French edition of Crash (1974)

J. G. Ballard in conversation with Will Self (1994, extract)

Bibliographical note

Illustration credits

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

COPYRIGHT

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2017

Edited by Chris Beckett

Crash first published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape in 1973

Copyright © J. G. Ballard 1973

The right of J. G. Ballard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All archive material reproduced from British Library collections

copyright © 2017 J. G. Ballard Estate Ltd.

‘Jim’s Desk’ and introductory notes © Chris Beckett 2017

‘Crash!’, first published by Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1969

and subsequently in The Atrocity Exhibition © J. G. Ballard 1969. ‘Tolerances of the Human Face’, first published in Encounter, 1969, and subsequently in The Atrocity Exhibition © J. G. Ballard 1969. ‘Coitus 80’, ‘Journey Across a Crater’ and ‘Princess Margaret’s Face Lift’, first published in New Worlds, January, February, March 1970 © J. G. Ballard 1970. ‘Mae West’s Reduction Mammoplasty’, first published in Ambit, summer 1970 © J. G. Ballard 1970. Introduction to French edition of Crash © J. G. Ballard 1974.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780007378340

Ebook Edition © March 2017 ISBN: 9780008257316

Version: 2017-03-16

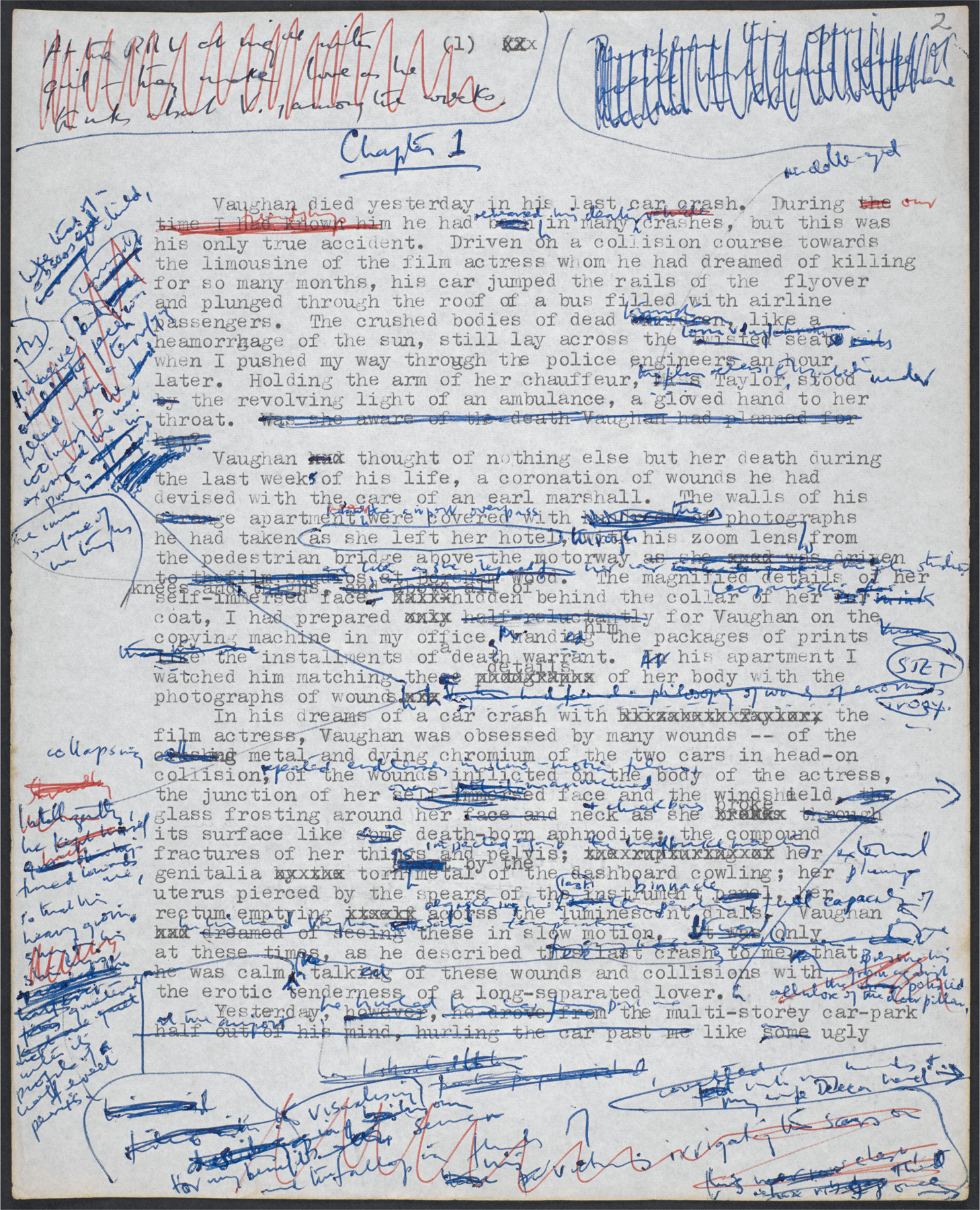

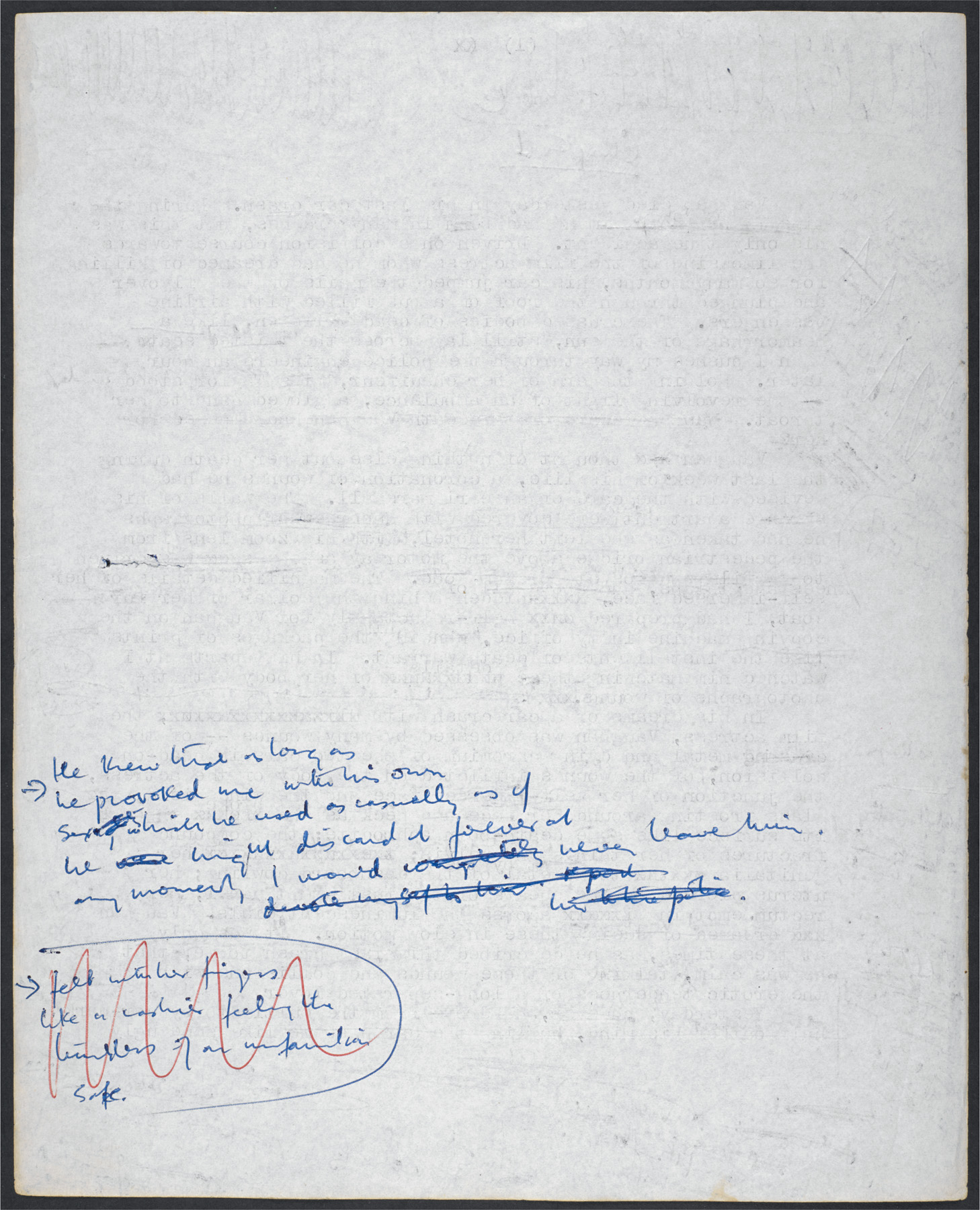

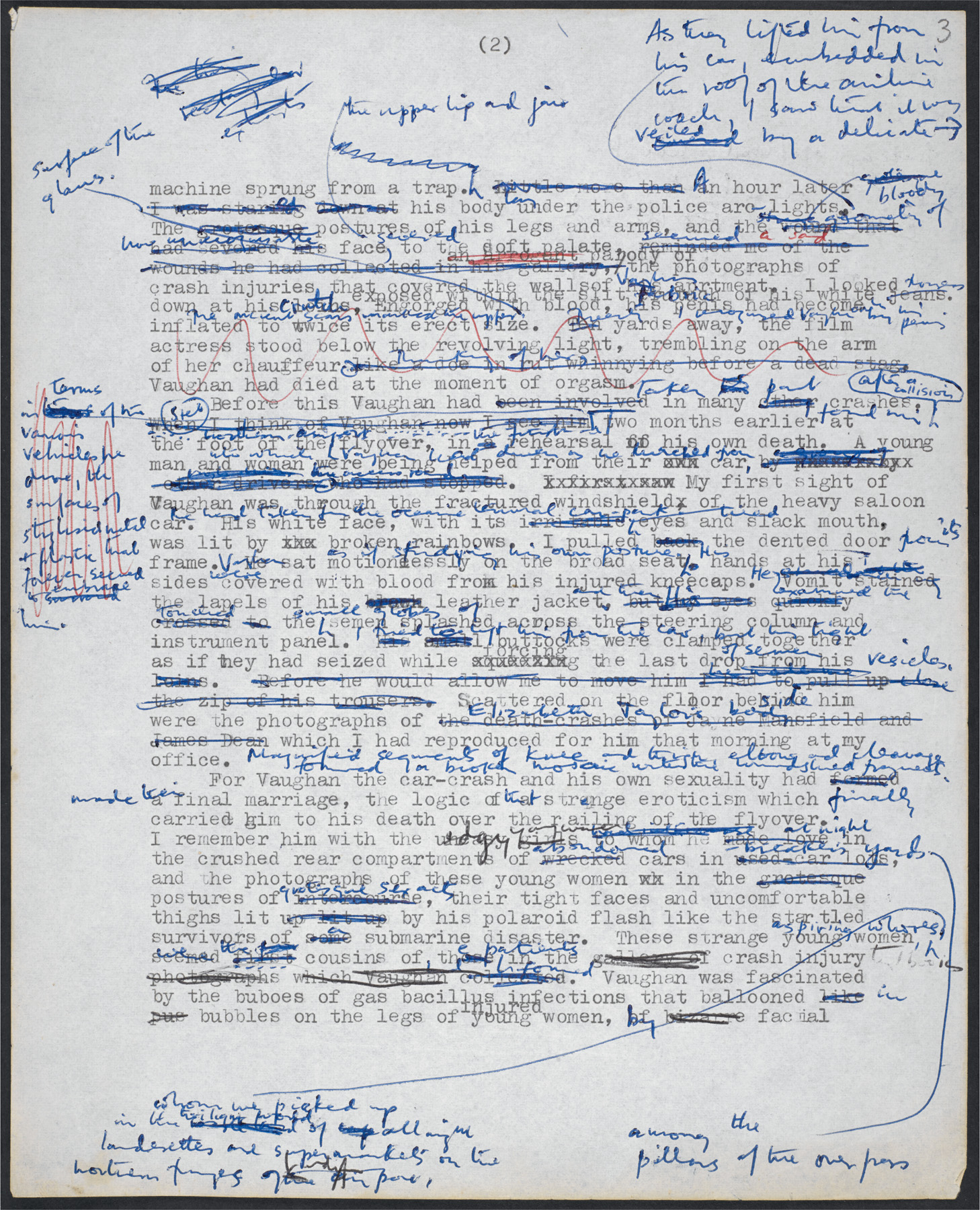

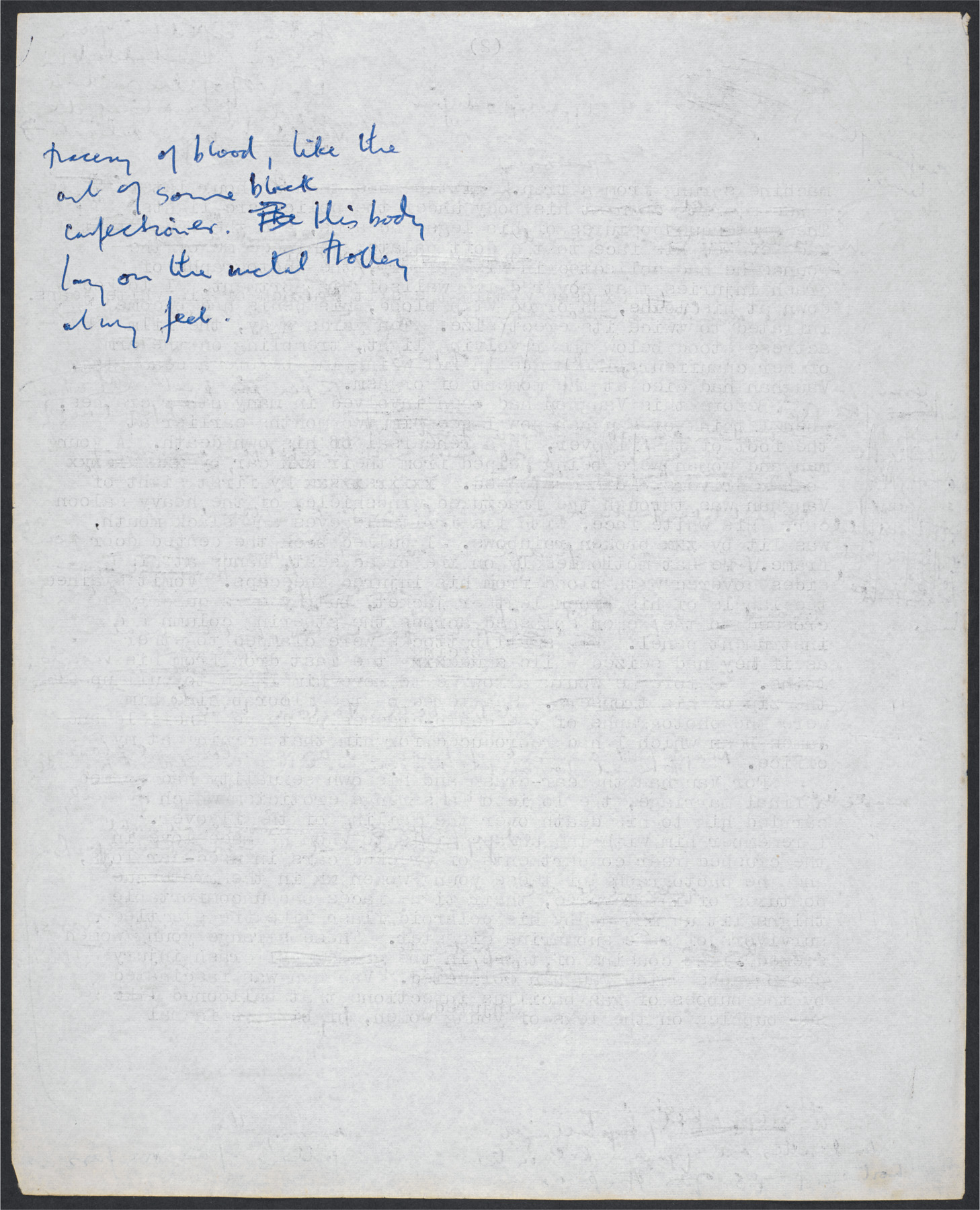

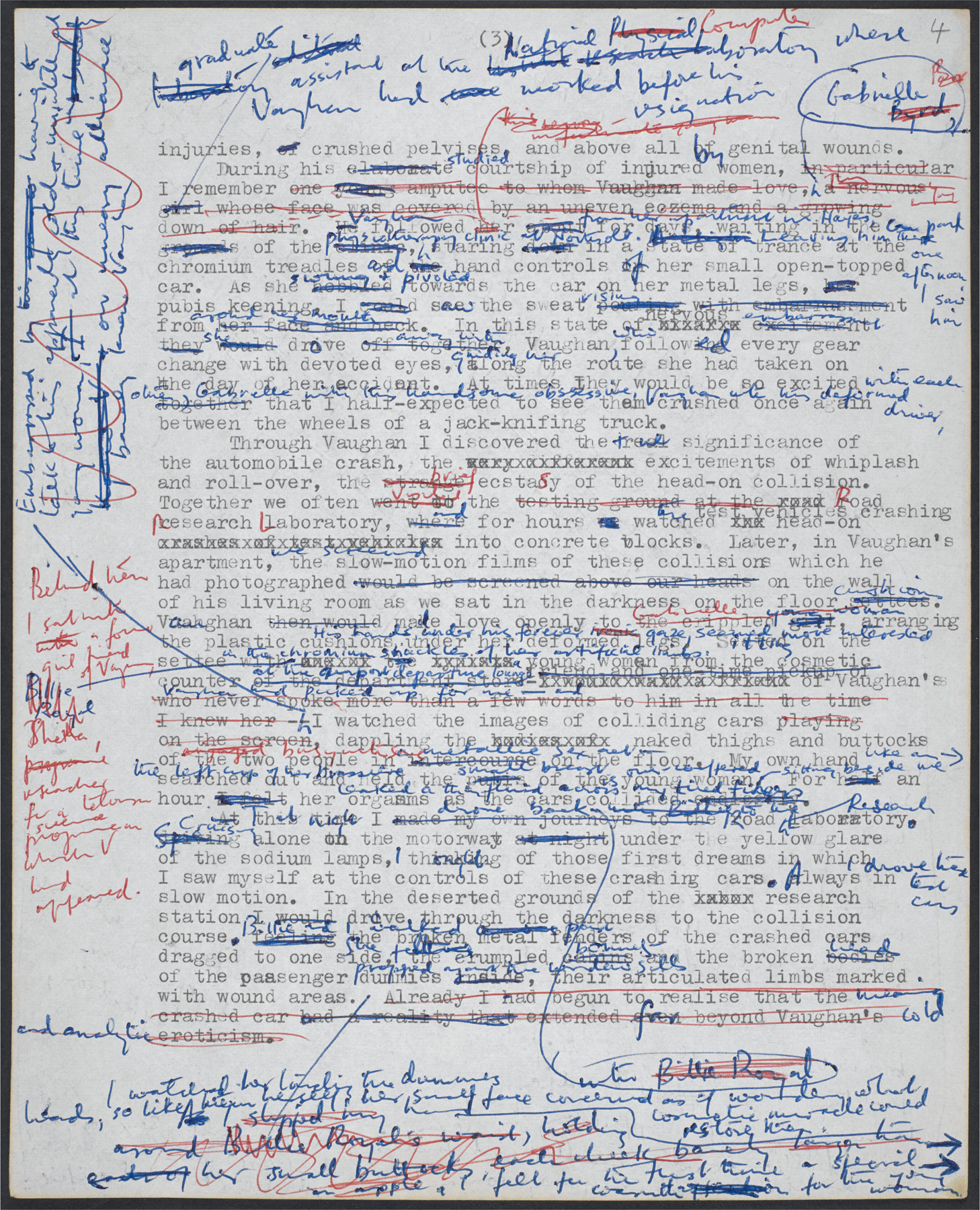

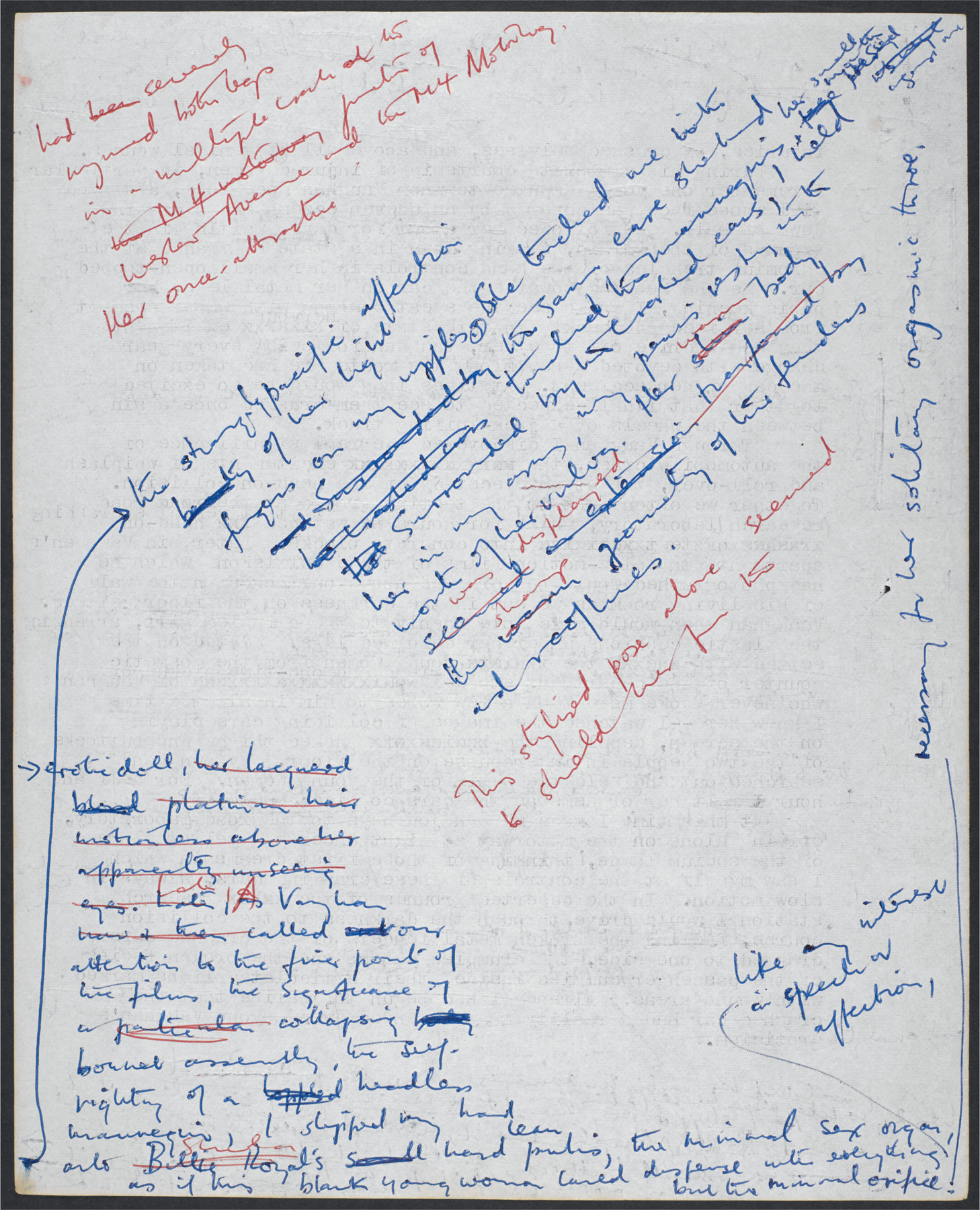

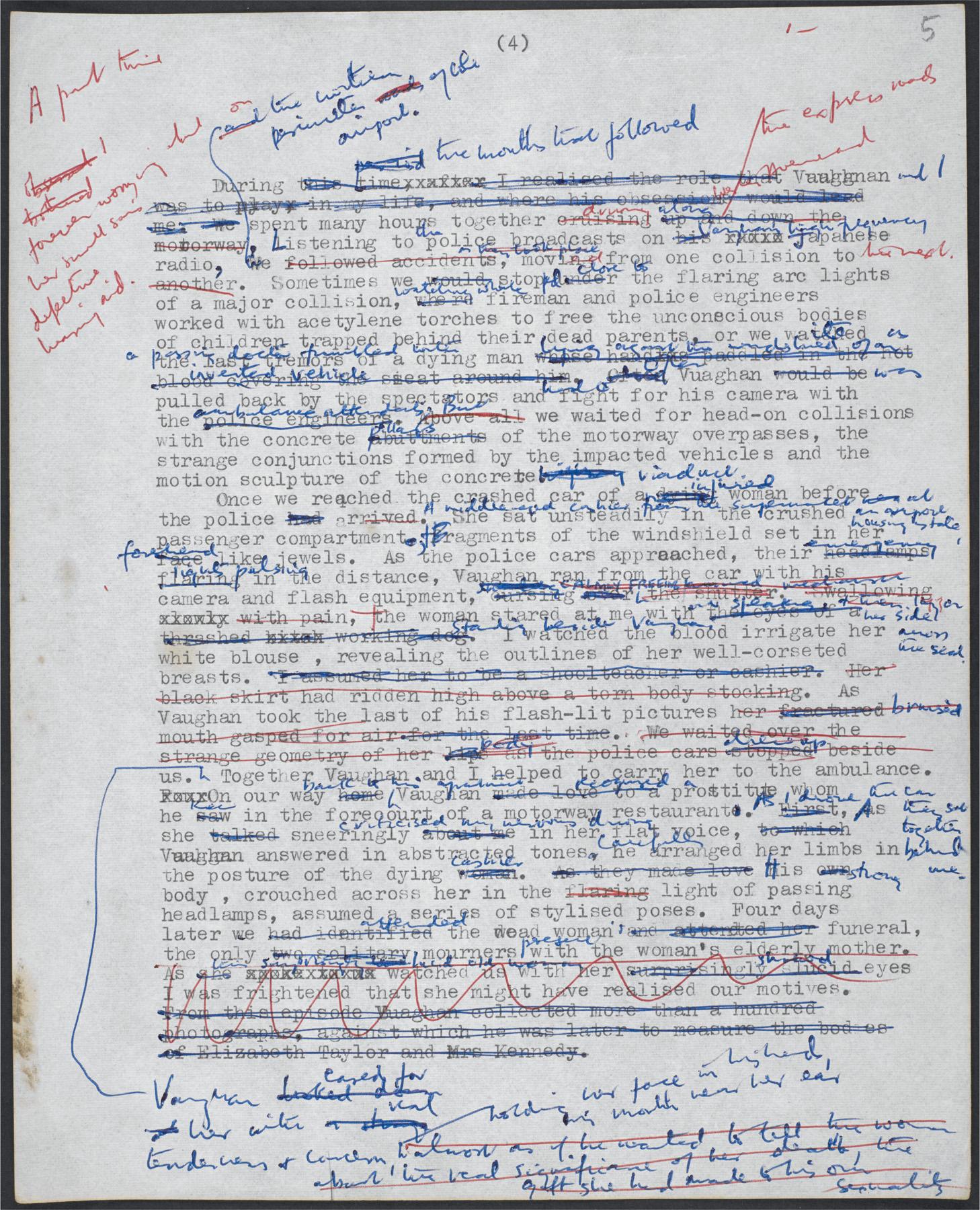

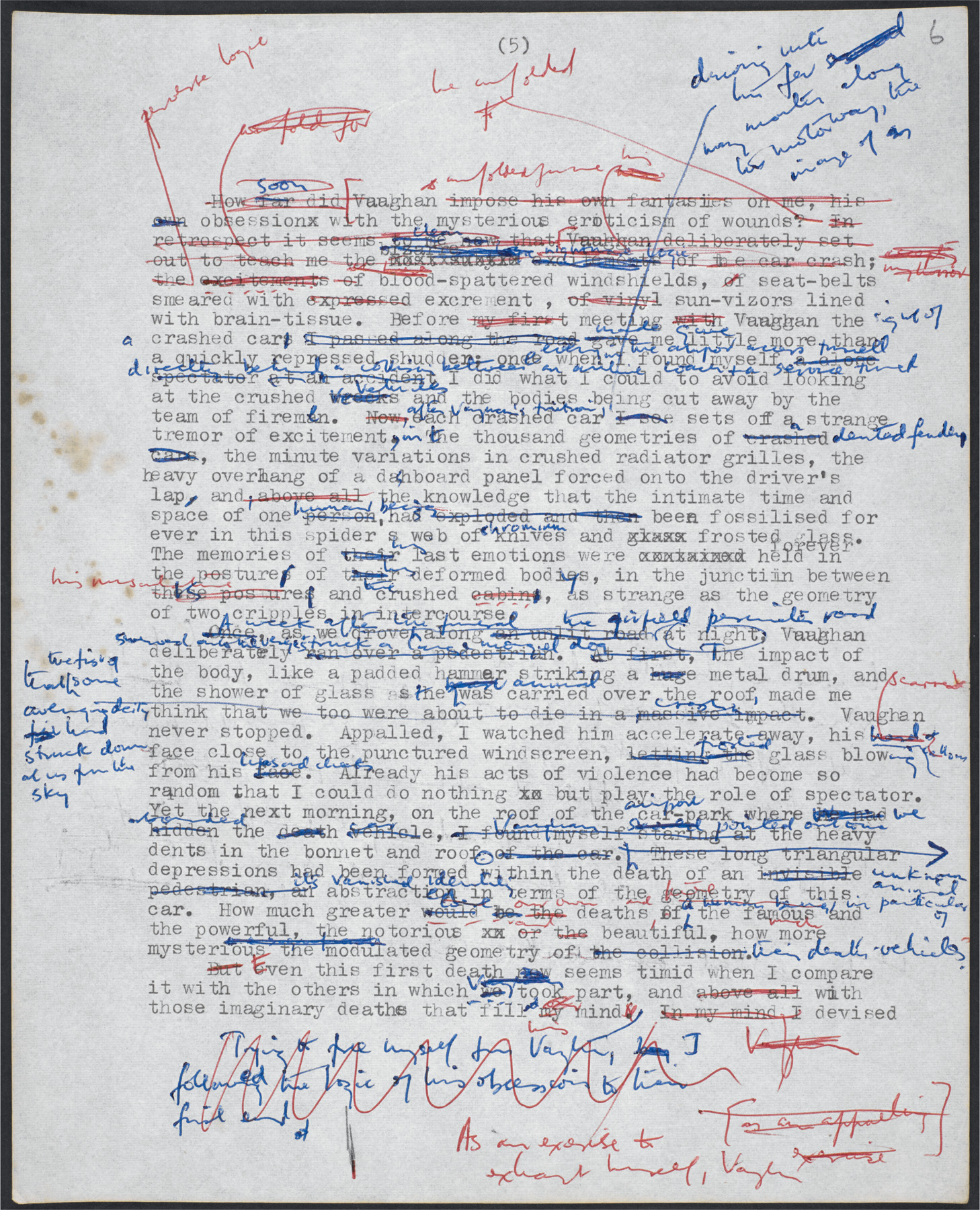

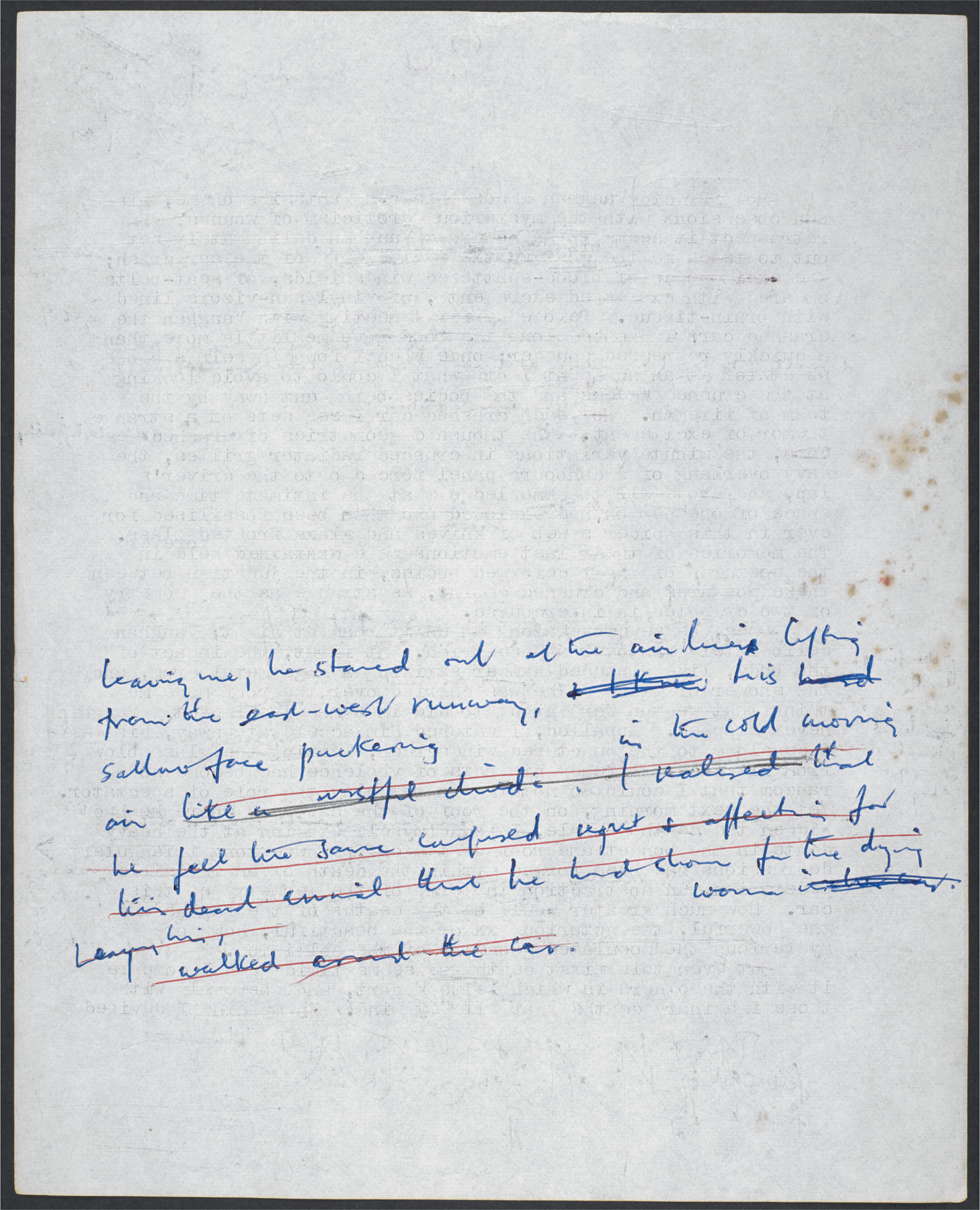

This edition of Crash incorporates five extracts from the earlier of two draft manuscripts held at the British Library (BL Add MS 88938/3/8/1). The selections, which sometimes include autograph material on the backs of pages, are from chapters 1, 7, 17, 21 (numbered 22 in the draft) and 24 (25 in the draft). All selections correspond to the start of a chapter and precede the published text, except the third selection (Chapter 17, the car wash episode) which commences mid-chapter and has been placed at the end of the chapter:

draft pp. 1–5 correspond to Crash pp. 1–7 draft pp. 57–65 correspond to Crash pp. 77–87 draft pp. 167–73 correspond to Crash pp. 177–82 draft pp. 230–5 correspond to Crash pp. 227–37 draft pp. 257–62 correspond to Crash pp. 261–6

1

Vaughan died yesterday in his last car-crash. During our friendship he had rehearsed his death in many crashes, but this was his only true accident. Driven on a collision course towards the limousine of the film actress, his car jumped the rails of the London Airport flyover and plunged through the roof of a bus filled with airline passengers. The crushed bodies of package tourists, like a haemorrhage of the sun, still lay across the vinyl seats when I pushed my way through the police engineers an hour later. Holding the arm of her chauffeur, the film actress Elizabeth Taylor, with whom Vaughan had dreamed of dying for so many months, stood alone under the revolving ambulance lights. As I knelt over Vaughan’s body she placed a gloved hand to her throat.

Could she see, in Vaughan’s posture, the formula of the death which he had devised for her? During the last weeks of his life Vaughan thought of nothing else but her death, a coronation of wounds he had staged with the devotion of an Earl Marshal. The walls of his apartment near the film studios at Shepperton were covered with the photographs he had taken through his zoom lens each morning as she left her hotel in London, from the pedestrian bridges above the westbound motorways, and from the roof of the multi-storey car-park at the studios. The magnified details of her knees and hands, of the inner surface of her thighs and the left apex of her mouth, I uneasily prepared for Vaughan on the copying machine in my office, handing him the packages of prints as if they were the instalments of a death warrant. At his apartment I watched him matching the details of her body with the photographs of grotesque wounds in a textbook of plastic surgery.

In his vision of a car-crash with the actress, Vaughan was obsessed by many wounds and impacts – by the dying chromium and collapsing bulkheads of their two cars meeting head-on in complex collisions endlessly repeated in slow-motion films, by the identical wounds inflicted on their bodies, by the image of windshield glass frosting around her face as she broke its tinted surface like a death-born Aphrodite, by the compound fractures of their thighs impacted against their handbrake mountings, and above all by the wounds to their genitalia, her uterus pierced by the heraldic beak of the manufacturer’s medallion, his semen emptying across the luminescent dials that registered for ever the last temperature and fuel levels of the engine.

It was only at these times, as he described this last crash to me, that Vaughan was calm. He talked of these wounds and collisions with the erotic tenderness of a long-separated lover. Searching through the photographs in his apartment, he half turned towards me, so that his heavy groin quietened me with its profile of an almost erect penis. He knew that as long as he provoked me with his own sex, which he used casually as if he might discard it for ever at any moment, I would never leave him.

Ten days ago, as he stole my car from the garage of my apartment house, Vaughan hurtled up the concrete ramp, an ugly machine sprung from a trap. Yesterday his body lay under the police arc-lights at the foot of the flyover, veiled by a delicate lacework of blood. The broken postures of his legs and arms, the bloody geometry of his face, seemed to parody the photographs of crash injuries that covered the walls of his apartment. I looked down for the last time at his huge groin, engorged with blood. Twenty yards away, illuminated by the revolving lamps, the actress hovered on the arm of her chauffeur. Vaughan had dreamed of dying at the moment of her orgasm.

Before his death Vaughan had taken part in many crashes. As I think of Vaughan I see him in the stolen cars he drove and damaged, the surfaces of deformed metal and plastic that for ever embraced him. Two months earlier I found him on the lower deck of the airport flyover after the first rehearsal of his own death. A taxi driver helped two shaken air hostesses from a small car into which Vaughan had collided as he lurched from the mouth of a concealed access road. As I ran across to Vaughan I saw him through the fractured windshield of the white convertible he had taken from the car-park of the Oceanic Terminal. His exhausted face, with its scarred mouth, was lit by broken rainbows. I pulled the dented passenger door from its frame. Vaughan sat on the glass-covered seat, studying his own posture with a complacent gaze. His hands, palms upwards at his sides, were covered with blood from his injured knee-caps. He examined the vomit staining the lapels of his leather jacket, and reached forward to touch the globes of semen clinging to the instrument binnacle. I tried to lift him from the car, but his tight buttocks were clamped together as if they had seized while forcing the last drops of fluid from his seminal vesicles. On the seat beside him were the torn photographs of the film actress which I had reproduced for him that morning at my office. Magnified sections of lip and eyebrow, elbow and cleavage formed a broken mosaic.

For Vaughan the car-crash and his own sexuality had made their final marriage. I remember him at night with nervous young women in the crushed rear compartments of abandoned cars in breakers’ yards, and their photographs in the postures of uneasy sex acts. Their tight faces and strained thighs were lit by his polaroid flash, like startled survivors of a submarine disaster. These aspiring whores, whom Vaughan met in the all-night cafés and supermarkets of London Airport, were the first cousins of the patients illustrated in his surgical textbooks. During his studied courtship of injured women, Vaughan was obsessed with the buboes of gas bacillus infections, by facial injuries and genital wounds.

Through Vaughan I discovered the true significance of the automobile crash, the meaning of whiplash injuries and rollover, the ecstasies of head-on collisions. Together we visited the Road Research Laboratory twenty miles to the west of London, and watched the calibrated vehicles crashing into the concrete target blocks. Later, in his apartment, Vaughan screened slow-motion films of test collisions that he had photographed with his cine-camera. Sitting in the darkness on the floor cushions, we watched the silent impacts flicker on the wall above our heads. The repeated sequences of crashing cars first calmed and then aroused me. Cruising alone on the motorway under the yellow glare of the sodium lights, I thought of myself at the controls of these impacting vehicles.

During the months that followed, Vaughan and I spent many hours driving along the express highways on the northern perimeter of the airport. On the calm summer evenings these fast boulevards became a zone of nightmare collisions. Listening to the police broadcasts on Vaughan’s radio, we moved from one accident to the next. Often we stopped under arc-lights that flared over the sites of major collisions, watching while firemen and police engineers worked with acetylene torches and lifting tackle to free unconscious wives trapped beside their dead husbands, or waited as a passing doctor fumbled with a dying man pinned below an inverted truck. Sometimes Vaughan was pulled back by the other spectators, and fought for his cameras with the ambulance attendants. Above all, Vaughan waited for head-on collisions with the concrete pillars of the motorway overpasses, the melancholy conjunction formed by a crushed vehicle abandoned on the grass verge and the serene motion sculpture of the concrete.

Once we were the first to reach the crashed car of an injured woman driver. A middle-aged cashier at the airport duty-free liquor store, she sat unsteadily in the crushed compartment, fragments of the tinted windshield set in her forehead like jewels. As a police car approached, its emergency beacon pulsing along the overhead motorway, Vaughan ran back for his camera and flash equipment. Taking off my tie, I searched helplessly for the woman’s wounds. She stared at me without speaking, and lay on her side across the seat. I watched the blood irrigate her white blouse. When Vaughan had taken the last of his pictures he knelt down inside the car and held her face carefully in his hands, whispering into her ear. Together we helped to lift her on to the ambulance trolley.

On our way to Vaughan’s apartment he recognized an airport whore waiting in the forecourt of a motorway restaurant, a part-time cinema usherette for ever worrying about her small son’s defective hearing-aid. As they sat behind me she complained to Vaughan about my nervous driving, but he was watching her movements with an abstracted gaze, almost encouraging her to gesture with her hands and knees. On the deserted roof of a Northolt multi-storey car-park I waited by the balustrade. In the rear seat of the car Vaughan arranged her limbs in the posture of the dying cashier. His strong body, crouched across her in the reflected light of passing headlamps, assumed a series of stylized positions.

Vaughan unfolded for me all his obsessions with the mysterious eroticism of wounds: the perverse logic of blood-soaked instrument panels, seat-belts smeared with excrement, sun-visors lined with brain tissue. For Vaughan each crashed car set off a tremor of excitement, in the complex geometries of a dented fender, in the unexpected variations of crushed radiator grilles, in the grotesque overhang of an instrument panel forced on to a driver’s crotch as if in some calibrated act of machine fellatio. The intimate time and space of a single human being had been fossilized for ever in this web of chromium knives and frosted glass.

A week after the funeral of the woman cashier, as we drove at night along the western perimeter of the airport, Vaughan swerved on to the verge and struck a large mongrel dog. The impact of its body, like a padded hammer, and the shower of glass as the animal was carried over the roof, convinced me that we were about to die in a crash. Vaughan never stopped. I watched him accelerate away, his scarred face held close to the punctured windshield, angrily brushing the beads of frosted glass from his cheeks. Already his acts of violence had become so random that I was no more than a captive spectator. Yet the next morning, on the roof of the airport car-park where we abandoned the car, Vaughan calmly pointed out to me the deep dents in the bonnet and roof. He stared at an airliner filled with tourists lifting into the western sky, his sallow face puckering like a wistful child’s. The long triangular grooves on the car had been formed within the death of an unknown creature, its vanished identity abstracted in terms of the geometry of this vehicle. How much more mysterious would be our own deaths, and those of the famous and powerful?

Even this first death seemed timid compared with the others in which Vaughan took part, and with those imaginary deaths that filled his mind. Trying to exhaust himself, Vaughan devised a terrifying almanac of imaginary automobile disasters and insane wounds – the lungs of elderly men punctured by door handles, the chests of young women impaled by steering-columns, the cheeks of handsome youths pierced by the chromium latches of quarter-lights. For him these wounds were the keys to a new sexuality born from a perverse technology. The images of these wounds hung in the gallery of his mind like exhibits in the museum of a slaughterhouse.

Thinking of Vaughan now, drowning in his own blood under the police arc-lights, I remember the countless imaginary disasters he described as we cruised together along the airport expressways. He dreamed of ambassadorial limousines crashing into jack-knifing butane tankers, of taxis filled with celebrating children colliding head-on below the bright display windows of deserted supermarkets. He dreamed of alienated brothers and sisters, by chance meeting each other on collision courses on the access roads of petrochemical plants, their unconscious incest made explicit in this colliding metal, in the haemorrhages of their brain tissue flowering beneath the aluminized compression chambers and reaction vessels. Vaughan devised the massive rear-end collisions of sworn enemies, hate-deaths celebrated in the engine fuel burning in wayside ditches, paintwork boiling through the dull afternoon sunlight of provincial towns. He visualized the specialized crashes of escaping criminals, of off-duty hotel receptionists trapped between their steering wheels and the laps of their lovers whom they were masturbating. He thought of the crashes of honeymoon couples, seated together after their impacts with the rear suspension units of runaway sugar-tankers. He thought of the crashes of automobile stylists, the most abstract of all possible deaths, wounded in their cars with promiscuous laboratory technicians.

Vaughan elaborated endless variations on these collisions, thinking first of a repetition of head-on collisions: a child-molester and an overworked doctor re-enacting their deaths first in head-on collision and then in roll-over; the retired prostitute crashing into a concrete motorway parapet, her overweight body propelled through the fractured windshield, menopausal loins torn on the chromium bonnet mascot. Her blood would cross the over-white concrete of the evening embankment, haunting for ever the mind of a police mechanic who carried the pieces of her body in a yellow plastic shroud. Alternatively, Vaughan saw her hit by a reversing truck in a motorway fuelling area, crushed against the nearside door of her car as she bent down to loosen her right shoe, the contours of her body buried within the bloody mould of the door panel. He saw her hurtling through the rails of the flyover and dying as Vaughan himself would later die, plunging through the roof of an airline coach, its cargo of complacent destinations multiplied by the death of this myopic middle-aged woman. He saw her hit by a speeding taxi as she stepped out of her car to relieve herself in a wayside latrine, her body whirled a hundred feet away in a spray of urine and blood.

I think now of the other crashes we visualized, absurd deaths of the wounded, maimed and distraught. I think of the crashes of psychopaths, implausible accidents carried out with venom and self-disgust, vicious multiple collisions contrived in stolen cars on evening freeways among tired office-workers. I think of the absurd crashes of neurasthenic housewives returning from their VD clinics, hitting parked cars in suburban high streets. I think of the crashes of excited schizophrenics colliding head-on into stalled laundry vans in one-way streets; of manic-depressives crushed while making pointless U-turns on motorway access roads; of luckless paranoids driving at full speed into the brick walls at the ends of known culs-de-sac; of sadistic charge nurses decapitated in inverted crashes on complex interchanges; of lesbian supermarket manageresses burning to death in the collapsed frames of their midget cars before the stoical eyes of middle-aged firemen; of autistic children crushed in rear-end collisions, their eyes less wounded in death; of buses filled with mental defectives drowning together stoically in roadside industrial canals.

Long before Vaughan died I had begun to think of my own death. With whom would I die, and in what role – psychopath, neurasthenic, absconding criminal? Vaughan dreamed endlessly of the deaths of the famous, inventing imaginary crashes for them. Around the deaths of James Dean and Albert Camus, Jayne Mansfield and John Kennedy he had woven elaborate fantasies. His imagination was a target gallery of screen actresses, politicians, business tycoons and television executives. Vaughan followed them everywhere with his camera, zoom lens watching from the observation platform of the Oceanic Terminal at the airport, from hotel mezzanine balconies and studio car-parks. For each of them Vaughan devised an optimum auto-death. Onassis and his wife would die in a recreation of the Dealey Plaza assassination. He saw Reagan in a complex rear-end collision, dying a stylized death that expressed Vaughan’s obsession with Reagan’s genital organs, like his obsession with the exquisite transits of the screen actress’s pubis across the vinyl seat covers of hired limousines.

After his last attempt to kill my wife Catherine, I knew that Vaughan had retired finally into his own skull. In this overlit realm ruled by violence and technology he was now driving for ever at a hundred miles an hour along an empty motorway, past deserted filling stations on the edges of wide fields, waiting for a single oncoming car. In his mind Vaughan saw the whole world dying in a simultaneous automobile disaster, millions of vehicles hurled together in a terminal congress of spurting loins and engine coolant.

I remember my first minor collision in a deserted hotel car-park. Disturbed by a police patrol, we had forced ourselves through a hurried sex-act. Reversing out of the park, I struck an unmarked tree. Catherine vomited over my seat. This pool of vomit with its clots of blood like liquid rubies, as viscous and discreet as everything produced by Catherine, still contains for me the essence of the erotic delirium of the car-crash, more exciting than her own rectal and vaginal mucus, as refined as the excrement of a fairy queen, or the minuscule globes of liquid that formed beside the bubbles of her contact lenses. In this magic pool, lifting from her throat like a rare discharge of fluid from the mouth of a remote and mysterious shrine, I saw my own reflection, a mirror of blood, semen and vomit, distilled from a mouth whose contours only a few minutes before had drawn steadily against my penis.

Now that Vaughan has died, we will leave with the others who gathered around him, like a crowd drawn to an injured cripple whose deformed postures reveal the secret formulas of their minds and lives. All of us who knew Vaughan accept the perverse eroticism of the car-crash, as painful as the drawing of an exposed organ through the aperture of a surgical wound. I have watched copulating couples moving along darkened freeways at night, men and women on the verge of orgasm, their cars speeding in a series of inviting trajectories towards the flashing headlamps of the oncoming traffic stream. Young men alone behind the wheels of their first cars, near-wrecks picked up in scrap-yards, masturbate as they move on worn tyres to aimless destinations. After a near collision at a traffic intersection semen jolts across a cracked speedometer dial. Later, the dried residues of that same semen are brushed by the lacquered hair of the first young woman who lies across his lap with her mouth over his penis, one hand on the wheel hurtling the car through the darkness towards a multi-level interchange, the swerving brakes drawing the semen from him as he grazes the tailgate of an articulated truck loaded with colour television sets, his left hand vibrating her clitoris towards orgasm as the headlamps of the truck flare warningly in his rear-view mirror. Later still, he watches as a friend takes a teenage girl in the rear seat. Greasy mechanic’s hands expose her buttocks to the advertisement hoardings that hurl past them. The wet highways flash by in the glare of headlamps and the scream of brake-pads. The shaft of his penis glistens above the girl as he strikes at the frayed plastic roof of the car, marking the yellow fabric with his smegma.