скачать книгу бесплатно

Whether or not that book sees truly into the heart of Shakespeare, it unquestionably reaches to the core of Hughes’s myth. His Daimon took the form of a woman and for that reason, if no other, women play a huge part in the story of his metamorphosis of life into art. It has accordingly been necessary to include a good deal of sensitive biographical material, but this material is presented in service to the poetry. His sister Olwyn said that Ted’s problem, when it came to women, was that he didn’t want to hurt anybody and ended up hurting everybody.38 His friends always spoke of his immense kindness and generosity, but some of his actions were selfish in the extreme and the cause of great pain to people who loved him. I seek to explain and not to condemn. Plath’s biographers have too often played the blame game. Instead of passing moral judgements, this book accepts, as Hughes put it in one of his Birthday Letters poems, that ‘What happens in the heart simply happens.’39 It is for the biographer to present the facts and for readers to draw their own conclusions.

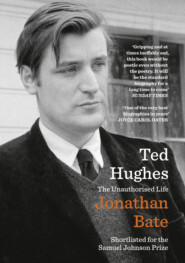

There will be many biographies, but this is the first to mine the full riches of the archive and to tell as much as is currently permissible of the full story, as it was happening, and as it was remembered and reshaped in art, from the point of view of Ted Hughes. His life was, he acknowledged, the existential ‘capital’ for his work as an author. His published writings might be described as the ‘authorised’ version of the story, the life transformed and rendered authorial. His unpublished writings – drafts, sketches, abortive projects, journals, letters – are the place where he showed his workings. He kept them for posterity in their millions of words, most of which have now been made available to the public. The archive is where he is ‘un-authored’, turned back from ‘Famous Poet’ (the title of another of his early poems) to mortal being. Together with the memories of those who knew and loved him, the archive reveals that the way he lived his life was authorised not by social convention or by upbringing, but by his passions, his mental landscape and his unwavering sense of vocation. His was an unauthorised life and so is this.

1

‘fastened into place’ (#ulink_8a3bd3aa-891b-53a9-b80b-2718e7936b3b)

Coming west from Halifax and Sowerby Bridge, along the narrow valley of the river Calder, you see Scout Rock to your left. North-facing, its dense wood and dark grey stone seem always shadowed. The Rock lowers over an industrial village called Mytholmroyd. Myth is going to be important, but so is the careful, dispassionate work of demythologising: the first syllable is pronounced as in ‘my’, not as in ‘myth’. My-th’m-royd.1 For Ted Hughes, it was ‘my’ place as much as a mythic place.

His childhood was dominated by this dark cliff, ‘a wall of rock and steep woods half-way up the sky, just cleared by the winter sun’. This was the perpetual memory of his birthplace; his ‘spiritual midwife’, one of his ‘godfathers’. It was ‘the curtain and back-drop’ to his childhood existence: ‘If a man’s death is held in place by a stone, my birth was fastened into place by that rock, and for my first seven years it pressed its shape and various moods into my brain.’2

Young Ted kept away from Scout Rock. He belonged to the other side of the valley. Once, though, he climbed it with his elder brother, Gerald. They ascended through bracken and birch to a narrow path that braved the edge of the cliff. For six years, he had gazed up at the Rock – or rather, sensed its admonitory gaze upon him – but now, as if through the other end of the telescope, he was looking down on the place of his birth. He stuffed oak-apples into his pockets, observing their corky interior and dusty worm-holes. Some, he threw into space over the cliff.

Gerald, ten years older, lived to shoot. He told his little brother of how a wood pigeon had once been shot in one of the little self-seeding oaks up here on the Rock. It had set its wings ‘and sailed out without a wing-beat stone dead into space to crash two miles away on the other side of the valley’.3 He told, too, of a tramp who, waking from a snooze in the bracken, was mistaken for a fox by a farmer. Shot dead, his body rolled down the slope. A local myth, perhaps.

There was also the story of a family, relatives of the Hugheses, who had farmed the levels above the Rock for generations. Their house was black, as if made of ‘old gravestones and worn-out horse-troughs’. One of them was last seen shooting rabbits near the edge. He ‘took the plunge that the whole valley dreams about and fell to his death down the sheer face’. Thinking back, the adult Hughes regarded this death as ‘a community peace-offering’.4 The valley, he had heard, was notable for its suicides. He blamed the oppression cast by Scout Rock.

He wrote his essay about the Rock at a dark time. It was composed in 1963 as a broadcast for a BBC Home Service series called Writers on Themselves.5 Broadcast three weeks earlier in the same series was a posthumous talk by Sylvia Plath (read by the actress June Tobin) entitled ‘Ocean 1212-W’. The letter in which BBC producer Leonie Cohn suggested this title for the talk was possibly the last that Plath ever received.6 Where the primal substance of Ted’s childhood was rock, that of Sylvia’s was water: ‘My childhood landscape was not land but the end of land – the cold, salt, running hills of the Atlantic … My final memory of the sea is of violence – a still, unhealthily yellow day in 1939, the sea molten, steely-slick, heaving at its leash like a broody animal, evil violets in its eye.’7

Though a suicide far from the Calder Valley preyed on Hughes’s mind as he wrote of the Rock, there is no reason to doubt his memory of its force. Still, whenever writers make art out of the details of their childhood, a part of the reader wonders whether that was really how they felt at the time. Is the act of remembering at some level inventing the memory? William Wordsworth was the great exemplar of this phenomenon. He called his epic of the self a poem ‘on the growth of the poet’s mind’. And it was there that he pondered questions that we should always ask when reading Hughes’s poetry of recollection. What does it mean to dissolve the boundary between the things which we perceive and the things which we have made? What is the relationship between the writing poet and the remembered self? Is a particular memory true because it is an accurate account of a past event or because it is constitutive of the rememberer’s consciousness? Each member of a family remembers differently. Reading a draft of this chapter, Olwyn Hughes was angry: she did not recognise her own childhood, which in her memory was filled with light and laughter, happy family life and the absolute freedom of outdoor play. ‘Hard task’, writes Wordsworth, ‘to analyse a soul.’8

Wordsworth, too, remembered a towering, shadowed rock as a force that supervised and admonished his childhood – the similarity of language in Hughes’s ‘The Rock’ suggests a literary allusion as well as a personal memory. For Wordsworth, the overseer was a cliff face that loomed above him as he rowed a stolen boat across a lake. It cast a shadow of guilt and fear over his filial bond with nature. For Hughes, too, to speak of living in the shadow of the Rock was a way of externalising a darkness in his own heart.

From the Rock, young Ted could also see the arteries leading out to east and west. The railway, fast and slow lines in each direction. The station building was perched on a viaduct. Below, there was the largest goods yard in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Inward goods: wool from Yorkshire and cotton from the Lancashire ports. Outward: clothing and blankets from the mills and sewing shops. Corduroy and flannel, calico and moleskin; men’s trousers in grey or fawn. New fashions: golf jackets, hiking shorts, blue and khaki shirts. The yard was also packed with boxes of chicks and eggs: overrunning the hillside above were chicken sheds belonging to Thornbers, pioneers of factory poultry farming.

Below the railway was the river Calder. A ‘mytholm’ is a meeting of streams. Just by the Co-op and the old Navvy Bridge, the Elphin Brook, darting down from the narrow gully of Cragg Vale, flows into the Calder. Beyond the river was the main road, the old cross-Pennine turnpike – rumbling lorries but some of the traffic still horse-drawn – that linked Halifax to Burnley, Yorkshire to Lancashire. The Calder Valley is on the cusp of the two great counties of northern industrial productivity, with their deep history of rivalry going back to the Wars of the Roses.

On the far side of the road – Ted’s side – ran the Rochdale Canal, still in use for transporting goods, but only just. Now it was a place for the local children to fish for gudgeon and stickleback. Beyond the canal, a network of terraced houses clustered, back to back or back to earth, on the northern hillside. This was the Banksfield neighbourhood, where he and his family belonged. Some of the muck streets went vertically, others (including his own) ran horizontally, in parallel with the canal. The surrounding fields were dotted with smallholders’ hen pens. Scattered above, where the fields sloped gently up to the moors, were farms. The path up the hill to the moor was always there as an escape from the blackened mills and terraces.

Down in the valley, Ted felt secure, if hemmed in. On top of the Rock that day in 1936 or ’37, he was exposed. He looked down on a community that was closed in on itself. Nearly all the buildings were made of the distinctive local stone. Known as millstone grit (‘a soul-grinding sandstone’),9 it oxidises quickly, whatever the condition of the air. Add a century of factory smoke and acid rain. Then, as a tour guide will put it in one of Hughes’s poems about his home valley, ‘you will notice / How the walls are black’.10 This was the cradle of the Industrial Revolution. Everywhere, blackened chimneys known as lumbs rose skyward from the mills.

On his side of the valley, the dark admonitory presence was not a rock but a building. A stone mass towered beside the Hughes family home: the Mount Zion Primitive Methodist Chapel. It was black, it blocked the moon, its façade was like the slab of a gravestone. It was his ‘first world-direction’.11

Number 1 Aspinall Street stands at the end of the terrace. Now you walk in straight off the street; when Ted was a boy, before the road was tarmacked, there was a little front garden where vegetables were grown and the children could play. Go in through the front door and the steep stairs are immediately in front of you. The main room, about 14 feet by 14 feet, is to the left. From the front window the Hughes family could look straight up Jubilee Street to the fields.

There was a cosy little kitchen with a fireplace in the corner and a window looking out on the side wall of Mount Zion. According to Ted’s poem about the chapel, the sun did not emerge from behind it until eleven in the morning. His sister Olwyn, however, recalls the kitchen being bathed in afternoon light. The poems have a tendency to take the darker view of things. By the same account, Olwyn always thought that Ted exaggerated the oppressive height and darkness of the Rock.

A tin bath was stored under the kitchen table. One day Mrs Edith Hughes woke from a dream in which she had bought a bath in Mytholmroyd. She went straight to the shops, where she found one that was affordable because slightly damaged. The back door led to a ginnel, a passageway shared with the terraced row that stood back to back with Aspinall Street. The washing could be hung out here and the children, who spent most of their time playing in the street, could shelter from the rain. Which never seemed to stop.

The kitchen also had a door opening on some steps down to a little cellar, which had a chute where the coal was delivered, the coalman heaving sacks from his horse-drawn cart. Some of the terraces had to make do with a shared privy at the end of the row, but the Hughes family lived at the newer end of Aspinall Street, slightly superior, with the modern amenity of an indoor toilet at the top of the stairs.

Mother and father had the front bedroom and Olwyn the side one, with a window looking out on the chapel. Ted shared an attic room with Gerald. When he stood on the bed and peered out through the little skylight, the dark woods of Scout Rock gave the impression of being immediately outside the glass, pressing in upon him.

This was the house in which Edward James Hughes entered the world at twelve minutes past one in the morning on Sunday 17 August 1930. ‘When he was born,’ his mother Edith remembered, ‘a bright star was shining through the bedroom window (the side bedroom window) he was a lovely plump baby and I felt very proud of him. Sunday was a wet day and Olwyn just could not understand this new comer.’12

Gerald, just a few weeks off his tenth birthday, lent a helping hand. Despite the rain, Edith’s husband Billie went out for a spin in her brother Walter’s car. Minnie, wife of another brother, Albert, who lived along the street at number 19, had offered to look after Olwyn, but she didn’t that first day. A neighbour was called to take in the unsettled two-year-old.

As a teenager, Olwyn would develop a serious interest in astrology, which she shared with Ted. The conjunction of the stars mattered deeply to them.13 He was born at what astrologers call ‘solar midnight’. With knowledge of the exact time and place of his birth, a natal chart could be cast. He was born under the sign of Leo, the lion, which endowed him with a strong sense of self, the desire to shine. But because he was born at solar midnight, he would also need privacy and seclusion. His ‘ascendant’ sign was Cancer, bonding him to home and family. And Neptune, the maker of symbols and myths, was ‘conjunct’. His horoscope, he explained, meant that he was ‘fated to live more or less in the public eye, but as a fish does in air’.14 Bound for fame, that is to say, but fearful of scrutiny.

Did he really believe that his fate was written in the stars? ‘To an outsider,’ he once observed in a book review, ‘astrology is a procession of puerile absurdities, a Babel of gibberish.’ He granted that many astrologers peddled rubbish and craziness. Others, he thought, did make sense. He did not know whether genuine astrology was an ‘esoteric science’ or an ‘intuitive art’. That did not matter, so long as it worked: ‘In a horoscope, cast according to any one of the systems, there are hundreds of factors to be reckoned with, each one interfering with all the others simultaneously, where only judgement of an intuitive sort is going to be able to move, let alone make sense.’15 It is all too easy to select a few out of those hundreds of factors in order to make the horoscope say what you want it to say. Neptune is the sign of many things in addition to symbols and myths, but since Ted Hughes was obsessed with symbols and myths they are the aspect of ascendant Neptune that it seems right to highlight in his natal chart. By the time anyone is old enough to talk about their horoscope, their character is formed; at some level, they have themselves already written the narrative that is then ‘discovered’ in the horoscope. But there is comfort in the sense of discovery. For Ted, astrology, like poetry, was a way of giving order to the chaos of life.

‘Intuitive’ is the key word in Hughes’s reflections on astrology. If the danger of a horoscope is that it is an encouragement to the abnegation of responsibility for one’s own actions, a forgetting of Shakespeare’s ‘the fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, / But in ourselves’, the value of a horoscope is its capacity to confirm one’s best intuitions. The major superstitions – astrology, ghosts, faith-healing, the sixth sense whereby you somehow know that a person you love has died even though they are far away – are, Hughes thought, impressive because ‘they are so old, so unkillable, and so few. If they are pure nonsense, why aren’t there more of them?’16

His birth was formally registered in Hebden Bridge, the nearest large town. Father was recorded as William Henry Hughes, ‘Journeyman Portable Building maker’, that is to say a carpenter specialising in the assembly of sheds, prefabs and outbuildings. Mother was Edith Hughes, formerly Farrar.

William Hughes was born in 1894.17 His father, John, was a fustian dyer, known as ‘Crag Jack’. Family legend made him a local sage – ‘solved people’s problems, wrote their letters, closest friends the local Catholic and Wesleyan Ministers, though he spent a lot of time in pubs’.18 Crag Jack was said to have been a great singer. He was a bit of a ‘mystery man’, who came to the Calder Valley from Manchester and, before that, Ireland. In the young Ted’s imagination, he is perhaps a kind of bard or shaman, certainly a conduit of Celtic blood.

‘Crag Jack’s Apostasy’ is one of the few early Hughes poems to mention his family directly. There Jack clears himself of the dark influence of the church that ‘stooped’ over his ‘cradle’. He finds a god instead beneath the stone of the landscape.19 Here Ted takes on Grandfather Jack’s identity: the cradle stooped over by the dark church is clearly his own, shadowed by Mount Zion.

The story in the family was that Crag Jack died from pneumonia at the age of forty, leaving Willie Hughes a three-year-old orphan, together with his younger brother and elder sister. But there is a little misremembering or exaggeration here. The 1901 census records that John Hughes, aged forty-seven, and his wife Mary were living over a shop in King Street, Hebden Bridge, with their nineteen-year-old daughter, also called Mary, a ‘Machinist Fustian’, and the two boys, John aged eight (born Manchester) and Willie, seven (born Hebden Bridge), together with a young cousin called Elizabeth. Crag Jack died in 1903, closer to the age of fifty than forty. Willie was not three but nearly ten when he lost his father. Ted’s widowed Granny Hughes kept on the King Street shop for many years. She died in her eighties.

Like her husband, she had been born in Manchester. Her father was apparently a major in the regular army, his surname also being Major. His station was Gibraltar, so family tradition knew him as ‘Major Major of the Rock’. He married a short, dark-skinned, ‘Arab looking’ Spanish woman with, according to Ted, a ‘high thin nose like Olwyn’s’.20 This association with Spain and a distant Rock, an outpost of empire overlooking the Mediterranean, gave Ted the idea that he might have some exotic Moorish blood in him. A touch of blackness, akin to that of Emily Brontë’s Heathcliff, found on the streets of Liverpool?

It was the Farrar family, not the Hughes, who dominated Ted’s childhood. In May 1920, Willie married Edith Farrar, who was five months pregnant with Gerald. There was a gap of eight years before Olwyn’s birth. Ted was the youngest.

Farrar was a distinguished name, woven into the historical and spiritual fabric of English poetry. Edith’s family traced their ancestry back to a certain William de Ferrers, who fought in the Battle of Hastings as William the Conqueror’s Master of Horse. Later generations of Farrars became famous in Tudor and Stuart times. One of Ted’s most prominent early poems was ‘The Martyrdom of Bishop Farrar’, telling of how his ancestor was ‘Burned by Bloody Mary’s men at Caermarthen’. It was a poem of fire and smoke, evocative of the tradition of Protestant brimstone sermons that still lived in the Mount Zion Primitive Methodist Chapel over the road. ‘If I flinch from the pain of the burning,’ said the bishop on being chained to the stake, ‘believe not the doctrine that I have preached.’21 A Stoic gene to prepare Ted for his travails?

Nicholas Farrar (1592–1637), a collateral descendant of the martyred bishop, was a scholar, courtier, businessman and religious thinker. In his own way, Ted Hughes would grow up to be all these things. Cambridge University was the making of Nicholas, but he also owed a debt to the New World in that his family was closely involved with the colonial projects of the Virginia Company. The seventeenth-century Farrars eventually settled in the rundown village of Little Gidding, not far from Cambridge, where they established a community of faith and contemplation. It was to Farrar that fellow-Cambridge poet George Herbert sent the manuscript of his poetry collection The Temple from his deathbed with the instruction that it should be either burnt or published. Farrar saw that it was published, with the result that Herbert’s incomparably honest poetry of self-examination has remained in print ever since. As Hughes grew up, learning of his Farrar heritage, he could not have dreamed that a day would come when he too would be entrusted with seeing into print another poetry collection prepared at the moment of death, this one called Ariel. Like his Farrar ancestor, he had the responsibility of saving a loved one’s confessional poetry for posterity. Decisions as to whether to burn or preserve literary manuscripts would trouble him throughout his adult life.

What he did come to know, as he began reading in the canon of English poetry as a teenager, was that T. S. Eliot, the most revered of living poets, took deep religious solace from the example of the Farrar family: his great wartime meditation on the cleansing fire of faith, his fourth Quartet, was called ‘Little Gidding’. Eliot’s language seeps into Hughes’s own metaphysical lyric on his ancestor, ‘Nicholas Ferrer’ (Edith and her children were inconsistent in their spelling of the historic family name). Famously, in ‘Little Gidding’ Eliot began with spring in midwinter and ended with an epiphany of divine fire in the remote chapel deep in the English countryside. There is a catch of deep emotion in Hughes’s voice as he speaks this phrase in his recorded reading of Eliot’s poem. His own poem ‘Nicholas Ferrer’ is located in that same Little Gidding chapel, now ‘oozing manure mud’. The speaker tracks Eliot’s footsteps, past the same pigsty, in the same winter slant light. An ‘estranged sun’ echoes Eliot’s ‘brief sun’ that flames the ice on what in retrospect seem very Hughesian ponds and ditches. Nicholas and his family had ‘Englished for Elizabeth’ but in Hughes’s desolate modern November ‘the fire of God / Is under the shut heart, under the grave sod’.22

Hughes’s poem makes the death of Nicholas Farrar into a turning point in English history. It invokes the desecrating maw of Oliver Cromwell. The Little Gidding community was broken up by Puritans, who saw vestiges of Romish monasticism in their practices. Nicholas’s books were burnt. For Hughes, influenced by the Anglo-Catholic Eliot’s idea of a ‘dissociation of sensibility’ that fractured English culture and poetry at the time of the Civil War, Puritanism was the great enemy of those ‘ancient occult loyalties’ to a deeper, mysterious world that were embodied by such superstitions as astrology.

Ted’s belief in a world beyond the normal came from his mother. Edith Farrar felt that the spirit world was in touch with her. Ever since childhood, she had often felt the sensation of a ghostly hand. One night in June 1944 she was woken by an ache in her shoulder. She got up and saw crosses flashing in the sky above St George’s Chapel, which was across the road from their Mexborough home. She tried to wake William (whom she called Billie) to tell him that a terrible battle was going on somewhere and that thousands of boys were being killed. The next day the radio announced that the D-Day landings had begun early that morning.23 Later, when she and her husband moved to the Beacon, she saw a shadow in the house. She learned that the previous owners had died and their daughter had sold the house and moved into Hebden Bridge. She told the shadow, who was the mother, where her daughter now lived. It never reappeared.24

Mr Farrar, from Hebden Bridge, was a power-loom ‘tackler’ – a supervisor, with responsibility for tackling mechanical problems with the looms. Tall and quiet, with black hair and a heavy black moustache, he was fond of reading, played the violin a little and had a gift for mending watches. His grandson Ted would be good with his hands. Grandma Farrar, Annie, was a farmer’s daughter from Hathershelf, ‘short and handsome with a deep voice and great vitality’. When they went to the local Wesleyan chapel, ‘tears would roll down her cheeks under the veil she wore with her best hat’, so moved was she by the sermon or the hymns. As well as regular chapel attendance, there were prayer meetings once a week in the evening. But on Sunday afternoons came the freedom of country walks and picnics at picturesque Hardcastle Crags. The Farrars had eight children, the eldest born in 1891, the youngest in 1908: Thomas, Walter, Miriam, Edith, Lily, Albert, Horace (who died as a baby) and Hilda. In May 1905, Lily died of pneumonia, aged just four and a half.

As she grew up, Edith got on especially well with Walter, who was both easygoing and strong-willed. He wasn’t good at getting up in the morning. Soon he started work in the clothing trade, while taking evening classes to improve himself. Miriam and Edith left school at thirteen and went into the same trade, training to be machinists making corduroy trousers and moleskin jackets. Miriam was delicate. In June 1916, she caught cold and it turned to pneumonia and she died, aged nineteen.25

This was in the middle of the Great War. Walter had joined up by this time, along with some of the Church Lads Brigade. The whole village turned out to see them off, singing ‘Fight the good fight’ and ‘God be with you till we meet again’. Just weeks after Miriam’s death back home, Walter was wounded at High Wood on the Somme. He returned with a shattered leg that troubled him for the rest of his days. But it could have been worse: at first, he was reported killed in battle, only for the family to receive his Field Card saying ‘I am wounded.’ Mrs Farrar shouted up the stairs, ‘Get up all of you. He’s alive! Alive alive!’ Tom, who was in the Royal Engineers, came back gassed, broken by the death of many of his dearest friends.

Edith and her friends collected eggs and books to take to the wounded, the gassed and the shell-shocked in hospital. On the drizzly morning of 11 November 1918, she was working on army clothing when a male colleague tapped on the window, said, ‘War’s over,’ and threw his cap in the air. A flag was hoisted over the factory and everybody was allowed home, but there was no rejoicing, only deep thankfulness that it was finally over. Thirty thousand local men had joined the Lancashire Fusiliers. Over 13,500 of them were killed.

Years later, Ted Hughes would write ‘you could not fail to realize that the cataclysm had happened – to the population (in the First World War, where a single bad ten minutes in No Man’s Land would wipe out a street or even a village), to the industry (the shift to the East in textile manufacture), and to the Methodism (the new age)’. As he grew up in Mytholmroyd in the Thirties, looking around him and hearing his family tell their stories, it dawned on him that he was living ‘among the survivors, in the remains’.26

Edith’s one joy at the end of the Great War was that Billie Hughes was safe. He was a Gallipoli survivor. The story went that he had been saved from a bullet by the paybook in his breast pocket. Edith first met him in 1916 when he was home on leave, having just won the Distinguished Conduct Medal but then broken his ankle playing football when resting behind the lines – he was always a great footballer, could have been a professional. After the war, they spent their courtship walking the hills and moors, and once a week went to a dance club. In 1920, they discovered that she was pregnant and they married on a pouring wet day. For two shillings and ninepence a week they rented a cottage in Charlestown, to the west of Hebden Bridge. It had a living room, kitchen, two bedrooms and an outside toilet. They scraped together the money for a suite of furniture and on their wedding day Mrs Farrar gave them a carpet and a sewing machine. Billie’s mother was radiant on the wedding day, her white hair and fair skin set off by a mauve hat and veil.

Gerald’s birth was traumatic. The newborn boy lay blue and stiff on the washstand, and the nurse cried, ‘The baby is dead – fetch the doctor.’ But Edith told her to shake and smack him, and before they knew it he was crying and the doctor arrived and said he would be fine. When he was two, Edith went back to work and young Gerald was looked after by Granny Hughes.

They were happy in their little cottage on the hillside above the railway, though Edith didn’t like it when Billie went off for away football matches and did not return until very late at night. In 1927, they moved to Mytholmroyd, the other side of Hebden Bridge, buying the house in Aspinall Street. Now the Hughes family was truly among the Farrars: Uncle Albert, married to Minnie, was down the road at number 19 and Edith’s mother, with teenage Hilda, just round the corner in Albert Street.

The other brothers were doing very well for themselves. In the year of Gerald’s birth Uncle Walter, in partnership with a man called John Sutcliffe, started a clothing factory. When Sutcliffe left, Uncle Tom took over from him. Edith went to work for them. Walter marked and sometimes cut the cloth. He was very good at laying the heavy leather patterns for the trousers, then cutting out from the great long rolls of cloth. He was, his sister saw, ‘the director in every sense of the word’. Tom was more subdued, still affected by the gas of the trenches; Edith was terrified that his mind would drift, costing him a finger on one of the great flashing blades of the cutting machines. He was often to be found sitting in the office next to his little sister Hilda, who did the paperwork.

It was not easy for Edith and Billie to see Tom and Walter in their detached houses on the outskirts of the village: Walter and his wife Alice at Southfield, a handsome villa set back from the Burnley Road, Tom and his wife Ivy at Throstle Bower, at the top of Foster Brook, up towards the moors. Having a house with a name instead of a number was a mark of upward mobility. In addition, the brothers had cars, the ultimate sign of affluence. None of the family liked Ivy Greenwood, who looked down on the Farrars, would not even acknowledge them and certainly never deigned to invite them up to her big house. Olwyn thinks that Ivy was jealous of the close family bond among the Farrars.

The brother who really struggled was Albert. Minnie was regarded as a good catch, but she pushed him hard, resentful that Tom and Walt were getting rich on the factory, while they couldn’t keep up. Albert was a carpenter, like Billie Hughes. They both got work making prefabricated buildings. Albert would make wooden toys, to give to his nephews and nieces, or to sell: ‘toy ducks / On wooden wheels, that went with clicks’.27 One day he was knocked off his bike on the way to work and he was never the same after that.

Like all the Farrar children, Hilda left school at thirteen, but she took evening classes, learned shorthand, typing and bookkeeping, enabling her to become company secretary for her brothers. She married a much older man called Victor Bottomley, who had something to do with the motor trade. He turned out to be ‘a wrong ’un’,28 and before long Annie Farrar was instructing her sons Tom and Walt to go and bring Hilda home, where she stayed with Minnie and Albert at 19 Aspinall Street (eventually Hilda and Grandma settled at number 13).

Walt had his sadness. His two elder children, Barbara and Edwin, were, as their cousin Vicky put it, ‘witless’. Barbara seemed conscious that something was wrong with her as she struggled to learn to read. Edwin was in his own closed world. James, the only ‘normal’ son, died at the age of eleven.

When Gerald left school, he too went to work at Sutcliffe Farrar, which was located just beyond the Zion chapel. When the slump came in the early Thirties, men and women were laid off, or reduced to working two or three days a week. Billie had been working for his brothers-in-law but he was put on short time too, and in 1936 he got fed up, gave in his notice and went off with a friend to do building work for the government in South Wales. With no work at the factory, Gerald had taken to roaming the moors, leaving Edith miserable and alone with Olwyn and Ted, both under ten. She worked a little at the factory, sewing hooks and eyes on flannel trousers, and they had enough money to get by. They had paid off the house by then, food was reasonably cheap and Edith’s sewing skills meant that clothes could be mended. Billie came home once a month and soon realised how much he was missing the children. They had come into a little money from Granny Hughes and with many people struggling through the Great Depression there were opportunities in small business. Billie decided he wanted a newsagent’s. Eventually, they found one that was suitable. There was only one problem: it was 50 miles to the south-east, near Doncaster, in a ‘dark dirty place’29 called Mexborough.

They all went down in the removal van. When they arrived, Billie stood behind the counter of the new shop and the family walked in, trying to look confident. Then they went out and helped with the furniture. When the van left, Gerald sat down and cried.

2

Capturing Animals (#ulink_dea48d1f-1065-5f4a-9935-1d56d90746a5)

Dumpy, bustling Moira Doolan was a powerhouse of ideas at the BBC in the early Sixties.1 Middle-aged and unmarried, she spoke with an Irish lilt and was passionate about her work as Head of Schools Broadcasting. In January 1961 Ted Hughes wrote to her with an idea for a radio series. She invited him to lunch and they worked up his proposal. It eventually became Listening and Writing, a sequence of ten talks for the Home Service’s daytime schools programming, broadcast between October 1961 and May 1964.2 Nine of the ten, together with illustrative poems by Hughes and others, were published in a book, aimed at teachers and dedicated to his own English teachers, Pauline Mayne and John Edward Fisher. Entitled Poetry in the Making, it became a classroom vade mecum for a generation and indeed one of Hughes’s bestselling books.3

In a brief introduction, he described the talks as the notes of a ‘provisional teacher’ and of his belief in the immeasurable ‘latent talent for self-expression’ in every child. The teacher’s watchword should be for children – he was typically thinking of pupils between the ages of ten and fourteen – to write in such a way that they said what they really meant. With self-expression comes self-knowledge and ‘perhaps, in one form or another, grace’.4

The series started from autobiography. The first talk, entitled ‘Capturing Animals’, began: ‘There are all sorts of ways of capturing animals and birds and fish. I spent most of my time, up to the age of fifteen or so, trying out many of these ways, and when my enthusiasm began to wane, as it did gradually, I started to write poems.’5 When the harvest was gathered in, little Ted would snatch mice from under the sheaves and put them in his pocket, more and more of them, until there were thirty or forty crawling around in the lining of his coat. He came to think that this was what poems were like: experiences captured and kept about the person.

He then explained that his earliest memory was of being three, placing little lead animals all the way round the fender of the fire in the front room, nose to tail. There was no greater treat than a trip to Halifax, where his mother or Aunt Hilda would buy him one of these creatures from Woolworth’s. Then for his fourth birthday Hilda gave him a thick green-backed book about animals. He pored over it, read the descriptions over and over again, drew copies of the photographs of animals and birds. Sometimes he would place the lead figures on the fender and read their descriptions from the book: the words put together with the things, the poet in the making. When he discovered plasticine, the possibilities for his personal menagerie became infinite, bounded only by the limit of his huge imagination.

He confided to his listeners that his passion for wildlife came from his elder brother. Gerald was his hero. And his saviour. One Christmas Billie Hughes bought his boys a Hornby clockwork train set. It was laid out in the front room by the piano. Three-year-old Ted loaded his lead soldiers aboard and Gerald wound up the engine. But an excited Ted tripped on the fender and fell towards the fire. Gerald scooped him out, but not before his hands had been blistered. ‘Fires can get up and bite you,’ Ted would say in later years.6

But this is Gerald’s memory. Olwyn’s earliest recollections are of trotting out into the fields with her mother and baby Ted, then of Ted’s two close friends, Derek Robertshaw and Brian Seymour, coming round every Saturday morning while the Hugheses were having breakfast, planning with Ted where they would go for the day and what animals they would find. They lived in the fields and they were never bored. As Olwyn remembered it, Gerald was always off with friends his own age. In Ted’s adult writings, the bond between the two brothers has a mythic force which exaggerates their closeness.

It was just before his fifth birthday that he joined Gerald on a camping trip for the first time. They were to spend the night up by the stream in the woods known as Foster Clough. Edith told Gerald not to let Ted take his model boat, for fear that he would sail it in the stream and get soaked. Those two friends, Derek and Brian, came round with advice, then the brothers set off, stopping on the way to buy sweets from the shop just past Uncle Walt’s factory. Watched by some very interested cows, they set up their tent and made a fire in a little clearing, fenced off with wire to keep the cattle out of the wood. Just before midnight, they heard their father’s call. He had come to check on them and was taking Ted home because there was a bull among the cows, making them too frisky for comfort. Ted was very excited by the bull.

From then on, Ted would often accompany Gerald on to the moor. He scurried silently beside his brother, pretending to be a Red Indian hunter. He kept a tom-tom drum hidden in Redacre Wood, where, according to local lore, an Ancient Briton, buried spirit of land and nation, lay beneath a half-ton rock.7 They loved the silence of the hills, shrouded in morning mist as they looked out over the valley below. They flew gliders and kites. Gerald taught Ted to identify all the different birds. The younger brother was fascinated by hawks and owls. Gerald shot rats, wood pigeon, rabbits and the occasional stoat, Ted acting as his retriever. Sometimes Gerald would let him have a go with the air rifle. Once the slug ricocheted back and gave him a bloody forehead, but they managed to keep the accident from their parents. They met an old-school gamekeeper called McKinley who regaled them with stories and sometimes paid them a shilling for a fat rabbit. They fished in the canal, using nets made from old curtains.

They poked around the site of a crashed plane – an RAF bomber on a training exercise had run into fog over Mytholmroyd – and salvaged bits of tubing for their own model planes. On the same site, they unearthed dozens of old lead bullets: it had been a firing range in the Great War.

In winter they sledged all the way down the fields above Jubilee Street. On snowy nights, they opened the skylight and listened to the shunting engines strain at the frozen trucks in the sidings. In summer, they would help out their uncles in the allotment or play tip cat in the fields with Uncle Albert – this was a game in which you balanced a block of wood on the end of a bat, then whacked it as far as you could send it. Occasionally, there was a special treat: a trip to the seaside, a first sight of big cats at Blackpool Zoo.

Olwyn did not join them on the hills, but she was there for family picnics at Hardcastle Crags and dips in the rocky pool on Cragg Vale. Mrs Hughes (‘Mam’ to Gerald, ‘Ma’ to Olwyn and Ted) was a great walker and swimmer. The children’s love of nature came from her. They all shared in the peace and magic of Redacre Wood, which seemed like their own private paradise.

The three siblings played in the open air around the Zion chapel. They stole gooseberries from a lady’s garden up on the Banks. They gave a fright to a younger boy called Donald Crossley by tying him to a tree, spreading leaves around his feet and setting fire to them as they danced and whooped like Red Indians.

Time spent indoors meant model-making with Gerald or reading with bookish Olwyn. Ma wrote poems for them and made up tales. They all loved the one about Geraldine mouse, Olwyna mouse and Edwina mouse because it echoed their own adventures. Grandma Farrar was charmed when they went round and read her the words of Edward Thomas, the poet and countryman who had died in the war. It was Edith who also instilled a passion for poetry in Olwyn and Ted. Wordsworth was her favourite, as might be expected of a woman who loved walking and the beauties of nature.

The war haunted Ted and his father because it had decimated a generation of the Calder Valley’s young men. The sorrow in the air of the valley came more from the war than from the decline of industry.

Gerald’s earliest memory was of finding his father’s sergeant’s stripes in a drawer and wondering what they were. Billie Hughes brought two other relics back from the war: his Distinguished Conduct Medal and the shrapnel-peppered paybook that had been in his breast pocket at Gallipoli. He told the family that he was one of only seventeen men from the company to have survived. Olwyn had a pearl necklace, which she loved to play with. Her father explained that it had been taken from the body of a dead Turk. He would occasionally shout at night in his sleep, dreaming of the Turks charging towards his trench.

When Ted was four and Olwyn six, for half a year every Sunday morning their father stayed in bed and they came in with him and said, ‘Tell us about the war.’ He told them everything, in the goriest detail, including things not very suitable for a four-year-old boy. Dismembered bodies, arms sticking out of the mud. Ted either suppressed or forgot all this, later saying that his father never talked about the war. When he wrote his story ‘The Wound’ he told Olwyn that it was something he had dreamed. The moment he woke up, he wrote it down. But he forgot certain details, so he went back to sleep and dreamed it again, filling in the gaps. But Olwyn thought that part of it was taken from their father’s memories of the war. The story includes a long walk to a palace: this was his father going up to the Front on the way to a particular sortie in which he, as Sergeant-Major, led a small group of men in a successful assault on a German machine-gun post. It was this walk up the line that Billie described so vividly in bed. He also talked about his time in the Dardanelles, but that mainly consisted of drinking tea and picking lice off his uniform. The Western Front was much more dramatic.8

Ted was formed by his outdoor life and his books, by his mother’s stories and father’s memories, but he was an attentive schoolboy at the Burnley Road Council School, bright, always asking questions. The headmaster gave a fearsome talk on the evils of alcohol. The message stuck. Ted grew up to love good wine, but always held his drink and never became addicted. Many writers have become alcoholics without bearing anguish remotely comparable to his.

A memory that became a foundational myth. In his fifties, Ted told his schoolfriend Donald Crossley that it was in Crimsworth Dene, camping under a little cliff on a patch of level ground beside what later became a council stone dump, that he had the dream that turned later into all his writing. It was a sacred place for him.9

It was sacred to Gerald as well: he told Donald that the memory of Crimsworth Dene sustained him through his service in the desert war. This secret valley, just north of Hebden Bridge, became in memory the spiritual home of the brothers.10 Gerald remembered how they had pitched their two-man Bukta Wanderlust tent for the last time. Two days later the family moved to Mexborough and life was never the same again. He felt that they both spent the rest of their lives trying to recapture those early days in the happy valley, but they never did.

The site was recommended by Uncle Walter. It had been a favourite camping spot for him, Uncle Tom and their friends before the Great War. At the top of the valley, there was a pool and a waterfall, with an old packhorse bridge going over. This had long been a favoured picnicking place for locals. The Hughes family cherished an old photo taken there: it showed six young men in Sunday best, before the war.

There was a drystone wall along the slope above the clearing where the boys pitched their tent. On their second day, they found a dead fox there. It had been killed by a deadfall trap – a heavy rock or slab tilted at an angle and held up with a stick that when dislodged causes the slab to fall, crushing the animal beneath. That night Ted slept restlessly in the tent. He told Gerald of ‘a vivid dream about an old lady and a fox cub that had been orphaned by the trap’.11

This was the dream that, according to Ted’s letter to Donald Crossley nearly fifty years later, turned into all his writing. It was his first thought-fox. He told the tale himself in ‘The Deadfall’, a short story from the last decade of his life, written for a collection of ghost stories, published to celebrate the centenary of the National Trust and edited by one of his closest friends, the children’s novelist Michael Morpurgo.12 All the stories are set in houses or landscapes owned by the Trust, of which Crimsworth Dene was one.

In the story, it is Ted’s first time in the secret valley, with its steep sides and overhanging woods. He immediately senses that it is the most magical place he has ever been to. The enclosed space means that every note of the thrush echoes through the valley and he feels compelled to speak in a whisper. At night, he can’t stop thinking about the fox for which the trap has been set. The idea of the creature near by, in its den, ‘maybe smelling our bacon’, makes the place more mysterious than ever. On the second night he is woken by the dream of the old lady, calling him out of the tent. He follows her voice up the slope to the trap, where he finds a young fox, still alive but with tail and hind leg caught beneath the great slab of stone. He is choked by ‘the overpowering smell of frightened fox’. He realises that the woman has brought him to the cub, wants him to free it. She has not gone to Gerald, because she knows that he would be likely to kill it. Summoning all his strength he manages to lift the corner of the slab – the cub snarling and hissing at him like a cat – just enough to set the animal free. It runs away and the old lady vanishes. But when he looks back at the deadfall there is something beneath it. At this moment, his brother wakes and calls him back to bed. It rains. In the morning, they go up to the deadfall and there is a big red fox, the bait (a dead wood pigeon) in its mouth.

According to the story, Gerald then digs a grave for the fox. As Ted helps him push the loose soil away, he feels what seems to be a knobbly pebble. When he looks at it closely, it turns out to be a little ivory fox, about an inch and a half long, ‘most likely an Eskimo carving’. He treasures it all his days. He and Gerald conclude that the old lady in the dream was the ghost of the dead fox.

Hughes admits in the preface to his collected short stories that this version of the incident, prepared for Morpurgo’s ghost collection, has ‘a few adjustments to what I remember’. In Gerald’s account, Ted’s dream of the old lady comes the night after they have discovered the body, whereas in the story it is a premonition of the fox’s death. Ted insisted on the reality of the memory, yet neither Gerald nor Olwyn has any recollection of the ivory fox.13 It was only as an adult that Ted began collecting netsuke and Eskimo carvings of animals.

‘The Deadfall’ was the only short story of his later career. He had not written one for fifteen years. Morpurgo’s invitation was an irresistible opportunity to round off his work in the genre. He gathered it together with his earlier stories and made it what he called the ‘overture’ to his writing.14 The camping trip with Gerald in Crimsworth Dene, the dream of the freed fox and the ivory figure that symbolically transformed his lead animal toys into tokens of art came together as his retrospective narrative of creative beginning.

The radio talks for schools that were eventually published as Poetry in the Making give incomparable insight into Ted Hughes, poet in the making. As the boy Ted sculpted his plasticine animals, so the adult writer created poetic images of fox, bird and big cat. In the same way, Ted the teacher found the right voice to capture the attention of ten- to fourteen-year-olds – exactly as his own attention had been caught by Miss Mayne and Mr Fisher.

Early in the second talk, called ‘Wind and Weather’ (there was no shortage of either in the Calder Valley), he suggested that the best work of the best poets is written out of ‘some especially affecting and individual experience’. Often, because of something in their nature, poets sense the same experience happening again and again. It was like that for him with his dreams, his premonitions and his foxes. A poet can, he argues, achieve greatness through variation on the theme of ‘quite a limited and peculiar experience’: ‘Wordsworth’s greatest poetry seems to be rooted in two or three rather similar experiences he had as a boy among the Cumberland mountains.’15 Here Wordsworth stands in for the speaker himself: the deadfall trap in Crimsworth Dene was Ted Hughes’s equivalent of what Wordsworth called those ‘spots of time’ that, ‘taking their date / From our first childhood’, renovate us, nourish and repair our minds with poetry.16

At school, Ted was plagued with the idea that he had much better thoughts than he could ever get into words. He couldn’t find the words, or the thoughts were ‘too deep or too complicated for words’. How to capture those elusive, deep thoughts? He found the answer, he tells his schools audience in the talk called ‘Learning to Think’, not in the classroom but when fishing. Keeping still, staring at the float for hours on end: in such forms of meditation, all distractions and nagging doubts disappear. In concentrating upon that tiny point, he found a kind of bliss. He then applied this art of mindfulness to the act of writing. The fish that took the bait were those very thoughts that he had previously been unable to get into words. This mental fishing was the process of ‘raid, or persuasion, or ambush, or dogged hunting, or surrender’ that released what he called the ‘inner life’ – ‘which is the world of final reality, the world of memory, emotion, imagination, intelligence, and natural common sense’.17

Though a fisherman all his life, Ted did not follow in Gerald’s footsteps as a hunter, despite being an excellent shot. To judge from his sinister short story ‘The Head’, in which a brother’s orgiastic killing of animals leads to him being hunted down himself, he was distinctly ambivalent about Gerald’s obsessive hunting.18 At the age of fifteen, Ted accused himself of disturbing the lives of animals. He began to look at them from their own point of view. That was when he started writing poems instead of killing creatures. He didn’t begin with animal poems, but he recognised the analogy between poetry-writing and capturing animals: first the stirring that brings a peculiar thrill as you are frozen in concentration, then the emergence of ‘the outline, the mass and colour and clean final form of it, the unique living reality of it in the midst of the general lifelessness’.19 To create a poem was as if to hunt out a new species, to bring not a death but a new life outside one’s own.

Like an animal, a living poem depends on its senses: words that live, Hughes insists, are those that belong directly to the senses or to the body’s musculature. We can taste the word ‘vinegar’, touch ‘prickle’, smell ‘tar’ or ‘onion’. ‘Flick’ and ‘balance’ seem to use their muscles. ‘Tar’ doesn’t only smell: it is sticky to touch and moves like a beautiful black snake. Truly poetic words belong to all the senses at once, and to the body. Find the right word for the occasion and you will create a living poem. It is as if there is a sprite, a goblin, in the word, ‘which is its life and its poetry, and it is this goblin which the poet has to have under control’.20

Poetry is made by capturing essences: of a landscape, a person, a creature. In one talk, Hughes suggests that ‘beauty spots’ – he was remembering his childhood places such as Hardcastle Crags and the view from the moors above Mytholmroyd – ease the mind because they reconnect us to the world in which our ancestors lived for 150 million years before the advent of civilisation (the number of years is a typical Ted exaggeration). Poignantly, given that the broadcast went out a year after her death, the example he quoted at the close of this talk was ‘a description of walking on the moors above Wuthering Heights, in West Yorkshire, towards nightfall’ – ‘by the American poet, Sylvia Plath’.21

To capture people, you must find a memorable detail. ‘An uncle of mine was a carpenter, and always making curious little toys and ornaments out of wood.’ This memory of Uncle Albert was all that was needed to create the character of ‘Uncle Dan’ in his children’s poetry collection Meet My Folks!: ‘He could make a helicopter out of string and beetle tops / Or any really useful thing you can’t get in the shops.’22 To invent a good poem, though, you shouldn’t just transcribe your memories. You need to rearrange your relatives in imagination. ‘Brother Bert’ in Meet My Folks!, who keeps in his bedroom a menagerie of every bizarre creature from Aardvark to Platypus to Bandicoot to ‘Jungle-Cattypus’, is an exaggerated version of Gerald (who never kept anything bigger than a hedgehog). But the line ‘He used to go to school with a Mouse in his shirt’, Hughes reassures his listeners, does not refer to Gerald: ‘Somebody else did that.’23 The somebody else was Ted. In the poem, he and Gerald have become one. It was a way of registering his affection for his brother. His feelings about his mother, he admits, were too deep and complicated to capture: she is the one absence from the feast of Meet My Folks!

Think yourself into the moment. Touch, smell and listen to the thing you are writing about. Turn yourself into it. Then you will have it. That, for Hughes, was the essence of poetry.

He ended that seminal opening talk ‘Capturing Animals’ with two personal examples. Late one snowy night in dreary lodgings in London, having suffered from writer’s block for a year, he had an idea. He concentrated very hard and within a few minutes he had written his first ‘animal’ poem. It is about a fox but it is also about itself. The thought, the fox and the poem are one. In the ‘midnight moment’s forest’, something is alive beside the solitary poet. He captures the movement, the scent, the bright eyes. The fox’s paw print becomes the writing on the page. ‘Brilliantly, concentratedly … The page is printed’: it is a captured animal.24

The second example was one of his ‘prize catches’: a pike in a pool at Mexborough.

3

Tarka, Rain Horse, Pike (#ulink_c93ff547-7dbd-5190-9679-58d46bf4b0c1)

They moved on 13 September 1938, four weeks after Ted’s eighth birthday. They would stay for thirteen years to the day.1 Olwyn cried for a fortnight and the cat moped beneath a bed upstairs. Ted seemed least affected by the move. He was always adaptable, ready for a new direction. He was immediately enrolled at the Schofield Street Junior School round the corner, getting to know the local boys, some of them shopkeepers’ children, which is what he now was. His best mate was a lad called Swift, mother a greengrocer, father a miner. A neighbouring family had a brutal father, a miner who came home drunk, his face blackened from work. Ted befriended the redheaded daughter Brenda. On Saturday mornings he went to the local ‘flea pit’ cinema and watched Westerns.

The family’s new address was 75 Main Street, Mexborough: a newsagent’s in the centre of a busy mining town, where the bestselling paper was the Sporting Life, to be read daily before placing a bet on the horses. You went into the shop and diagonally to the right was a door to the downstairs living room. Edith and Billie had the front bedroom over the shop. Then there was a big bedroom to the right, over the living room. This had a double and a single bed. A door from here led to a smaller room over the kitchen. Beyond that, there was a room with just a bath. The loo was downstairs and outside. Ted played with his train set in the big bedroom. There was a garage behind, where Ted began keeping animals, notably rabbits and guinea pigs. He cried inconsolably when they died. It was not unknown for him to keep a hedgehog under the sofa in the living room.

Once again, they were overshadowed by a church: across the road stood the ugly red-brick edifice of the St George the Martyr Chapel of Ease to St John the Baptist Parish Church. Its clock had a loud tuneless chime. This was where, six years later, Edith would look out before dawn on D-Day and see crosses in the sky. It was within weeks of their moving to Mexborough that Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain returned from his meeting with Hitler in Munich and was heard on the radio speaking of ‘peace for our time’.

The business went well. Billie ordered the magazines and the tobacco, and organised the paper rounds. He also took on a concession selling tickets for coach trips. Edith diversified the stock, ordering games, stationery and dress patterns. Gerald and Ted became paperboys. Ted read all the comics and boys’ magazines on the shelves before they were sold. Even his mature poetry would be shot through with a love of super-heroes and an element of zap, kerpow and kaboom.

In later years, Aunt Hilda and Cousin Vicky came down at Christmas. For the children, the whole shop was their Christmas present: each received a pillowcase stuffed with goods, toys, sweets, chocolate.

Gerald struggled to find work locally. He had a brief stint at a steelworks just outside Rotherham, but this was ended by an accident. Then he moved down to Barnet, just north of London, to train as a garage mechanic. He bought a motorbike and started roaring around the countryside, to the consternation of young Ted, who told him he should stick to pedal power. But Gerald’s heart remained in the fields. His favoured reading was the Gamekeeper magazine and it was in answer to an advertisement there that he got a seasonal job as a second keeper on an estate in Devon. This involved rearing pheasants and locating them in the right places to be shot when the 1939 season opened. It was in Devon that he heard Prime Minister Chamberlain on the radio once again, this time announcing that the country was at war with Germany.

The war brought painful memories for Billie and Edith. For Gerald, it began a new life. He returned home at the end of the shooting season, remained there through the ‘phoney war’ and joined up in the summer of 1940. His skill with his hands and experience with engines meant that he was well suited for aircraft repair and maintenance in the RAF. From 1942 to 1944 he was posted to the desert war in North Africa. Gerald’s absence meant that Olwyn and Ted clung close together, sometimes sharing a bed. One of his earliest unpublished poems, witty and affectionate, is called ‘For Olwyn Each Evening’.2