скачать книгу бесплатно

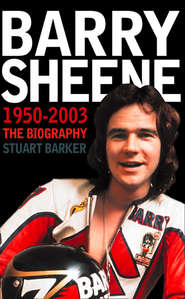

Barry Sheene 1950–2003: The Biography

Stuart Barker

The definitive life story of the seventies world 500cc motorcycle champion Barry Sheene – the Brit whose death-defying crashes and playboy lifestyle made him the most famous bike racer on the planet. Written by the only journalist to have ridden on the roads with him, and featuring interviews with closest friends, team mates and former rivals.Born in London's East End in 1950, Sheene was introduced to motor sport at the age of five, with his father Frank building him his first ever motorbike.His story traces his humble beginnings as a maverick opposed to every educational influence, through an apprenticeship as a part-time rider and full-time mechanic, to a works team racer, with a host of diversions in pursuit of the opposite sex.It charts his success between 1975 and 1982, a golden period during which Sheene won more international 500cc and 750cc Grand Prix titles than anyone, including the world 500cc title in 1976 and 1977. This despite the horrendous carnage from a series of near-fatal crashes from which Sheene miraculously survived and overcame, against all odds.Outside the sport, Sheene discovered an acting talent, appearing in the ITV show Just Amazing and in numerous TV commercials, making him a household name. On his retirement, he found fulfilment (and a friendlier climate for his battered body) in Brisbane as an expert motor sport commentator and an accomplished businessman. After being diagnosed with cancer in 2002 he shunned conventional treatments, preferring natural remedies, but died early in 2003.This is the complete portrait of perhaps the greatest circuit racer of them all.

BARRY SHEENE

1950–2003

THE BIOGRAPHY

STUART BARKER

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_acfcb368-4db4-5604-9799-a1e4113b1412)

Thorsons Element

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublisbers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in 2003

This paperback edition first published in 2004

© Stuart Barker 2003

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007161812

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2016 ISBN 9780007378586

Version: 2016-01-05

DEDICATION (#ulink_4f2159dd-d0a3-53e9-af64-d79065d8ab4c)

For my parents, Jim and Josie Barker,

for starting this whole thing.

CONTENTS

Cover (#u0cc9b168-dcca-5e23-8587-86b080535109)

Title Page (#u00168d07-36d5-5c9d-98d2-63a2c22e91a0)

Copyright (#u4e730787-b2ef-5035-b84d-b5764991e638)

Dedication (#u5913b042-8783-5984-a241-c5df6c2bce81)

Introduction (#u3a010c60-3100-5181-9c40-d92a91f564c0)

1 Cockney Rebel? (#ub941ff92-8998-59dd-b685-3df2b6ad897c)

2 The Racer: Part One (#u703ff5f4-5527-5593-a412-c770b495713f)

3 Playboy (#ub756a25f-a504-520e-9ef8-1ebcf3133321)

4 No Fear (#litres_trial_promo)

5 The Racer: Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

6 The Great Divide (#litres_trial_promo)

7 The Racer: Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Crusader (#litres_trial_promo)

9 The Racer: Part Four (#litres_trial_promo)

10 What It Takes (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Never Say Never Again (#litres_trial_promo)

12 Cancer (#litres_trial_promo)

13 A Star Without Equal (#litres_trial_promo)

Major Career Results (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Select Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_e8a4d2c5-389e-5d29-b535-0905bc00a09c)

‘I’m not going to let fucking cancer get in the way of me enjoying myself.’

It was like nothing had ever changed. The famous Donald Duck logo on the black and gold crash helmet could just be made out as the tall, gangly rider tucked in behind the bike’s screen, reducing wind drag to gain a fraction of a second over his pursuer. The equally famous number seven, crossed through European-style, was emblazoned on the bike’s bodywork as it had been almost 30 years before. It had always been lucky for him. Maybe it could be again.

His 51 years counted for nothing when he was on a motorcycle; it was as much a part of him as the plates, pins and 27 screws that held his legs together. The smooth but aggressive riding style, the determined and sustained attack, could all have belonged to a 20-year-old kid with a fire in his belly and a burning desire to win against the odds. Any odds.

Behind him, the 1987 500cc motorcycle Grand Prix world champion Wayne Gardner tried everything he knew to close the 1.3-second gap. But despite being 10 years younger and having a bike which was 20mph faster than the man out front, there was nothing he could do to get past. The distinctive riding style of the race leader hadn’t changed since he’d started racing bikes in 1968, and his desire to win appeared to be no less now than it was then. It was as if he still had something to prove.

The crowd, as ever, yelled their delight at the on-track bravado of the man in black, urging him on, willing him to make that decisive break, wanting him, needing him to dig deeper to secure a victory. Many of them had been teenagers when they first thrilled to their hero’s titanic battles with the best riders in the world, most of the races televised on ITV’s Saturday-afternoon World of Sport programme – warm, comforting memories of a childhood long gone. There were thousands in attendance who wouldn’t even have had an interest in motorcycles had it not been for the influence of the man who was out there throwing his bike hard over from side to side, skimming his knees off the Tarmac with a grace and style all of his own and gunning his steed down the straights as fast as the laws of physics would allow.

For the vast majority of the crowd, there was only one rider in the race; they would love him, applaud him and later mob him whether he came first or last. But Barry Sheene wasn’t accustomed to coming last. Even after 18 years of retirement from the sport that made him an international superstar, a multi-millionaire and one of the true icons of the seventies, he was out there proving he still had what it took to win races.

The more imaginative among the packed grandstands and trackside enclosures could have transported themselves, mentally if not physically, back to the halcyon days of the seventies when Sheene was on top of the world as the most famous motorcycle racer in history, a pin-up glamour boy for millions of teenage girls and a Boys’ Own hero for an entire generation of lads. Dads and mums alike now took great pleasure in pointing out to their own kids the very man who had quickened their young pulses nearly three decades earlier.

But even the most nostalgic of spectators were forced, however reluctantly, to admit that things were different this time round. For starters, it was 2002, not 1976. And this was not a 500cc Grand Prix World Championship race, it was a classic bike race being staged at the Goodwood Revival event organized by Sheene’s close friend, the Earl of March. Sheene’s bike, a classic sixties Manx Norton, was a far cry from the vicious 130bhp, 170mph monsters he used to tame on race tracks around the world for the pleasure of millions. But the fans didn’t care. It was still Barry Sheene out there, he was still racing a bike, he was still winning, and that was all that mattered.

The most significant change of all, the thing that really brought a lump to the throats of so many and which made Sheene’s eventual victory over Gardner even more remarkable and emotional, was the recently divulged fact that Barry had cancer. This was the first time he had appeared in public since being diagnosed. The poignancy of his win was not lost on the 80,000-strong crowd who realized they were probably witnessing Sheene’s last-ever race.

Barry had been diagnosed with cancer of the oesophagus and upper stomach just a few weeks earlier, and there were more than a few tears shed as he crossed the line, removed his helmet and waved to the masses on his victory lap. He had come a long way to get to Goodwood in the sleepy West Sussex countryside – from the other side of the world, in fact. An 18-hour direct flight from Australia is gruelling enough for most passengers, never mind one suffering from cancer. But to ride flat-out against some supremely talented opposition, including former world champions Gardner and Freddie Spencer, and to eventually take the race win gave all his fans reason to believe that this time cancer had picked the wrong body. Sheene was a fighter and a winner; he had proved it many times before. Surely, if anyone could beat the most dreaded of diseases, it was he.

When news of his illness broke, Sheene shocked fans around the world by announcing he would not be undergoing invasive surgery or chemotherapy to treat his condition. Instead, he would rely on alternative cures and a special frugal diet. Sheene had already lost a stone off his slight frame by the time he appeared at Goodwood, and orthodox oncologists warned that he risked malnutrition by continuing with the diet. But Sheene has always done things his own way, and he was adamant when interviewed by Motor Cycle News: ‘I’m not going to be fighting this in the conventional way. I won’t subject my body to chemotherapy. I’m putting my faith in the natural way.’

Typically for a man who had made a living out of cheating death, Barry put a brave face on his illness and already had his quips and quotes worked out for the media. ‘I don’t like cancer, but it’s growing on me’; ‘If I don’t beat this my wife’s going to kill me.’ These were just two of the lines he bandied about like a stand-up comic living in denial of the very real risk to his life. Sheene also insisted that he wasn’t ‘going to let fucking cancer get in the way of me enjoying myself’ and admitted that his second thought upon hearing his diagnosis was that he might have to miss the Goodwood event. It hadn’t taken long for him to re-establish control, pack a suitcase and catch a flight; he wasn’t about to let down his fans. Anyway, it wasn’t as if fighting for survival was something new to Sheene. In the past he had astounded some of the most respected doctors and surgeons in the world with his ability to recover from serious injuries in unheard-of time spans.

Well-publicized X-rays of his shattered legs from two horrific high-speed crashes played as much a part in making him a household name as any of his victories on the race track. In 1975, his rear tyre blew out at 178mph on the notorious banked section of the Daytona Speedway in Florida. The crash, captured by a television documentary crew who were following Sheene at the time, was shown on TV news programmes around the world, and the incident made Barry famous overnight. His leg was broken so badly it was twisted up behind him, out of sight, making him think he had lost it. He also lost shocking amounts of skin and broke his forearm, wrist, six ribs and a collarbone, as well as suffering compression fractures to several vertebrae. On top of that, damage to his kidneys meant he urinated blood for several weeks. Despite the serious nature of his injuries, Sheene did not lose his 60-a-day passion for strong, unfiltered cigarettes – he preferred the French brand Gauloises, but would happily smoke any brand that was being offered around – and insisted on being wheeled out of the hospital on his bed from time to time so that he could smoke. The hole he drilled in the chin bar of his crash helmet so that he could have a puff on the starting grids at race meetings remains the stuff of legend in bike racing circles, but no one was laughing any more. Sheene’s heavy smoking habit, which had started when he was just nine years old, was one factor cited as a possible cause of his cancer.

The Daytona disaster was the kind of accident that would take ‘normal’ people months, if not years, to recover from. Many would never overcome the psychological scars of remembering every bone-crushing, skin-shredding second of their crash, and would certainly never contemplate getting back on a motorcycle again, but then most people aren’t Barry Sheene. He was racing again just seven weeks later with an 18-inch pin in his left thigh bone, and went on to win his first World Championship the following year.

Crashes are common in bike racing, but big ones like Sheene’s Daytona incident are rare – at least, it’s rare to survive them. Broken arms or legs are frequent injuries, as are abrasions, damaged tendons and general cuts and bruising, but few people live through, or are unfortunate enough to have in the first place, crashes at such extreme speeds. Sheene had not one but two. The second happened seven years and two World Championships later (Barry retained the title in 1977 and was awarded an MBE for doing so) at the Silverstone circuit in England, and it was every bit as bad, if not worse, than the first. Sheene struck a crashed bike which was lying on the circuit just above a blind rise and its fuel tank instantly ignited causing a massive explosion. He had been travelling at around 165mph at the moment of impact. Moments later, another bike hit the wreckage causing another explosion; the resulting carnage resembled the aftermath of a terrorist bombing. Sheene’s already fragile legs had been smashed again, this time more gravely than before, and he also suffered injuries to his head, chest and kidneys.

But while his body was in bad shape, his mental attitude remained as gritty as ever. He told gathered reporters from his hospital bed that ‘Broken bones are a mechanical problem. You can fix them.’ Sheene’s surgeon, Nigel Cobb, inserted plates, pins and a total of 27 screws into his famous patient’s legs and triggered a barrage of schoolboy gags about Barry Sheene and airport metal detectors. But his rate of recovery, once again, was phenomenal.

If Barry Sheene had been a star before his Silverstone crash, he was a superstar after it – and, it appeared, an invincible one. No bike racer before or since has commanded anywhere near the same amount of media coverage as Sheene. It is inconceivable in the current climate of the sport to imagine a national newspaper running a front page story on a bike racer just because he’d met a new blonde girlfriend, and how many other bikers could have starred alongside boxer Henry Cooper in a terrestrial TV advert for a body scent encouraging users to ‘Splash it on all over’? How many racers counted members of the Beatles as close personal friends and dined with Hollywood legends such as Cary Grant? None.

As well as being a world champion racer, Barry Sheene was a marketing phenomenon, gaining exposure for his growing attachment of sponsors in areas even they couldn’t have imagined. He co-hosted ITV’s Just Amazing! show in the eighties and was the star attraction at the 1982 BBC Sports Personality of the Year awards when he rode his new Suzuki onstage and announced he’d be leaving Yamaha to join Suzuki for the following season. He starred as himself in the (very bad) movie Space Riders, and appeared on every major television show of his time from Parkinson to Swap Shop and Jim’ll Fix It to Russell Harty. But perhaps the most enduring legacy of Barry’s fame is that he’s still the only biker the general public as a whole have heard of. Ask any one of them to name a motorcycle racer and they’ll invariably say Barry Sheene. The same thing happens whenever anyone, young or old, is attempting to go too fast or to do something stupid on a two wheeler, be it a motorcycle or a pushbike. The response from policemen and dads alike is always the same: ‘Who do you think you are, son, Barry Sheene?’

Everyone appreciated a British sportsman who was capable of beating the world in an era when such a thing wasn’t (and, sadly, still isn’t) commonplace. Sheene remains the last British rider to win a Grand Prix World Championship despite the fact that he last held the title 25 years ago. Even more than his ability to win, the public applauded his guts and bravery as he came back not once but twice from injuries that would have ended any other sportsman’s career. After his Silverstone crash, Sheene was extremely lucky to be able to walk again, let alone be fit enough to win motorcycle races.

It was this fighting spirit, this never-say-die attitude, which gave hope to millions when Barry announced he was ready to battle cancer and wouldn’t be beaten in the fight. With typical bravado, he commented shortly after being diagnosed that it was ‘a complete pain in the arse’, and vowed to deal with it.

It was a great irony that a man who had spent 16 years risking his life on a motorcycle should retire from the sport still in one piece only to face death from a creeping, silent and devastating opponent from within. The irony was not lost on those who remembered that Britain’s other great champion motorcyclist, Mike Hailwood, was killed in retirement by an errant lorry driver while returning in his car from his local fish and chip shop. Sheene’s former rivals, as well as his constant supporters, were without exception shocked by the news of his cancer, and all of them rallied round to offer words of support and encouragement. Old differences were forgotten. The only thing that mattered was for Sheene to concentrate on beating his disease.

Barry Sheene was the first, and arguably the last, truly mainstream motorcycle racer who could genuinely lay claim to being a household name. In truth, there was no need for him after 1982 to continue to risk life and limb on a 180mph motorcycle when he was already a multi-millionaire with a twelfth-century, 34-bedroom mansion in Surrey, his own helicopter and a guaranteed career outside racing whenever he decided to call it quits. But that’s what made him Barry Sheene: his determination to be the best, to be the fastest, never to give up, to push a 130bhp motorcycle past its limits and bring it back safely again. Sometimes he didn’t bring it back safely; sometimes the bike would savagely bite back and spit Sheene off like an angry rodeo steer ditching its rider. But Sheene always got back on. He always returned to show the bike, and his public, who was boss.

But at the age of just 51, Sheene had a new and even more deadly opponent than a badly behaved, viciously powerful motorcycle, a more lethal foe than speed itself, and a more cunning enemy than any he had faced off before. He had cancer. Without doubt, it would prove to be the toughest battle of his impressive but painful career, but on that day at Goodwood there seemed to be no one in the world with a mindset more suited to combating the biggest killer of modern times. He had cheated death many times before. All he had to do was cheat it one more time.

CHAPTER 1 COCKNEY REBEL? (#ulink_6677476f-cf9b-5d92-a53a-61199b9669ed)

‘For me, school was like a bad dream. Every minute of every day was murder.’

If you’re going to be a motorcycle racer, you’re going to have to get used to pain, discomfort and hospital food. Barry Sheene had a very early introduction to all three. Almost from the moment he was born he suffered from infantile eczema which caused him, and his mother Iris, years of sleepless nights as Barry tossed around in his cot scratching and clawing at every part of his tiny body seeking a moment’s respite from the maddening, all-enveloping itch. As anyone who’s ever had the misfortune to suffer from severe eczema will testify, it’s not a very pleasant condition. Barry’s torment increased at the age of two when he also developed chronic asthma. The infant Sheene therefore had to endure the double misery of an infernal itch while struggling for breath at the same time. Almost from the moment he was born, he learned about tolerance to pain, about how to overcome illness, about how never to give up in the struggle back to health. These experiences would stand him in good stead.

Sadly, 11 September is a date that will now always be remembered for the wrong reasons following the terrorist attack on New York’s World Trade Center in 2001, but in 1950 the date was significant in the Sheene family’s London household because it was when Frank and Iris welcomed into the world their second child, having already given birth to a daughter, Margaret. Barry Stephen Frank Sheene was born at 8.55 p.m. on a Monday evening and was later taken home to a four-bedroom flat in Queens Square, Holborn, just off Gray’s Inn Road in London WC1.

Much has been made of whether or not Sheene, having been born and raised in WC1, can actually lay claim to being a genuine cockney. Traditionally (and according to the Collins Dictionary definition), the only qualification required for the title is to be ‘born within the sound of the bells of St Mary-le-Bow church’, or the ‘Bow Bells’ as they are more commonly referred to. Since weather conditions, white noise and the relative abilities of one’s hearing will naturally affect the range of the bells, it appears to be a moot point in Sheene’s case. There is no strict dividing line painted around London to define which streets are ‘cockney’ and which are not, but it’s probably fair to say that those living further east in the city disputed Sheene’s claim while the rest of the world happily accepted it. Still, Sheene was proud of his cockney roots and no one is in a position to deny him those roots with any authority.

Sheene’s father Frank, or Franco as he has always been affectionately called by his son, was the resident engineer at the Royal College of Surgeons. The family’s flat went with the job, as did a fully equipped workshop out back which was to prove of significant importance to the young Barry in the years that followed. The family was neither wealthy nor poor; Barry would later describe his family’s socio-economic status as ‘slightly above average’. Iris worked at the college as a housekeeper to top up the family income and Frank brought in some handy extra cash working as a mechanic and bike tuner in the evenings. By the mid-sixties he had earned such a good reputation as a two-stroke tuner that world champions including Bill Ivy and Phil Read came knocking on his door. The former was a hero to Barry, but he was sadly killed in a racing accident when Barry was still young. The latter would start out as a friend before falling out with Barry in 1975 over an alleged bribe attempt, more of which later.

Work became plentiful for Frank, and his skills were highly valued by any racer who had the money and wanted his motorcycle to go faster. It was Frank’s skill with all things mechanical that saved his son’s manhood after a nightmare incident when Barry was just four years old; eczema and asthma notwithstanding, his well-being suffered a further setback, as Michael Scott related in his 1983 book Barry Sheene: A Will to Win. According to Iris Sheene, Barry had been playing with a clockwork toy train while being bathed in the kitchen sink when he suddenly let out a terrible scream. When a panicked Iris turned to see the cause of the commotion, she noticed that the bodywork of the train was missing (probably due to Barry’s early curiosity for all things mechanical) but the cogs and mechanisms had caught his foreskin and were still churning away, tearing into the sensitive flesh of her child’s genitalia. A traumatized Barry was rushed to a nearby hospital where his father exercised all his skill in dismantling the train’s workings while desperately holding back the tightly loaded spring that was the cause of his son’s agony. Eventually Frank worked the train loose at the expense of much blood and some tissue, but Barry would have much to thank his father for in later years when he came of age. Had it not been for his father’s skill and quick thinking, Barry Sheene the playboy might never have been. It was a fortunate escape, and by no means Barry’s last.

Frank began to pass on his considerable mechanical knowledge to his son from a very early age. Before her death from a brain tumour in 1991, Iris recalled, ‘When he [Barry] was only eighteen months old, I can remember him wandering around in his dungarees with a spanner in his hand.’ There was to be an early introduction to race meetings, too: from the age of four Barry was being dragged around bike events, soaking up the addictive sights and smells of paddocks all over England and, on occasion, overseas as well. Frank had raced a variety of motorcycles as an amateur for many years, both before and after the war (he won a trophy on the famous Brooklands circuit just before war broke out). He was a competent and enthusiastic club racer but never really World Championship material. Nor did he have the longing to be a world champion; his interest lay more in the preparation and tuning of machinery, and he was most certainly world class at that. Further cementing the Sheene family’s ties with motorcycle racing was Frank’s brother Arthur, himself an extremely capable speedway rider for Coventry and a loyal member of ‘Team Sheene’ once Barry took up racing.

Unlike his son, Frank was a keen supporter of the Isle of Man TT races which at that time was still the most important bike event in the world. It was when he took five-year-old Barry to the Island for what was already his second TT trip that the youngster found himself having health traumas yet again, and this time it really did look bad. Set as it is in the middle of the Irish Sea, the Isle of Man’s wet and misty climate is not particularly suited to asthma sufferers. Barry suffered such a severe attack that he quite literally turned blue. He was rushed to Nobles Hospital where he was detained for three days until his breathing returned to normal. It was the start of an unhappy relationship with the Isle of Man which would have far-reaching consequences in later years.

But Sheene was always quick to spot an opportunity and was extremely adept at turning ill fortune to his advantage. Rather than seeing his asthma as a disability, he found ways to make it work for him. For starters, it was a good excuse for getting out of school sports, of which he was never fond; it was an even better excuse for playing truant, and he regularly told teachers he had asthma clinics to attend. To be fair, sometimes he did have legitimate appointments, but there were many more occasions when he didn’t. His truancy habit was made considerably easier to sustain when Sheene found a pile of pre-stamped appointment cards on one particular visit to a clinic. Spotting a golden opportunity, he promptly pocketed the lot, got a friend to sign them, and from then on enjoyed what amounted to a healthy supply of get-out-of-school-free cards. They were not wasted.

Sheene’s hatred of school has been well documented. It’s not that he didn’t have an aptitude for learning – as he would later prove by teaching himself five languages and learning to pilot a helicopter – it was just that he didn’t like it. And when Barry Sheene didn’t like doing something, he didn’t do it. He didn’t like the work, he didn’t like the discipline, and most of all he didn’t like the teachers. ‘For me, school was like a bad dream,’ he said. ‘Every minute of every day was murder. I hated being told what to do and when to do it by a bunch of teachers who always wanted to try to insult me or belittle me.’ Sheene didn’t respond well to being told what to do. If he was given a free rein, as he was in Frank’s workshop, he displayed a fantastic ability to learn, but he resented the apparently pointless rigidity of the school environment. That stubborn streak would remain with him throughout his life, and it helped him amass a fortune as a property developer in Australia when he stopped racing motorcycles. Barry’s headmaster at St Martin’s in the Fields once told Iris that her son could have been top boy if he had only put his mind to it, but Barry simply wasn’t interested. He had decided at a very early age that he would do things his own way or not at all. That same headmaster sent his former pupil a letter of congratulations when he won the 500cc World Championship in 1976, a fact of which Barry was understandably proud. It was, after all, a written acknowledgement of achievements attained without the aid of formal education.

Sheene brought up the subject of his schooldays again in 1978 when he appeared on the Parkinson show. Speaking of one teacher whom he had particularly disliked (he diplomatically stopped short of naming him) he said, ‘I was caught for This Is Your Life the other night. I thought, I hope they don’t bring that teacher on because it would be the first punch-in. I feel bitter about it. I think it is one of the things that’s driven me on, because in the back of my mind there’s always this guy saying you will never make anything of your life.’

At one point, it looked more likely that Barry Sheene would become famous as a musical star rather than as a bike racer as he landed a job as an extra in the musical Tosca in Covent Garden, not far from his house. Sheene had been spotted fighting by a teacher who was looking for extras and she’d asked him if he could sing as well as fight. He replied that he could ‘at a push’, auditioned for the part of a scrapping, singing youth, and ended up sharing the stage with world-renowned opera singer Maria Callas. Sheene explained, ‘She [the teacher] was recruiting lads as extras … and another young boy and I were auditioned and given small parts in the first act to scrap in a churchyard scene. Being cast as a singing, fighting hooligan wasn’t altogether at odds with the way I behaved in real life! Sharing the stage with Tito Gobbi and Maria Callas at such a famous place became one of my most vivid childhood memories. I even had to sing. Best part of it was it meant getting off school.’

To escape the misery of school when he wasn’t treading the boards, Barry would often sneak off behind the bike sheds to chain-smoke cigarettes. It seems incredible that someone with chronic asthma would want to smoke, but Barry had taken up the habit when he was just nine years old. Most parents would have been horrified to catch their child smoking, although to be fair on Mr and Mrs Sheene attitudes towards smoking have changed markedly since the fifties and sixties; when Frank caught Barry at it when he was 11, he simply handed him two Woodbines (extremely strong, non-filter cigarettes) and said that if Barry could finish them off he was free to smoke. Fifteen minutes later, Barry was free to smoke. He was soon openly sharing his cigarettes with his family. Years later, his greatest joy having returned to the paddock was his first post-race cigarette. ‘For no other reason than for the sheer pleasure it brings, my first priority upon dumping the bike in the pits is to have a cigarette,’ he said. ‘I might have had my last drag on the start line [through the hole drilled in his helmet’s chin bar] but I crave one immediately I’ve finished the race, not as a means of calming the nerves but simply because it has been over an hour since my last one. For a heavy smoker like myself, that’s a long time!’

Drinking, however, was never one of his vices, although he was as prone to getting carried away on nights out as the next man, and he did once take sadistic pleasure in getting a schoolfriend drunk during a lunch break in what has become one of the most often-repeated stories from Sheene’s childhood. Barry plied his hapless chum with a concoction of spirits from his father’s drinks cabinet before dragging him back to the classroom to observe the effects. His friend was so intoxicated that he needed to be rushed to hospital to have his stomach pumped. Sheene, not surprisingly, thought he was in for big trouble when his parents were called in to school to see the headmaster, but Frank was his usual laid-back self, dropping cigarette ash all over the headmaster’s pristine carpet as he explained his son’s actions by resignedly announcing that ‘Boys will be boys.’

Barry first got drunk at the Isle of Man TT in 1960 when he was only 10 years old after guzzling two glasses of champagne given to him by Gary Hocking, who had just finished second in the Junior TT. The experience was enough to put him off touching another drop of alcohol until he was 16. Even after that he claimed he never became a heavy drinker, although he did later develop a passion for fine wines and took great pride in his well-stocked cellar.

Girls were another matter altogether. Perhaps because he’d come so close to losing his manhood as a child, Barry seemed determined to put it to good use as soon as the opportunity presented itself. It finally did over a snooker table in the crypt of a local church when Barry was 14, with a girl whose name he could never remember. From that point on he never looked back. He’d eventually become so famous for his womanizing that he would make front-page news after being photographed leaving a nightclub with a new date, and he would also be selected as a judge for the Miss World contest.

But whatever mischief Barry got up to in his youth, he never rebelled against his parents. The Sheene family was a very tight-knit unit and it stayed that way throughout Barry’s racing career, with Frank helping on the bikes and Iris keeping hot food and drinks flowing for the family and their guests. Barry never treated his parents with anything other than full respect, though he often fought with his elder sister Maggie. ‘Team Sheene’ would become legendary round the paddocks of the world, Frank and Iris providing all the back-up their boy needed when he was racing bikes. The trio were practically inseparable.

Unlike some parents who attempt to live out their own unfulfilled dreams through their children, Frank never pushed Barry into riding motorcycles, but then he didn’t have to. When he offered the five-year-old Barry a motorcycle, the youngster jumped at the chance, like most boys would. The bike was a damaged 50cc Ducati that Frank had rebuilt, and Barry spent hours riding around the spacious back yard of the Royal College of Surgeons on the little four-stroke single, driving the neighbours to distraction. The machine actually had two gears, but Barry, not knowing how to change gears, only ever used one. It was still good enough to reach speeds of around 50mph.

Ironically, it wasn’t hurtling around on a motorcycle which caused Barry’s first serious injury; it was a pushbike accident at the age of eight which resulted in a broken arm. After the arm was plastered, Sheene told his mother that he’d always wanted to break his arm (again, like most schoolboys) and was well chuffed with his plaster trophy.

The little Ducati was eventually replaced by a 100cc Triumph Tiger Cub which Barry took to race meetings so he could potter around in the nearby fields, of which there wasn’t an abundance in central London. He had tried riding the Tiger round the roads near his home but a couple of run-ins with the law had put an end to that, even though the coppers had taken it easy on Barry as they regularly utilized Frank’s services for repair work. When he wasn’t riding his own bike, Barry would take his dad’s race bikes out for short test runs at disused airfields or racing paddocks, all the time developing his skill for analysing how the bikes were running. Sheene’s developmental and analytical skills became finely honed during these years, and they played a big part in his success. But that was no real surprise when one considers that he could strip and rebuild an engine by the age of 12 and was riding real racing motorcycles when his class-mates were still mastering the art of pedalling. Barry recalled getting plenty of snotty looks as a kid when he suggested to puzzled and frustrated riders in the paddock what might be wrong with their bikes just by listening to them being revved. But those who were modest enough to take his advice usually found (probably to their amazement) that the advice was good. Indeed, Sheene became quite the little paddock consultant for any rider whose ego was willing to accommodate the fact that a child knew more about engine mechanics than he did.

Frank Sheene’s bikes were among the best in the country in the sixties and were in demand by many of the top racers of that era, and Barry was fast catching his father up on technical know-how. So much so that by the time he was 14 he was a good enough mechanic to be offered a job looking after race bikes, even though it didn’t pay. But for someone who hated school as much as Barry did the opportunity must have felt like a dream come true: he was asked if he would like to spend a month working as a mechanic in Europe for American Grand Prix racer Tony Woodman. Needless to say, he didn’t have to be asked twice. Frank, fully approving of what he saw as a unique chance for his son to see something of the world and to gain work experience while other kids were stuck in school only reading about foreign lands, gave his son £15 for the month to cover all expenses from food, drink and cigarettes to ferry fares. It was a very modest sum, even in 1964, but Barry, showing a thriftiness that would later become a hallmark, managed to return from the trip with change in his pocket. His parents signed him off school for a month, blaming another bout of illness.

There were few luxuries available and food was scarce, but it was an incredible experience for a boy of 14 and an invaluable insight into the Grand Prix world he would soon come to dominate. And the fact that Woodman was not there just to make up the GP numbers but was a genuine contender made Sheene’s position even more remarkable, a real testament to the skills he had acquired. The trip, which embraced visits to the Salzburgring and the Nurburgring for the Austrian and German GPs, went well. Barry could not have had much interest in returning to school after such an eye-opener, but he still had one year to complete before being officially allowed to leave so he got on with it as best he could. Woodman, incidentally, was later paralysed after breaking his back in the North West 200 road races in Northern Ireland. It was a harsh reminder, if Sheene needed one, that racing motorcycles is a risky business, but at that point Barry showed no signs of wanting to race anyway. Like his father, he was more than happy working on bikes instead of riding them.

His final year at school completed, Sheene was at last free to try his luck in the world at large. He left formal education without a single qualification to his name and in the knowledge that the only thing he’d topped at school was the absenteeism list. But one good thing, aside from Barry’s utter relief, came from leaving school: his asthma attacks all but disappeared. They had always been made considerably worse when Barry was stressed or emotionally upset, and he felt there was no mystery attached to their clearing up almost as soon as he left school: it was a sure measure of how much he had dreaded that establishment. He couldn’t have been happier when it was time to turn his back on it for good.

It seemed obvious from his early-learned hatred of authority that Barry wasn’t going to settle comfortably into just any old job under any old boss. As he said, ‘I had never experienced working for someone other than Frank and I wasn’t quite sure how I would take to someone giving me orders.’ But with no formal qualifications, he wasn’t going to be offered many decent jobs either. Deep down, however, both Sheene and his parents knew that his profound mechanical knowledge would somehow see him through. Frank had taught him all he needed to know about stripping and rebuilding engines, about how to squeeze every last ounce of power out of a motorcycle. Surely that knowledge alone would stand him in good stead?

But being a mechanic didn’t seem to be top of Barry’s job-hunting list. In fact, initially he didn’t have a clue what he wanted to do, and he soon found himself drifting in and out of jobs like most young people trying to find their feet in the world. Eventually he landed a job in a car spares warehouse unloading parts into different bins. The work was neither glamorous nor stimulating, and it paid a measly £5 a week, of which Barry pocketed just 75 shillings after paying tax and national insurance. Needless to say, he didn’t stick at the job for long. Within a few months he had moved on to a new position which was infinitely more exciting and one small step closer to his destiny: he became a motorcycle despatch rider.

Having failed his bike test first time round because the number plate fell off his machine (in his 1976 book The Story So Far, Sheene wrote that he took his test on a 75cc Derbi, but in 2001 he claimed it was on a BSA Bantam), Barry passed at his second attempt, although he told Bike magazine years later that ‘In no way did it [the bike test] prepare me for the road. Absolutely not. In the same way that shagging your girlfriend in a Transit van does nothing to prepare you for married life.’ Having passed, Sheene was handed a BSA Bantam (which perhaps explains his confusion over which bike he had passed his test on) with which to deliver proofs and copy around London for an advertising agency. His wages jumped up to a healthier £12 a week, and more importantly for the girl-mad young Sheene, he got to meet lots of glamour models.

Needless to say, no motorcycle could be taken back to the Sheene household without Frank giving it the once-over, and the British-built Bantam was no exception. Frank soon had it tweaked and tuned to reach a top speed of 80mph, which, through London traffic at any rate, was about as fast as even Barry Sheene dared to go.

Barry enjoyed his stint as a courier, and no doubt it helped to hone his riding skills since travelling through heavy London traffic at speed is no easy task. But at the time money was more important than job satisfaction, and when a friend offered him more cash for sprucing up second-hand cars for his showroom, Barry gladly accepted.

After eighteen months of valeting cars it was time for another change, and Sheene took to driving a truck around London delivering antique furniture, quite often to television stage-sets. He had to lie about his age to get the job and had to show his prospective employers his dad’s driving licence which included the all-important HGV stamp, but somehow it worked and Barry found himself employed as a truck driver. The only problem was, he couldn’t drive a truck. This shortcoming was compounded when his new boss asked him for a lift in the truck straight after the interview. Sheene thought fast and insisted he had to have some time to check the truck over in the yard before he drove it, him being so safety conscious and all. His boss seemed suitably impressed and sought alternative transport, leaving his relieved new employee to drive round and round a nearby car park, familiarizing himself with the skills required to drive a heavy goods vehicle. Sheene took to the task easily, passed his month’s probation without any problems, and was once more to be seen despatching goods around London, albeit at a much more sedate pace.