Полная версия:

The Irrational Bundle

Contents

Predictably Irrational

The Upside of Irrationality

The (Honest) Truth About Dishonesty

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Dedication

To my mentors, colleagues, and students—

who make research exciting

Contents

DEDICATION

INTRODUCTION

How an Injury Led Me to Irrationality and to the Research Described Here

CHAPTER 1 - The Truth about Relativity

Why Everything Is Relative—Even When It Shouldn’t Be

CHAPTER 2 - The Fallacy of Supply and Demand

Why the Price of Pearls—and Everything Else—Is Up in the Air

CHAPTER 3 - The Cost of Zero Cost

Why We Often Pay Too Much When We Pay Nothing

CHAPTER 4 - The Cost of Social Norms

Why We Are Happy to Do Things, but Not When We Are Paid to Do Them

CHAPTER 5 - The Power of a Free Cookie

CHAPTER 6 - The Influence of Arousal

Why Hot Is Much Hotter Than We Realize

CHAPTER 7 - The Problem of Procrastination and Self-Control

Why We Can’t Make Ourselves Do What We Want to Do

CHAPTER 8 - The High Price of Ownership

Why We Overvalue What We Have

CHAPTER 9 - Keeping Doors Open

Why Options Distract Us from Our Main Objective

CHAPTER 10 - The Effect of Expectations

Why the Mind Gets What It Expects

CHAPTER 11 - The Power of Price

Why a 50-Cent Aspirin Can Do What a Penny Aspirin Can’t

CHAPTER 12 - The Cycle of Distrust

CHAPTER 13 - The Context of Our Character, Part I

Why We Are Dishonest, and What We Can Do about It

CHAPTER 14 - The Context of Our Character, Part II

Why Dealing with Cash Makes Us More Honest

CHAPTER 15 - Beer and Free Lunches

What Is Behavioral Economics, and Where Are the Free Lunches?

THANKS

LIST OF COLLABORATORS

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND ADDITIONAL READINGS

PRAISE FOR PREDICTABLY IRRATIONAL

Introduction

How an Injury Led Me to Irrationality and

to the Research Described Here

I have been told by many people that I have an unusual way of looking at the world. Over the last 20 years or so of my research career, it’s enabled me to have a lot of fun figuring out what really influences our decisions in daily life (as opposed to what we think, often with great confidence, influences them).

Do you know why we so often promise ourselves to diet, only to have the thought vanish when the dessert cart rolls by?

Do you know why we sometimes find ourselves excitedly buying things we don’t really need?

Do you know why we still have a headache after taking a one-cent aspirin, but why that same headache vanishes when the aspirin costs 50 cents?

Do you know why people who have been asked to recall the Ten Commandments tend to be more honest (at least immediately afterward) than those who haven’t? Or why honor codes actually do reduce dishonesty in the workplace?

By the end of this book, you’ll know the answers to these and many other questions that have implications for your personal life, for your business life, and for the way you look at the world. Understanding the answer to the question about aspirin, for example, has implications not only for your choice of drugs, but for one of the biggest issues facing our society: the cost and effectiveness of health insurance. Understanding the impact of the Ten Commandments in curbing dishonesty might help prevent the next Enron-like fraud. And understanding the dynamics of impulsive eating has implications for every other impulsive decision in our lives—including why it’s so hard to save money for a rainy day.

My goal, by the end of this book, is to help you fundamentally rethink what makes you and the people around you tick. I hope to lead you there by presenting a wide range of scientific experiments, findings, and anecdotes that are in many cases quite amusing. Once you see how systematic certain mistakes are—how we repeat them again and again—I think you will begin to learn how to avoid some of them.

But before I tell you about my curious, practical, entertaining (and in some cases even delicious) research on eating, shopping, love, money, procrastination, beer, honesty, and other areas of life, I feel it is important that I tell you about the origins of my somewhat unorthodox worldview—and therefore of this book. Tragically, my introduction to this arena started with an accident many years ago that was anything but amusing.

ON WHAT WOULD otherwise have been a normal Friday afternoon in the life of an eighteen-year-old Israeli, everything changed irreversibly in a matter of a few seconds. An explosion of a large magnesium flare, the kind used to illuminate battlefields at night, left 70 percent of my body covered with third-degree burns.

The next three years found me wrapped in bandages in a hospital and then emerging into public only occasionally, dressed in a tight synthetic suit and mask that made me look like a crooked version of Spider-Man. Without the ability to participate in the same daily activities as my friends and family, I felt partially separated from society and as a consequence started to observe the very activities that were once my daily routine as if I were an outsider. As if I had come from a different culture (or planet), I started reflecting on the goals of different behaviors, mine and those of others. For example, I started wondering why I loved one girl but not another, why my daily routine was designed to be comfortable for the physicians but not for me, why I loved going rock climbing but not studying history, why I cared so much about what other people thought of me, and mostly what it is about life that motivates people and causes us to behave as we do.

During the years in the hospital following my accident, I had extensive experience with different types of pain and a great deal of time between treatments and operations to reflect on it. Initially, my daily agony was largely played out in the “bath,” a procedure in which I was soaked in disinfectant solution, the bandages were removed, and the dead particles of skin were scraped off. When the skin is intact, disinfectants create a low-level sting, and in general the bandages come off easily. But when there is little or no skin—as in my case because of my extensive burns—the disinfectant stings unbearably, the bandages stick to the flesh, and removing them (often tearing them) hurts like nothing else I can describe.

Early on in the burn department I started talking to the nurses who administered my daily bath, in order to understand their approach to my treatment. The nurses would routinely grab hold of a bandage and rip it off as fast as possible, creating a relatively short burst of pain; they would repeat this process for an hour or so until they had removed every one of the bandages. Once this process was over I was covered with ointment and with new bandages, in order to repeat the process again the next day.

The nurses, I quickly learned, had theorized that a vigorous tug at the bandages, which caused a sharp spike of pain, was preferable (to the patient) to a slow pulling of the wrappings, which might not lead to such a severe spike of pain but would extend the treatment, and therefore be more painful overall. The nurses had also concluded that there was no difference between two possible methods: starting at the most painful part of the body and working their way to the least painful part; or starting at the least painful part and advancing to the most excruciating areas.

As someone who had actually experienced the pain of the bandage removal process, I did not share their beliefs (which had never been scientifically tested). Moreover, their theories gave no consideration to the amount of fear that the patient felt anticipating the treatment; to the difficulties of dealing with fluctuations of pain over time; to the unpredictability of not knowing when the pain will start and ease off; or to the benefits of being comforted with the possibility that the pain would be reduced over time. But, given my helpless position, I had little influence over the way I was treated.

As soon as I was able to leave the hospital for a prolonged period (I would still return for occasional operations and treatments for another five years), I began studying at Tel Aviv University. During my first semester, I took a class that profoundly changed my outlook on research and largely determined my future. This was a class on the physiology of the brain, taught by professor Hanan Frenk. In addition to the fascinating material Professor Frenk presented about the workings of the brain, what struck me most about this class was his attitude to questions and alternative theories. Many times, when I raised my hand in class or stopped by his office to suggest a different interpretation of some results he had presented, he replied that my theory was indeed a possibility (somewhat unlikely, but a possibility nevertheless)—and would then challenge me to propose an empirical test to distinguish it from the conventional theory.

Coming up with such tests was not easy, but the idea that science is an empirical endeavor in which all the participants, including a new student like myself, could come up with alternative theories, as long as they found empirical ways to test these theories, opened up a new world to me. On one of my visits to Professor Frenk’s office, I proposed a theory explaining how a certain stage of epilepsy developed, and included an idea for how one might test it in rats.

Professor Frenk liked the idea, and for the next three months I operated on about 50 rats, implanting catheters in their spinal cords and giving them different substances to create and reduce their epileptic seizures. One of the practical problems with this approach was that the movements of my hands were very limited, because of my injury, and as a consequence it was very difficult for me to operate on the rats. Luckily for me, my best friend, Ron Weisberg (an avid vegetarian and animal lover), agreed to come with me to the lab for several weekends and help me with the procedures—a true test of friendship if ever there was one.

In the end, it turned out that my theory was wrong, but this did not diminish my enthusiasm. I was able to learn something about my theory, after all, and even though the theory was wrong, it was good to know this with high certainty. I always had many questions about how things work and how people behave, and my new understanding—that science provides the tools and opportunities to examine anything I found interesting—lured me into the study of how people behave.

With these new tools, I focused much of my initial efforts on understanding how we experience pain. For obvious reasons I was most concerned with such situations as the bath treatment, in which pain must be delivered to a patient over a long period of time. Was it possible to reduce the overall agony of such pain? Over the next few years I was able to carry out a set of laboratory experiments on myself, my friends, and volunteers—using physical pain induced by heat, cold water, pressure, loud sounds, and even the psychological pain of losing money in the stock market—to probe for the answers.

By the time I had finished, I realized that the nurses in the burn unit were kind and generous individuals (well, there was one exception) with a lot of experience in soaking and removing bandages, but they still didn’t have the right theory about what would minimize their patients’ pain. How could they be so wrong, I wondered, considering their vast experience? Since I knew these nurses personally, I knew that their behavior was not due to maliciousness, stupidity, or neglect. Rather, they were most likely the victims of inherent biases in their perceptions of their patients’ pain—biases that apparently were not altered even by their vast experience.

For these reasons, I was particularly excited when I returned to the burn department one morning and presented my results, in the hope of influencing the bandage removal procedures for other patients. It turns out, I told the nurses and physicians, that people feel less pain if treatments (such as removing bandages in a bath) are carried out with lower intensity and longer duration than if the same goal is achieved through high intensity and a shorter duration. In other words, I would have suffered less if they had pulled the bandages off slowly rather than with their quick-pull method.

The nurses were genuinely surprised by my conclusions, but I was equally surprised by what Etty, my favorite nurse, had to say. She admitted that their understanding had been lacking and that they should change their methods. But she also pointed out that a discussion of the pain inflicted in the bath treatment should also take into account the psychological pain that the nurses experienced when their patients screamed in agony. Pulling the bandages quickly might be more understandable, she explained, if it were indeed the nurses’ way of shortening their own torment (and their faces often did reveal that they were suffering). In the end, though, we all agreed that the procedures should be changed, and indeed, some of the nurses followed my recommendations.

My recommendations never changed the bandage removal process on a greater scale (as far as I know), but the episode left a special impression on me. If the nurses, with all their experience, misunderstood what constituted reality for the patients they cared so much about, perhaps other people similarly misunderstand the consequences of their behaviors and, for that reason, repeatedly make the wrong decisions. I decided to expand my scope of research, from pain to the examination of cases in which individuals make repeated mistakes—without being able to learn much from their experiences.

THIS JOURNEY INTO the many ways in which we are all irrational, then, is what this book is about. The discipline that allows me to play with this subject matter is called behavioral economics, or judgment and decision making (JDM).

Behavioral economics is a relatively new field, one that draws on aspects of both psychology and economics. It has led me to study everything from our reluctance to save for retirement to our inability to think clearly during sexual arousal. It’s not just the behavior that I have tried to understand, though, but also the decision-making processes behind such behavior—yours, mine, and everybody else’s. Before I go on, let me try to explain, briefly, what behavioral economics is all about and how it is different from standard economics. Let me start out with a bit of Shakespeare:

What a piece of work is a man! how noble in reason! how infinite in faculty! in form and moving how express and admirable! in action how like an angel! in apprehension how like a god! The beauty of the world, the paragon of animals. —from Act II, scene 2, of Hamlet

The predominant view of human nature, largely shared by economists, policy makers, nonprofessionals, and everyday Joes, is the one reflected in this quotation. Of course, this view is largely correct. Our minds and bodies are capable of amazing acts. We can see a ball thrown from a distance, instantly calculate its trajectory and impact, and then move our body and hands in order to catch it. We can learn new languages with ease, particularly as young children. We can master chess. We can recognize thousands of faces without confusing them. We can produce music, literature, technology, and art—and the list goes on and on.

Shakespeare is not alone in his appreciation for the human mind. In fact, we all think of ourselves along the lines of Shakespeare’s depiction (although we do realize that our neighbors, spouses, and bosses do not always live up to this standard). Within the domain of science, these assumptions about our ability for perfect reasoning have found their way into economics. In economics, this very basic idea, called rationality, provides the foundation for economic theories, predictions, and recommendations.

From this perspective, and to the extent that we all believe in human rationality, we are all economists. I don’t mean that each of us can intuitively develop complex game-theoretical models or understand the generalized axiom of revealed preference (GARP); rather, I mean that we hold the basic beliefs about human nature on which economics is built. In this book, when I mention the rational economic model, I refer to the basic assumption that most economists and many of us hold about human nature—the simple and compelling idea that we are capable of making the right decisions for ourselves.

Although a feeling of awe at the capability of humans is clearly justified, there is a large difference between a deep sense of admiration and the assumption that our reasoning abilities are perfect. In fact, this book is about human irrationality—about our distance from perfection. I believe that recognizing where we depart from the ideal is an important part of the quest to truly understand ourselves, and one that promises many practical benefits. Understanding irrationality is important for our everyday actions and decisions, and for understanding how we design our environment and the choices it presents to us.

My further observation is that we are not only irrational, but predictably irrational—that our irrationality happens the same way, again and again. Whether we are acting as consumers, businesspeople, or policy makers, understanding how we are predictably irrational provides a starting point for improving our decision making and changing the way we live for the better.

This leads me to the real “rub” (as Shakespeare might have called it) between conventional economics and behavioral economics. In conventional economics, the assumption that we are all rational implies that, in everyday life, we compute the value of all the options we face and then follow the best possible path of action. What if we make a mistake and do something irrational? Here, too, traditional economics has an answer: “market forces” will sweep down on us and swiftly set us back on the path of righteousness and rationality. On the basis of these assumptions, in fact, generations of economists since Adam Smith have been able to develop far-reaching conclusions about everything from taxation and health-care policies to the pricing of goods and services.

But, as you will see in this book, we are really far less rational than standard economic theory assumes. Moreover, these irrational behaviors of ours are neither random nor senseless. They are systematic, and since we repeat them again and again, predictable. So, wouldn’t it make sense to modify standard economics, to move it away from naive psychology (which often fails the tests of reason, introspection, and—most important—empirical scrutiny)? This is exactly what the emerging field of behavioral economics, and this book as a small part of that enterprise, is trying to accomplish.

AS YOU WILL see in the pages ahead, each of the chapters in this book is based on a few experiments I carried out over the years with some terrific colleagues (at the end of the book, I have included short biographies of my amazing collaborators). Why experiments? Life is complex, with multiple forces simultaneously exerting their influences on us, and this complexity makes it difficult to figure out exactly how each of these forces shapes our behavior. For social scientists, experiments are like microscopes or strobe lights. They help us slow human behavior to a frame-by-frame narration of events, isolate individual forces, and examine those forces carefully and in more detail. They let us test directly and unambiguously what makes us tick.

There is one other point I want to emphasize about experiments. If the lessons learned in any experiment were limited to the exact environment of the experiment, their value would be limited. Instead, I would like you to think about experiments as an illustration of a general principle, providing insight into how we think and how we make decisions—not only in the context of a particular experiment but, by extrapolation, in many contexts of life.

In each chapter, then, I have taken a step in extrapolating the findings from the experiments to other contexts, attempting to describe some of their possible implications for life, business, and public policy. The implications I have drawn are, of course, just a partial list.

To get real value from this, and from social science in general, it is important that you, the reader, spend some time thinking about how the principles of human behavior identified in the experiments apply to your life. My suggestion to you is to pause at the end of each chapter and consider whether the principles revealed in the experiments might make your life better or worse, and more importantly what you could do differently, given your new understanding of human nature. This is where the real adventure lies.

And now for the journey.

CHAPTER 1

The Truth about Relativity

Why Everything Is Relative—Even

When It Shouldn’t Be

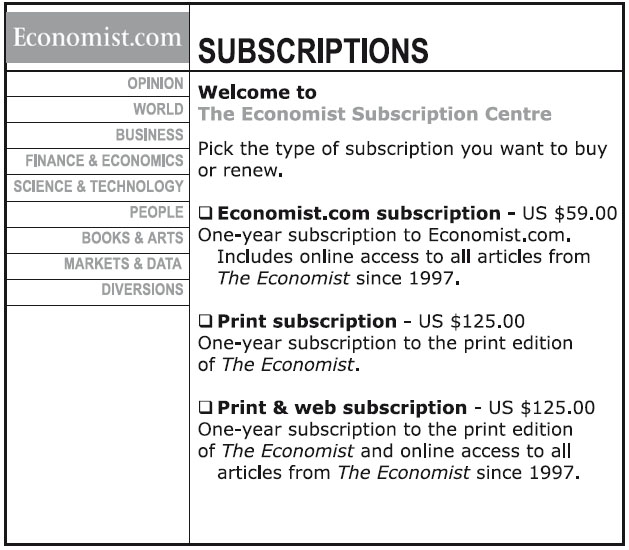

One day while browsing the World Wide Web (obviously for work—not just wasting time), I stumbled on the following ad, on the Web site of a magazine, the Economist.

I read these offers one at a time. The first offer—the Internet subscription for $59—seemed reasonable. The second option—the $125 print subscription—seemed a bit expensive, but still reasonable.

But then I read the third option: a print and Internet subscription for $125. I read it twice before my eye ran back to the previous options. Who would want to buy the print option alone, I wondered, when both the Internet and the print subscriptions were offered for the same price? Now, the print-only option may have been a typographical error, but I suspect that the clever people at the Economist’s London offices (and they are clever—and quite mischievous in a British sort of way) were actually manipulating me. I am pretty certain that they wanted me to skip the Internet-only option (which they assumed would be my choice, since I was reading the advertisement on the Web) and jump to the more expensive option: Internet and print.

But how could they manipulate me? I suspect it’s because the Economist’s marketing wizards (and I could just picture them in their school ties and blazers) knew something important about human behavior: humans rarely choose things in absolute terms. We don’t have an internal value meter that tells us how much things are worth. Rather, we focus on the relative advantage of one thing over another, and estimate value accordingly. (For instance, we don’t know how much a six-cylinder car is worth, but we can assume it’s more expensive than the four-cylinder model.)

In the case of the Economist, I may not have known whether the Internet-only subscription at $59 was a better deal than the print-only option at $125. But I certainly knew that the print-and-Internet option for $125 was better than the print-only option at $125. In fact, you could reasonably deduce that in the combination package, the Internet subscription is FREE! “It’s a bloody steal—go for it, governor!” I could almost hear them shout from the riverbanks of the Thames. And I have to admit, if I had been inclined to subscribe I probably would have taken the package deal myself. (Later, when I tested the offer on a large number of participants, the vast majority preferred the Internet-and-print deal.)