Полная версия:

In the Night Wood

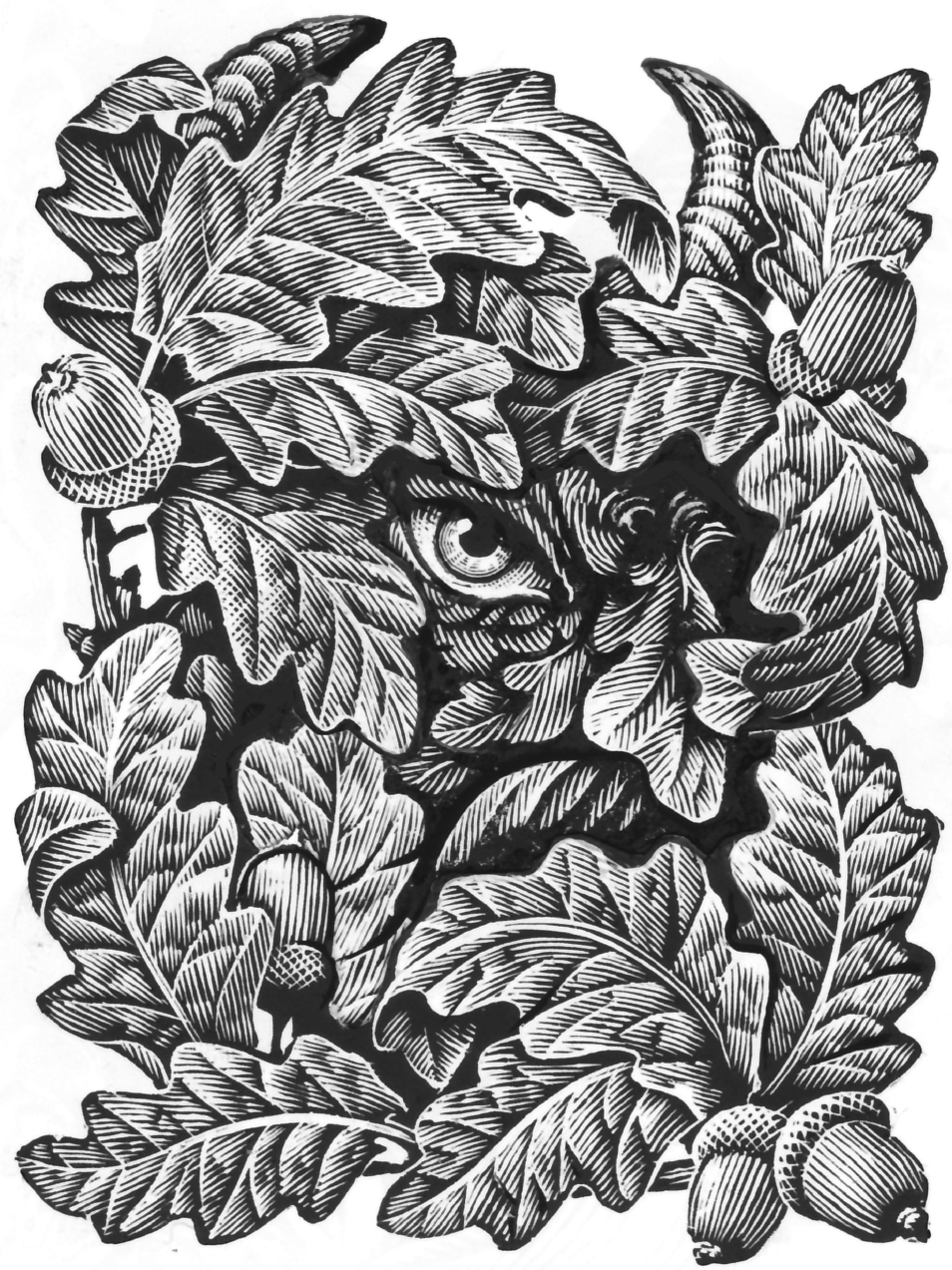

Frontispiece

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Dale Bailey 2018

Cover design by Andrew Davis © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover images © Shutterstock.com

Frontispiece illustration © Andrew Davidson

Dale Bailey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008329167

Ebook Edition © September 2018 ISBN: 9780008329174

Version: 2018-11-23

Dedication

For Pam and Sally

Epigraph

The specific mode of existence of man implies the need of his learning what happens, and above all what can happen, in the world around him and in his own interior world. That it is a matter of the structure of the human condition is shown, inter alia, by the existential necessity of listening to stories and fairy tales, even in the most tragic of circumstances.

— MIRCEA ELIADE, THE FORBIDDEN FOREST

Gretel began to cry and said,

“How are we to get out of the forest now?”

— THE BROTHERS GRIMM, “HANSEL AND GRETEL”

Contents

Cover

Frontispiece

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Once Upon a Time …

Prelude

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

I: Hollow House

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

II: Yarrow

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

III: In the Night Wood

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

About the Publisher

PRELUDE

By the time the Moon arose and let down her golden skirts, Laura was sore afraid. In the pale light she stumbled through a ring of sinister yews into a glade where stood a single bearded oak, hoary and not unkind.

“I met you once in a dream,” she said.

“And I you in my long, arboreal sleep,” replied Grandfather Oak (for that was his name).

“Isn’t that odd?” Laura said to the tree.

“Not at all,” said Grandfather Oak, nodding sagely. “The Story is rich in coincidence.”

“What kind of Story is it?” asked Laura.

And just then the North Wind swept through the trees, and Grandfather Oak shivered all his branches and dropped down a curtain of golden leaves. “It is not a happy Story,” he said. “But so few Stories are.”

— CAEDMON HOLLOW, IN THE NIGHT WOOD

1

Hollow House came to them as such events befall orphans in tales, unexpectedly, and in the hour of their greatest need: salvation in the form of a long blue envelope shoved in among the day’s haul of pizza-delivery flyers, catalogs, and credit card solicitations. That’s how Charles would pitch it to Erin, anyway, sitting across from her in the night kitchen, with the envelope and its faintly exotic Royal Mail stamp lying on the table between them. Yet it felt to Charles Hayden like the culminating moment in some obscure chain of events that had been building, link by link, through all the thirty-six years of his life — through centuries even, though he could not have imagined that at the time.

Where do tales begin, after all?

Once upon a time.

In the months that followed, those words — and the stories they conjured up for him — would echo in Charles’s mind. Little Red Cap and Briar Rose and Hansel and Gretel, abandoned among the dark trees by their henpecked father and his wicked second wife. Charles would think of them most of all, footsore and afraid when at last they chanced upon a cottage made of gingerbread and spun sugar and stopped to feast upon it, little suspecting the witch who lurked within, ravenous with hungers of her own.

Once upon a time.

So tales begin, each alike in some desperate season. Yet how many other crises — starting points for altogether different tales — wait to unfold themselves in the rich loam of every story, like seeds germinating among the roots of a full-grown tree? How came that father to be so faithless? What made his wife so cruel? What brought that witch to those woods and imparted to her appetites so unsavory?

So many links in the chain of circumstance. So many stories inside stories, waiting to be told.

Once upon a time.

Once upon a time, at the wake for a grandfather he had never known in life, a boy named Charles Hayden, his mother’s only child, scrawny and bespectacled and always a little bit afraid, sought refuge in the library of the sprawling house his mother had grown up in. “The ancestral manse,” Kit (she was that kind of mother) had called it when she told him they’d be going there, and even at age eight he could detect the bitter edge in her voice. Charles had never seen anything like it — not just the house, but the library itself, a single room two or three times the size of the whole apartment he shared with Kit, furnished in dark, glossy wood and soft leather, and lined with books on every wall. His sneakers were silent on the plush rugs, and as he looked around, slack-jawed in wonder, the boisterous cries of his cousins on the lawn wafted dimly through the sun-shot Palladian windows.

Charles had never met the cousins before. He’d never met any of these people; he hadn’t even known they existed. Puttering up the winding driveway this morning in their wheezing old Honda, he’d felt like a child in a story, waking one morning to discover that he’s a prince in hiding, that his parents (his parent) were not his parents after all, but faithful retainers to an exiled king. Prince or no, the cousins — a thuggish trio of older boys clad in stylish dress clothes that put to shame his ill-fitting cords and secondhand oxford (the frayed tail already hanging out) — had taken an instant dislike to this impostor in their midst. Nor had anyone else seemed particularly enamored of Charles’s presence. Even now he could hear adult voices contending in the elegant chambers beyond the open door, Kit’s querulous and pleading, and those of his two aunts (Regan and Goneril, Kit called them) firm and unyielding.

Adult matters. Charles turned his attention to the books. Sauntering the length of a shelf, he trailed one finger idly along beside him, bump bump bump across the spines of the books, like a kid dragging a stick down a picket fence. At last, he turned and plucked down by chance from the rows of books a single volume, bound in glistening brown leather, with red bands on the spine.

Outside the door, his mother’s voice rose sharply.

One of the aunts snapped something in response.

In the stillness that followed — even the cousins had fallen silent — Charles examined the book. The supple leather boards were embossed with some kind of complex design. He studied it, mapping the pattern — a labyrinth of ridges and whorls — with the ball of his thumb. Then he opened the book. The frontispiece echoed the motif inscribed on the cover; here, he could see it clearly, a stylized forest scene: gnarled trees with serpentine roots and branches twining about one another in sinuous profusion. Twisted, and bearded with lichen, the trees projected an oddly menacing aura of sentience — branches like clutching fingers, a hollow like a screaming mouth. Strange faces, seemingly chance intersections of leaf and bough, peered out at him from the foliage: a grinning serpent, a malevolent cat, an owl with the face of a frightened child.

And on the facing page:

In the Night Wood

by

Caedmon Hollow

Looking down at the words — like the frontispiece, garlanded with foliage — Charles felt his heart quicken. The age-darkened pages smelled like a cellar of exotic spices thrown open in an airless room, and their texture, faintly ridged underneath his fingers and laid through with pale equidistant lines, felt like the latitudes of a world yet unmapped. Those sly foxlike faces, peering everywhere out at him from tangles of leaf and briar, seemed to consult among themselves, a confabulation of whispers too faint to quite discern, there and gone again in the same breath. His finger crept out to turn the page.

“Charles.”

He looked up, startled.

Kit stood in the doorway, her thin mouth compressed into a bloodless line. Staring at her, Charles saw for the first time — as with an adult’s eyes — how old she looked, how tired, how different from her immaculate sisters, lacquered to within an inch of their lives. He thought of his grandfather, that stranger in the casket who shared Kit’s jutting cheekbones and deep blue eyes. It fell upon him like a blow, that image. It nearly staggered him.

“We’re leaving, Charles. Get your things.”

He swallowed. “Okay.”

She held his gaze a moment longer. Then she was gone.

Charles started to slide the book back into its slot on the shelf — but hesitated. He felt once again that sense of tremulous significance, as if the flow of events had been shunted into a new and unsuspected channel. As if thrones and dominions more powerful than he could imagine had stepped briefly from behind some hidden curtain in the air. The room almost hummed with their presence.

He could not surrender the book, this artifact of a life that, but for Kit, could have been his own: the manicured lawns and the vast rooms and the great library most of all. (Libraries would be the lodestone of his life.) He would have to tuck it into his knapsack and spirit it out of the house.

He would have to steal it.

As this conviction took root inside him, Charles felt a surge of panic. Terror and exhilaration vibrated through him like a plucked chord.

He wanted to flee, to cast aside the book and, for the first time all day, seek human companionship. Even the unbearable cousins would do. But he could not seem to pry loose his frozen fingers. As of its own accord, the book fell open in his hands, and he found himself flipping past the frontispiece and the title page to the text itself: Chapter One.

The initial letter of the opening sentence was inset and oversized and bound in ornate runners of leaf and vine. For a moment, his inexperienced eye could not decode it. And then abruptly, the entire phrase snapped into focus.

Once upon a time, it said.

2

But for the book, Charles might have forgotten the entire episode. For all Kit ever spoke of it, the whole day might have been an elaborate fantasy inspired by their itinerant existence in a succession of cheap walk-up apartments, sustained by a series of minimum-wage jobs (“Fired again,” she always told him ruefully when one of them headed south) and well-meaning but feckless boyfriends, most of whom exuded a sweet-smelling haze that Charles would many years later come to recognize as the scent of pot.

But the stolen leather volume had a way of turning up anew with each fresh move — in a box of mateless socks or shoved in among the well-thumbed paperbacks on Kit’s bedroom shelf. Finally, home sick one afternoon in Baltimore — they’d only just moved; he must have been nine or ten at the time — Charles actually read it.

The story showed up in his dreams for days thereafter, a hallucinatory montage of great trees pressing close upon a woodland path, a terrified child, a horned king, his pale horse steaming at the nostrils in the midnight air. Afterward, Charles could never be quite certain whether to attribute the eidetic quality of these images to the book itself or to the feverish condition he’d been in when he read it. He meant to go back and have another look, but the pressures attendant upon being the new kid at school (he was always the new kid at school, and a bookish, nerdy kid at that) intervened.

By the time he did try to go back, two or three moves later, the book had evaporated, vanished in one of the more recent relocations. And this time it really was forgotten.

It might have stayed that way had Charles not enrolled in a seminar in Victorian nonsense literature fifteen years later. He’d been on his own for years by then (sometimes it felt like he’d always been on his own, like he’d spent more time parenting Kit than vice versa), a scholarship kid who did well enough as an undergraduate English major to snag a teaching assistantship at one of the big state Ph.D. mills. There, he divided his time between a derelict apartment in the student ghetto, cramped classrooms, where he held forth on the merits of the thesis statement to bored freshmen only four or five years his junior, and the classes he was taking, where the air was thick with intellectual posturing and professional anxiety. He’d enrolled in the nonsense seminar out of necessity, when the class he’d really wanted — a course in literary theory taught by a fading Ivy League enfant terrible who planed in once a week to teach his classes and then promptly vanished — filled up before he could get in.

So it happened that Charles — at twenty-five, still scrawny and bespectacled, still a little bit afraid — found himself in the university library one cold February evening, reading up on Edward Lear. He’d just started nodding when his eye chanced upon a footnote referencing an obscure Victorian fantasist by the name of Caedmon Hollow. Now almost entirely forgotten (Charles read), Hollow had written only a single book: In the Night Wood.

The title jerked Charles fully awake. The library was silent, cool, and all but abandoned at this late hour. A hard snow ticked against the windows, but despite the chill, a thick column of heat climbed through him. Rereading the footnote, he felt time slip. He was a child again, alone in his grandfather’s enormous library with the cries of the dreadful triumvirate of cousins sounding far away beyond the great arched windows. Long-forgotten details from that single feverish reading flooded through him: a full moon looking down through the mists of the Night Wood; the Mere of Souls, black in its midnight glade; a child flying through the whispering trees; the Horned King upon his pale horse.

“Shit,” he whispered, setting aside the book. He stood and made his way across the reading room to a bank of terminals and tapped the title into the catalog. A few minutes later, clutching a call slip in one hand, Charles caught an elevator to an upper floor. Walking the labyrinth of stacks and dragging a single finger in his wake, bump bump bump across the spines of the books, Charles nearly missed it.

He supposed he’d been expecting the same beautiful, leather-bound volume he’d plucked from his grandfather’s shelf. The library’s copy was infinitely more practical, a thin, sturdy book bound in blue boards — or rebound, he surmised when he flipped it open to find the same baroque frontispiece. It was a woodcut, he saw, the lines strong and sure.

Wily faces peered out at him from behind the boles of the ancient, lichen-shrouded trees, their great splayed roots knuckling down into beds of rich, damp soil. As he gazed at them, the faces seemed to shift and draw back into the foliage, only to appear again, peeping out at him from some neighboring bower of wood and leaf. He imagined that he overheard their whispered conversations in the air around him.

He started back toward the elevator, flipping to the first chapter, that opening invocation —

Once upon a time

— ringing in his head. When he turned the corner and collided with someone strolling the other way, Charles had a brief and not unpleasant impression that he’d been enveloped in a feminine cloud, faintly redolent of lavender. Caught off balance, he threw out his arms to catch himself —

“Watch where you’re going!” the girl cried.

— and went over backward. He thumped to the floor, his glasses flying one way, his book the other. He was still scrambling for the former when the cloud of perfume enveloped him once again.

“Steady there,” the girl said. “You okay?”

He blinked at her owlishly. “Yeah, I —” His fingers closed over his glasses. He fumbled with them, and she swam briefly into focus, a small, lean brunette in her mid-twenties, with a prominently boned face and wide-set hazel eyes, bright with amusement — not beautiful, exactly, but … striking, Kit would have called her. Out of his league, anyway, that much was sure. “I guess I wasn’t looking where I was going.”

“I guess not.”

She took his hand and heaved him to his feet, startling him all over again. “Steady,” she said as he snatched at the nearest shelf. He was still trying to get his glasses adjusted — he thought he might have bent the frames — when she reappeared with his book.

“What was it you were so intent on, anyway?”

“Nothing,” he sputtered. “It was — I —”

Waving him into silence, she flipped the book over to see for herself. She laughed out loud. “Small world.”

“What,” Charles said, still fussing with his glasses. “You’ve read it?”

“Once upon a time, long ago.”

“Not many people have read it.”

“Not like I have,” she said.

“What do you mean?”

“You wouldn’t believe me if I told you,” she said, shoving the book at him. “Here. Hold still.” Shaking her head, she reached out and straightened his glasses. Maybe they weren’t bent after all. “Better?”

“Yeah, I guess so. Thanks.”

“You bet.” Reaching out once again — Charles forced himself not to step back — the girl brushed a speck of imaginary dust from his shoulder. “All set?”

“Yeah, I mean — Yeah.”

“Good.”

Smiling, the girl slipped past him into the stacks.

“Wait,” Charles said. “I wanted —”

But she was already gone, leaving a perfect girl-shaped vacuum in the air before him. “Shit,” Charles said, turning to look after her, but the library was cold and empty, a forest of nine-foot shelves branching off as far as the eye could see.

Then, in one of the few courageous acts in his life up to then, he gave chase. He turned the corner of one row of stacks and accelerated. “Hey,” he called. “Wait up.” And when he reached the next intersection — almost at a run — he nearly collided with her again. She was waiting there, leaning against a shelf, arms crossed, a sly smile upon her-face.

“You’re aching for a concussion today, aren’t you?” she said. “You sounded like a herd of wildebeests. I thought you were going to brain yourself.”

“I wanted to ask you something,” he said. “I wanted to know what you meant by ‘small world.’”

“That’s a complicated answer.”

“Let me buy you a cup of coffee.” Once the phrase passed his lips, the room seemed suddenly airless. He was not the kind of man to ask strange women out for coffee. He was, in fact, not the kind of man to ask out women at all — not for lack of interest, but for lack of confidence. Assuming rejection, he found it easier to save everyone the trouble. So when she said —

“Sure. Coffee sounds good.”

— he exhaled an audible sigh of relief.

3

Her name was Erin, her secret unexpected (to say the least).

Coincidence, Charles called it. Coincidence that he had plucked down that book in his grandfather’s library (she dismissed it all as chance). Coincidence that he had gone on to seek a Ph.D. in English. Coincidence that on a late night in the library with snow slanting out of the black February sky, he should run (literally) into the great-great-exponentially-great-something-or-other of Caedmon Hollow himself, who might have influenced, in subtle ways, Charles’s pathway to this place.

Fate, he thought. The Worm Ouroboros. The snake biting its own tail. He had come full circle. And for a moment Charles glimpsed a vast, secret world, intersecting lines of power running just beyond the limits of human perception — a great story in which they were all of them embedded, moving toward some unimaginable conclusion.