Полная версия:

The Bitter Sea: The Struggle for Mastery in the Mediterranean 1935–1949

THE BITTER SEA

The Struggle for Mastery in the Mediterranean, 1935–1949

SIMON BALL

To Helen

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Maps

Introduction

1 The Dead Dog

2 Death on the Nile

3 Of Mice and Men

4 Gog & Magog

5 Mediterranean Eden

6 Losing the Light

7 Italy Victorious

8 The Last Summer

9 Of Worms and Frenchmen

10 The Deceivers

11 The Good Italians

12 The Last Supper

13 Mission Impossible

14 Goodbye Mediterranean

Conclusion

Notes and References

Index

Sources and Acknowledgements

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher

MAPS

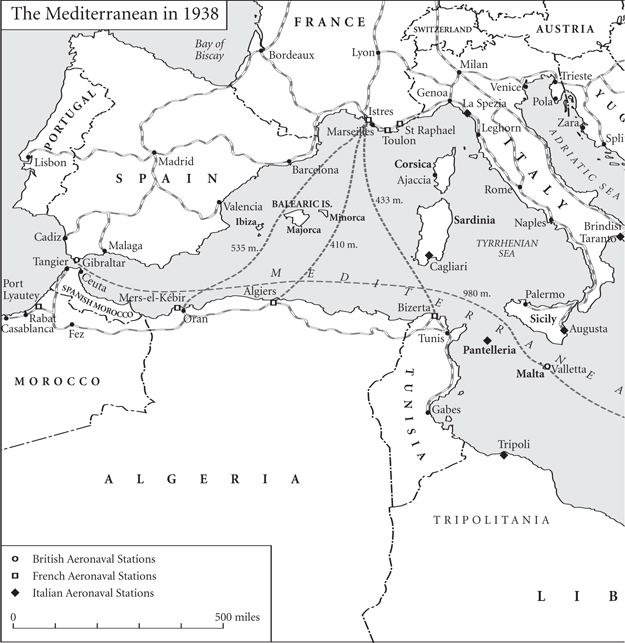

Map 1 The Mediterranean in 1938

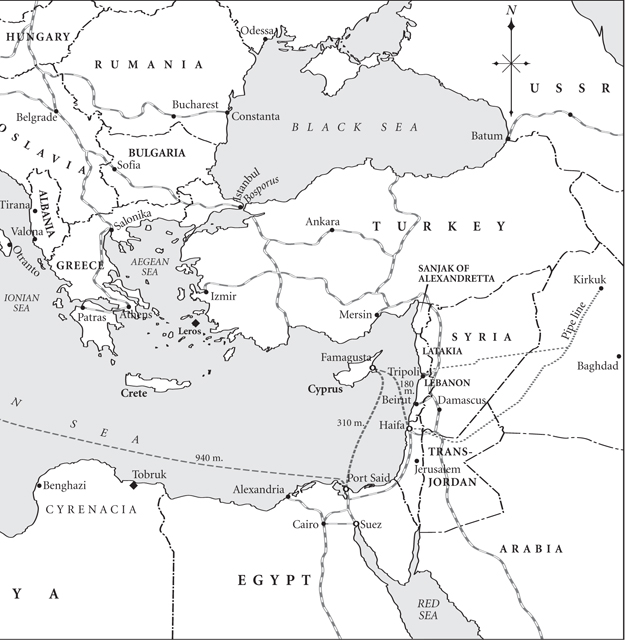

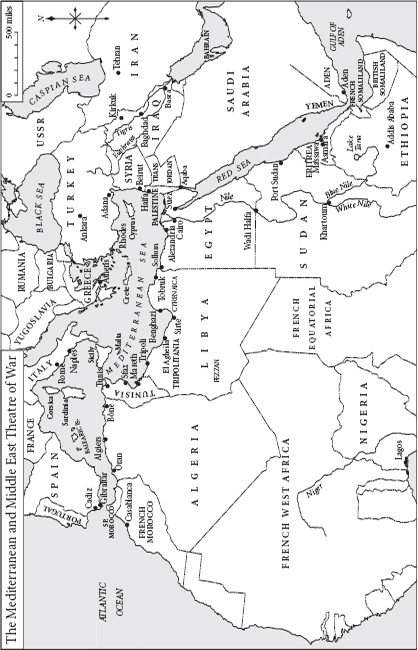

Map 2 The Mediterranean and Middle East Theatre of War

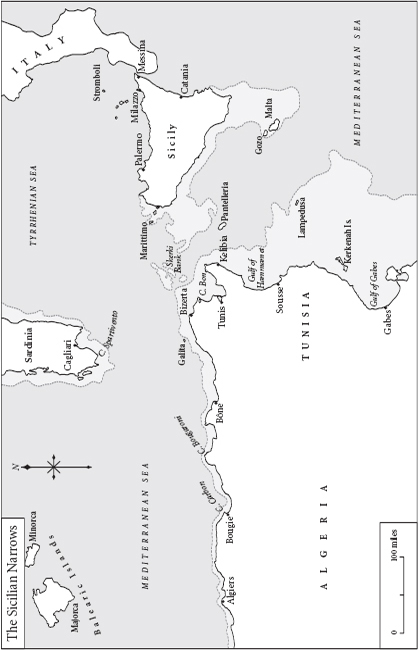

Map 3 The Sicilian Narrows

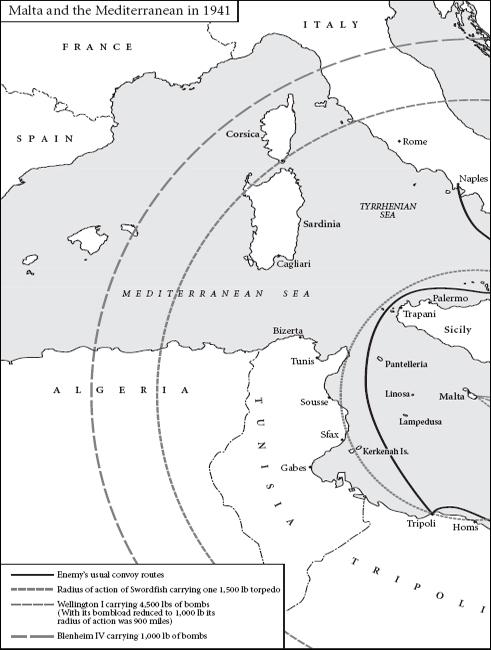

Map 4 Malta and the Mediterranean in 1941

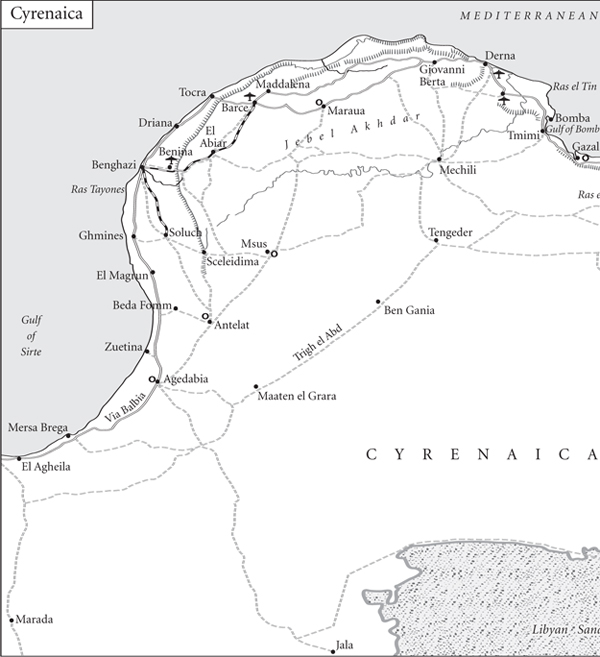

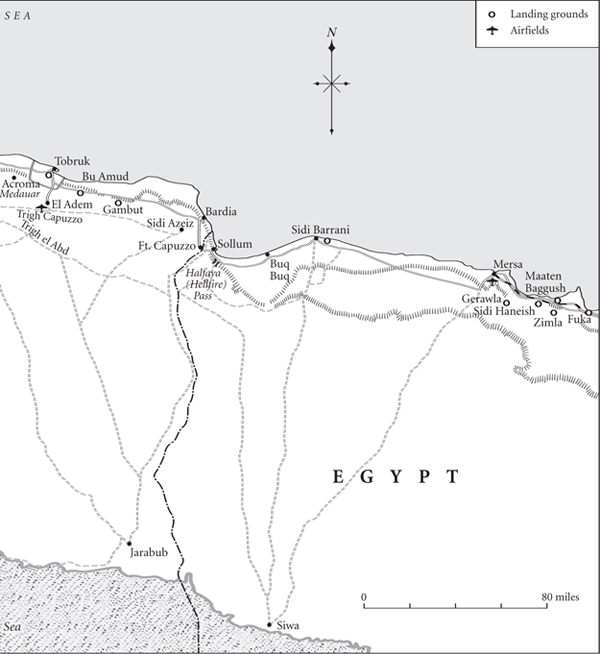

Map 5 Cyrenaica

Map 6 Greece and the Aegean

Map 7 The Partition of Yugoslavia in 1941

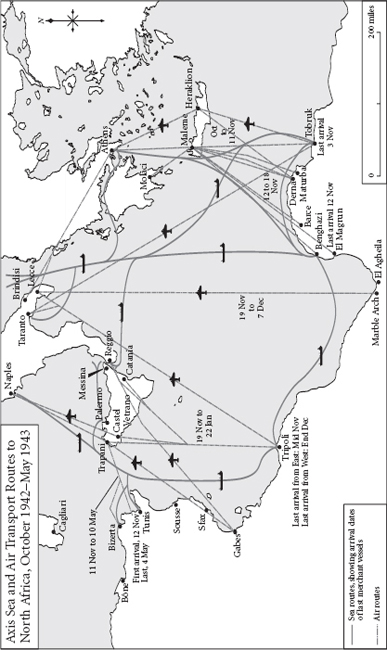

Map 8 Axis Sea and Air Transport Routes to North Africa, October 1942–May 1943

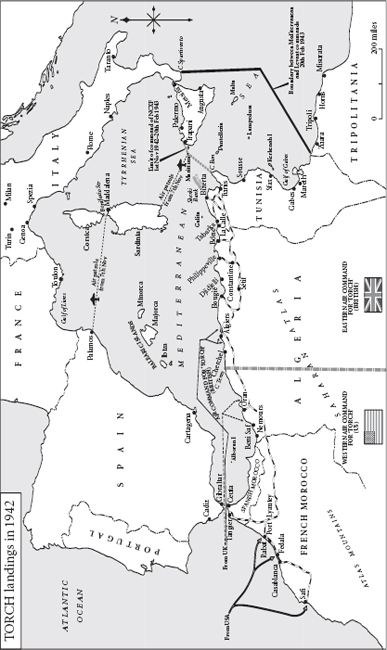

Map 9 TORCH landings in 1942

Map 10 Italy showing German defensive lines with dates of their fall

INTRODUCTION

In July 2008 the Libyan tyrant Muammar Gaddafi announced that he would boycott the inaugural meeting of the Union for the Mediterranean, or ‘Club Med’ as it was invariably known. The President of France, Nicolas Sarkozy, had summoned forty-two Mediterranean leaders to Paris to create the Union. Newly elected, he wanted an alternative to the faltering ‘Barcelona process’ that, since 1995, had been a vehicle for transferring aid from the European Union to the Arab world. Something grander and more heroic was required to capture the imagination of Europe and the Middle East, Sarkozy believed. Gaddafi was appalled. The initial invitation to Club Med, issued in December 2007, was grandly entitled, in the worst possible taste, the ‘Appeal from Rome’. Libya had been created from the ashes of Mussolini’s Roman Empire. Sarkozy had flanked himself with the leaders of Spain and Italy, an echo of the unrealized Mediterranean Axis of 1940. ‘We shall have another Roman Empire and imperialist design,’ Gaddafi snarled from his palace in Tripoli. ‘There are imperialist maps and designs we have already rolled up. We should not have them again.’ 1

This is a book about an idea and its time. The idea was that there was a place called the Mediterranean and that the Mediterranean was worth fighting for. The time was the mid-1930s to the late 1940s.

The existence of the Mediterranean is embedded in the modern imagination. 2 Long before the aeroplane or the satellite created aerial pictures of the Mediterranean, the Victorian art critic John Ruskin urged his reader to rise with him higher than the birds. Together they would see ‘the Mediterranean lying beneath us like an irregular lake, and all its ancient promontories sleeping in the sun’. Beneath them were ‘Syria and Greece, Italy and Spain, laid like pieces of a golden pavement into the sea blue’. 3 This vision of the ‘golden pavement’ and ‘sea blue’ was endorsed by the most famous twentieth-century history of the Mediterranean. In The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, published in 1949, the French historian Fernand Braudel insisted that the Mediterranean was a unit of ‘creative space’: its amazing freedom of sea-routes and ‘complementary populations’ shaped human actions. Braudel’s putative subject was the sixteenth century, but few were in any doubt that he was addressing his own times. 4 As Braudel himself remarked, his view of the historical Mediterranean was formed by his years as a teacher in Algeria. He imagined a Mediterranean seen from the ‘other bank’, ‘upside down’. 5

Yet there were sceptics about ‘the Mediterranean’. What, writers from Mediterranean countries asked, did all this talk about ‘Mediterranean culture’ amount to, beyond chatter worked up into an intellectual system? The Mediterranean was not a good ‘unit of analysis’. The unity of its populations was illusory. National histories mattered more than an ill-defined Mediterranean identity. 6 The Mediterranean did not make much sense. A central tenet of ‘Mediterraneanness’ was that religious difference, though not religions, was essentially unimportant. As Braudel put it, the Islamic Mediterranean lived and breathed with the same rhythms as the Christian. Yet at the very moment he wrote, the whole concept of the ‘the Middle East’, a different, identifiable, Muslim, world incorporating eastern Mediterranean lands, had colonized the imagination of politicians and journalists. Efforts to halt or reverse the spread of the concept proved fruitless. Winston Churchill told cavillers: ‘a million or so Englishmen had fought, and many died, in what they knew as the Middle East, and the Middle East it was to remain!’ By the late 1940s the term Middle East was in universal circulation, and has retained its grip ever since. 7

One group able to write about the Mediterranean and the Middle East, without worrying too much about questions of identity, has been military historians. 8 For them the Mediterranean was not a culture area but a theatre. Rather than doubt the self-evident existence of the Mediterranean ‘theatre’, they instead gnawed away at the question of whether the Mediterranean was important to the outcome of the Second World War. The argument stretched back to Anglo-American disputes about strategy in the middle years of the war. 9 These arguments did not long remain private. Elliot Roosevelt, the officer in charge of the air-force photographic reconnaissance in the Mediterranean, but more prominently the son of the President of the USA, published a bilious caricature of foolish British Mediterraneanists and wise American Europeanists as early as 1946. 10 More in the same vein was to follow. The Americans claimed that arms and men had been wasted on a sideshow. The British retorted that American foot-dragging had prevented the exploitation of victory. The burgeoning literature on ‘total’ war dismissed the Mediterranean war as ‘second class’ because of its political and limited nature. ‘Mediterraneanists’ were left to argue that their theatre was of primary importance for short, but pivotal, periods. 11

This book does not assume that the unity of the Mediterranean rested on deep structures. Rather it suggests that any such unity was fleeting. The Mediterranean was the product of competing notions of thalassocracy–‘rulership of the sea’. These ideas were ebbing away by the late 1940s. Whilst belief in the Mediterranean existed, however, there were genuine attempts to wield pan-Mediterranean authority. This is a history of the Mediterranean told from the point of view of those who attempted to rule it. Their Mediterranean was a crucible of modernity. The key features of the Mediterranean crisis–shifting coalitions held together by contingent loyalty, information warfare, the projection of air and sea power, civil war and terrorism–remained crucial long after the Mediterranean itself had become a fantasy of western tourist brochures.

ONE

The Dead Dog

Eyeless in Gaza, Aldous Huxley’s 1936 novel, opens with a metaphor for the Mediterranean: the lazy, ripe, sea-girt lands, beloved of travellers, and Mussolini’s hell-hole. Two sunbathers’ eyes are drawn to the west, to ‘a blue Mediterranean bay fringed with pale bone-like rocks and cupped between high hills, green on their lower slopes with vines, grey with olive trees, then pine-dark, earth-red, rock-white or rosy-brown with parched heath’. To the east they observe ‘the vineyards and the olive orchards mounted in terraces of red earth to a crest’. The ‘sunlight fell steep out of flawless sky’, and they dozed, until ‘a faint rustling caressed the half-conscious fringes of their torpor…and became at last a clattering roar that brutally insisted on attention’. Annoyed, they closed their eyes once more, ‘dazzled by the intense blue of the sky’. Suddenly, ‘with a violent but dull and muddy impact the thing struck the flat roof a yard or two from where they were lying’. ‘The drops of a sharply spurted liquid were warm for an instant on their skin, and then, as the breeze swelled up out of the west, startlingly cold.’ ‘In a red pool at their feet lay the almost shapeless carcass of a fox-terrier. The roar of the receding aeroplane had diminished to a raucous hum, and suddenly the ear found itself conscious once again of the shrill rasping of the cicadas.’ Eyeless in Gaza prophesies a Mediterranean war in 1940. 1

Huxley’s aeroplane was indeed an apt metaphor for Italian Fascism. Sowing chaos from the air was central to Mussolini’s regime. 2 Il Duces collected writings and speeches on the subject were published in March 1937. 3 Flying was dynastic aggrandizement for Mussolini. When he took flying lessons in the 1920s he took his sons, Vittorio and Bruno, to the aerodrome. In 1935 the Mussolini clan ‘volunteered’ to fly in the conquest of Abyssinia. Vittorio Mussolini was nineteen, Bruno only seventeen but worthy of bombing Abyssinians. Their cousin, Vito, son of Mussolini’s late brother, went as well. They were chaperoned by Galeazzo Ciano, the husband of Vittorio and Bruno’s sister, Edda. ‘We have carried out a slaughter,’ Ciano boasted. Vittorio’s shadowed autobiography was rushed out in celebration. He admitted to being a little disappointed by his first bombing raid; the Abyssinians’ feeble huts collapsed without any spectacular strewing of rubble. The Mussolini boys were not, however, good pilots: their true love was brothels rather than aerodromes. On their return from the front they lorded it around Rome, raping girls, crashing fast cars and treating the professional head of the Regia Aeronautica, Giuseppe Valle, like a flunkey. 4 Only Ciano stayed the course, returning to Abyssinia for the final victory in the spring of 1936. The fawning Italian press gave his exploits so much coverage that eventually he ordered them reined in lest he become a laughing stock at his golf club. 5 Nevertheless, Ciano, at the age of thirty-three, emerged from Abyssinia as the ‘hero’ of the dynasty. In the summer of 1936 Mussolini not only made him Italian foreign minister but put him in charge of the Fascist project for Mediterranean conquest. 6 Ciano was a monster: vain, corrupt and murderous. Nevertheless, most people liked his ‘winning ways’. 7 He was good-looking and fun to talk to. Ciano had a low, and usually accurate, opinion of his fellow man, Fascist, Nazi or democrat. He had a gift for self-reflection, as well as self-deceit. Both characteristics were reflected in a diary he began to keep, with Mussolini’s blessing, once he had firmly established himself at the foreign ministry.

Mussolini ‘dropped the dog’ on 3 October 1935 when Italy invaded Abyssinia. The Mediterranean may not have been a peaceful place in the decade before 1935: monarchy was overthrown in Spain, but preserved by a military dictatorship in Greece; the French ruthlessly suppressed colonial peoples in Morocco and Syria; terrorists murdered their ethnic enemies in Yugoslavia and Palestine. Its quarrels were, however, parochial. The Mediterranean itself played little part in these struggles beyond that of a means of departure and arrival. It was Mussolini’s challenge to Britain that plunged the Mediterranean as a whole into its fourteen-year crisis.

The British described their Mediterranean as an ‘artery’. 8 Armies and navies made the passage to the East through the artery, raw materials, tin, rubber, tea and, above all, oil, made their way west. On any given day in the mid-1930s the tonnage of British shipping in the Mediterranean was second only to that found in the North Atlantic. The Mediterranean was not, however, Britain’s only arterial route. Many of the same destinations could be reached by sailing the Atlantic–Indian Ocean route around Africa via the Cape of Good Hope. The Mediterranean’s chief attraction was speed. A ship steaming from the Port of London to Bombay would take a full fortnight longer, and travel nearly 4,500 miles more, to reach its destination if it did not pass through the Mediterranean.

The British artery had three main choke points: Gibraltar, Malta and Port Said. The first port of call for a ship entering the Mediterranean was Gibraltar. Seven million tons of commercial shipping called at Gibraltar every year. The Rock, a mere one-and-seven-eighths square miles in area, had been a British possession since the early eighteenth century. It housed a large naval base for the use of the Home Fleet. Nearly a thousand miles to the east, the small island of Malta lay at a point almost equidistant between Gibraltar and the entrance to the Suez Canal at Port Said in Egypt. It also sat astride the narrowest point in the Mediterranean, the Strait of Sicily. Valletta was one of the great harbours of the world, providing the main base of the Mediterranean Fleet, comprising, at the beginning of 1935, five battleships, eight cruisers and an aircraft-carrier. Apart from its strategic importance, the British dominance of Malta irritated Mussolini. In the early 1930s the British started a campaign to encourage the Maltese language to replace Italian in the schools and law courts. 9 Pro-Italian Maltese ‘traitors’ were imprisoned, and Italian diplomats were expelled from the island for indulging in subversion and espionage. Italian was expunged as a legitimate language. 10

A few ships left the main artery at Malta and headed into the northeastern Mediterranean, to the British possession of Cyprus, ‘off the main track of sea communications…unfortified and garrisoned only by native police, together with one company of British troops’. Unlike Gibraltar and Malta, Cyprus had a large land mass capable of supporting a substantial population–nearly 350,000 in 1935. Its coast was dotted with harbours but they were little more than ‘open roadsteads’ or ‘small and silted up’. The only substantial port was Famagusta on the east of the island. In the mid-1930s the British did consider turning Famagusta into a major naval base. 11 In the end they decided that Cyprus was ‘out of the question for the immediate needs of the moment’. A base at Famagusta would have taken over a decade to complete. 12

Most ships did not divert to Cyprus. They travelled on for another thousand miles from Malta. At Port Said they entered the Suez Canal. A great feat of nineteenth-century engineering, the Canal ran for 101 miles through Egypt, providing a single-lane highway, with passing places to accommodate both north-and southbound traffic. A ship would take–on average–fifteen hours to pass through the Canal before debouching into the Red Sea at Port Suez.

Thus for the British the Mediterranean comprised a seamless whole. The sea was a journey from west to east, and the Mediterranean coast comprised the north and south banks of an eastward-flowing river. 13

By the time ‘major combat operations’ in Abyssinia ended on 9 May 1936, the British had been thoroughly spooked. 14 They could no longer ‘despise the Italians and believe they will never dare to put to and face us’, wrote Winston Churchill. ‘Mussolini’s Italy may be quite different to that of the Great War.’ 15 Major-General Robert Haining, the British army officer charged with assessing his Italian opposite numbers, described the campaign as a ‘masterpiece’. ‘There has been a great tendency in this country’, he warned, echoing Churchill, ‘to think that the Italian of today is still the Italian of Caporetto [whereas] the Italian, from what one has seen of him, is a very different individual to what he used to be.’ 16

The British response to the war was characterized by Sir Warren Fisher, the head of the civil service, as feeble. British officials had stood on the dockside at Port Said as Italian troop ships sailed through the Suez Canal carrying, by their estimation, nearly a quarter of a million men. 17 One in five ships that sailed through the Canal in 1936 were Italian. 18 Italy was able to send three hundred tons of poison gas through the Suez Canal on a refrigerated banana boat. Despite attempts to cover up the shipments, the British were well aware of the weapons of mass destruction passing under their noses. Abyssinia was a honeypot for ambitious writers hoping to make a name for themselves. The most famous, subsequently, of these writers, Evelyn Waugh, wrote to the wife of a British cabinet minister: ‘i have got to hate the ethiopians more each day goodness they are lousy & i hope the organmen gas them to buggery’. 19 The ‘organmen’ did Waugh proud. Sir Aldo Castellani, a prominent Harley Street surgeon and father-in-law of the British High Commissioner in Egypt, discredited British reports about gassing by claiming that the photographs of gas victims actually showed lepers. He admitted the truth, in private, to his English friends. 20 ‘No country believes that we ever intended business,’ lamented Sir Warren, ‘and our parade of force in the Eastern Mediterranean, so far as impressing others, has merely made a laughing stock of ourselves. All that is now needed to complete the opera bouffe is a headline in the newspapers, “Italians Occupy Addis Ababa, British evacuate Eastern Med”.’ 21 Dino Grandi, the Italian ambassador in London, reported that although the British realized, ‘the Italian empire in Ethiopia was also the Italian Mediterranean empire’, they feared to act. 22

The Fascists oriented their Mediterranean quite differently from that of the British: north–south rather than west–east. Apart from metropolitan Italy, the pre-Fascist Italy–stretching around the northern end of the Adriatic to Pola, a naval base, and the city of Zara in Dalmatia–had acquired colonies from the dying Ottoman Empire: the twin lands of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in North Africa, and the islands of the Dodecanese in the Aegean, chief amongst them Rhodes, Cos and Leros.

Mussolini developed this existing empire. In 1936 he sent Cesare Maria De Vecchi, one of the ‘heroes’ of the Fascist seizure of power, to govern the Dodecanese. De Vecchi built himself a huge palace on Rhodes and managed to alienate the native population through a combination of excess and incompetence. He pursued, for instance, assimilation–banning all newspapers in Greek–and segregation–banning intermarriage–at the same time. 23 The Italians fortified the islands, building airfields and naval facilities. Leros had a deep-water harbour from which destroyers, torpedo boats and submarines could operate. 24 The island became known as ‘the Malta of the Aegean’. The Turks called it the ‘gun’ pointing at Turkey. They suggested to anyone who listened that the base was the first link in the chain that would give Italy dominance in the eastern basin of the Mediterranean. 25

Ciano’s nascent Ufficio Spagna also fell greedily on the idea of a base in the western Mediterranean. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936 gave the Fascists the chance to seize such a base. For the Italians the war was as much about bases in the Balearics as it was about Madrid. 26 Months before any Italian armies went to Franco’s aid on the mainland, the Italians were already fighting a parallel war for the Balearic islands of Majorca, Minorca and Ibiza. A particularly brutal Black Shirt leader, Arconovaldo Bonaccorsi–known as the Conte Rossi because of his red hair and beard–was sent to Majorca, announcing that he was there to ensure ‘the triumph of Latin and Christian civilization, menaced by the international rabble at Moscow’s orders that want to bolshevize the peoples of the Mediterranean basin’. Rossi carried out a reign of terror, murdering about three thousand people during his occupation of the Balearics. ‘Daily radical cleansing of places and infected people is carried out,’ he boasted. 27 Soon Rossi was reinforced by a small air force. The aircraft operated to such good effect that the Republicans were forced to withdraw at the beginning of September 1936.

For years, those who observed Fascist ambitions had suspected that Mussolini coveted the Balearics: now the Fascists were firmly in charge. 28 Indeed Mussolini opened his November 1936 oration on the need for an expanded war in Spain with the cry, ‘the Balearics are in our hands’. 29 It was only in the light of the triumph in the Balearics that Mussolini fully embraced Franco. The Duce ordered that Franco should receive both an Italian air force and army. One month later the Black Shirts surreptitiously set sail from the port of Gaeta, north of Naples. Within months nearly 50,000 Italian troops were fighting in Spain. Their first mission was to seize Spain’s Mediterranean coastline. 30