Полная версия:

The Real Band of Brothers: First-hand accounts from the last British survivors of the Spanish Civil War

THE REAL BAND

OF BROTHERS

First-hand accounts from the last British survivors of the Spanish Civil War

MAX ARTHUR

This book is dedicated to the 2,500 British and Irish

volunteers who fought alongside the Spanish people in

their heroic struggle against Fascism from 1936 to 1939.

And, in particular, to the 526 who lost their lives.

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

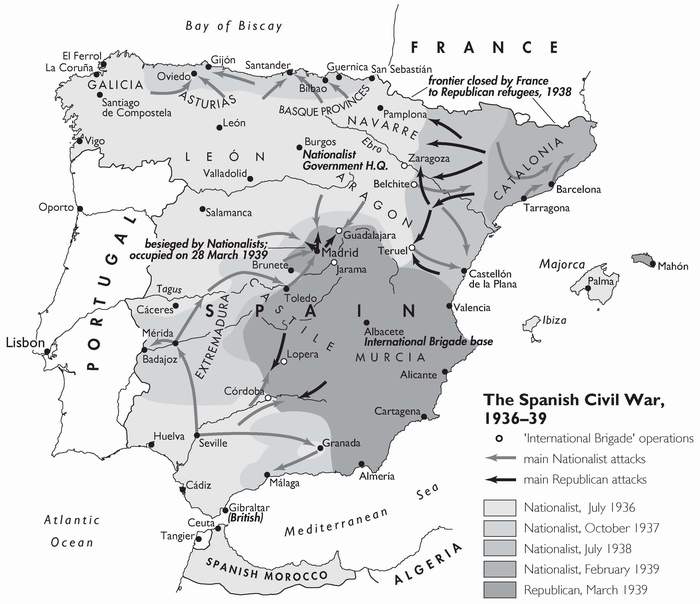

Map

PREFACE

LOU KENTON

PENNY FEIWEL

JACK JONES

JACK EDWARDS

BOB DOYLE

SAM LESSER

LES GIBSON

PADDY COCHRANE

TIMELINE OF THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR

LA PASIONARIAS SPEECH

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Praise

Copyright

About the Publisher

PREFACE

The Real Band of Brothers stems from a chance meeting with the actor Alison Steadman in 2003 at the launch of my book Forgotten Voices of the Great War, where she read the moving words of Kitty Eckersley, whose husband had died on the Western Front. I met Alison again five years later and she introduced me to her friend, Marlene Sidaway, also an actor. Marlene lived for many years with David Marshall, one of the earliest British volunteers in the International Brigades, and was also the Secretary of the International Brigade Memorial Trust. In this role, she told me, she was in close touch with the last British survivors of the Brigade—and, from that meeting, the book began to take shape.

To many people in the UK today, the Spanish Civil War remains something of a grey area—a conflict in which British troops were not engaged, and one that was eclipsed in the public perception by the Second World War. But the Spanish Civil War was a vicious and prolonged battle, the repercussions of which still reverberate through that country today. Many towns were destroyed and their populations massacred; the lives of half a million men, women and children were lost. Furthermore, while the British Government did not support the democratically elected Republican regime in Spain, individuals from the UK and other nations across Europe, incensed by the injustice of the Spanish struggle, volunteered their services to fight for democracy.

In July 1936, the army generals including General Franco led a savage military coup to depose Spain’s elected government—a left-wing coalition of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), the Republican left, the Communists and various regional nationalist groups. This Fascist aggression was not isolated in Spain; in the early 1930s, extreme right-wing movements were also growing under Mussolini in Italy, Hitler in Germany and, to the alarm of left-wing parties there, under Oswald Mosley in Britain.

Supported by his Blackshirts, Mosley tried to impose his authoritarian philosophies on the working-class population of London’s East End, and his political meetings often ended in violence. Eventually, in a well-orchestrated show of strength, groups of trade unionists, Communists and Jews joined forces to denounce Mosley’s racist ideology and prevent his jackbooted thugs from marching through their streets—it was a stand-off that became known as the infamous Battle of Cable Street.

Some of the men and women who had seen off Mosley on that fateful day later volunteered to fight in Spain in what became known as the International Brigades. Much to the fury of these volunteers, the British Government of the day had adopted a policy of non-intervention. Not only would there be no British military support for the Spanish against Franco’s forces, there would be no official medical or material aid either. Although news from the Spanish war was sparse in any but the left-wing press, a growing number of people travelled to London to sign up with the Communist Party, and, in defiance of French laws against partisan military groups, made their way across the Channel, through France and over the Pyrenees to support the Spanish Republican army. Some were motivated by their political beliefs; others by their horror at the humanitarian catastrophe unfolding in Spain. The working people, already poor and living from hand to mouth, were facing starvation and disease, and many British doctors and nurses set out for Spain to offer their skills in order to alleviate the suffering their consciences could not ignore.

In the three-year conflict—which has been dubbed the first battle of the Second World War—many of those volunteers lost their lives. To all who freely offered their services, for whom the cause was indeed just and one they were prepared to die for, the war was a life-changing experience—and one that none would regret, despite the consequences.

As I started working on The Real Band of Brothers, just eight veterans of the International Brigades remained in Britain and, together with the award-winning documentary maker Matt Richards, I travelled across the country to interview and film these remarkable characters. The oldest, Lou Kenton, turned 100 in September 2008, and former nurse Penny Feiwel’s hundredth birthday is in April 2009. She is still full of vigour—and still cursing Franco for inflicting the terrible injuries on innocent children that she witnessed. Archaeology student Sam Lesser fought for two years to hold the City University of Madrid. Paddy Cochrane, who at seven had seen his father shot by the Black and Tans in Dublin, believed that he himself would suffer a violent death in Spain. Bob Doyle, who, after being held prisoner by the Fascists, returned years later to stamp and swear on Franco’s grave. Jack Jones would later become leader of the Transport and General Workers’ Union, and fought fearlessly at the Ebro in the last battle of the war. Les Gibson, a founder of the Young Communist League in west London, fought through Jarama, Brunete and the Ebro, and survived life-threatening colitis to return to the action. Jack Edwards, at home a very active union member and political activist, returned from the war with his determination to fight Fascism undiminished; within months he joined the RAF to continue the battle against Hitler.

Over a number of weeks I had the great pleasure of interviewing these eight extraordinary survivors in their own homes. Matt Richards recorded their testimonies on film and tape, and has subsequently written a script based on the interviews, which was commissioned as a two-part documentary for the History Channel—The Brits Who Fought for Spain.

All these old ‘Brigaders’ had endured an extremely tough Edwardian childhood, but retained an extraordinary vitality and a clear perspective on how the war had changed their lives forever. I am in awe of their still-vibrant sense of anger and defiance. Now, as I write this preface, I have just learned with great sadness of the passing of Bob Doyle—he was an indomitable spirit to the last and I was privileged to have visited him again just days before his death.

Some had told their story before, but others were opening up after a lifetime in which they had avoided talking about the war. Their testimonies are in their own words but allowance must be made for the age and frailty of their memories. Wherever possible I have checked the historical details, but sometimes the facts are buried in time. Bob Doyle and Jack Jones kindly gave me permission to use additional extracts from their respective books, Brigadista and Union Man.

It is now 70 years since the end of the Spanish Civil War, in which over 500 of the 2,500 British volunteers for the International Brigades were killed. All the survivors, however, were united in the one belief—that they were fighting against the evil of Fascism, and that it was no less than their duty to do their bit. As more than one speculated, if other European governments had supported the Spanish Republic and quashed the Fascist threat in its infancy, the course of history might have been different, and perhaps there would even have been no Second World War.

Whatever their sense of the role of the Spanish Civil War in a historical context, all are personally bound by the values of comradeship and deep loyalty. They fought for a cause, asked for no payment, and saw many friends die. But every one agreed that they would do it all again.

These are their words—I have been but a catalyst.

Max Arthur

London

January 2009

LOU KENTON

Born 1 September 1908 in Stepney, east London

I was born in a block of flats—a tenement—in the East End, in Stepney, in Adler Street, which doesn’t exist any more. I had eight brothers altogether, but some died. I was the first one to be born in England (my family was originally from Ukraine). My father died of TB when I was fourteen—he was working in a sweatshop for a tailor. I missed my bar mitzvah because he’d just died.

I joined the Communist Party in 1929, because it was the only party that was fighting Fascism. I met my first wife, who came from Austria, and together we were both in the Communist Party, although she wasn’t very active—she was a masseuse and spent her lifetime working.

We all had a political dislike for the Fascists. Mosley was the leader of the Fascists in Britain and he was anti-Labour—and anti-Communist, of course—and we often had fights when they tried to break up our meetings—and we did the same to them. We hated Mosley and there were always battles going on in the East End. The headquarters of the Fascists were in Bethnal Green, and we, the Communist Party, were mostly in Stepney.

At that time London was a much-divided place—in the east there were lots of trade unions, factories and the tailoring was mostly Communist. The first big encounter was when Mosley announced that he was going to march through the East End of London on 4 October 1936. His main slogan was ‘down with the Jews’. We had enough notice to run a campaign against the march. Until then Mosley had had setbacks, but was going from strength to strength. The point we tried to bring to public attention was that this was not just a provocation of the Jews: this march was an attack on the people of Britain as a whole. We tried to win the support of all sections of the population, which indeed we did. Not only the local trade council, but trade union branches from all over London and other parts of the country, supported the campaign to stop Mosley marching through east London. Of course, the Jewish population was on our side, although the official view of the Jewish Board of Deputies was ‘Don’t make trouble—just be quiet’. But we were able to get the majority of the Jewish population of east London on our side, as well as the dockers—they were the main big sections. Every grouping also had a job to do in the organisation of the whole of what has now become known as the Battle of Cable Street. My job was to organise my own Party branch of Holborn, which included the print workers, to occupy the ground around Aldgate Station. Mosley was going to march from the Minories (around Tower Hill), where he had assembled with the help of the police, through Aldgate, along Whitechapel Road, into Bethnal Green, where he had a certain amount of support. I had two jobs, firstly for my branch to be the first line of defence in Aldgate. What we were supposed to do I don’t know—there were only about thirty or forty of us and we didn’t know how big the crowd would be. We imagined that we would hold the Mosley crowd for even a few minutes, while the rest of the crowd would rally. In the event, the crowd was great: it stretched right along the Whitechapel Road, Commercial Road, Gardiner’s Corner, right up towards Aldgate Station itself. The crowd was so thick that you couldn’t move. There were a number of trams in the area and they were stuck in the middle of the crowd. You can imagine the sight—something like half a million people with these trams stuck all over the place. Of course, the word got to Mosley, and to the police, that they couldn’t possibly go through Aldgate.

They tried to redirect the march the other way, down Leman Street from the Minories into Cable Street, making a detour of Whitechapel Road. I had a motorbike at the time and was able to whizz around the periphery of the crowd, going from section to section to warn them what was going on. We had a number of people watching the Fascists and quickly telling the crowd what was happening. We were able to get word to the majority of the crowd in Commercial Road, which was some way from Cable Street, of what was happening. The dockers themselves were manning Cable Street and had thrown up barricades. As soon as the word got around that Mosley was on the way towards Cable Street, within minutes thousands of people were there. Although hundreds of police and the Mosley crowd tried to break through, they were stopped. Mosley then had to go back to the Minories and finally the police chief said there was no possibility of them going through the East End. They turned round and went the other way, towards the City, to the Embankment, and dispersed. That was really the great Battle of Cable Street: a major historic event and the first real defeat of Mosley.

Can you imagine the celebration throughout the East End that day? People were dancing in the streets, hugging each other. They had defeated Mosley—defeated Fascism. And although people had not yet fully realised what Fascism was, they could see what the Fascists’ intentions were.

I was married to Lilian at the time and we were living in Holborn and we were both very active. I was in Holborn at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War and the branch, being more or less in the centre of London, helped to steward the big meetings taking place in Conway Hall, Farringdon Hall and Kingsway Hall. Appeals were made for money, food and support—they were very enthusiastic meetings.

I remember clearly, when the revolt started, how immediately the whole of the left-wing movement rallied in support of Spain. The majority of the people, however, didn’t take much interest and a good many were influenced by the press of the time, which condemned it as a Bolshevik, anti-Christian revolution. On our side we got to know early on about the real issues in Spain. The formation of the International Brigades gave it a personal interest, as people we knew began to make their way there. Very quickly we began to know the background to the Spanish struggle and the campaign in support of the Spanish Government grew in strength. Soon after the start of the civil war, Mussolini and Hitler sent Italian and German armies and air force over to help Franco. The Spanish Government, the legitimate government of the day, tried to buy arms. Britain and France were able to win the support of the League of Nations on a policy of so-called ‘non-intervention’. The reality of non-intervention meant that the Spanish Government was unable to buy arms, while the Fascists were free to buy what they wanted. The Spaniards were only able to get arms from Russia in a limited quantity, and from Mexico. Right through the war the army of the Spanish Government was far worse equipped than the Fascist side.

In Britain the movement grew in a number of ways. An organisation called British Medical Aid had been set up to raise money for ambulances. Very soon they opened first one and then another hospital in Spain. British doctors and nurses went to service these and other front-line hospitals. There was a great campaign to raise money and whole lorryloads of food were sent. There were also the youth food ships for Spain, which brought regular supplies. The British navy blockaded the coast and tried to stop the food ships, but several got through the blockade. Then, very soon, the refugees from the Basque country came over—we had several hundred Basque children in Britain who were looked after mostly in and around London. I think hardly a week went by without demonstrations and meetings taking place. Gradually the movement grew and became a very powerful crusade.

While this was happening individuals were going to Spain, isolated from each other, and joining one of the Republican units when they got there. Then the call went out throughout the whole world for volunteers to form the International Brigades.

One evening myself and Lilian and my dear friend Ben Glazer walked along the Embankment. We walked—stopped at many coffee stalls—talking, wondering what it would be like in Spain. We didn’t finally decide until we reached a coffee stall at Westminster Bridge, opposite the House of Commons. I think we had already decided to go, but didn’t say so in as many words. I think we were deeply fearful in our hearts, but none of us wanted to show our fears. What would it be like? Would we ever come back? What if we were captured? And when we decided—how we embraced! Lilian kissed us both. We linked arms and walked almost cheerfully down Whitehall to the all-night Lyons Corner House just off Trafalgar Square for more coffee and eggs and bacon. From there we decided that tomorrow morning we would go and volunteer.

Lilian and Ben both went off the next day. It was the last time I was to see Ben.

I was accepted, but the Party asked me to hold fire for three or four weeks while I cleared up the work that I was involved in as secretary. When I got to work next day I handed in my notice, and the Father of Chapel in charge of the print said, ‘What do you think you’re doing? You can’t just walk out, jobs are very precious.’ But I said, ‘I’m going to Spain.’ In those days an apprenticeship was so important—if you got a job you’d got it for life.

While Lilian went with the British Medical Aid Committee, Ben and the others had to make their own way to Paris, then through the Pyrenees. If you went through the British Medical Aid you could get your passport and the visa for Spain—but you also had to sign a document at the Foreign Office saying that if you were in trouble you wouldn’t call on the British Ambassador. That was fine. Lilian and I sold our home and gave our stuff away. I went to live in a room with Phil Piratin in east London, pending the time when I was ready to go. When I went along, blow me, they had changed the arrangements and they no longer, at least at that particular time, accepted anybody without military experience.

What to do? I went to the British Medical Aid and they said, ‘Yes, we will have you, if you can drive a lorry and service it.’ Again, what to do? So I went along to a garage in Walworth Road, offered my services free if I could be taught how to change wheels, change tyres, drive a lorry, etc. I went every evening after work and worked there for seven or eight hours. After about three or four weeks I felt competent enough to drive a lorry, went back to the Medical Aid and said I was ready to go on my motorbike but could also drive an ambulance or a lorry. I went off three or four days later.

My mother knew that Lilian had gone and kept asking, ‘Are you going?’ and ‘Must you go?’ and all the things a mother would say. I was anxious not to upset her, and, in the clumsy way most young people deal with these matters, I said that, if she was going to cry every time I came round before leaving, I wouldn’t come again—just go off. An awful thing to say!

I asked a friend to be present when I said goodbye. There was I, all packed, equipped with a new pair of leather leggings, leather gloves, leather jacket—which I had never had before. I kissed my mother goodbye, turned around the top of the road and waved. Later I was told she didn’t cry until I had gone, and then she broke down.

Came the day when I was going, word got round. I belonged to a club, the YCL (Young Communist League), and some dockers all came to the top of the street, Adler Street, between Whitechapel and Commercial Road, to see me off. There must have been several hundred, because I was still one of the first. I got on my bike, waved to them and started off. You won’t believe this: I didn’t have a map. I had no idea which way to go. All I knew was to get to the Elephant and Castle and head for Dover. I had my passport, visa and signed documents from the Foreign Office and knew I had to make my way to Barcelona. I can’t remember how I ever got there. I vaguely remember going right across France, making my way to the south.

I used to sleep by the roadside every night—I didn’t have money for lodgings. I had to get to Perpignan [to enter Spain] and how on earth I got there I don’t know. I had just a little money the crowd in London had collected for me so I could eat on the road. When I got to Perpignan I thought, ‘at last, Spain’. I looked and I couldn’t see any signs but I saw a crowd of workers having a cup of tea in a café. I went up to them and asked which was the way to Spain. They couldn’t speak English and I couldn’t speak Spanish, so I said, ‘Me, Spain, “Boom Boom!”.’ So when they stopped laughing they gathered round me, gave me a meal, and showed me the road to España, the first time I’d ever seen the sign for España.

My first real recollection of Spain was arriving at a great castle at Figueres—an enormous place—and outside the gates were two men on sentry duty. I stopped and asked them where to go. They spoke a little English and opened the gate. I rode in through this gate and the square of the castle was like a fort—as big as Trafalgar Square—hundreds if not thousands of men sitting around talking. I later learnt that was the first staging post for the people who had climbed the Pyrenees. I was the first one who had arrived on a motorbike. I think it was an American who first said to me, ‘If you want to keep that bike, never leave it, even to go to the bog—because there are so many people who would like to have your bike.’

There were literally hundreds who had found their way to the castle at Figueres. They’d walked over the mountains and they had their feet seen to and were given food. Each group from the different countries gathered together. There was a group from Britain and I went and joined them, and they were very keen to see a bloke with a motorbike. Several asked me if they could travel with me on the bike, but I said no—I was going to pick my wife up.

I went to Barcelona where the offices of the Brigade were. Remembering what the American had said, I saw a policeman and tried to explain to him—though of course he didn’t speak a word of English. I somehow managed to persuade him to look after my bike while I was in the office and he nodded. He straddled the bike and with his hand on his revolver he was going to shoot anybody who’d try and pinch it. I got my instructions to go to a little town called Benicasim. I slept in the office that night. The next morning I went by bike from Barcelona to the HQ in Valencia, where there was a convalescent home for the British Battalion. I didn’t know at the time, but, looking back later, I realise that I had arrived in Spain at the end of the Battle of Jarama in February 1937, which was the great turning point of the war. Until then the Fascists were advancing very rapidly; they were right in front of Madrid. If Madrid had fallen in those days, less than a year after the start of the war, it would have been the end. And the call went out, ‘Everything for Madrid—save Madrid’. The British Battalion had been building up and training as a unit. They hadn’t yet quite had their full training, but, because of the urgency of the situation, were thrown into the front line.