Полная версия:

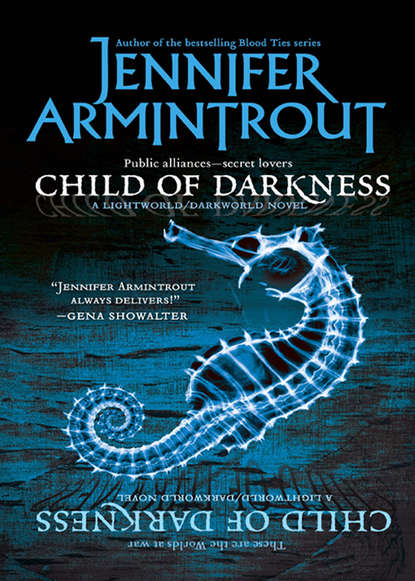

Child Of Darkness

Praise for the novels of Jennifer Armintrout

“Every character is drawn in vivid detail, driving the action from point to point in a way that never lets up.”

—The Eternal Night on The Turning

“[Armintrout’s] use of description varies between chilling, beautiful, and disturbing…[a] unique take on vampires.”

—The Romance Readers Connection

“Armintrout continues her Blood Ties series with style and verve, taking the reader to a completely convincing but alien world where anything can—and does—happen.”

—Romantic Times BOOKreviews on Possession

“The relationships between the characters are complicated and layered in ways that many authors don’t bother with.”

—Vampire Genre on Possession

“[This book] will stun readers. Not to be missed.”

—The Romance Readers Connection

on Ashes to Ashes

“Entertaining and often steamy romances run parallel to the supernatural action without dominating the pages.”

—Darque Reviews on All Soul’s Night

“Armintrout pulls out all the stops…a bloody good read.”

—Romantic Times BOOKreviews

on All Souls’ Night

Books by Jennifer Armintrout

Blood Ties

BOOK ONE: THE TURNING

BOOK TWO: POSSESSION

BOOK THREE: ASHES TO ASHES

BOOK FOUR: ALL SOULS’ NIGHT

The Lightworld/Darkworld novels

QUEENE OF LIGHT

CHILD OF DARKNESS

and

VEIL OF SHADOWS

Available December 2009

JENNIFER ARMINTROUT

CHILD OF DARKNESS

A LIGHTWORLD/DARKWORLD NOVEL

This book is dedicated to Tez Miller.

Not just because she won the Twitter contest

and this was the prize, but also because she is

one of the nicest romance bloggers I have met.

Contents

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Acknowledgments

Prologue

On the night she was born, the Palace rejoiced.

But her mother did not.

Lying in her bed, the infant tucked closely to her side, Ayla despaired. Protect her, the Goddess had said. It had been so easy when the child had been a part of her. Now, she was a part of the world, a world that was more cruel and difficult than one of her race should have to face. Protecting her would not be as simple now.

The child was perfect, though more Human in appearance than even her mother. Faery babes were born pale, tinged with green, and spindly like the roots of a plant. This child was plump and pink, with a shock of flame-orange hair sprouting in tufts from her head. Two feathered, black wings were tucked against her small back, and they stirred as she slept, as though she dreamed of a day when she could use them.

The door to the Queene’s chambers opened to admit the child’s father. Malachi, once divine, now mortal. He approached carefully, as though afraid to see what lay beside Ayla in the bed.

“She is…whole?” He had voiced his fears to Ayla only once, late at night, when he’d recounted for her the sights of the pitiful children he’d had to escort to Aether, the domain of the Angels on Earth. He had been afraid that the child would be malformed, as a punishment for his fall.

It relieved Ayla that she was able to show him how foolish that fear had been. “She is whole.” She hesitated. “But her wings…they are the same as yours. Everyone will know she is not Garret’s child.”

Emboldened by the news that his child was not deformed as a consequence of his actions, he came forward to see her. “I am glad they will know. I would not care if that traitor’s name was never uttered in the Palace again.”

Ayla stroked the downy skin between her daughter’s wings. “No. No one must ever know. To keep her safe.”

“It would be safer for her to be thought of as a bastard,” he argued, and Ayla could not be surprised. She’d thought of it, herself.

“It would be. She would never be Queene, and so, she would never be a target for an Assassin’s blade. As heir to my throne, she will be,” Ayla mused aloud, as if thinking of it for the first time. “But if she were revealed to be a bastard, her inheritance of my throne might be compromised.”

“Your throne,” Malachi repeated. The words sounded like poison he needed to spit from his mouth.

Ayla did not bristle, as she used to. Over the months since her coronation, it had become clearer and clearer to her that while Malachi loved her and would stay at her side in the Lightworld, he hated the Faery Court. She’d feared, for a time, that it was her he hated, that he stayed in the Lightworld simply because he had nowhere else to go. But she had resolved to tolerate it, because she’d caused him to lose his immortality, and the kind Human who’d saved his life had died because of her.

It had only been when Cedric, her closest advisor, had politely suggested the real reason for Malachi’s hatred of her position—that it kept her from him, in all but the physical sense—that it had become clear. And now, she felt foolish at the mere memory of those fears.

“I do not worry for myself. Or, perhaps I do. If the child is known to not be Garret’s, those who wished to remove me from the Court could use it against me. If I were officially declared a traitor, think of what might happen to her.” Speaking of death aloud, in this room where Queene Mabb had fallen under Garret’s hand, sent a ripple of apprehension through her, as if her own death brushed over her on its way to the future. “No, it would be safer for her to be thought of as the heir to the throne, and endangered in that way, than to be cast on the mercy of the Court and be subject to their machinations.”

She pulled the blanket over the child—her daughter, how strange to think those words!—so that her form was obscured. “Bring Cedric. I need his counsel.”

Malachi’s fists clenched at his sides. She knew his feelings for her advisor. Malachi wished to be the closest to her, in every way. And he was, in most ways, though he would not believe it no matter how many times she reassured him. But Cedric knew the Lightworld as no one else did, not even Flidais or the other members of the council, and Ayla called on him when a problem seemed too large or complicated to solve on her own. It was impossible to convince Malachi that she did not view his inexperience with Lightworld politics as a lack of ability.

He did not argue and, with a last, longing look at his child, turned and left. He returned with Cedric quickly; no doubt both men had waited in the antechamber beyond for the child’s arrival.

When the door was shut, Ayla pulled back the covers to reveal the tiny babe at her side. She studied Cedric’s expression carefully, but he gave nothing away.

“She is perfect, Your Majesty. You both should be very proud that your union resulted in such a beautiful child.” His tone was schooled through years of politics; he never missed a step by disclosing something too soon. “Have you a name for her?”

“Cerridwen,” Ayla answered, though she had not thought of it until now. “After that face of the Goddess.”

“It is a strong name,” Cedric said with a Courtly bow. “The Royal Heir, Cerridwen.”

“It is a mockery of the true God,” Malachi put in, but without malice. He often made such pronouncements, without feeling, betraying that he had once been a creature without emotion or will, completely subservient to the One God of the Humans.

Ayla ignored him, choosing instead to press on with her advisor. “And what of her appearance. Do you not see anything odd, Cedric?”

As if freed of some invisible bond, Cedric spoke in earnest now. “She appears to be Human. That is explained away easily enough, as you are half Human yourself. Plus, most Fae have little experience with young of their own species to tell the difference readily, especially from a distance. But her wings, Your Majesty. There are already rumors that you will make Malachi your Royal Consort. If she is seen to have such a similar feature as him, especially one that is so unlike anything born to the Fae…No doubt you’ve thought of this already.”

“She has,” Malachi said, coming to sit on the bed beside Ayla, as if he could no longer stand the separation. “And we have decided that it is in the best interest of the child that no one discover her true parentage.” He leveled his gaze at Ayla, and the sudden sorrow in his eyes jolted her. “Not even the child should know, lest she let the information loose by mistake.”

“That is wise, Malachi,” Cedric acknowledged with a nod of his head. “However, it is not practical to keep the girl locked away forever. The Court will question her absence at royal functions. Her existence might even be called into question. Even if hiding her was possible, she will have to be attended by servants, and servants do talk.”

Ayla waved a hand to stop him. She was tired, and wished to be alone with her child on this first night of its life, without the nagging fear that so much was left to do. “I agree with you. We cannot hide her away. As for the servants, I will leave that to your discretion. You know which servants in the Palace can be trusted, not only to keep her secret, but to care for her as she deserves.” She tapped one finger on her lips, as if considering, though her mind was already made up on the next matter. “I believe I shall enact a new law. All Faeries at Court shall bind and cover their wings. In homage to Mabb, of course, who always hid her own. The anniversary of her death is only a few weeks away. Surely we can keep Cerridwen hidden until then?”

Cedric did not respond immediately, and he looked as though he worked over the problem of what to say to her in his mind. “I do not believe Your Majesty has thought of all the implications such a declaration will entail. There will be those who resist.”

“And they shall be turned away from Court until they comply with my wishes. This is not unheard of. Mabb often used such tactics,” Ayla answered quickly.

“With respect to Mabb—” and Cedric did not need to assure her of his genuineness in this respect “—do you truly wish to be seen as her equal in the eyes of your subjects?”

“My subjects clamor to be Human, though they don’t admit it.” She thought of the words of the Goddess, who’d delivered her from death, who’d revealed Ayla’s purpose to her in the barren in-between of the healing Astral plane. Nearly struck down by Garret’s ax, she had been spared to rescue the Fae from their obsession with Humanity, an obsession that the Goddess had blamed for destroying the Veil. An obsession that the exiled Fae races did not even see. Was such a proclamation, to dress in such a way as to appear more Human, a violation of the charge given to her by the Goddess?

No, it was for the greater good of her race. It was buying time for her tiny daughter. She continued, “This will allow them to indulge their sick fantasy of mortality. I do not believe there will be so many protesters as you imagine.”

Cedric did not argue, though whether he was in agreement or simply did not wish to pursue it further, Ayla could not tell. “I will make a pronouncement on the anniversary of Mabb’s assassination. In that time, you may keep the child’s wings disguised easily, and perhaps the Court will not link her birth as the cause for the new law.”

“They will. And they will think she is deformed,” Malachi said bitterly. “But if it is to protect the life of my child, I will bear it.”

“You would bear it, no matter the cause,” Ayla snapped, and she knew then that she was too tired, from the birth and from the meeting that had followed, to be reasonable any longer. “Thank you, Cedric. You may go and announce the birth of the Royal Heir, noting, of course, that she will be presented to all in a few weeks, when she’s of an appropriate age.”

“It would be my greatest honor, Your Majesty,” he said, bowing low before exiting her chambers.

Malachi stayed at her side, looking longingly at his daughter. As though Ayla were not there to hear it, as though it were meant for no one but himself and the child, “It is for the best,” he said quietly.

Her heart tore for him, but Ayla knew he was correct. Though it would pain him every day, disclosing the truth about her parentage would only harm Cerridwen.

The babe stirred, rustling her black feathered wings. A small, angry sound issued from her lips, but hushed as she drifted into sleep once more.

As they watched, awed by the mere presence of their daughter, Ayla found she was not as tired as she had thought. In fact, she felt she could study her child endlessly.

One

It was easy to slip from the Palace unnoticed, when you knew exactly what to do. A mistake could get you returned to precisely where you did not wish to be—confinement, boredom, the duties of a Royal Heir—but she’d learned from her mistakes in the past. Now, it was nothing at all to duck her governess and gain her freedom.

It was especially easy on this night, when so many Faeries poured in through the Palace gates that the guards would not concern themselves with the ones going out.

And this was why Cerridwen did not object to yet another royal party. She’d complained on the surface, just enough so that her compliance would not arouse suspicion. And her governess had dressed her hair and helped her into her gown, all the while ignoring the expected grumbling and protesting that she had become so used to over the past twenty years.

Twenty years. Really. Who still had a nursemaid at twenty years old? Not even the Humans kept their children as children for that long!

Twenty years, this night, and a party to celebrate it. A party to celebrate one more year that the Royal Heir was not dead. What importance was an heir, really, in a race that did not die, or, at least, did not die naturally? There would be another party like it, and another, and another, always with the same Faeries, always in the same, boring pattern. A feast, then dancing, and conversation with the few faeries she was allowed to know, all of her mother’s friends and advisors. How many evenings of her life had already been wasted in awkward chatter with Cedric, her mother’s faithful lapdog, who never said or did anything interesting, lest he offend Her Majesty? Or Malachi, who glowered and stared in the most uncomfortable way, who, it was rumored, was not even a quarter Fae, but was kept because of some bizarre devotion to her mother?

“It is not a waste,” Governess would say sagely while she pulled and pried at Cerridwen’s tangles. “If it is the will of the Gods, you will never die. You cannot waste that which is infinite.”

It did not make Cerridwen glad to know that her boredom would be infinite.

After she had been cleaned and dressed and made to look far more fine than usual for these occasions—which aroused some suspicion on her part that quickly faded when she remembered her plan to escape the party altogether—she had dutifully followed the guards that would escort her to the ball. Then she had promptly allowed herself to become separated from them by the chattering throng of arriving guests, and her escape was made.

It had not been hard to disguise her leather breeches under her gown, and when she reached an alcove, covered over by a tapestry of her mother, the Great Queene Ayla, slaying her father, the Betrayer King, she ducked behind the heavy fabric and shucked her dress, pulling on the shirt that she’d folded and hidden in her bodice. She kept her wings bound—where she was going, they did not know her as the Royal Heir to the throne of the Faeries, nor as a Faery at all. Among them, she was Human, and the ruse suited her.

The blowsy Human shirt—a ruffled, silk thing she traded with Gypsies for—would have covered her wings without their binding, but she had worn them bound since before she could remember. She felt almost naked without them secured to her back. Into her sleeve, she tucked a scrap of a mask. It would guarantee her entrance tonight, to a gathering much more desirable than the one she’d been expected to attend.

She left the dress and her shoes in the alcove. Better to go barefoot than break her neck in those flimsy slippers. She took a deep breath and slipped from her hiding place, but no one noticed her. As she wound her way through the crowd, deftly avoiding her abandoned and confused guards who stumbled, helpless, against the flow of bodies moving into the Palace, she pulled her hair over her shoulder and worked it into a loose braid, making sure to cover the wisps of antennae that sprouted from her forehead. By the time she reached the Palace gate, she could have been any Human slave being sent by their Faery master on an errand in the Lightworld.

Cerridwen spotted two such slaves following their owners into the Palace. In a time before her mother’s reign, they all said, this would never have been tolerated. Queene Ayla herself did not care for the practice, either. It brought the Fae races too close to Humans, blurred the dividing line between them. No doubt the Faeries who brought Humans into the Palace tonight would either be turned away or have their names marked down somewhere to note that they were out of favor with the Queene.

Cerridwen’s fists clenched at her sides as she marched away from the Palace. Her mother’s hypocrisy never failed to ignite fury within her. She was half Human, and yet she criticized full-blooded Faeries for consorting with them? And she kept a Darkling at her side, yet railed against the Darkworld, as well?

The flames cooled as Cerridwen realized how far she had already traveled from the Palace, and how close she was to the freedom of the Strip. Already, she could hear the sounds of it echoing through the concrete walls of her prison world. She came to the edge of the Faery Court, nodded to the guards who stood dressed in her mother’s livery, and broke into a joyous run toward the mouth of the tunnel.

The Strip was the neutral ground between the worlds of Dark and Light. A huge tunnel, reaching far over the heads of the creatures on the ground, with dwellings and places of commerce stacked on top of each other, the Strip was home to those who took no side in the ongoing war between Lightworld and Darkworld. Mostly Humans, the fascinating ancestors of Cerridwen’s mother, and, she sometimes reminded herself with pride, of herself. Gypsies, who considered themselves apart from Humans, who claimed kinship to immortal creatures long ago. Bio-mechs, still Human, but fitted with metal parts.

Then, there were those that were not so fascinating, not so much as they were repulsive or frightening. Vampires, with their thirst for the death of any mortal creature. The Gypsies that even other Gypsies would not consort with, who lured creatures away from the safety of the Strip to harvest their parts. They pulled stinking carts, hawking their wares, eyes and teeth and horns, and nameless, slimy things that no one, at least, no one that Cerridwen could think of, would want. She could not fathom why any Human would chose to live in the Underground with the very creatures their race had banished below. After the destruction of the Veil between the world of the Astral and the world of mortals, the Earth had to be shared. The Humans had taken more than their share by driving the races of the Underground into their sewers and cellars. Why some of the Humans would follow the creatures into their skyless prison, Cerridwen could not explain.

She pushed her way across the wide tunnel, toward the stand that sold sweet Human bread, and the smell reminded her that she had not brought anything to trade with. She reached to her hair, where Governess had pinned a jeweled ornament. It was worth too much to trade for simple bread, but the sticky, spiced scent teased her empty belly. Tonight, she would be generous.

A soft, tutting sound came close to her ear, and a voice whispered, “You know better than that, Cerri.”

She jumped and laughed as she turned. “Fenrick, you frightened me!”

As he always frightened her, a little. And thrilled her. He smiled, and his teeth stood out, brightly silver against the blue-black of his skin. “You should be frightened of me. You, Human, me Elf—we are, after all, mortal enemies.”

“Mortal enemies,” she agreed, good-naturedly, but she wished he would not make such jokes. They were enemies, more than he knew. Between Elf and Human, no love was lost. But the animosity between the Faery Court and the kingdom of Elves went back much farther than their confinement in the Underground.

He took the hair ornament from her hand and made a soft whistling sound as he examined it. “This looks like Faery craft. It fairly burns my skin to touch it.”

“I found it in the mouth of a tunnel to the Lightworld.” It was not a complete lie. She had found it in the Lightworld.

This impressed Fenrick; his pointed ears lifted as he smiled. “So much bravery for such a small thing! No doubt you’ll be at the front line when the great battle comes.”

The great battle. They often mocked it together, the lust for blood and war and victory that both the Lightworld and Darkworld professed at length. It was speaking out against such ideals that had gotten the Elves expelled from the Lightworld in the first years since the Great War with the Humans. And it was what had gotten Fenrick’s father expelled from the Darkworld Elves only twenty-five years previous. Fenrick had grown, as Queene Ayla had, in the hardship of the Strip.

Strange, Cerridwen thought, that it made her mother so angry and hardened at Humans, so different from Fenrick, who embraced the difficulties of his childhood and held no one unduly accountable.

Fenrick motioned to the stall owner and handed over his trade—a few water-stained packets of sugar from the Human world above, a booklet of paper scraps held together with coiled wire, and two or three small, coppery coins, also Human in origin—and waited for the thick-armed man to assess the value. He nodded, unsmiling, and broke off a large chunk of the sticky sweet bread for Fenrick.

Fenrick held up his hand. “For the Human. She was willing to part with something much more valuable for it.”

At this, the shopkeeper’s eyes widened in disbelief, and he made to pull the bread back, but Cerridwen snatched it and she and Fenrick ran laughing into the crowd at the center of the Strip.

When they stopped again, near one of the tunnels to the Darkworld, she meant to thank him for the bread. But Fenrick spoke first, and she used the opportunity to bite into the delicious Human confection.

“You look different tonight,” Fenrick said, gesturing to her face. “You’re wearing paint on your eyes. Trying to impress someone?”

She had forgotten to remove the cosmetics Governess had applied for the royal party. She swallowed carefully, the sticky bread sliding down her throat in a raw lump. Then, she put on a wicked grin, the one she had practiced in the mirror until it looked both teasing and good-humored. “Perhaps. Or several someones. The night is long.”

He took a step forward, then another, until they were so close that his chest brushed hers. His gray tongue darted over his blue-black lips, his unsettlingly yellow gaze fixed on her mouth. He leaned down, and she did not know what to do, other than to flatten against the slope of the tunnel and move the bread to her side so that he did not crush it between them. His mouth covered hers—how often had she thought of this happening in the weeks since she’d met him?—and it was exactly like, yet strangely nothing at all like, what she had imagined it would be to be kissed. She heard a small noise from her throat before she could stop it; it was a shame, she wanted to appear experienced and unaffected.