скачать книгу бесплатно

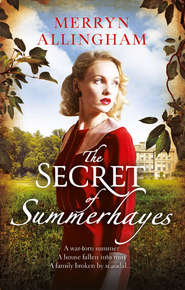

The Secret of Summerhayes

Merryn Allingham

A war-torn summerA house fallen into ruinA family broken apart by scandal…Summer 1944: Bombed out by the blitz, Bethany Merston takes up a post as companion to elderly Alice Summer, last remaining inhabitant of the dilapidated and crumbling Summerhayes estate. Now a shadow of its former glory; most of the rooms have been shut up, the garden is overgrown and the whole place feels as unwelcoming as the family themselves.Struggling with the realities of war, Alice is plagued by anonymous letters and haunting visions of her old household. At first, Beth tries to convince her it’s all in her mind but soon starts to unravel the mysteries surrounding the aristocratic family’s past.An evocative and captivating tale, The Secret of Summerhayes tells of dark secrets, almost-forgotten scandals and a household teetering on the edge of ruin.

Also by Merryn Allingham (#ulink_a7c74260-9e29-5440-8575-07532dbcdff4)

The Crystal Cage

The Girl from Cobb Street

The Nurse’s War

Daisy’s Long Road Home

The Buttonmaker’s Daughter

MERRYN ALLINGHAM was born into an army family and spent her childhood on the move. Unsurprisingly, it gave her itchy feet and in her twenties she escaped from an unloved secretarial career to work as cabin crew and see the world. The arrival of marriage, children and cats meant a more settled life in the south of England where she’s lived ever since. It also gave her the opportunity to go back to ‘school’ and eventually teach at university.

Merryn has always loved books that bring the past to life, so when she began writing herself the novels had to be historical. She finds the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries fascinating eras to research and her first book, The Crystal Cage, had as its background the London of 1851. The Daisy’s War trilogy followed, set in India and London during the 1930s and 40s.

Her latest novels explore two pivotal moments in the history of Britain. The Buttonmaker’s Daughter is set in Sussex in the summer of 1914 as the First World War looms ever nearer and its sequel, The Secret of Summerhayes, thirty years later in the summer of 1944 when D-Day led to eventual victory in the Second World War. Along with the history, of course, there is plenty of mystery and romance to keep readers intrigued.

If you would like to keep in touch with Merryn, sign up for her newsletter at www.merrynallingham.com (http://www.merrynallingham.com)

Contents

Cover (#uc47d1b9d-47fa-52f1-85be-d5bf8bda2b2b)

Also by Merryn Allingham (#ulink_579f2ba0-125d-52f5-b568-8f00384f4edd)

About the Author (#u843dc84e-6eb7-5dd4-bacf-880097b01e35)

Title Page (#u586210b9-9059-558e-9f96-0ebcbe4ed926)

Chapter One (#ulink_3dd70b32-151c-5a9e-a108-20cb4ba817f8)

Chapter Two (#ulink_c09d8395-0ace-5485-b9aa-100126940357)

Chapter Three (#ulink_230128f0-1211-5709-8233-0f346e508427)

Chapter Four (#ulink_b1558f4a-930c-597a-914c-c444f7593f91)

Chapter Five (#ulink_86691283-bdfc-5b26-9159-592ca4cdb900)

Chapter Six (#ulink_ca8395aa-7236-5b70-af86-a58252746aed)

Chapter Seven (#ulink_88559168-ace3-541e-aecd-3058d6196a76)

Chapter Eight (#ulink_3254eac0-9b20-5495-ada5-7c4be692e203)

Chapter Nine (#ulink_14d01a13-d906-55af-821f-f94dc78f63cd)

Chapter Ten (#ulink_b39dd17a-b374-5b05-ba9f-d6ee4870501b)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_4778e84d-11c9-5a1d-9077-5c55c3878513)

Sussex, England, late April 1944

Something about the scene caught at him, some memory he couldn’t grasp. Behind him the tangled mass of alders – they were alders, weren’t they? – but before his eyes, a landscape he must have read about, or perhaps dreamt. He’d never been here before, that was certain. The last two years had been spent miles away, and though since January his regiment had been moving from camp to camp, this was the furthest west they had come. He pushed past the last few branches and received another scratch to add to all the others. The trees had long ago grown together to form an almost impenetrable barrier. The old fellow who’d given him a lift had heard the word Summerhayes and dropped him at what must have been the rear entrance. He should have stopped at the broken brick columns and found another way in, walked around the perimeter wall until he came to a main entrance. That was probably in the same ramshackle state, but the tanks would have bulldozed a path by now and the going would be easier. Very much easier. He should turn back.

But he didn’t. Something made him push on, that dream perhaps, a misty image he carried with him. Now that he was clear of the trees, he could see more than a few feet ahead. He appeared to be standing on what had once been a paved terrace. Beneath the heaps of dead winter leaves, he glimpsed terracotta. A Mediterranean colour, out of place in an English garden, or even an English wilderness. It appeared to circle what must have once been a lake but was now stagnant water, carpeted from one side to the other with giant water lilies. The air was slightly sour; it smelt of mud, smelt of must. In the centre of the lake, the remains of a statue, broken and chipped, rose strangely from out of the rampant vegetation. It was as though, wounded and maimed, it was trying to escape. Something about the place held him fast. He stood for a long time, feeling his pulse gradually slacken, the rhythm of his heart seeming to align itself to that of the earth. What kind of craziness was that? He shook his head in disbelief and as quickly as the heavy backpack allowed, made his way to an archway in one corner of the clearing. The exit, he imagined, but it was as overgrown as everything else, its laurel leaves a dense mass.

He looked back before shouldering through this new obstruction. On one side of the lake, there had been a small summerhouse but its roof was smashed and a giant vine had weaved its way through the corpse. Directly across the water, there had been another building, and he could see immediately that it was one built to impressive proportions. Now all that remained of it were two or three shattered columns and the raised dais they stood upon. It seemed to have been some kind of temple, for the pediment had crashed to the ground and taken several pillars with it. Did English gardens have temples? He supposed they must. In that instant, the sun emerged from a passing cloud and glanced across the remaining pillars, its rays flashing pure crystal. He gave a low whistle. The building was of marble. Once upon a time, this had been a wealthy place.

With some difficulty he pushed through the strangled archway, but was immediately brought up short. He was facing what appeared to be an acre of grass and brambles, at least six feet in height, and with no path in sight. Here and there huge palm trees rose out of the oversized meadow, spreading their arms in a riot of tough, sword-like prongs or half-tumbled to the ground, their hairy trunks dank and rotted. Between the palms, gigantic ferns hovered like green spiders inflated to monstrous size. He would never find his way through this, and he was running out of time. By now everyone would have settled their billets, his men would be waiting for orders and Eddie would be wondering where the hell he’d got to. His pal would be brewing coffee and if he hadn’t had to do that damned detour, he’d be drinking it alongside him. It had been a waste of time in any case; when he’d got to Aldershot, he’d found the regiment’s surplus equipment had already been despatched without any help from him. The logistics of constantly moving were a nightmare and he hoped this was the last camp they’d pitch before the push into Europe.

For months the regiment had been gradually inching along the south coast, practising manoeuvres as they went. It was common knowledge that an invasion this summer was on the cards; he was pretty sure it would only be a matter of weeks. He prayed, they all prayed, there’d be no repeat of the Dieppe debacle. The planners had called it a reconnaissance, his fellow soldiers a disaster. The element of surprise had been lost. A German navy patrol had spotted the Canadians and alerted the batteries on shore. His countrymen had faced murderous fire within a few yards of their landing craft – over three thousand killed, maimed or captured, and fewer than half their number returning to tell their story. He’d lost friends in that attack and mourned them still.

He pushed on, striking due north in the hope of finding some sign of men and machines, using his knife to hack a narrow path through grass that grew to the height of a small hut. It was hot and steamy and pungent. The backpack weighed heavier with each minute and though it was only April, the sun was unusually bright and he was forced to push back the fall of hair from his forehead and wipe a trickle of sweat from his face. But after fifteen minutes, he’d progressed just fifty yards. He stood still and gazed across at the tangle of grass and palms and ferns. He’d had enough.

He turned to go back the way he’d come. It was only then that he became aware he was not alone. Through the long stalks of grass, a pair of eyes peered at him, fixing him in an unnerving gaze. It was as though the grass itself was deciding whether he were friend or foe.

Then a small voice broke the silence. ‘Are you lost?’

Chapter Two (#ulink_ddc5271f-44f0-5eab-8ac0-157051da5ab8)

Bethany Merston turned into the drive of Summerhayes and saw the Canadian army had well and truly arrived. The estate had been a military base for years now, the house and grounds requisitioned at the outbreak of war, but this was altogether a far larger invasion. For several days past the clatter of men and trucks had been a noisy backdrop to life. The advance party, she’d guessed, but now it appeared the entire battalion had taken possession of the estate. And the men on either side of the drive – parking jeeps, carrying supplies, marching briskly between temporary shelters – were larger, too. They made the local population look weaklings. Unlike the natives, they’d not endured years of rationing, nor an interwar period of poor nourishment and intermittent work.

This morning, as the first trucks had rolled in, she’d walked to the village for whatever supplies she could forage, but returned with little. Neither she nor Alice nor Mr Ripley would get too fat on what her solitary bag contained. But at least she’d managed to buy cocoa powder for Alice’s night-time drink. Only a few ounces, and it would have to be sweetened with the honey she’d bartered for last week, but it would keep the old lady going a little longer. If Mrs Summer had cocoa at bedtime, she slept well. Even the drone of German bombers flying low towards London didn’t disturb her, and that meant that Beth slept well, too.

She crunched her way along the gravel drive taking care to avoid the whirlwind of activity, but walking as swiftly as she could. If the noise had penetrated to the upstairs apartment, Mrs Summer would be anxious. On reflection, her working life had altered little except to exchange the care of thirty small bodies for one elderly one. Looking after an old lady wasn’t that much different from looking after a young child. Both needed reassurance and practical help; both blossomed with kindness.

A few months ago a stray bomb falling on Quilter Street had obliterated the Bethnal Green school where she worked. It was a miracle it had happened at night and there had been no casualties, but it had left her jobless. Thank goodness, then, for the advert in The Lady. Within weeks she’d found the post at Summerhayes, though it was one she had never imagined for herself. But in wartime needs must, and a war spent here was as good as anywhere. The Sussex countryside was beautiful and the estate, though fallen into disrepair, still retained a little of its former glory. Above all the place was tranquil and, coming from a ravaged London, she was grateful for its peace, though now the Canadian army had arrived in force, peace might be a lost treasure.

One or two of the soldiers glanced curiously at her as she made her way to the side door, but she managed to slip into the house without attracting too much attention. She slid past the drawing room, catching a brief glimpse of several officers’ caps on the mantel shelf, past the dining room where desks were being shifted and typewriters arranged, and then up the stairs to the apartment she shared with Alice, all that was left for the old lady of the magnificent Arts and Crafts mansion she had once inhabited. Almost certainly the senior officers would be billeted in the house, while junior officers and their men were consigned to tents in the grounds. Or maybe this time they would build more permanent structures, though she doubted it. Rumours of invasion were rife and the battalion was unlikely to stay long.

Everyone was aware that the military had increased hugely of late, a steady flow of army units turning into a flood. The whole of Sussex had become a vast, armed camp. Mortars and artillery had long been familiar sounds on the South Downs, along with the screech and clatter of tank tracks in the surrounding villages, but now you couldn’t walk a country lane without being passed by a ten-ton truck or a speeding jeep. On her last visit to the village, she’d had to jump into a ditch to avoid a rogue tank trundling down the narrowest of roads and filling it from hedgerow to hedgerow.

She had reached the cramped staircase to the apartment when the wailing hit her. Mrs Summer! She raced up the remaining stairs, fumbling for the key as she went. The new girl from the village had begun work today and Beth had thought it safe to disappear for an hour and leave her to keep an eye. Molly had been cleaning the small kitchen when she’d left, but when she finally burst through the door, the girl was nowhere to be seen. Instead, Beth found the old lady in the sitting room, hunched into the corner of a wing chair, her body rocking back and forth to the rhythm of her cries. Beth glanced wildly around and her heart sank. A white envelope. Another letter. Ripley had been told to make sure that no such letters were delivered to his mistress, except via Bethany. But the former footman was an old man, a pensioner now rather than a worker, and he would be lying down on his bed for a morning nap. She had given the same instructions to Molly before she left, but the girl had clearly forgotten.

‘Mrs Summer, it’s all right, I’m here.’

She flung the bag to the floor, unmindful that their week’s rations would be squashed out of recognition, then knelt down at the elderly woman’s side and took her in her arms, holding her close and trying to calm the demented rocking. Very gradually, Alice became still and the sobs ceased. Beth stroked the thin, grey hair into place and fished in her pocket for a handkerchief to dab tears from the deeply lined cheeks.

‘But it’s not all right.’ Alice looked up, her eyes pools of sadness. ‘It’s not all right,’ she repeated. ‘She isn’t coming.’

Beth took the envelope that the old lady was still clasping and extracted a single sheet of paper. With growing anger, she read: The journey has been difficult but I’ve arrived in London at last. I will try and get to you soon. You know that is what I want above all else. But I’m feeling so tired that I’m not sure now I can make it as far as Sussex. I will write again when I feel better.

Someone was playing tricks, Beth was sure. It was cruel beyond belief. The letters were typewritten and never signed, but Mrs Summer had become convinced they came from a daughter who had disappeared thirty years ago. Why the old lady believed this, Bethany wasn’t sure. It was perhaps a simple longing for it to be true. Elizabeth Summer, she’d learnt, had never contacted her family since the day she’d eloped to marry a man of whom they disapproved. Could a much loved daughter be so callous as never to have written? Beth thought not. After all these years of silence, it was most likely that the woman was dead.

When Beth had first met her employer, it seemed that Alice Summer had thought so, too. But then the letters had started to arrive – as far as Beth knew, none had come earlier – and the old lady had become convinced that Elizabeth was still in the world. It was pointless to argue away her belief. In some corner of her mind she must always have kept her daughter alive. Hadn’t May Prendergast said that despite her long standing opposition, Mrs Summer had eventually agreed to employ a companion on the basis of a single name? Bethany, Beth, Elizabeth. The letters must have ignited a long suppressed desire and given it heart. Beth hadn’t told May about the letters, and Mr Ripley and Molly Dumbrell knew only to intercept them. The fewer people who knew of Alice’s fantasy, the better.

She took the sheet of paper and folded it back into the envelope. She would destroy it, as she had with the others, and hope Mrs Summer might forget she had ever received it. She stayed kneeling by her side, continuing to cuddle the meagre frame until she felt Alice relax a little. ‘Shall I put the kettle on?’ she said brightly. ‘We can talk over tea – I’ve some news for you from the village.’

She’d hoped this might spark interest, but the elderly woman continued to stare into her lap.

‘I met May,’ she pursued.

‘May Lacey?’ Alice lifted her head.

‘Her mother sends you her very best wishes. She’d love to come and see you, but May says that she’s almost bed-bound now.’ Mrs Lacey had once been the housekeeper at Summerhayes.

‘She was a good worker,’ Alice mused, the past as always having the power to animate. ‘A trifle sharp at times, but a good worker. And her daughter – she was a bonny girl. She did well for herself, she married the curate – May Prendergast she became – and then she got to be the vicar’s wife. Fancy that. It was a shame he died. It’s not a happy thing being a widow and this new man at the church – tsk. I’d not give him the time of day. He is far too opinionated, far too sure of himself.’

That was probably what a vicar should be, Beth reflected, but the thought remained unspoken; it was clear that Alice liked her religion vague. ‘Mrs Lacey may not be able to visit, but May will come.’ She paused at the sitting room door. ‘She’s promised to call in later this week. She has some new children to settle in the village first. They’re evacuees from Brighton – apparently the house they’ve been staying in has been declared unsafe.’

She looked forward, as much as her employer, to May’s visits. Despite their age difference, the two of them had become good friends in the few months she had been at Summerhayes. It had been May who had placed the advertisement in The Lady.

We had the devil’s own job to persuade her to get help, May had said. Me and Mr Ripley between us. She doesn’t like change and the thought of someone new in the house sent her frantic. But then she saw your letter – you’d signed it Beth – and that was enough.

Beth never used her full name if she could possibly help it. Bethany had been her father’s choice, but it served to remind her always of an old shame and of her difference from the new family her mother had created. In this case though, it had worked to her advantage. A letter signed Beth had won her the job, that and the fact that she was not much older than Elizabeth Summer had been when she had disappeared. Alice must have been thinking of Elizabeth long before the letters arrived. Letters and long lost daughters, it was an alchemy, but it had given her employment when she was desperate for work and desperate to avoid a forced retreat to the home she hated and the family who didn’t want her.

‘Will Ivy come with her?’ Alice asked. ‘When May visits?’

‘Ivy is married now, remember? That’s why May advertised in the magazine. That’s why I’m here.’

‘I remember. Of course I remember. Dear Ivy. Such a stalwart girl. And she was Elizabeth’s maid before she was mine.’

‘I know, Mrs Summer.’ Alice must have told her a dozen times already. It was as though the missing girl had come to dominate her mind to the exclusion of all else.

‘Yes,’ the old lady was saying, ‘she and Elizabeth were maid and mistress, but that didn’t matter. They grew up together and were the best of friends. Ivy knew all Elizabeth’s secrets.’ Alice turned to look out of the window. The scene below was one of frenetic activity, but it was clear that she saw none of it. ‘All her secrets,’ she repeated, ‘except where she’d gone. Elizabeth never told her that. She didn’t want to get the girl into trouble.’

The old face drooped and a tear formed in the corner of her eye. She looked hopelessly around, then caught sight of the letter still in Beth’s grasp. With difficulty she wriggled to the edge of her seat, tensing her feet on the floor, as though she would launch herself forward. Then, with both hands, reached out for the oblong of white paper.

‘I’ll put it on the mantelpiece for now and make the tea,’ Beth said hastily.

Chapter Three (#ulink_7d2bc650-8f9d-5b06-a00a-fa22aecbdc13)

The kitchen was looking bright and clean. At least Molly knew her job even if she couldn’t remember instructions. They rarely drank tea before evening and Beth hoped there would be enough to last them the next seven days. Standing in the grocer’s this morning, it seemed as though the number of coupons in their ration books shrank by the week. She put the kettle to boil and found two clean cups. It was then she became aware that the kitchen table was smothered in flowers: a wonderful bouquet of yellow freesias and white lilies. Molly must have taken delivery of them before she left. There was a card attached and she bent to read. To dear Aunt Alice. I hope these cheer you. Gilbert.

Such a kind thought. Gilbert Fitzroy had left on business but despite all the rush and bother of departure, he hadn’t forgotten his aunt. She hoped Alice would say thank you when he returned, though she couldn’t depend on it. Gilbert might be a devoted nephew but his aunt was slow in returning his regard. Whenever he called, it seemed that Alice was too tired to see him, or she was listening to her favourite wireless programme and didn’t want to be disturbed, or it was time for lunch or tea or supper. Beth had so far been unable to discover what the problem might be. No doubt the root of the trouble lay in the past since this was where Alice dwelt for most of her waking hours. Gilbert appeared unfazed by his aunt’s evident lack of affection and continued to enquire of her health and, from time to time, sent small gifts from the Amberley estate, including today’s magnificent flowers filling the small kitchen with their perfume. She would have noticed them earlier if her nerves had not been so jangled. She must thank Gilbert as soon as he got back, even if his aunt did not. In the meantime, she would do her best to return the favour by teaching his son as much as Ralph was willing to learn. So far, that hadn’t proved a great deal; Ralph was not an academic child.

She went back into the sitting room and handed Alice her cup of tea, making sure the old lady had a firm hold of the saucer. Then she returned to the kitchen and gathered up the bouquet. ‘Look, you have flowers, Mrs Summer. Aren’t they splendid? I hope I can find a vase that’s big enough. Perhaps the Venetian one?’ That was Alice’s favourite.

The old lady’s face brightened. She loved flowers, loved colour. ‘I always had fresh flowers, every few days. Mr Harris – he was the Head Gardener – he’d cut me new blooms and they would fill the house.’

‘They must have looked lovely – and smelt lovely, too.’