скачать книгу бесплатно

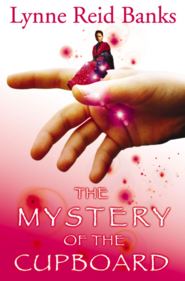

The Mystery of the Cupboard

Lynne Reid Banks

What will Omri find inside the eaves of his new home? Will there be more little figures that come to life?After Omri reads his great-great-great-aunt’s account, he longs to try the key. And when his friend Patrick comes to stay, nothing can stop him…

For my family.

Contents

Cover (#u2bda937d-774a-50a1-a48b-50c1b24b6546)

Title Page (#u64c743ac-4536-5ea7-9c5a-6b3e9645cdbd)

1. The Longhouse (#u2fa2c6e7-678c-5f66-ae46-dc8ae9f400b2)

2. Kitsa Goes Missing (#u12a9ab0c-55ba-5e75-ae37-7c4482ddc61e)

3. Hidden in the Thatch (#ufe764044-c2aa-5f4d-9e64-ed88674c0f78)

4. Jessica Charlotte’s Notebook (#u5765b4ed-240b-51d2-a025-8530270963d0)

5. Family Stuff (#uc074ecab-e8ca-50b0-95d2-9be8a336de22)

6. Pouring the Lead (#litres_trial_promo)

7. The Day of the Parade (#litres_trial_promo)

8. The Old Bottle (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Frederick (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Patrick (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Tom (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Jenny (#litres_trial_promo)

13. The Fall (#litres_trial_promo)

14. The Cupboard (#litres_trial_promo)

15. In the Cashbox (#litres_trial_promo)

16. The Jewel Case (#litres_trial_promo)

17. A Sudden Emergency (#litres_trial_promo)

18. The Sleeping Lady (#litres_trial_promo)

19. Maria’s Bequest (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue: A Funeral – and After (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#ulink_a4f8f49b-93be-5b11-9e0b-ec5c14938b07)

The Longhouse (#ulink_a4f8f49b-93be-5b11-9e0b-ec5c14938b07)

“But Mum, I don’t want to move house again!”

Omri’s mother stared at him with her mouth slightly ajar. She turned away for a moment as if she simply couldn’t think of a thing to say, and then swiftly turned back.

“Omri, you know what, you’re incredible. Ever since we moved here you’ve done nothing but moan. You hated the district, you hated the street, you hated the house—”

“I never said I hated the house! I like the house. I love the garden. Anyway, even if I did hate it, I wouldn’t want to move. All that packing and general hassle last time, it was awful! Why do we have to move again?”

“Listen, darling. You remember the freak storm?”

Omri stared at her. Remember it? Could anyone who’d survived it possibly ever forget it?

“Stupid me, of course you do, I only meant— well, it wrecked the greenhouse—”

“It wrecked my room—”

“The chimney fell off, the roof had to be—”

“But Mum, that was all months ago. It’s all been mended, pretty well.”

“At vast cost,” put in his father, who was sitting at the breakfast-room table writing out a description of their house. It was coming home unexpectedly early and catching his father on the phone to an estate agent that had tipped Omri off that his parents were thinking about selling and moving.

“Yes, and now with a new roof and everything, it’s a good time to sell. Besides, Dad really hates living in town.”

Now it was Omri’s turn to have his mouth hanging open.

“You mean we’re not going to live in London?”

“No. We’re going to live in the country.”

Omri sat up sharply. “The country!” he almost shouted, as dismayed as if his father had announced they were going to live at the bottom of the sea.

“Yes, dear, the country,” said his mother. “That big green place with all the trees - you know, you’ve seen it through the car window when we’ve been racing from one hideous town to another.”

Omri ignored her sarcasm. “Would it be Kent?” His best friend, Patrick, lived in Kent.

“No.”

That put the lid on any thoughts that it might not be so bad.

“But - but - are we just moving because of Dad?”

“Certainly not,” his father said promptly. “We’re also moving because the local high school, which your brothers already go to and which you will, in theory, be starting at in September, is a sink. It’s enough that two of my sons come home two days out of five looking as if they’ve fallen under a bus. It’s enough that Gillon’s marks are in steady decline. I’m not going to compound my mistake by sending you there too.”

But Omri had stopped listening and was halfway to the door.

“Do Adiel and Gillon know?”

“We were going to have a family conference tonight after supper. Only you wrung it out of me,” said his father. “And you don’t have to go telling them straight away—”

But Omri was already charging up the stairs. At the top he burst into the first room he came to, which was Gillon’s.

“We’re going to live in the country!” he exploded.

Gillon, who had jumped up guiltily from his bed (where he’d been lying reading a magazine instead of doing homework) because he thought it was a parent, slumped back again and stared at Omri, stunned.

“The country!” he repeated in exactly the same tone as Omri had used. “We can’t be! What’ll we do there? There’s nothing to do in the country, we’ll be bored out of our minds!”

But Omri had already vanished and was beating on Adiel’s door. Adiel really was doing homework, and had locked his door to keep out intruders.

“Get lost!” he yelled from his desk.

“Ad, listen! Dad’s just told me. We’re going to live in the country!”

There was a pause, then the bolt was drawn, the door opened, and Adiel’s face appeared. He stared at Omri in silence for a few seconds.

“Good,” he said maddeningly, and shut the door in his face.

“Are you crazy?” Omri called through the door. Gillon had come out and was standing next to him.

“He said ‘good’!” Omri told him indignantly.

“Ask him if he’s crazy.”

“I just have!”

“Are you crazy?” Gillon shouted at the top of his voice through the door.

“Boys, stop that row, that’s enough! Come down and we’ll talk about it!” came their father’s irritated voice from the foot of the stairs.

Omri and Gillon trailed down and back into the breakfast room. After a few minutes, Adiel, looking studiedly unconcerned, joined them.

“Now then. Listen first, then blow your tops, okay? This house, due to a fluke in the housing market, is suddenly worth a lot of money.”

“How much?” said Gillon, for whom money was the most important thing in life.

“A lot more than we paid for it. Just because it’s in London and lots of people, whom I can only regard as totally insane, want to live in London.”

“And at the precise moment when we were thinking of selling anyway,” put in their mother eagerly, “something really wonderful has happened. I’ve inherited a lovely house.”

“Inherited? Does that mean we get it for nothing?”

“Yes! Isn’t it incredible?”

“But what’s it like? Have you seen it?”

“Well, er - no, not yet. But it sounds beautiful. Not as big as this one—”

“WHAT!” all the boys - even Adiel - yelled in chorus.

“But that won’t matter,” put in their father quickly, “because we will not be surrounded on all sides by this stinking, overcrowded, crime-ridden city where you can’t snatch a breath of clean air or walk ten yards without being mugged—”

“Lionel, there’s no need to exaggerate, none of us has ever been mugged—”

“—Or at least tripping over litter, and we will live in peace and safety and beauty, in a much nicer, if somewhat smaller, house with much more land, and we’ll have a better life. Now what on this polluted earth, may I ask, is wrong with that?”

Silence. Then Adiel said, “Sounds okay to me. Only where would we go to school?”

Their father and mother gave each other a little married look. Their father cleared his throat and said, “Well. What would you say to boarding?”

He was looking only at Adiel when he said it, and Adiel didn’t flinch. But Gillon gave a great screech and fell off his chair onto the floor, where he lay spread-eagled and twitching.

“Oh, get up,” said his mother, hauling on one arm. “You clown. He didn’t mean you.”

Gillon sat up sharply.

“He didn’t? Why not? Aren’t I good enough to go to boarding school?”

“No,” said Adiel. “At boarding school you’re not only expected to work, you have to keep your room tidy. You’d be kicked out in a week.”

Gillon uttered a short word under his breath and slumped back onto the floor. From there he said, “I suppose we couldn’t have a dog.”

“A dog!” exclaimed Omri. “What about Kitsa?” Kitsa was his cat.

“It would eat her,” said Gillon cheerfully. “Bit of a laugh, eh?” He sat up again. “It’d be good, we might get a rottweiler and then it would eat you, too.”

“What we might actually get,” remarked their mother, “is a pony.”

The boys all looked at one another in bewilderment. None of them had ever shown the faintest interest in riding. Only for Omri did the idea of a horse have any associations. But they were very pleasant ones.

He said slowly, “That might be all right. I wouldn’t mind that.”

“Are you crazy? You’ve never even sat on a horse!” said Gillon.

“I’d like to, though,” said Omri.