Полная версия:

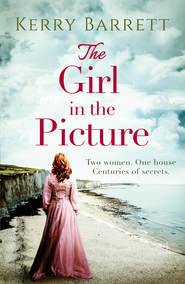

The Girl in the Picture

Two women. One house. Centuries of secrets.

East Sussex Coast, 1855

Violet Hargreaves is the lonely daughter of a widowed industrialist, and an aspiring Pre-Raphaelite painter. One day, the naïve eighteen-year-old meets Edwin; a mysterious and handsome man on the beach, who promises her a world beyond the small costal village she’s trapped in. But after ignoring warning about Edwin, a chain of terrible events begins to unfold for Violet…

East Sussex Coast, 2016

For thriller-writer Ella Daniels, the house on the cliff is the perfect place to overcome writer’s block, where she decides to move with her small family. But there’s a strange atmosphere that settles once they move in – and rumours of historical murders next door begin to emerge. One night, Ella uncovers a portrait of a beautiful young girl named Violet Hargreaves, who went missing at the same time as the horrific crimes, and Ella becomes determined to find out what happened there 160 years ago. And in trying to lay Violet’s ghost to rest, Ella must face ghosts of her own…

This haunting timeslip tale is perfect for fans of Kate Riordan, Tracy Rees, Kate Morton and Lucinda Riley.

The Girl in the Picture

Kerry Barrett

ONE PLACE. MANY STORIES

Copyright

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2017

Copyright © Kerry Barrett 2017

Kerry Barrett asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

eBook Edition © September 2017 ISBN: 9780008221577

Version: 2018-01-23

Contents

Cover

Blurb

Title Page

Author Bio

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Excerpt

Endpages

Copyright

KERRY BARRETT

was a bookworm from a very early age and did a degree in English Literature, then trained as a journalist, writing about everything from pub grub to EastEnders. Her first novel, Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered, took six years to finish and was mostly written in longhand on her commute to work, giving her a very good reason to buy beautiful notebooks. Kerry lives in London with her husband and two sons, and Noel Streatfeild’s Ballet Shoes is still her favourite novel.

I owe one big thank you to my lovely friend Becky Knowles. One day, as we strolled round an exhibition of Pre-Raphaelite paintings, she wondered aloud what it would have been like to have been a female artist at the time, and inadvertently gave birth to Violet Hargreaves.

I’d also like to thank my editor Victoria Oundjian for her help and support, and wish her lots of luck in her new role. And, as always, thanks to the team at HQ Digital, my family, friends and all my readers.

Chapter 1

Present day

Ella

‘It’s perfect,’ Ben said. ‘It’s the perfect house for us.’

I smiled at the excitement in his voice.

‘What’s it like?’ I asked. I was in bed because I was getting over a sickness bug but suddenly I felt much better. I sat up against the headboard and looked out of the window into the grey London street. It was threatening to rain and the sky was dark even though it was still the afternoon.

‘I’ll send you some pictures,’ Ben said. ‘You’ll love it. Sea view, of course, quiet but not isolated …’ He paused. ‘And …’ He made an odd noise that I thought was supposed to be a trumpet fanfare.

‘What?’ I said, giggling. ‘What else does it have?’

Ben was triumphant. ‘Only a room in the attic.’

‘No,’ I said in delight. ‘No way. So it could be a study?’

‘Yes way,’ said Ben. ‘See? It’s made for us.’

I glanced over at my laptop, balanced on the edge of my dressing table that doubled as a desk, which in turn was squeezed into the corner of our bedroom. We’d been happy here in this poky terraced house. Our boys had been born here. It was safe here. But this was a new adventure for us, no matter how terrifying I found the thought. And just imagine the luxury of having space to write. I looked at my notes for my next book, which were scattered over the floor, and smiled to myself.

‘What do the boys think?’ I asked.

‘They’re asleep,’ Ben said. ‘It’s pissing down with rain and we’re all in the car. I rang the estate agent and he’s on his way, so I’ll wake the boys up in a minute.’

‘Ring me back when he arrives,’ I said. ‘FaceTime me, in fact. I want to see the house when you do.’

‘Okay,’ Ben said. ‘Shouldn’t be long.’

I ended the call and leaned back against my pillow. I was definitely beginning to feel much better now and I’d not thrown up for a few hours, but I was glad I’d not gone down to Sussex with Ben because I was still a bit queasy.

I picked up my glass of water from the bedside table and held it against my hot forehead while I thought about the house. It had been back in the spring when we’d spotted it, on a spontaneous weekend away. Ben had a job interview at a football club in Brighton. Not just any job interview. THE job interview. His dream role as chief physio for a professional sports team – the job he’d been working towards since he qualified. Great money, amazing opportunities.

The boys and I had gone along with him at the last minute and while Ben was at the interview, I’d wandered the narrow lanes of Brighton with Stanley in his buggy and Oscar scooting along beside me. I had marvelled at the happy families I saw around me and how my mood had lifted when I saw the sea, twinkling in the sunshine at the end of each road I passed. That day I felt like anything was possible, like I should grab every chance of happiness because I knew so well how fleeting it could be.

The next day – after Ben had been offered the job – we’d driven to a secluded beach, a little way along the coast, and sat on the shingle as the boys ran backwards and forwards to the surf.

‘I love it here,’ I said, shifting so I could lie down with my head resting on Ben’s thigh and looking up at the low cliffs that edged the beach. I could see the tops of the village houses that overlooked the sea and, on the cliff top, a slightly skew-whiff To Let sign.

‘I wish we could live here,’ I said, pointing at the sign. ‘Up there. Let’s rent that house.’

Ben squinted at me through the spring sunshine. ‘Yeah, right,’ he said. ‘Isn’t that a bit spontaneous for you?’

I smiled. He was right. I’d never been one for taking risks. I was a planner. A checker. A researcher. I’d never done anything on a whim in my entire life. But suddenly I realized I was serious.

‘I nearly died when Stanley was born,’ I said, sitting up and looking at him. ‘And so did Stanley.’

Ben looked like he was going to be sick. ‘I know, Ella,’ he said gently. ‘I know. But you didn’t – and Stan is here and he’s perfect.’

We both looked at the edge of the sea where Stanley, who was now a sturdy almost-three-year-old, was digging a hole and watching it fill with water.

‘He’s perfect,’ Ben said again.

I took his hand, desperate to get him to understand what I was trying to say. ‘I know you know this,’ I said. ‘But because of what happened to my mum I’ve always been frightened to do anything too risky – I’ve always just gone for the safe option.’

Ben was beginning to look worried. ‘Ella,’ he said. ‘What is this? Where’s it come from?’

‘Listen,’ I said. ‘Just listen. We’ve lived in the same house for ten years. I don’t go on the tube in rush hour. I wouldn’t hire jet skis on our honeymoon. I’m a tax accountant for heaven’s sake. I don’t take any risks. Ever. And suddenly I see that it’s crazy to live that way. Because if life has taught me anything it’s that even when you’re trying to stay safe, bad things happen. I did everything right, when I was pregnant. No booze, no soft cheese – I even stopped having my highlights done although that’s clearly ridiculous. And despite all that, I almost died. Oscar almost lost his mum, just like I lost mine. And you almost lost your wife. And our little Stanley.’

‘So what? Three years later, you’re suddenly a risk taker?’ Ben said.

I grimaced. ‘No,’ I said. ‘Still no jet skis. But I can see that some risks are worth taking.’ I pointed up at the house on the cliff. ‘Like this one.’

‘Really?’ Ben said. I could see he was excited and trying not to show it in case I changed my mind. ‘Wouldn’t you miss London?’

I thought about it. ‘No,’ I said, slowly. ‘I don’t think I would. Brighton’s buzzy enough for when we need a bit of city life, and the rest of the time I’d be happy somewhere where the pace of life is more relaxed.’

I paused. ‘Can we afford for me to give up work?’

‘I reckon so,’ Ben said. ‘My new job pays well, and …’

‘I’ve got my writing,’ I finished for him. Alongside my deathly dull career in tax accountancy, I wrote novels. They were about a private investigator called Tessa Gilroy who did all the exciting, dangerous things I was too frightened to do in my own life. My first one had been a small hit – enough to create a bit of a buzz. My second sold fairly well. And that was it. Since I’d had Stan, I’d barely written anything at all. My deadlines had passed and my editor was getting tetchy.

‘Maybe a change of scenery would help,’ I said, suddenly feeling less desperate when it came to my writing. ‘Maybe leaving work, and leaving London, is just what I need to unblock this writer.’

That was the beginning.

Ben started his job at the football club, commuting down to Sussex every day until we moved, and I handed in my notice at work. Well, it was less a formal handing in of my notice and more a walking out of a meeting, but the result was the same. I was swapping the dull world of tax accountancy for writing. I hoped.

My phone rang again, jolting me out of my memories.

‘Ready?’ Ben said, smiling at me from the screen.

‘I’m nervous,’ I said. ‘What if we hate it?’

‘Then we’ll find something else,’ said Ben. ‘No biggie.’

I heard him talking to another man, I guessed the estate agent, and I chuckled as the boys’ tousled heads darted by.

It wasn’t the best view, of course, on my phone’s tiny screen, but as Ben walked round the house I could see enough to know it was, indeed, perfect. The rooms were big; there was a huge kitchen, a nice garden that led down to the beach where we’d sat all those months before, and a lounge with a stunning view of the sea.

‘Show me upstairs,’ I said, eager to see the attic room.

But the signal was patchy and though I could hear Ben as he climbed the stairs I couldn’t see him any more.

‘Three big bedrooms and a smaller one,’ Ben told me. ‘A slightly old-fashioned bathroom with a very fetching peach suite …’

I made a face, but we were renting – I wasn’t prepared to risk selling our London place until we knew we were settled in Sussex – so I knew I couldn’t be too fussy about the décor.

‘… and upstairs the attic is a bare, white-painted room with built-in cupboards, huge windows overlooking the sea, and stripped floorboards,’ Ben said. ‘It’s perfect for your study.’

I couldn’t speak for a minute – couldn’t believe everything was working out so beautifully.

‘Really?’ I said. ‘My attic study?’

‘Really,’ said Ben.

‘Do the boys like it?’

‘They want to get a dog,’ Ben said.

I laughed with delight. ‘Of course we’ll get a dog,’ I said.

‘They’ve already chosen their bedrooms and they’ve both run round the garden so many times that they’re bound to be asleep as soon as we’re back in the car.’

‘Then do it,’ I said. ‘Sign whatever you have to sign. Let’s do it.’

‘Don’t you want to see the house yourself?’ Ben said carefully. ‘Check out schools. Make sure things are the way you want them?’

Once I would have, but not now. Now I just wanted to move on with our new life.

‘Do you want to talk to your dad?’

‘No.’ I was adamant that wasn’t a good idea because I knew he’d definitely try to talk us out of it. I’d not told him anything about our move yet. He didn’t even know I’d handed in my notice at work – as far as he was aware, Ben was going to stick with commuting and I’d carry on exactly as I’d been doing up until now.

I got my cautious approach to life from my dad and I spent my whole time trying very hard not to do anything he wouldn’t approve of. I’d never had a teenage rebellion, sneaked into a pub under age, or stayed out five minutes past my curfew. I’d chosen my law degree according to his advice – he was a solicitor – and then followed his recommendations for my career.

This move was the nearest I’d ever got to rebelling and I knew Dad would be horrified about me giving up my safe job, about Oscar changing schools, and us renting out our house. And even though moving to Sussex would mean we lived much nearer him, I thought that the less he knew of our plans, the better.

‘We could come down again next weekend,’ Ben was saying. ‘When you’re feeling well?’

‘No,’ I said, making my mind up on the spot. ‘I don’t want to risk losing the house. We were lucky enough that it’s been empty this long, let’s not tempt fate. Sign.’

‘Sure?’ Ben said.

‘I’m sure.’

‘Brilliant,’ he said, and I heard the excitement in his voice again, along with something else – relief perhaps. He would be pleased to leave London.

‘Ella?’

‘Yes?’

‘I’ve been really happy,’ he said softly. ‘Really happy. In London, with you, and the boys. But this is going to be even better. I promise. It’s a leap of faith, and I know it’s scary and I know it’s all a bit spontaneous, but if we’re all together it’ll be fine.’

I felt the sudden threat of tears. ‘Yes,’ I said.

‘We’re strong, you and me,’ Ben said. ‘And Oscar and Stan. This is the right thing for us to do.’

‘I know,’ I said. ‘We’re going to be very happy there.’

Chapter 2

From then I barely had time to draw breath, which was lucky really. If I’d had time to think about what we were doing I’d have changed my mind, because the truth was I was absolutely terrified about the move.

On paper, the house was perfect and I trusted Ben’s judgement. And it wasn’t as if I hadn’t been involved, I told myself, when all my worries about how I’d not even seen our new home surfaced. I’d spotted it first. I’d seen it on FaceTime and on the estate agent’s website. I’d been part of the decision-making from the start.

So, I concentrated on the fact that we’d found a tenant for our London house with almost indecent haste. I worked out whether our battered sofa would fit in the new lounge, and if the boys would need new beds, and I dreamed of having my own study, a haven, tucked away in the attic room.

The one fly in the ointment was Dad. I had to tell him we were moving of course. So one day, a week or so before we finally went and just before I finished work, I took a half-day and drove down to Kent to see him and my step-mum, Barb.

‘I thought we could go for a late lunch at the pub,’ I said when I arrived, thinking that if I told Dad the news in public, it might go better. I breathed a sigh of relief when Barb and Dad agreed, so we all strolled along the road towards their local. Truth be told, I had no idea how Dad would react because I’d never done anything he didn’t agree with before.

‘He might be fine,’ Ben had said. ‘I think you’re overthinking this. He just wants you to be happy.’

But I wasn’t sure. I was scared my whole relationship with my dad was conditional on me doing what he wanted me to do. I knew he would be nervous about the risk we were taking, and he’d expect me to listen to his concerns, and then announce he was right and change my mind. But I wasn’t going to do that this time – and that’s why I was so worried.

I’d grown up, with Dad, in Tunbridge Wells. Dad didn’t live in the same house any more because he and Barb – who I loved to bits – had moved when they got married, soon after I started university. It wasn’t far from where we’d lived when I was a kid, but far enough, if you see what I mean.

‘So how’s Ben’s job going?’ Dad asked, as we settled down at our table.

‘Good,’ I said. ‘Really good.’

‘Dreadful commute,’ Dad said.

‘Awful,’ I agreed. ‘And that’s why we’ve made a decision.’

Dad and Barb looked at me as I took a breath and explained what we were doing.

‘It’s a lovely house,’ I said. ‘And we’re just renting, though Ben says the landlord mentioned he’d be willing to sell if we like it.’

Barb smiled at me.

‘It sounds wonderful,’ she said. ‘But won’t it mean you commuting instead?’

There was a pause.

‘Well,’ I said. ‘Actually.’

Dad took his glasses off and rubbed the bridge of his nose and I felt my confidence beginning to desert me.

‘Actually?’ he prompted.

‘Actually, I’ve handed in my notice,’ I said. I picked up my sparkling water and swigged it, wishing it was gin.

Barb and Dad looked at each other.

‘That’s a big decision,’ Barb said carefully.

‘It is,’ I said. ‘But we’re confident it’s the right thing to do. Ben’s salary is good enough for us to live on, and I’ve got my writing.’

Dad nodded as though he’d reached a decision. ‘You’d be best taking a sabbatical,’ he said. ‘What did they say when you asked about that? If they said no, you’ve probably got cause to get them to reconsider. I can speak to Pete at my old firm, if you like? He’s the expert on employment law …’

‘Dad,’ I said. ‘I didn’t ask about a sabbatical, because I don’t want to take a sabbatical. I’m leaving my job and I’m going to write full-time. It’s all planned.’

Dad looked at me for a moment. ‘No, Ella,’ he said. ‘It’s too risky. What if Ben’s job doesn’t work out? Or the boys don’t settle? Have you checked out the school for Oscar? He’s a bright little lad and he needs proper stimulation. And don’t even think about selling your house in London. Once you leave London you can never go back, you know. Not with house prices the way they are.’

‘Dad,’ I said again. ‘It’s fine. We know what we’re doing.’

‘I’ll phone Pete, now,’ Dad said. ‘Now where did I put that blasted mobile phone?’

‘Dad,’ I said, sharply this time. ‘Stop it.’

Dad winced. ‘Keep your voice down, Ella,’ he said. ‘What’s wrong?’

I shook my head. ‘I knew this is how you’d act,’ I said. ‘I knew you wouldn’t want me to give up work, or for us to move house.’

‘I just worry,’ Dad said.

I felt a glimmer of sympathy for him. Of course he worried. But I wasn’t his little girl any more and we didn’t have to cling to each other like we were drowning, like we’d done when I was growing up.

‘Don’t,’ I said, more harshly than I’d intended. ‘Don’t worry. I’m fine. Ben’s fine. The boys are fine.’

Barb put her hand over Dad’s as though urging him to leave things there, but Dad being Dad didn’t get the message.

‘I think I should phone Pete,’ he said. ‘Just in case.’

I pushed my chair back from the table and stood up. ‘Do not pick up your phone,’ I said. ‘Don’t you dare.’

Dad and Barb both looked stunned, which wasn’t surprising. I’d never raised my voice to Dad before. I’d never even disagreed with his choice of takeaway on movie night.

‘Ella,’ Dad said. ‘I think you’re over-reacting a bit.’

But that made me even more determined to put my point across.

‘I’m not over-reacting,’ I said. ‘I want you to understand what’s happening here. I’m leaving my job, and we are moving to Sussex. Which, by the way, means we will be nearer to you than we are now. I thought you’d be pleased about that.’

My voice was getting shriller and I felt close to tears, but as Dad stared at me, shocked into silence, I continued. ‘I know it’s risky, but we have decided it’s a risk worth taking. Because, Dad, you know better than anyone that things can go wrong in the blink of an eye. You know that.’

Dad nodded, still saying nothing.

‘So it’s happening. And I knew you wouldn’t approve. And I’m sorry if this makes me difficult. Or if me doing something that you don’t like means you don’t want me in your life any more. But it’s happening.’

‘Ella …’ Dad began. ‘Ella, I don’t understand.’

‘Oh you understand,’ I said, all my worries about the move and about telling him spilling over. My voice was laden with venom as I leaned over the table towards him. ‘You understand. I’ve always been a good girl and done what you wanted me to do, haven’t I?’