скачать книгу бесплатно

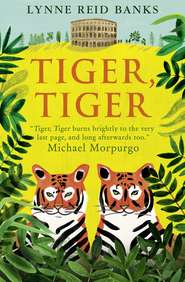

‘But they look so sweet, like big kittens—’

‘Do you need to lose half your hand to find out that they’re not? They’re for the arena, they have to be fierce.’

The cubs watched warily as the other captives were lowered to the ground near them, and soon the crowd had moved away to inspect the bears, the peacocks, the monkeys. When the she-elephant was carefully lowered from above, there were gasps and shouts.

‘Great gods!What a size! Keep clear of it!’

‘Will the Emperor show it at the Colosseum? Will they bait it, like the bears, with dogs?’

‘Perhaps. I hope so! What a fabulous show that would be!’

‘How many dogs will it take to kill a thing that size?’

‘No, Caesar won’t have it baited or killed. They never kill the elephants. Perhaps he’ll ride on it. Think of that! Our great Emperor on the tallest beast in the world, riding along the Appian Way! What a triumph!’

Thick vines were joined to the cubs’ prison and by them it was dragged on to the back of some unalive thing that nonetheless moved. It was pulled by animals whose feet made a hard, clattering sound against the ground. The cubs looked about them. There was sunlight, but not filtered through greenery. It flooded unhindered over green and yellow stretches of ground. The tigers had never left the jungle, never seen fields and crops, and these puzzled them, but at least it was natural earth and growing things – they could smell them and they longed to be free to bound away and seek safety and a hiding place. Freedom was something they had not forgotten.

Behind them came the other captives, dragged along like them. The bears, on their hind legs, held the prison-trees and roared at the crowd. The jackals pawed and whined. The monkeys leapt about, twisting their heads and gazing here and there with their little bright eyes. The two surviving dogs lay licking their wounds. The elephant stood swaying on her huge feet.

The motion went on for a long time. After a while, the cubs grew tired and lay down and slept.

When they woke up, they saw that the natural scenes had gone. Now they could understand nothing of what they saw. They were moving among many two-legs and behind these were big cliffs of stone that had caves in them where two-legs were passing in and out, or standing in the higher ones, looking out. Their interesting but nose-wrinkling smell and the noise of their mouths were everywhere.

The cubs dangled their tongues and let the scent of warm edible flesh enter their noses.

Chapter Two (#u335b149e-861e-5898-9a94-878a9a885f2d)

CAESAR’S DAUGHTER (#u335b149e-861e-5898-9a94-878a9a885f2d)

The Lady Aurelia was reclining on a couch on the balcony of her bedroom. She was twelve years old but already so beautiful and womanly that her father, the Emperor, had issued a protective edict that no man might be alone in her presence without his express permission. The balcony overlooked the palace gardens, and beyond them, three of Rome’s fabled ‘seven hills’ could be seen, covered with a mixture of sun-bleached stone buildings and cypress trees, their stately dark fingers wagging at the sky as if admonishing the gods for not giving Aurelia enough to do.

Her mother had hinted again, only that morning, that Aurelia was indulging in too much idleness and daydreaming. As a Roman emperor’s daughter she already had some duties, but they were not of a kind to alleviate the boredom she felt in doing them or in looking ahead to doing them again tomorrow. She had her regular lessons, of course, but only the musical ones actually engaged her, and that was as much because of the charms of her music teacher, a young Assyrian with coal-black curly hair and nervous but excited eyes, as for any fascination with the lute. Her other tutors were old and deadly dull, and didn’t seem to realise that she was quicker-witted than they were, and usually grasped what they were mumbling at her long before they’d got to the end of their meandering sentences.

Aurelia had all the intelligence that her clever parents could bequeath her. But it seemed it wasn’t going to do her much good.

Of course, her looks would do her good, if being helped to a rich husband was considered good. The son of a senator, perhaps, or an officer in the Praetorian Guard. She was aware that her mother was already on the lookout for a suitable match, though she would not be expected to marry until she was thirteen, or even fourteen if she were lucky.

She sighed from her very depths. Other young girls – the few her parents considered suitable for her to associate with – seemed to talk and think of little but beautiful young men and marriage, but the idea of following in her mother’s footsteps – marriage at thirteen, motherhood a year later, a life of matronly duties and domesticity – appealed toAurelia about as strongly as being tied up in the arena and fed to the wild beasts, like those strange, death-inviting Christians.

No, no. Of course not, not that. Aurelia stopped sighing and shuddered. She turned her mind away, accompanying the mental trick with a swift quarter-turn of her head. She had learnt early how to swamp ugly imaginings with pleasant ones.

‘I am so lucky, not to be a Christian,’ she said aloud. This was part of the ritual of drowning fearful or unpleasant thoughts.

She was lucky. She had grown up knowing that she was. This was part of her cleverness, because others in her fortunate situation might have taken it entirely for granted, and not bothered comparing themselves with others. But from her earliest childhood Aurelia had observed the difference between the way she lived and the way the common people of Rome lived, in their several social layers, right to the bottom where there were slaves and the poor. It was a very great difference, and she pondered it every time she left the palace.

Even inside it, the palace servants, though relatively comfortable, led lives of terrifying insecurity. Once, five years ago, she had seen one of her own handmaids cruelly flogged. It had happened as a direct result of Aurelia complaining about her for some trifle. When a young child witnesses such a thing and knows herself to be the cause, she learns some lessons. The simplest would be to harden her heart. That’s what others did. But Aurelia learnt something better – to control her temper and to deal with her servants herself.

But she had learnt something more from hearing her maid’s screams. She had found out her place in the world, that she had power, and that her father had much more – almost an infinite amount. Later she grasped something of what power means. What she didn’t yet understand was why some have it and others lie under its lash. If her tutors could have taught her that, she would have listened to them with all her attention. But when she asked them, they seemed not only unwilling, but unable to answer. Some of her questions scandalised them.

‘All societies have hierarchies,’ she was told. ‘All societies have higher and lower, masters and slaves.’

‘It must be terrible to be a slave!’

‘You must not entertain such thoughts. Waste no pity on slaves. They have no responsibilities, no traditions to maintain, no laws to make and keep. They have no concerns about food and shelter. They only have to do what they’re told, and live out their simple lives in peace and order.’

‘And the animals?’

‘What animals?’

‘For example, the animals in the arena that are set to fight the gladiators, and each other. They’re usually killed in the end, and they’ve done no wrong. Why do they have to be hurt?’

Her teacher stared at her.

‘Why does any living being suffer? It is all the will of the gods. It is their design. It is blasphemy to question the order of nature. Surely you’re not questioning your father’s right to show the people signs of his power, to entertain them with circuses?’

Aurelia was silent. But on another occasion, she asked: ‘What is Christianity? Why is it so dangerous that people are killed for it?’

This time her tutor threw up his hands. ‘Don’t you know that Christians don’t believe in our gods – that they’ve set up a single, all-powerful god above ours? Could any heresy be worse? Come, enough of this idle tongue-wagging! You must stop asking foolish questions and get down to the study of the heavens.’ He wagged a finger at her. ‘Sometimes it is hard not to suspect you of harbouring heretical thoughts.’

Heretical thoughts. Thoughts outside what was permitted.

Aurelia knew she had many such thoughts and questions. With good reason this simple fact terrified her, and she tried to suppress them. Even being Caesar’s daughter would not save her from some dreadful punishment if it was believed she criticised him, even in the privacy of her heart.

*

Now she rose languidly and walked slowly through the heat to the fountain in the centre of the courtyard of her apartment. Its constant music and the cooler air around it always soothed her. In the pool at the fountain’s foot there were water lilies, and in their shadow exotic fish, brought from afar. She crouched beside the parapet and trailed her hot hand in the limpid water, letting the tinkle and splash of the fountain make her mind a harmless blank.

A large orange-coloured fish came to nose her fingers inquisitively.

She did her trick, something she’d discovered for herself. She let her fingers move gently in the water, and the fish glided in between them and held itself there with lazy motions of its tail while she very delicately stroked its slippery sides. She concentrated intently. She knew that if she moved her hand quickly enough she could stick her forefinger and thumb into the fish’s gills and, in a swift movement, lift it out of the water. She could capture it and end its life if she chose to. She knew this because she’d done it once, held a trapped fish firmly out of the water, felt it struggling in her hands, felt its struggles cease… Afterwards she’d felt sick. She’d thrown the dead thing back in the pond, where it turned on its side and floated until a servant came and cleared it away.

Now she tickled the fish for a few minutes and then lifted her hand suddenly and watched it flash away amid the bright drops from her fingers.

That was power. To have a life in your hand. Even a fish’s. She felt the thrill of it. But something told her it was an evil power – to kill because you could, without reason, for pleasure. She felt dimly that the true power was to withhold the death-stroke, to let the creature go when you could have killed it.

Such deep thoughts tired her. She sighed and went back to her day bed.

She had hardly settled on it when one of her maids came soft-footedly across the marble tiles to her side. She was breathing fast and her face was flushed.

‘My lady, someone is here to see you. He – he has brought a gift.’ She looked strange, as if she were torn between hysterical laughter, and fear.

Aurelia sat up sharply.

‘Who is it?’

‘I don’t know. But he says your honourable father sent him.’

‘Well, send him in!’

‘No – no, I can’t, my lady! You must come out and see what he’s brought. He can’t bring it in here!’ She let out a high-pitched giggle of excitement.

Aurelia pulled the girl down beside her. ‘Tell me,’ she said. ‘Tell me at once what it is.’

‘It’s – it’s a…’

‘Yes, go on! What’s the matter with you?’

‘It’s a tiger, my lady!’

Aurelia was silent for a moment, puzzled.

‘You mean, a tiger-skin rug.’

‘No.’

‘A stuffed tiger.’

‘No, my lady! A real, live one! Oh, please come and see it!’

Aurelia pushed her away, threw her long dark curling hair back over her shoulders, and stood up. Her heart was throbbing behind her ribs. A real, live tiger? But that was impossible! Of all the beasts brought from far-off countries to please the crowds with their ferocity, the tiger was one of the most formidable. Also, because it came, not from Africa, but from some far eastern land, it was the rarest, and most terrible, somehow. There could be no one bold enough to introduce one into Caesar’s palace! But the girl had said Aurelia’s father had sent it. As a gift.

She ran swiftly across the cool floor to the double doorway and flung the doors open.

There it was, indeed. Safely in a cage on wheels. And very young. And very, very – oh, there were no words for what it was! Beautiful, sweet, adorable. Fabulous.

Aurelia didn’t even notice the person who had brought it. She crouched down, a safe distance from the cage, and stared into the yellow eyes of the cub.

‘Hello,’ she breathed.

The cub stared back for about five seconds. Then it turned its face aside.

One paw, seemingly too large for its body, stuck through the bars of its cage. Not the whole paw, of course – the bars were too close together. Just the tip of it. Aurelia, greatly daring, crept forward and touched the golden fur with one finger. The cub pulled the paw back and then swiped the bars of the cage. Aurelia saw its claws spread themselves and jerked her hand away.

‘He wants to scratch me!’

‘It’s his instinct, Princess. But don’t fear. His claws will be seen to.’

She looked up swiftly. He was young and brown with smooth, round, muscled arms. A slave from the menagerie. He wore an animal skin over his tunic as a sign of his profession.

‘‘Seen to’? How, seen to?’

‘His claws will be drawn.’

She frowned. ‘What do you mean, drawn?’

‘Pulled out, Princess.’

For a second she felt faint. She clenched her hands as a sympathetic pain struck her fingernails.

‘You mean – someone will pull out all his claws?’

‘Of course. You couldn’t play with him if he had sharp claws.’

‘How? How will they do it?’

‘You need not trouble yourself—’

She raised her voice to one of command. ‘Tell me immediately how they will… draw his claws?’

‘With pliers, my lady. They will pull them out as teeth are pulled out.’

She stood up. ‘You will not do that to him. You will cut his claws instead, the way my finger and toenails are cut by my maid, straight across so they have no sharp points.’

‘He could still—’

‘There is no more to be said. He is to be mine, isn’t that so? I will say what shall be done with him.’

The young keeper bowed his head. But still, he muttered something.

‘Speak louder!’

‘I said, Princess, that you may keep him in his cage, just as he is, but if you want to let him out and play with him, you must let us protect you. He’s only a baby now, but like a cat he can already bite and scratch.’ He showed her several deep red scratches on his arm. She drew in her breath. ‘And when he grows a little bigger he may be dangerous to you unless you let us draw his claws. His fangs,’ he added boldly, ‘have already been removed.’

‘What!’ she shouted. ‘You’ve started pulling his teeth out too! How will he eat?’

‘Our concern,’ said the youth, with a touch of humour, ‘is that he shall not eat you.’

She looked back at the cub. He was looking at her again.

‘Will he try to bite me if I put my hand into his cage?’

‘No. I have handled him and gentled him. Also he’s not feeling very fierce just now because of the long journey he’s had, and the operation. Do you like him?’

‘Oh, yes,’ she breathed, gazing at the fabulous creature. Her own. Her very own. She glanced again at the scratches on the young man’s smooth, brown arm, and quailed for a moment. But then she stiffened herself. Cautiously she stretched her small hand, sideways to be narrow enough, between two bars towards the animal’s bicoloured head. Its ears moved, flattened. It growled deep in its throat. She snatched her hand out again.

The young keeper laughed. He unfastened the lid at the top of the cage and raised it. Then he reached in fearlessly and scratched the cub behind the ears. It looked up at him trustingly.

‘How can he like you and trust you when you’ve hurt him? It must have hurt terribly to have his fangs pulled out!’

‘I didn’t do it, Princess. I was the one who comforted him afterwards, rubbed oil of cloves on the wounds and gave him warm milk in a bottle to remind him of his mother.’

‘Where is she?’

‘Who knows? Far away in the jungle he came from. He won’t see her again.’ He was petting and stroking the tiger’s head, working his hand under its jaw. The cub’s eyes closed in bliss. There was a different sound from him now – a rumble of pleasure.

Aurelia stood up. ‘Oh, let me! Only I don’t want him to growl at me.’

‘He won’t. Here, take over from me. He’ll soon learn to accept you.’