Полная версия:

The One and Only Ivan

Dedication

For Julia

Epigraph

It is never too late to be

what you might have been.

—George Eliot

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Hello

Names

Patience

How I Look

The Exit 8 Big Top Mall and Video Arcade

The Littlest Big Top on Earth

Gone

Artists

Shapes in Clouds

Imagination

The Loneliest Gorilla in the World

TV

The Nature Show

Stella

Stella’s Trunk

A Plan

Bob

Wild

Picasso

Three Visitors

My Visitors Return

Sorry

Julia

Drawing Bob

Bob and Julia

Mack

Not Sleepy

The Beetle

Change

Guessing

Jambo

Lucky

Arrival

Stella Helps

Old News

Tricks

Introductions

Stella and Ruby

Home of the One and Only Ivan

Art Lesson

Treat

Elephant Jokes

Children

The Parking Lot

Ruby’s Story

A Hit

Worry

The Promise

Knowing

Five Men

Comfort

Crying

The One and Only Ivan

Once Upon A Time

The Grunt

Mud

Protector

A Perfect Life

The End

Vine

The Temporary Human

Hunger

Still Life

Punishment

Babies

Beds

My Place

Nine Thousand Eight Hundred and Seventy-Six Days

A Visit

A New Beginning

Poor Mack

Colours

A Bad Dream

The Story

How

Remembering

What They Did

Something Else to Buy

Another Ivan

Days

Nights

Project

Not Right

Going Nowhere

Bad Guys

Ad

Imagining

Not-Tag

One More Thing

The Seven O’clock Show

Twelve

H

Nervous

Showing Julia

More Paintings

Chest Beating

Angry

Puzzle Pieces

Finally

The Next Morning

Mad Human

Phone Call

A Star Again

The Ape Artist

Interview

The Early News

Signs on Sticks

Protesters

Check Marks

Free Ruby

New Box

Training

Poking and Prodding

No Painting

More Boxes

Goodbye

Click

An Idea

Respect

Photo

Leaving

Good Boy

Moving

Awakening

Missing

Food

Not Famous

Something in the Air

A New TV

The Family

Excited

What I See

Still There

Watching

She

Door

Wondering

Ready

Outside at Last

Oops

What It Was Like

Pretending

Nest

More TV

It

Romance

More About Romance

Grooming

Talk

The Top of the Hill

The Wall

Safe

Silverback

Glossary

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Hello

I am Ivan. I am a gorilla.

It’s not as easy as it looks.

Names

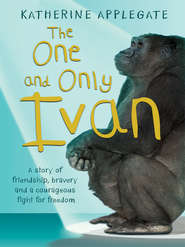

People call me the Freeway Gorilla. The Ape at Exit 8. The One and Only Ivan, Mighty Silverback.

The names are mine, but they’re not me. I am Ivan, just Ivan, only Ivan.

Humans waste words. They toss them like banana peels and leave them to rot.

Everyone knows the peels are the best part.

I suppose you think gorillas can’t understand you. Of course, you also probably think we can’t walk upright.

Try knuckle walking for an hour. You tell me: which way is more fun?

Patience

I’ve learned to understand human words over the years, but understanding human speech is not the same as understanding humans.

Humans speak too much. They chatter like chimps, crowding the world with their noise even when they have nothing to say.

It took me some time to recognise all those human sounds, to weave words into things. But I was patient.

Patient is a useful way to be when you’re an ape.

Gorillas are as patient as stones. Humans, not so much.

How I Look

I used to be a wild gorilla, and I still look the part.

I have a gorilla’s shy gaze, a gorilla’s sly smile. I wear a snowy saddle of fur, the uniform of a silverback. When the sun warms my back, I cast a gorilla’s majestic shadow.

In my size humans see a test of themselves. They hear fighting words on the wind, when all I’m thinking is how the late-day sun reminds me of a ripe nectarine.

I’m mightier than any human, four hundred pounds of pure power. My body looks made for battle. My arms, outstretched, span taller than the tallest human.

My family tree spreads wide as well. I am a great ape, and you are a great ape, and so are chimpanzees and orangutans and bonobos, all of us distant and distrustful cousins.

I know this is troubling.

I too find it hard to believe there is a connection across time and space, linking me to a race of ill-mannered clowns.

Chimps. There’s no excuse for them.

The Exit 8 Big Top Mall and Video Arcade

I live in a human habitat called the Exit 8 Big Top Mall and Video Arcade. We are conveniently located off I-95, with shows at two, four and seven, 365 days a year.

Mack says that when he answers the trilling telephone.

Mack works here at the mall. He is the boss.

I work here too. I am the gorilla.

At the Big Top Mall, a creaky-music carousel spins all day, and monkeys and parrots live amid the merchants. In the middle of the mall is a ring with benches where humans can sit on their rumps while they eat soft pretzels. The floor is covered with sawdust made of dead trees.

My domain is at one end of the ring. I live here because I am too much gorilla and not enough human.

Stella’s domain is next to mine. Stella is an elephant. She and Bob, who is a dog, are my dearest friends.

At present, I do not have any gorilla friends.

My domain is made of thick glass and rusty metal and rough cement. Stella’s domain is made of metal bars. The sun bears’ domain is wood; the parrots’ is wire mesh.

Three of my walls are glass. One of them is cracked, and a small piece, about the size of my hand, is missing from its bottom corner. I made the hole with a baseball bat Mack gave me for my sixth birthday. After that he took the bat away, but he let me keep the baseball that came with it.

A jungle scene is painted on one of my domain walls. It has a waterfall without water and flowers without scent and trees without roots. I didn’t paint it, but I enjoy the way the shapes flow across my wall, even if it isn’t much of a jungle.

I am lucky my domain has three windowed walls. I can see the whole mall and a bit of the world beyond: the frantic pinball machines, the pink billows of cotton candy, the vast and treeless parking lot.

Beyond the lot is a freeway where cars stampede without end. A giant sign at its edge beckons them to stop and rest like gazelles at a watering hole.

The sign is faded, the colours bleeding, but I know what it says. Mack read its words aloud one day: “COME TO THE EXIT 8 BIG TOP MALL AND VIDEO ARCADE, HOME OF THE ONE AND ONLY IVAN, MIGHTY SILVERBACK!”

Sadly, I cannot read, although I wish I could. Reading stories would make a fine way to fill my empty hours.

Once, however, I was able to enjoy a book left in my domain by one of my keepers.

It tasted like termite.

The freeway billboard has a drawing of Mack in his clown clothes and Stella on her hind legs and an angry animal with fierce eyes and unkempt hair.

That animal is supposed to be me, but the artist made a mistake. I am never angry.

Anger is precious. A silverback uses anger to maintain order and warn his troop of danger. When my father beat his chest, it was to say, Beware, listen, I am in charge. I am angry to protect you, because that is what I was born to do.

Here in my domain, there is no one to protect.

The Littlest Big Top on Earth

My neighbours here at the Big Top Mall know many tricks. They are an educated lot, more accomplished than I.

One of my neighbours plays baseball, although she is a chicken. Another drives a fire truck, although he is a rabbit.

I used to have a neighbour, a sleek and thoughtful seal, who could balance a ball on her nose from dawn till dusk. Her voice was like the throaty bark of a dog chained outside on a cold night.

Children wished on pennies and tossed them into her plastic pool. They glowed on the bottom like flat copper stones.

The seal was hungry one day, or bored, perhaps, so she ate one hundred pennies.

Mack said she’d be fine.

He was mistaken.

Mack calls our show “The Littlest Big Top on Earth”. Every day at two, four and seven, humans fan themselves, drink sodas, applaud. Babies wail. Mack, dressed like a clown, pedals a tiny bike. A dog named Snickers rides on Stella’s back. Stella sits on a stool.

It is a very sturdy stool.

I don’t do any tricks. Mack says it’s enough for me to be me.

Stella told me that some circuses move from town to town. They have humans who dangle on ropes twining from the tops of tents. They have grumbling lions with gleaming teeth and a snaking line of elephants, each clutching the limp tail in front of her. The elephants look far off into the distance so they won’t see the humans who want to see them.

Our circus doesn’t migrate. We sit where we are, like an old beast too tired to push on.

After our show, humans forage through the stores. A store is where humans buy things they need to survive. At the Big Top Mall, some stores sell new things, things like balloons and T-shirts and caps to cover the gleaming heads of humans. Some stores sell old things, things that smell dusty and damp and long-forgotten.

All day, I watch humans scurry from store to store. They pass their green paper, dry as old leaves and smelling of a thousand hands, back and forth and back again.

They hunt frantically, stalking, pushing, grumbling. Then they leave, clutching bags filled with things – bright things, soft things, big things – but no matter how full the bags, they always come back for more.

Humans are clever indeed. They spin pink clouds you can eat. They build domains with flat waterfalls.

But they are lousy hunters.

Gone

Some animals live privately, unwatched, but that is not my life.

My life is flashing lights and pointing fingers and uninvited visitors. Inches away, humans flatten their little hands against the wall of glass that separates us.

The glass says you are this and we are that and that is how it will always be.

Humans leave their fingerprints behind, sticky with candy, slick with sweat. Each night a weary man comes to wipe them away.

Sometimes I press my nose against the glass. My noseprint, like your fingerprint, is the first and last and only one.

The man wipes the glass and then I am gone.

Artists

Here in my domain, I do not have much to do. You can only throw so many me-balls at humans before you get bored.

A me-ball is made by rolling up dung until it’s the size of a small apple, then letting it dry. I always keep a few on hand.

For some reason, my visitors never seem to carry any.

In my domain, I have a tyre swing, a baseball, a tiny plastic pool filled with dirty water, and even an old TV.

I have a stuffed toy gorilla too. Julia, the daughter of the weary man who cleans the mall each night, gave it to me.

The gorilla has empty eyes and floppy limbs, but I sleep with it every night. I call it Not-Tag.

Tag was my twin sister’s name.

Julia is ten years old. She has hair like black glass and a wide, half-moon smile. She and I have a lot in common. We are both great apes, and we are both artists.

It was Julia who gave me my first crayon, a stubby blue one, slipped through the broken spot in my glass along with a folded piece of paper.

I knew what to do with it. I’d watched Julia draw. When I dragged the crayon across the paper, it left a trail in its wake like a slithering blue snake.

Julia’s drawings are wild with colour and movement. She draws things that aren’t real: clouds that smile and cars that swim. She draws until her crayons break and her paper rips. Her pictures are like pieces of a dream.

I can’t draw dreamy pictures. I never remember my dreams, although I sometimes awaken with my fists clenched and my heart hammering.

My drawings seem pale and timid next to Julia’s. She draws ideas in her head. I draw things in my cage, the simple items that fill my days: an apple core, a banana peel, a candy wrapper. (I often eat my subjects before I draw them.)

But even though I draw the same things over and over again, I never get bored with my art. When I’m drawing, that’s all I think about. I don’t think about where I am, about yesterday or tomorrow. I just move my crayons across the paper.

Humans don’t always seem to recognise what I’ve drawn. They squint, cock their heads, murmur. I’ll draw a banana, a perfectly lovely banana, and they’ll say, “It’s a yellow airplane!” or “It’s a duck without wings!”

That’s all right. I’m not drawing for them. I’m drawing for me.

Mack soon realised that people will pay for a picture made by a gorilla, even if they don’t know what it is. Now I draw every day. My works sell for twenty dollars apiece (twenty-five with frame) at the gift shop near my domain.

If I get tired and need a break, I eat my crayons.

Shapes in Clouds

I think I’ve always been an artist.

Even as a baby, still clinging to my mother, I had an artist’s eye. I saw shapes in the clouds, and sculptures in the tumbled stones at the bottom of a stream. I grabbed at colours – the crimson flower just out of reach, the ebony bird streaking past.

I don’t remember much about my early life, but I do remember this: Whenever I got the chance, I would dip my fingers into cool mud and use my mother’s back for a canvas.

She was a patient soul, my mother.

Imagination

Someday, I hope I can draw the way Julia draws, imagining worlds that don’t yet exist.

I know what most humans think. They think gorillas don’t have imaginations. They think we don’t remember our pasts or ponder our futures.

Come to think of it, I suppose they have a point. Mostly I think about what is, not what could be.

I’ve learned not to get my hopes up.

The Loneliest Gorilla in the World

When the Big Top Mall was first built, it smelled of new paint and fresh hay, and humans came to visit from morning till night. They drifted past my domain like logs on a lazy river.

Lately, a day might go by without a single visitor. Mack says he’s worried. He says I’m not cute any more. He says, “Ivan, you’ve lost your magic, old guy. You used to be a hit.”

It’s true that some of my visitors don’t linger the way they used to. They stare through the glass, they cluck their tongues, they frown while I watch my TV.

“He looks lonely,” they say.

Not long ago, a little boy stood before my glass, tears streaming down his smooth red cheeks. “He must be the loneliest gorilla in the world,” he said, clutching his mother’s hand.

At times like that, I wish humans could understand me the way I can understand them.

It’s not so bad, I wanted to tell the little boy. With enough time, you can get used to almost anything.

TV

My visitors are often surprised when they see the TV Mack put in my domain. They seem to find it odd, the sight of a gorilla staring at tiny humans in a box.

Sometimes I wonder, though: Isn’t the way they stare at me, sitting in my tiny box, just as strange?

My TV is old. It doesn’t always work, and sometimes days will go by before anyone remembers to turn it on.

I’ll watch anything, but I’m particularly fond of cartoons, with their bright jungle colours. I especially enjoy it when someone slips on a banana peel.

Bob, my dog friend, loves TV almost as much as I do. He prefers to watch professional bowling and cat-food commercials.

Bob and I have seen many romance movies too. In a romance there is much hugging and sometimes face licking.

I have yet to see a single romance starring a gorilla.

We also enjoy old western movies. In a western, someone always says, “This town ain’t big enough for the both of us, Sheriff.” In a western, you can tell who the good guys are and who the bad guys are, and the good guys always win.

Bob says westerns are nothing like real life.

The Nature Show

I have been in my domain for nine thousand eight hundred and fifty-five days.

Alone.

For a while, when I was young and foolish, I thought I was the last gorilla on earth.

I tried not to dwell on it. Still, it’s hard to stay upbeat when you think there are no more of you.

Then one night, after I watched a movie about men in black hats with guns and feeble-minded horses, a different show came on.

It was not a cartoon, not a romance, not a western.

I saw a lush forest. I heard birds murmuring. The grass moved. The trees rustled.

Then I saw him. He was bit threadbare and scrawny, and not as good-looking as I am, to be honest. But sure enough, he was a gorilla.

As suddenly as he’d appeared, the gorilla vanished, and in his place was a scruffy white animal called, I learned, a polar bear, and then a chubby water creature called a manatee, and then another animal, and another.

All night I sat wondering about the gorilla I’d glimpsed. Where did he live? Would he ever come to visit? If there was a he somewhere, could there be a she as well?

Or was it just the two of us in all the world, trapped in our own separate boxes?

Stella

Stella says she is sure I will see another real, live gorilla someday, and I believe her because she is even older than I and has eyes like black stars and knows more than I will ever know.

Stella is a mountain. Next to her I am a rock, and Bob is a grain of sand.

Every night, when the stores close and the moon washes the world with milky light, Stella and I talk.

We don’t have much in common, but we have enough. We are huge and alone and we both love yogurt raisins.

Sometimes Stella tells stories of her childhood, of leafy canopies hidden by mist and the busy songs of flowing water. Unlike me, she recalls every detail of her past.

Stella loves the moon, with its untroubled smile. I love the feel of the sun on my belly.

She says, “It is quite a belly, my friend,” and I say, “Thank you, and so is yours.”

We talk, but not too much. Elephants, like gorillas, do not waste words.

Stella used to perform in a large and famous circus, and she still does some of those tricks for our show. During one stunt, Stella stands on her hind legs while Snickers jumps on her head.

It’s hard to stand on your hind legs when you weigh more than forty men.

If you are a circus elephant and you stand on your hind legs while a dog jumps on your head, you get a treat. If you do not, the claw-stick comes swinging.

Elephant hide is thick as bark on an ancient tree, but a claw-stick can pierce it like a leaf.

Once Stella saw a trainer hit a bull elephant with a claw-stick. A bull is like a silverback, noble, contained, calm like a cobra is calm. When the claw-stick caught in the bull’s flesh, he tossed the trainer into the air with his tusk.

The man flew, Stella said, like an ugly bird. She never saw the bull again.

Stella’s Trunk

Stella’s trunk is a miracle. She can pick up a single peanut with elegant precision, tickle a passing mouse, tap the shoulder of a dozing keeper.

Her trunk is remarkable, but still it can’t unlatch the door of her tumble-down domain.

Circling Stella’s legs are long-ago scars from the chains she wore as a youth: her bracelets, she calls them. When she worked at the famous circus Stella had to balance on a pedestal for her most difficult trick. One day, she fell off and injured her foot. When she went lame and lagged behind the other elephants, the circus sold her to Mack.

Stella’s foot never healed completely. She limps when she walks, and sometimes her foot gets infected when she stands in one place for too long.

Last winter, Stella’s foot swelled to twice its normal size. She had a fever, and she lay on the damp, cold floor of her domain for five days.

They were very long days.

Even now, I’m not sure she’s completely better. She never complains, though, so it’s hard to know.

At the Big Top Mall, no one bothers with iron shackles. A bristly rope tied to a bolt in the floor is all that’s required.

“They think I’m too old to cause trouble,” Stella says.

“Old age,” she says, “is a powerful disguise.”

A Plan

It’s been two days since anyone’s come to visit. Mack is in a bad mood. He says we are losing money hand over fist. He says he is going to sell the whole lot of us.

When Thelma, a blue and yellow macaw, demands “Kiss me, big boy,” for the third time in ten minutes, Mack throws a soda can at her. Thelma’s wings are clipped so that she can’t fly, but she still can hop. She leaps aside just in the nick of time. “Pucker up!” she says with a shrill whistle.

Mack stomps to his office and slams the door shut.

I wonder if my visitors have grown tired of me. Maybe if I learn a trick or two, it would help.

Humans do seem to enjoy watching me eat. Luckily, I am always hungry. I am a gifted eater.

A silverback must eat forty-five pounds of food a day if he wants to stay a silverback. Forty-five pounds of fruit and leaves and seeds and stems and bark and vines and rotten wood.

Also, I enjoy the occasional insect.

I am going to try to eat more. Maybe then we will get more visitors. Tomorrow I will eat fifty pounds of food. Maybe even fifty-five.

That should make Mack happy.

Bob

I explain my plan to Bob.

“Ivan,” he says, “trust me on this one: the problem is not your appetite.” He hops on to my chest and licks my chin, checking for leftovers.

Bob is a stray, which means he does not have a permanent address. He is so speedy, so wily, that mall workers long ago gave up trying to catch him. Bob can sneak into cracks and crevices like a tracked rat. He lives well off the ends of hot dogs he pulls from the trash. For dessert, he laps up spilled lemonade and splattered ice-cream cones.