Полная версия:

Unraveling Freedom: The Battle for Democracy on the Homefront During World War I

UNRAVELING FREEDOM

ANN BAUSUM

For Kedron

Text copyright © 2010 Ann Bausum

All rights reserved.

Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the National Geographic Society is prohibited.

PUBLISHED BY THE NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC SOCIETY

John M. Fahey, Jr., President and Chief Executive Officer

Gilbert M. Grosvenor, Chairman of the Board

Tim T. Kelly, President, Global Media Group

John Q. Griffin, Executive Vice President; President, Publishing Nina D. Hoffman, Executive Vice President; President, Book Publishing Group

Melina Gerosa Bellows, Executive Vice President, Children’s Publishing

PREPARED BY THE BOOK DIVISION

Nancy Laties Feresten, Vice President, Editor in Chief, Children’s Books

Jonathan Halling, Design Director, Children’s Publishing

Jennifer Emmett, Executive Editor, Reference and Solo, Children’s Books

Carl Mehler, Director of Maps

R. Gary Colbert, Production Director

Jennifer A. Thornton, Managing Editor

STAFF FOR THIS BOOK

Jennifer Emmett, Editor

Jim Hiscott, Art Director

Lori Epstein, Illustrations Editor

Marty Ittner, Designer

Kate Olesin, Editorial Assistant

Grace Hill, Associate Managing Editor

Lewis R. Bassford, Production Manager

Susan Borke, Legal and Business Affairs

MANUFACTURING AND QUALITY MANAGEMENT

Christopher A. Liedel, Chief Financial Officer

Phillip L. Schlosser, Vice President

Chris Brown, Technical Director

Nicole Elliott, Manager

Rachel Faulise, Manager

A NOTE ON THE DESIGN

The design inspiration for Unraveling Freedom is drawn from the propaganda posters of World War I. You’ll see examples of these bold, graphic pieces on Chapter 2 and Chapter 3. The title text for the book is set in Trade Gothic and Marmalade, and the body text is set in Minion Pro. The palette for the book echoes the colors of the American flag—red, white, and blue. To add new life to old photographs and to draw the eye to the central subject matter of an image, some of the pictures in the book (see, for example, Chapter 3) are silhouetted with a special digital technique that pulls the subject of the photograph forward in the frame, while the background is tinted with a color. The colored diagonal design elements, and the frequent angling of the images contribute to a sense of disruption, of things being off balance. This feeling echoes the turbulent sentiment of the times, brought on by the first global war and the erosion of liberties on the home front.

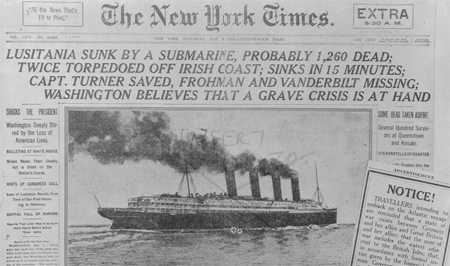

Echoes of history. The September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States (closing endpapers, headline news) prompted the nation’s entry into wars in Iraq and Afghanistan; almost a century earlier, the sinking of the Lusitania helped propel the United States toward combat during World War I. The New York Times coverage of the 1915 maritime disaster (opening endpapers) reproduced a German warning of possible attacks (lower right, headlined “NOTICE!”).

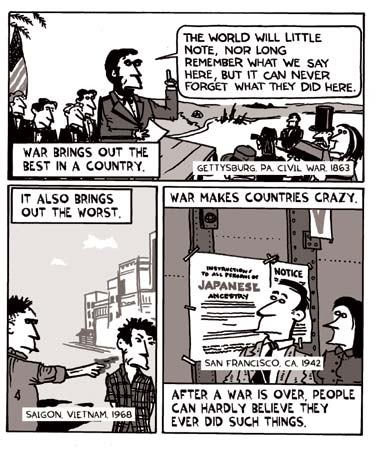

The graphic foreword by Ted Rall, President of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists, evokes the era of political cartooning that flourished during World War I.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bausum, Ann.

Unraveling freedom: the battle for democracy on the home front during World War I / by Ann Bausum.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 978-1-4263-0728-7

1. United States—Politics and government—1913-1921—Juvenile literature. 2. World War, 1914-1918—Social aspects—United States—Juvenile literature. 3. German Americans—Social conditions—20th century—Juvenile literature. I. Title.

E780.B38 2010

940.3’73—dc22

2010010631

Version: 2017-07-05

CONTENTS

Foreword

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 SUNK

CHAPTER 2 A CALL TO ARMS

CHAPTER 3 OFF TO KILL THE HUN

CHAPTER 4 HOLD YOUR TONGUE

CHAPTER 5 BETWEEN WAR AND PEACE

Afterword

Guide to Wartime Presidents

Timeline

Notes and Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Resource Guide

Citations

Illustrations Credits

FOREWORD

BY TED RALL

Ted Rall is President of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists. Visit him online at: http://www.rall.com/

Wilson at war. “It would be the irony of fate if my administration had to deal chiefly with foreign affairs,” observed Woodrow Wilson before his inauguration as President of the United States. The outbreak of war in Europe a year later assured just that.

“We shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest to our hearts [until we] make the world itself at last free.”

WOODROW WILSON, CONCLUDING REMARKS FROM HIS WAR MESSAGE TO CONGRESS, APRIL 2, 1917

INTRODUCTION

IN THE SPRING OF 1917, as the United States prepared to declare war on Germany and enter the fight that would become known as World War I, perhaps as many as a quarter of all Americans had either been born in Germany or had descended from Germans. My grandfather was one of them. But Frederic William Bausum and his family could be considered some of the lucky German-Americans on the eve of war. They spoke English and had no divided loyalty to an old-world country. They had grown up in the United States, married across ethnic lines, homesteaded on the Western plains, and embraced the customs and beliefs of the country. They had, in short, become Americanized.

Thousands of other German-Americans were less fortunate. Almost overnight, the language they spoke by birth, the relatives they retained ties to from their past, the books they read, the schools they attended, even the food and drink they found most familiar and enjoyable, all became associated with the enemy: Germany.

Immigrants and descendants from other places bore ties to competing nations, too, from Great Britain to France to Italy to Russia. U.S. residents who shared backgrounds and beliefs with these countries found themselves taking sides in the conflict at home even as President Woodrow Wilson tried to steer the United States away from joining the conflict abroad. Finally, on April 2, 1917, the President addressed Congress and made a dramatic appeal for the nation to enter the fight. In words that continue to be quoted for their eloquence and passion, Wilson asserted that “the world must be made safe for democracy.”

Yet, in one of the greatest ironies of 20th century U.S. history, the President so committed to securing democracy and freedom abroad failed to prevent the unraveling of freedom in his own country. Even as millions of Americans put on military uniforms and as the nation expended billions of dollars to fund the fight, freedom came under siege in the United States.

Dogs in the fight. Even though the United States remained neutral after fighting broke out in Europe in 1914, Americans followed the conflict between the continent’s leading nations with concern. Dogs became symbols for competing countries, with dachshunds representing Germany. The American bull terrier personified a confident and fearless stand by the United States.

New laws tested the rights of individuals to question and criticize the government. Leaders who spoke from the edges of the political spectrum found themselves ridiculed, harassed, even jailed. A government-sponsored propaganda effort built public support for the war by fanning anti-immigrant feelings within the nation. At a time when Americans fought abroad in the name of freedom and democracy, Americans at home burned German-language books, put German-language newspapers out of business, condemned German foods and drinks, and spied on fellow citizens, especially those with ancestral ties to Germany.

Some of these wrongs took decades to right. Others forever altered the nature of American life—from the nation’s commitment to teaching foreign languages to its tolerance of differences in people from foreign lands. What happens when a segment of the population can be charged with disloyalty simply because of its heritage? Why may democracy go off track when national security seems at risk? How can a nation of immigrants, whose strength comes in part from its diversity, survive the internal conflicts that follow when wars develop with old homelands?

One needs only to look back at history to find questions—and answers—that echo from the past into events of modern times.

1

“The ship was sinking with unbelievable rapidity. There was a terrible panic on her deck. It was the most terrible sight I have ever seen…. The scene was too horrible to watch.”

CAPTAIN WALTHER SCHWIEGER, OF U-BOAT 20, AFTER FIRING A TORPEDO AT THE LUSITANIA

SUNK

It TOOK ONLY 18 MINUTES for the great ship to sink. Even the Titanic had lingered on the ocean surface for more than two hours before sliding to the bottom of the Atlantic in 1912. But, on a sunny spring afternoon just three years later, the Lusitania began to list toward her starboard side almost immediately after being struck by a single submarine-fired torpedo. Minutes later she was gone.

The British ship had been within sight of the Irish coast when U-boat Captain Walther Schwieger commanded his German crew to launch a torpedo at the ocean liner as it steamed past, perhaps 2,300 feet away. It was 2:10 in the afternoon on May 7, 1915. Germany, England, and other European powers had been at war for nine months. Most of the Lusitania’s 1,257 passengers, having eaten their last lunch of the journey, were anticipating their arrival in England the next morning when the 20-foot-long torpedo struck their ship broadside, punching a large hole in the giant vessel’s midsection.

Going down! As the Lusitania sank, the surrounding water became filled with “waving hands and arms belonging to struggling men and frantic women and children,” according to one survivor. The sea “was black with people," observed another.

The Lusitania proved to be an easy target. Despite assurances that she would be greeted in home waters by an armed escort, no such protection materialized as she approached her destination of Liverpool, England, either because none had been requested or because none could be spared by the British Navy. At full speed the Lusitania could easily have outrun any German submarine, but wartime economies had closed one of her four boiler rooms, and the ship’s captain had further reduced her speed for navigation purposes.

Captain William Turner had commanded the Lusitania for only a few months of the ship’s eight-year history, but he had sailed for more than three decades with the vessel’s Cunard Line owner. The 30,000-ton ocean liner had made her maiden voyage in 1907, five years ahead of the Titanic’s single journey. Like the Titanic, the Lusitania promised passengers a swift passage across the Atlantic under luxurious conditions. A crew of more than 700 men and women tended to the needs of passengers during the five to seven days required for a transatlantic crossing. Many crew members on this voyage were new to the service and relatively inexperienced in shipboard safety; they occupied posts held by seamen called up recently for military service.

Battles on the seas. The Lusitania (anchored at New York City in 1907) was one of the world’s fastest ships and symbolized Great Britain’s sea savvy.

When World War I broke out, Great Britain had the largest fleet of military submarines (75 boats). Germany had only 28 U-boats, short for Unterseeboot or underwater boat, but her subs were of more modern design. (U-boat 14).

Early in the war Walther Schwieger, captain of U-boat 20, attacked and sank the Lusitania.

Setting off. Some passengers decided not to sail on the Lusitania after Germany printed warnings in American newspapers of attacks on ships.

Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt had cancelled travel on the Titanic’s maiden voyage three years earlier but sailed as planned on the Lusitania.

Passengers who traveled in first class enjoyed gourmet meals in plush, gilded surroundings. Some suites even had their own wood-burning fireplaces. Facilities in second class were almost as luxurious. Even third-class passengers received courteous service and feasted on a bountiful assortment of specially prepared food. Those who embarked on their trip from the harbor in New York City on May 1, 1915, included the usual complement of celebrities and millionaires. Most notable, perhaps, was Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, descendant of the railroad magnate; he was one of about 200 other Americans bound for England on the Lusitania. Most of the rest of the passengers were British or Canadian. Everyone knew that this transatlantic crossing carried added risks because of the new European war.

Submarines (U-boat 7), earned the nickname the “assassins of the seas.”

In August 1914, soon after Allied forces from such nations as England and France pushed back against Germany’s invasion of Belgium, the Germans began attacking enemy ships with submarines. Submarine warfare was a new idea then, and there was not yet a code of conduct for using this new technology. Which ships could be attacked? Warships, clearly yes. But what about merchant ships carrying cargo and supplies to enemy countries? Or boats that carried passengers and cargo? Should vessels be forewarned of attack so that they could be evacuated? Or could subs attack without warning? Answers remained unclear, and unease developed in February 1915 after Germany announced that it would begin using submarines to attack other ships, whatever their nationality, if they approached British ports. Since then the Germans had sunk 66 commercial ships; 23 had been attacked just since the Lusitania’s departure from New York.

Thus, the first glimpses by passengers of the Irish coast on the morning of May 7 signified both the nearness of their destination and their arrival in dangerous waters. Many people were on one of the Lusitania’s open-air decks as Captain Schwieger prepared to fire at the passing target. A number of survivors could recall their horror upon glimpsing the silhouette of U-boat 20’s periscope above the calm, sunny ocean. They and others stood mesmerized as they realized that the trail of bubbles advancing toward them marked the unstoppable track of a torpedo set to reach its target in less than a minute’s time. Most on board remained oblivious to the approaching danger until they heard and felt the impact of the torpedo.

Captain Schwieger had aimed his torpedo with dead-on accuracy. Had he fired five seconds sooner or 20 seconds later, the weapon would have skimmed past the liner entirely. As it was, the missile hit the ship broadside, inflicting the maximum possible damage and triggering a sequence of catastrophic injuries to the liner. Some substance—probably coal dust—exploded almost immediately after the torpedo struck, widening the hole in the boat’s side. Thousands of gallons of water began rushing into the Lusitania, causing her to list toward the wound on her starboard side. Additional seawater poured in through open portholes and hatches as they fell below the water line, further dragging the ship off balance. Immediately the captain and crew found themselves without enough power or control to stop the vessel’s forward momentum or steer it toward shore.

Within minutes, the ship’s electrical power system failed, plunging passengers and crew still below decks into darkness. Passengers traveling to the upper decks inside electrically powered elevators found themselves permanently trapped. Crew members working in the deepest bowels of the boat—in areas only reachable by electric elevators—became cut off from all reasonable means of escape.

Even those standing on exterior decks faced uncertain exits from the ship. The Titanic tragedy assured that vessels now had ample lifeboats and life jackets, but most life jackets were stowed in passenger cabins, causing people to rush back and forth down crowded and (within minutes) darkened passageways to find them. As the ship listed to one side, baby carriages, some still occupied by infants, careened across the boat’s decks. Furniture, potted plants, and dishes spilled or broke, leaving decks, cabins, and passageways littered with debris. Halls and stairs became obstacle courses as the increasing slant of the ship upended their usual orientations.

Meanwhile the listing of the ship caused lifeboats on the Lusitania’s port side to bump against the vessel’s exterior hull as they were lowered, spilling evacuees into the sea. Often then the empty boats crashed down on victims below. In the end, many passengers and crew members simply jumped into the water. Others were swept overboard. Countless more remained trapped on board when the ship sank out of sight at 2:28 p.m.

“It was freely stated and generally believed that a special effort was to be made to sink [the Lusitania] so as to inspire the world with terror.”

MARGARET MACKWORTH, PASSENGER ON THE LUSITANIA’S FINAL VOYAGE

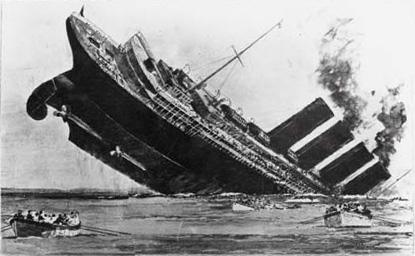

No photographs were made of the sinking ship, so artists dramatized the scene. The New York Herald called the sinking “premeditated slaughter,” but Germans defended the attack, charging that the ship secretly carried war supplies, a claim that the Allies denied.

SOS! “Come at once,” signaled the Lusitania’s wireless operator after the ship was attacked by a German U-boat (a torpedo)

A life jacket did not necessarily assure safety in the water. Many people, in panic or ignorance, had put the devices on upside down or backward. Thus the jacket promptly flipped its wearer head first or face down in the water. Floating wreckage offered sanctuary for some but created life-and-death battles among others. People clung to anything that floated, including dead bodies. Calls for help, screams, and the cries of children filled the air around an ever-widening circle of debris floating in blood-red waters. The chill of the spring Atlantic—probably about 52 degrees—shortened the chances of survival for children and the elderly. Even the hardiest faced death by hypothermia within hours of immersion, if not sooner.

Scenes of wrenching separation and miraculous reunions punctuated the chaotic minutes of the ship’s sinking and the hours of waiting and rescue that followed. Gerda Nielson and John Welsh, who had fallen in love during their journey, were pulled from the water by occupants of a passing lifeboat. Norah Bretherton, a mother traveling alone in second class with two young children, was with neither one of them when the torpedo struck. She found, then lost track of, her 15-month-old daughter before escaping with her son in a lifeboat.

Captain Schwieger’s U-boat was long gone by the time the first rescue ship arrived at the field of floating debris about three and a half hours after the Lusitania had sunk. It took until 8 p.m. for an initial boatload of survivors to travel some 12 miles from the wreckage to the Irish seaport of Queenstown, the impromptu home base for rescue efforts. David Thomas, a former member of the British Parliament, was standing on the docks at 11 p.m., scanning the faces of survivors, when his grown daughter Margaret Mackworth struggled ashore. The pair had become separated following the attack. Captain Turner, who had jumped from his ship as she sank and been pulled from the wreckage hours later, arrived on the same boat. More vessels followed.

On dry land. Survivors struggled to comprehend the trauma they had experienced during the sinking of the Lusitania.