Полная версия:

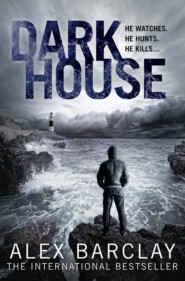

Darkhouse

ALEX BARCLAY

Darkhouse

Copyright

This is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street,

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2006

Copyright © Alex Barclay 2005

James Baldwin quote with the kind permission of

Gloria Smart for the Estate of James Baldwin

Cover design layout © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com

Alex Barclay asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008180874

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2010 ISBN: 9780007346875

Version 2016-05-17

Praise for Alex Barclay

‘The rising star of the hard-boiled crime fiction world, combining wild characters, surprising plots and massive backdrops with a touch of dry humour’ Mirror

‘Tense, no-punches-pulled thriller that will have you on the edge of your deckchair’ Woman and Home

‘Explosive’ Company

‘Darkhouse is a terrific debut by an exciting new writer’ Independent on Sunday

‘Compelling’ Glamour

‘Excellent summer reading … Barclay has the confidence to move her story along slowly, and deftly explores the relationships between her characters’ Sunday Telegraph

‘The thriller of the summer’ Irish Independent

‘If you haven’t discovered Alex Barclay, it’s time to jump on the bandwagon’ Image Magazine

Dedication

To Brian, my hero

And to my parents

‘The sea rises, the light fails, lovers cling to each other, and children cling to us. The moment we cease to hold each other, the moment we break faith with one another, the sea engulfs us and the light goes out.’

James Arthur Baldwin

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for Alex Barclay

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Alex Barclay

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

New York City

Edgy hands slid across the narrow belt, securing it in place on the tiny eight-year-old waist. Donald Riggs pointed to the small box attached.

‘This is like a pager, honey, so the police can find you,’ came his lazy drawl.

‘Because you’re going home now. If your mommy is a good girl. Is your mommy a good girl, Hayley?’

Hayley’s mouth moved, but she couldn’t speak. She bit down on her lip and looked up at him, beaming innocence. She gave three short nods. He smiled and slowly stroked her dark hair.

The fourth day without her daughter was the final day Elise Gray would have to endure a pain she could barely express. She breathed deeply through anger and rage, guilty that it was caused more by her husband than the stranger who took away her child. Gordon Gray’s company had just gone public, making him a very wealthy man and an instant target for kidnap and ransom. The family was insured – but that was all about the money, and she didn’t care about the money. Her family was her life and Hayley, her shining light.

Now here she was, parked outside her own apartment at the wheel of her husband’s BMW, waiting for this creep to call her on the cell phone he left with the ransom note. Yet it was Gordon who dominated her thoughts. The insurance company had told the couple to vary their routine but, good God, what would Gordon know about varying his routine? This was a man who brewed coffee, made toast, then lined up an apple, a banana and a peach yoghurt – in that order – every morning for breakfast. Every morning. You stupid man, thought Elise. You stupid man and your stupid, stupid, rituals. No wonder someone was waiting outside the apartment for you. Of course you were going to show up, because you show up every day at the same time, bringing Hayley home from school. No detours, no stops for candy, just right on time, every time.

She banged her head on the steering wheel as the cell phone on the seat beside her lit up. As she fumbled to answer it, she realised it was playing Sesame Street. He’d actually set the tone to Sesame Street, the sick bastard.

‘Drive, bitch,’ each word slow and deliberate.

‘Where am I going?’ she asked.

‘To get your daughter back, if you’ve been behavin’ yourself.’ He hung up.

Elise started the engine, put her foot on the gas and swung gently into the traffic. Her heart was thumping. The wire chafed her back. By calling the police in that first hour, she had set in motion a whole new ending to this ordeal. She just wasn’t sure if it was the right ending.

Detective Joe Lucchesi sat in the driver’s seat, watching everything, his head barely moving. His dark hair was cut tight, with short slashes of grey at the sides. He questioned again whether Elise Gray was strong enough to wear a wire. He didn’t know where the kidnapper would lead her or how she would react if she had to get any closer to him than the other end of a phone. He had barely raised his hand to his face when Danny Markey – his close friend of twenty-five years and partner for five – started talking.

‘See, you got the kinda jaw a man can stroke. If I did that, I’d look like an idiot.’

Joe stared at him. Danny was missing a jawline. His small head blended without contour into his skinny neck. Everything about him was pale – his skin, his freckles, his blue eyes. He squinted at Joe.

‘What?’ he said.

Joe’s gaze shifted back to Elise Gray’s car. It started to move. Danny gripped the dashboard. Joe knew it was because he expected him to pull right out. Danny had a theory; one of his ‘black and whites’, as he called them. ‘There are people in life who check for toilet paper before taking a crap. And there’s the ones who shit straightaway and find themselves fucked.’ Joe was often singled out. ‘You’re a checker, Lucchesi. I’m a shitter,’ he would say. So they waited.

‘You know Old Nic is getting out next month,’ said Danny. Victor Nicotero was a lifer, a traffic cop one month shy of retiring. ‘You goin’ to the party?’

Joe shook his head, then sucked in a sharp breath against the pain that pulsed at his temples. He could see Danny hanging for an answer. He didn’t give him one. He reached into the driver’s door and pulled out a bottle of Advil and a blister pack of decongestants. He popped two of each, swallowing them with a mouthful from a blue energy drink hot from the sun.

‘Oh, I forgot,’ said Danny, ‘your in-laws are in from Paris that night, right?’ He laughed. ‘A six-hour dinner with people you can’t understand.’ He laughed again.

Joe pulled out after Elise Gray. Three cars behind him, a navy-blue Crown Vic with FBI Agents Maller and Holmes followed his lead.

Elise Gray drove aimlessly, searching the sidewalks for Hayley as though she would show up on a corner and jump in. The tinny ringtone broke the silence. She grabbed the phone to her ear.

‘Where are you now, Mommy?’ His calm voice chilled her.

‘2nd Avenue at 63rd Street.’

‘Head south and make a left onto the bridge at 59th Street.’

‘Left onto the bridge at 59th Street.’ Click.

The three cars made their way across the bridge to Northern Boulevard East, everyone’s fate in the hands of Donald Riggs. He made his final call.

‘Take a left onto Francis Lewis Boulevard, then left onto 29th Avenue. I’ll be seein’ you. On your own. At the corner of 157th and 29th.’

Elise repeated what he said. Joe and Danny looked at each other.

‘Bowne Park,’ said Joe.

He dialled the head of the task force, Lieutenant Crane, then handed the phone to Danny and nodded for him to talk.

‘Looks like the drop-off’s Bowne Park. Can you call in some of the guys from the 109?’ Danny put the phone on the dash.

Donald Riggs drove smoothly, his eyes moving across the road, the streets, the people. His left hand moved over the rough tangle of scars on his cheek, faded now into skin that was a pale stain on his tanned face. He checked himself in the rear-view mirror, opening his dark eyes wide. He raised a hand to run his fingers through his hair, until he remembered the gel and hairspray that held it rigid and marked by the tracks of a wide-toothed comb. At the back, it stopped dead at his collar, the right side folding over the left. He had a special lady to impress. He had splashed on aftershave from a dark blue bottle and gargled cinnamon mouthwash.

He turned around to check on the girl, lying on the floor in the back of the car and covered by a stinking blanket.

It was four-thirty p.m. and five detectives were sitting in the Twentieth Precinct office of Lieutenant Terry Crane as Old Nic shuffled by, patting down his silver hair. Maybe they’re talking about my retirement present, he thought, narrowing his grey eyes, leaning towards the muffled voices. If it’s a carriage clock, I’ll kill them. A watch he could cope with. Even better, his boy Lucchesi had picked up on his hints and spread the word – Old Nic was planning to write his memoirs and what he needed for that was something he’d never had before: a classy pen, something silver, something he could take out with his good notebook and tell a story with. He put a bony shoulder to the door and his cap slipped on his narrow head. He heard Crane briefing the detectives.

‘We’ve just found out the perp is heading for Bowne Park in Queens. We still don’t have an ID. We got nothing from canvassing the neighbourhood, we got nothing from the scene – the guy jumped out, picked up the girl and drove off at speed, leaving nothing behind. We don’t even know what he was driving. This is just from the father who heard the screech from the lobby. We also got nothing from the package the perp dropped back the following day, just a few common fibres from the tape, nothing workable, no prints.’

Old Nic opened the door and stuck his head in. ‘Where’d this kidnapping happen?’

‘Hey, Nic,’ said Crane, ‘72nd and Central Park West.’ With no clues to his retirement present apparent in the office, Old Nic moved on, until a thought came to him and he doubled back.

‘This guy is headed for Bowne Park, you gotta figure the area’s familiar to him. Maybe he was going that way the day of the kidnapping, so he could have headed east across 42nd Street to the FDR. I used to work at the 17th and if your guy ran a red light, there’s a camera at 42nd and 2nd might have given him a Kodak moment. You could check with the D.O.T.’

‘Scratch that carriage clock,’ Crane said to the group, winking. ‘Nice one, Nic. We’re on it.’ Old Nic raised a hand as he left. ‘You just want to hug the guy,’ said Crane as he put a call in to the Department of Transportation. Thirty minutes later, he had five hits, three with criminal records. But only one had a prior for attempted kidnapping.

Joe could feel the drugs kick in. A warm cloud of relief moved up his jaw. He opened and closed his mouth. His ears crackled. He breathed through his nose and out slowly through his mouth. Six years ago, everything from his neck up started to go wrong – he got headaches, earaches, pain in his jaw so excruciating that some days it was unbearable to eat or even talk. Strangers didn’t react well to a dumb cop.

Hayley Gray was thinking about Beauty and the Beast. Everyone thought the Beast was mean and scary, but he was really a nice guy and he gave Belle soup and he played in the snow with her. Maybe the man wasn’t all bad. Maybe he’d turn out to be nice too. The car stopped suddenly and she felt cold. She heard her mommy shouting.

‘Hayley! Hayley!’ Then, ‘Where’s my daughter? You’ve got your money. Give me back my daughter, you bastard!’

Her mommy sounded really scared. She’d never heard her shout like that before or say bad words. She was banging on the window. Then the car was moving again, faster this time, and she couldn’t hear her mommy any more. Donald Riggs threw open the knapsack, his right hand pulling at the tightly packed wads.

Danny reached for his radio to run the plates of the brown Chevy Impala that was driving away from Elise Gray: ‘North Homicide to Central.’ He waited for Central to acknowledge, then gave the number: ‘Adam David Larry 4856, A.D.L. 4856.’

Joe was on Citywide One, a two-way channel that linked him to Maller and Holmes and the 109 guys in the park. He spoke quickly and clearly.

‘OK, he’s got the money, but he hasn’t said anything about dropping off the girl. We need to take it easy here. We don’t know where he has her. Everyone stand by.’

Danny turned to him and gave his usual line. ‘And his voice was restored and there was much rejoicing.’

Halfway down 29th Avenue, Donald Riggs stopped the car, reached back and lifted the blanket.

‘Get up and get out of my car.’

Hayley pulled herself onto the seat. ‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘I knew you’d be nice.’

She opened the door, got out and looked around until she could see her mother. Then she ran as fast as her little legs could carry her.

Joe and Danny were behind Riggs now, Agents Maller and Holmes behind them. Danny was holding for the information on the car. Joe was distracted. He had a feeling this was bad; the kind of bad that happens when everything is too easy, when the maniac is so fucked up, it gets scary calm. He looked at Danny.

‘Why would the guy give this woman her child back without a scratch?’ He shook his head. ‘It’s too easy.’

He slammed on the brakes and, arm out the window, waved the Crown Vic ahead of him. Agent Maller gave a quick nod and took the right, eyes locked on the car ahead.

Joe turned around and saw the swaying shape of a mother and daughter reunited. Too easy. He got out of the car, grabbing his vibrating cell phone from the dash. He flipped it open. It was Crane.

‘We got your perp.’

‘Brown Chevy Impala,’ said Joe.

‘Yup, ’85. Riggs, Donald, white male, thirty-four, born in Shitsville, Texas, locked up for petty larceny, scams, bad cheques, collared at the scene of a previous kidnapping.’ He hesitated.

‘And be advised, Lucchesi, he was done for C4 in Nevada in ’97. We got ourselves a boom-boom banjo-player.’ Joe dropped the phone, his heart pounding.

‘I got ESU and hostage negotiation on stand-by,’ Crane said to no-one.

Joe began to run. He willed his heart to carry the new pace his legs had taken up.

Donald Riggs had reached the corner of 154th and 29th. He rocked back and forth in his seat, skinny fingers clenching the wheel, eyes darting around, taking in everything, registering nothing. But something caught his eye. Behind him, a black Ford Taurus pulled into the kerb and a dark blue Crown Vic overtook it. A rare heightened awareness flared inside him. He kept driving, his breath shallow as he slowed to a stop at the next corner. Then a sudden burst of activity drew him in. Two men stepped out of a Con Ed van by the entrance to the park. They walked quickly to the back and pulled open the doors. Two others stepped out. In the rear-view mirror, the dark blue car loomed back into sight, driving alarmingly on the wrong side of the road. Donald Riggs lurched across the passenger side, grabbed the knapsack, pushed open the door and tore out of the car towards the park. By the time Maller and Holmes screeched to a stop seconds later, the four FBI agents in Con Ed uniforms were surrounding an empty car. ‘Go, go, go!’ roared Maller and all six men ran for the park.

‘You used my pager!’ says Hayley, amazed, pointing down at the belt around her waist and the black box with its flashing yellow light. Her mother stands up, confused, searching out anyone who can understand what this is, but knowing in her heart the answer. Her pleading eyes stop at Joe.

‘You stupid bitch, you stupid bitch, you stupid bitch …’ Donald Riggs is running wildly across the park, clutching at his knapsack, concentrating on a small dark object in his hand. He stops, rooted. His eyes widen and deaden as his mind and body shut down. Then a twitching afterthought of a movement connects the thumb of his right hand to the black button of a detonator.

Elise Gray knows her fate. She makes a final grab for her child, hugging her desperately to her chest. ‘I love you, sweetheart, I love you, sweetheart, I love you.’ Then a frightening, shockingly loud blast tears through them, the bright light stinging Joe’s eyes as he watches, now motionless. Then red and pink and white, splattering grotesquely, as a confetti shower of leaves and splintered bark falls around the place where a mother and daughter, seconds earlier, didn’t even make it to goodbye.

Joe was absolutely still, paralysed. He couldn’t breathe. He felt a new throbbing pressure in his jaw. His eyes streamed. He slowly sensed warm concrete against his face. He pulled himself up from the pavement. Too many emotions flooded his body. The radio on his belt crackled to life. It was Maller.

‘We lost him. He’s in the park, heading your way, along by the playground.’

Now one emotion overrode all others: rage.

‘I don’t think your mommy was a good girl, Hayley, I don’t think your mommy was a good girl,’ Riggs was howling, ranting, rocking wildly, bent over, his face contorted. He clawed desperately at the inside pocket of his coat. Joe burst through the trees, suddenly faced with this deranged display, but ready, his Glock 9mm drawn.

‘Put your hands where I can see them.’

He couldn’t remember his name. Riggs looked up; his arm jerked free, swinging wildly to his right and back again, as Joe pumped six bullets into his chest. Riggs fell backwards, landing to stare sightless at the sky, arms outstretched, palms open. Joe walked over, looking for a weapon he knew did not exist.

But something did lie in Riggs’ upturned palm – a maroon- and-gold pin: a hawk, wings aloft, beak pointing earthwards. He had been gripping it so tightly, it had pierced his palm.

Ely State Prison, Nevada, two days later

‘Shut up, you fuckin’ freak. Shut your fuckin’ ass. I got National Geographic in my fuckin’ ears twenty-four/seven, you sick son of a bitch. Who gives a shit about your fuckin’ birds, Pukey Dukey? Who gives a fuckin’ shit?’

Duke Rawlins lay face down on the bottom bunk of his eight-by-ten cell. Every muscle in his long, wiry body tensed.

‘Don’t call me that.’ His face was set into a frown, his lips pale and full. He rubbed his head, disturbing the dirty-blond hair that grew long at the back, but was cut short above his chill-blue eyes.

‘Call you what?’ said Kane. ‘Pukey Dukey?’

Duke hated group. They made him say shit that was nobody’s business. He couldn’t believe this asshole, Kane, knew what the kids used to call him in school.

‘This hawk has that wing span, this hawk ripped a jack rabbit a new asshole, this hawk is alpha, this hawk is beta, and this little hawk goes wee, wee, wee, all the way home to you, you sick son of a bitch.’

Duke leapt from his bunk, sliding his arm from under the pillow, pulling out a pared-down, sharpened spike of Plexiglas. He jabbed it towards Kane, who jerked his head back hard against the wall. He jabbed again and again, slicing the air close enough to Kane’s face to let him know he meant it.

The warden’s voice stopped him.

‘Lookin’ to book yourself a one-way ticket to Carson City, Rawlins?’ Carson City was where Ely’s death-row inmates took their last breath.

Duke spun around as he unlocked the door and pushed into the cell. The warden smoothed on a surgical glove and calmly took the weapon from a man he knew was too smart to screw up this close to his release.

‘Thought you might like to read this, Rawlins,’ he said, holding up a printout from the New York Times website.

Duke walked slowly towards the warden and stopped. The pockmarked face of Donald Riggs jumped right at him. KIDNAP ENDS IN FATAL EXPLOSION. Mother and daughter dead. Kidnapper fatally wounded. Duke went white. He reached out for the paper, pulling it from the warden’s hand as his legs slid from under him and he slumped on to the floor. ‘Not Donnie, not Donnie, not Donnie,’ he screamed over and over in his head. Before he passed out, his body suddenly heaved and he threw up all over the floor, spraying the warden’s shoes and pants.

Kane jumped down from his bed, kicking Duke in the gut because he could. His laugh was deep and satisfied. ‘Pukey fuckin’ Dukey. Man, this is quality viewing.’

‘Get back to your business, Kane,’ said the warden as he turned his back on the stinking cell.