Полная версия:

The Piratical Miss Ravenhurst

Join favourite author

Louise Allen

as she explores the tangled love-lives of

Those Scandalous Ravenhursts

First, you travelled across

war-torn Europe with

THE DANGEROUS MR RYDER

Then you accompanied Mr Ryder’s sister,

THE OUTRAGEOUS LADY FELSHAM, on her quest for a hero.

You were scandalised by

THE SHOCKING LORD STANDON

You shared dangerous, sensual adventures

with

THE DISGRACEFUL MR RAVENHURST

You were seduced and swept off your feet by

THE NOTORIOUS MR HURST

Now meet

THE PIRATICAL MISS RAVENHURST

Author Note

After five Ravenhurst love stories it is time to meet the youngest and most distant of the cousins. Clemence lives a life of privilege and comfort at the heart of Jamaican society until circumstances force her to make a choice—marriage to the despicable Lewis Naismith or flight.

Clemence has a plan—Ravenhursts always do—but it does not include running straight into the clutches of the most feared pirate in the Caribbean. There doesn’t seem any way out, unless she can trust both her instincts and the enigmatic navigator Nathan Stanier.

I knew Clemence would have the courage and wits to survive on the Sea Scorpion, but what is a young lady to do when she is comprehensively ruined in the process?

I do hope you enjoy finding out as much as I did. I felt sad to write the last word in the chronicles of Those Scandalous Ravenhursts, but perhaps one day I can return to their world and explore the life and loves of some of the other characters I met along the way.

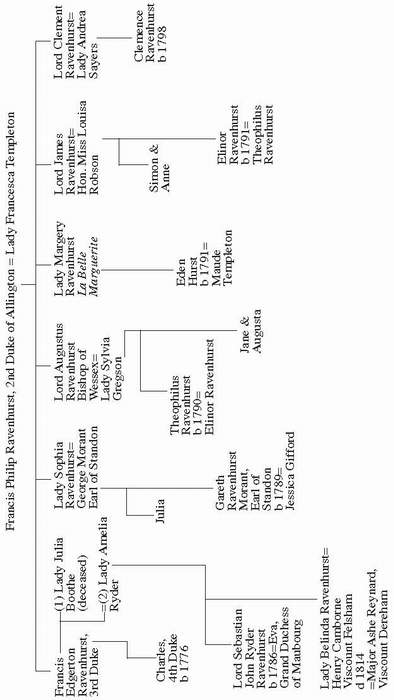

RAVENHURST FAMILY TREE

Louise Allen has been immersing herself in history, real and fictional, for as long as she can remember, and finds landscapes and places evoke powerful images of the past. Louise divides her time between Bedfordshire and the Norfolk coast, where she spends as much time as possible with her husband at the cottage they are renovating. With any excuse she’ll take a research trip abroad—Venice, Burgundy and the Greek islands are favourite atmospheric destinations. Please visit Louise’s website—www.louiseallenregency.co.uk—for the latest news!

Recent novels by the same author:

THE BRIDE’S SEDUCTION

NOT QUITE A LADY

A MOST UNCONVENTIONAL COURTSHIP

NO PLACE FOR A LADY

DESERT RAKE

(in Hot Desert Nights)

VIRGIN SLAVE, BARBARIAN KING

THE DANGEROUS MR RYDER*

THE OUTRAGEOUS LADY FELSHAM*

THE SHOCKING LORD STANDON*

THE DISGRACEFUL MR RAVENHURST*

THE NOTORIOUS MR HURST*

*Those Scandalous Ravenhursts

THE PIRATICAL MISS RAVENHURST

Louise Allen

www.millsandboon.co.uk

For Nathan Oakman

who is sure to grow up to be a hero

Chapter One

Jamaica—June 1817

‘I would sooner—’

‘Sooner what?’ Her uncle regarded Clemence with contempt. ‘You would sooner die?’

‘Sooner marry the first man I met outside the gates than that.’ She jerked her head towards her cousin, sprawled in the window seat, his attention on the female servants in the torch-lit courtyard below.

‘But you do not have any choice,’ Joshua Naismith said, in the same implacably patient tone he had used to her in the six months since her father’s death. ‘You are my ward, you will do as I tell you.’

‘My father never intended me to marry Lewis,’ Clemence protested. She had been protesting with a rising sense of desperation ever since she had recovered sufficiently from her daze of mourning to comprehend that her late mother’s half-brother was not the protector that her father had expected him to be when he made his will. Her respectable, conservative, rather dull Uncle Joshua was a predator, his claws reaching for her fortune.

‘The intentions of the late lamented Lord Clement Ravenhurst,’ Mr Naismith said, ‘are of no interest to me whatsoever. The effect of his will is to place you under my control, a fitting recompense for years of listening to his idiotic political opinions and his absurd social theories.’

‘My father did not believe in the institution of slavery,’ Clemence retorted, angered despite her own apprehension. ‘Most enlightened people feel the same. You did not have to listen to what you do not believe in—you could have attempted to counter his arguments. But then you have neither the intellectual capacity, nor the moral integrity to do so, have you, Uncle?’

‘Insolent little bitch.’ Lewis uncoiled himself from the seat and walked to his father’s side. He frowned at her, an expression she had caught him practising in front of the mirror, no doubt in an attempt to transform his rather ordinary features into an ideal of well-bred authority. ‘A pity you were not a boy—he raised you like one, he let you run wild like one and now, look at you—you might as well be one.’

Clemence hated the flush she could feel on her cheekbones, hated the fact that his words stung. It was shallow to wish she had a petite, curvaceous figure. A few months ago she had at least possessed a small bosom and the gentle swell of feminine hips, now, with the appetite of a mouse, she had lost so much weight that she might as well have been twelve again. Combined with the rangy height she had inherited from her father, Clemence was all too aware that she looked like a schoolboy dressed up to play a female role in a Shakespeare play.

Defensively her hand went to the weight of her hair, coiled and dressed simply in the heat. Its silky touch reminded her of her femininity, her one true beauty, all the colours of wheat and toffee and gilt, mixed and mingling.

‘If I had been a boy, I wouldn’t have to listen to your disgusting marriage plans,’ she retorted. ‘But you’d still be stealing my inheritance, whatever my sex, I have no doubt of that. Is money the only thing that is important to you?’

‘We are merchants.’ Uncle Joshua’s high colour wattled his smooth jowls. ‘We make money, we do not have it drop into our laps like your aristocratic relatives.’

‘Papa was the youngest son, he worked for his fortune—’

‘The youngest son of the Duke of Allington. Oh dear, what poverty, how he must have struggled.’

That was the one card she had not played in the weeks as hints had become suggestions and the suggestions, orders. ‘You know my English relatives are powerful,’ Clemence said. ‘Do you wish to antagonise them?’

‘They are a very long way away and hold no sway here in the West Indies.’ Joshua’s expression was smug. ‘Here the ear of the Governor and one’s credit with the bankers are all that matter. In time, when Lewis decides to go back to England, his marriage to you may well be of social advantage, that is true.’

‘As I have no intention of marrying my cousin, he will have no advantage from me.’

‘You will marry me.’ Lewis took a long stride, seized her wrist and yanked her, off-balance, to face him. She was tall enough to stare into his eyes, refusing to flinch even as his fingers dug into the narrow bones of her wrist, although her heart seemed to bang against her ribs. ‘The banns will be read for the first time next Sunday.’

‘I will never consent and you cannot force me kicking and screaming to the altar—not and maintain your precious respectability.’ Somehow she kept her voice steady. It was hard after nineteen years of being loved and indulged to find the strength to fight betrayal and greed, but some unexpected reserve of pride and desperation was keeping her defiant.

‘True.’ Her head snapped round at the smugness in her uncle’s voice. Joshua smiled, confident. The chilly certainty crept over her that he had thought long and hard about this and the thought of her refusal on the altar steps did not worry him in the slightest. ‘You have two choices, my dear niece. You can behave in a dutiful manner and marry Lewis when the banns have been called or he will come to your room every night until he has you with child and then, I think, you will agree.’

‘And if I do not, even then?’ Fainting, Clemence told herself fiercely, would not help in the slightest, even though the room swam and the temptation to just let go and slip out of this nightmare was almost overwhelming.

‘There is always a market for healthy children on the islands,’ Lewis said, hitching one buttock on the table edge and smiling at her. ‘We will just keep going until you come to your senses.’

‘You—’ Clemence swallowed and tried again. ‘You would sell your own child into slavery?’

Lewis shrugged. ‘What use is an illegitimate brat? Marry me and your children will want for nothing. Refuse and what happens to them will be entirely your doing.’

‘They will want for nothing save a decent father,’ she snapped back, praying that her churning stomach would not betray her. ‘You are a rapist, an embezzler and a blackmailer and you—’ she turned furiously on her uncle ‘—are as bad. I cannot believe your lackwit son thought of this scheme all by himself.’

Joshua had never hit her before, no one had. Clemence did not believe the threat in her uncle’s raised hand, did not flinch away until the blow caught her on the cheekbone under her right eye, spinning her off her feet to crash against the table and fall to the floor.

Somehow she managed to push herself up, then stumble to her feet, her head spinning. Joshua Naismith’s voice came from a long way away, his image so shrunk he seemed to be at the wrong end of a telescope. His voice buzzed in her ears. ‘Will you consent to the banns being read and agree to marry Lewis?’

‘No.’ Never.

‘Then you will go to your room and stay there. Your meals will be brought to you and you will eat; your scrawny figure offends me. Lewis will visit you tomorrow. I think you are in no fit state to pay him proper heed tonight.’

Proper heed? If her cousin came within range of her and any kind of sharp weapon he would never be able to father a child again. ‘Ring for Eliza,’ Clemence said, lifting her hand to her throbbing face. ‘I need her assistance.’

‘You have a new abigail.’ Joshua reached out and tugged the bell. ‘That insolent girl of yours has been dismissed. Freed slaves indeed!’ The woman who entered was buxom, her skin the colour of smooth coffee, her hair braided intricately. The look she shot Clemence held contempt and dislike.

‘Your mistress?’ She stared at Lewis. No wonder Marie Luce was looking like that: she must know the men’s intentions and know that Clemence would be taking Lewis’s attention away from her.

‘She does as she is told,’ Lewis said smoothly. ‘And will be rewarded for it. Take her to her chamber, make sure she eats,’ he added to the other woman. ‘Lock the door and then come to my room.’

Clemence let herself be led out of the door. Here, in the long passage with its louvred windows open at each end to encourage a draught, the sound of the sea on the beach far below was a living presence. Her feet stumbled on the familiar smooth stone flags. From the white walls the darkened portraits of generations of ancestors stared blankly down, impotent to help her.

‘Where is Eliza?’ Thank goodness her maid was a freed woman with her own papers, not subject to the whim of the Naismiths.

Marie Luce shrugged, her dark eyes hostile as she gripped Clemence’s arm, half-supporting, half-imprisoning her. ‘I do not know. I do not care.’ Her lilting accent made poetry out of the acid words. ‘Why do you make Master Lewis angry? Marry him, then he will get you with child and forget about you.’

‘I do not want him, you are welcome to him,’ Clemence retorted as they reached the door of her room. ‘Please fetch me some warm water to bathe my face.’ The door clicked shut behind the maid and the key turned. Through the slats she could hear her heelless shoes clicking as she made her way to the back door and the kitchen wing.

Clemence sank down on the dressing-table stool, her fingers tight on the edge for support. The image that stared back at her from the mirror was not reassuring. Her right cheek was already swelling, the skin red and darkening, her eye beginning to close. It would be black tomorrow, she realised. Her left eye, wide, looked more startlingly green in contrast and her hair had slipped from its pins and lay in a heavy braid on her shoulder.

Gingerly, Clemence straightened her back, wincing at the bruises from the impact with the table. There was no padding on her bones to cushion any falls, she realised; it was mere luck she had not broken ribs. She must eat. Starving herself into a decline would not help matters, although what would?

The door opened to admit Marie Luce with one of the footmen carrying a supper tray. The man, one of the house staff she had known all her life, took a startled look at her face and then stared straight ahead, expressionless. ‘Master Lewis says you are to eat,’ the other woman said, putting down the water ewer she held. ‘I stay until you do.’

Clemence dipped a cloth in the water and held it to her face. It stung and throbbed: she supposed she should be grateful Uncle Joshua had used his ringless right hand and the blow had not broken the skin. ‘Very well.’ Chicken and rice, stuffed pimentos, corn fritters, cake with syrup, milk. Her stomach roiled, but instinct told Clemence to eat, however little appetite she had and however painful it was to chew.

She knew the worst now: it was time to fight, although how, locked in her room, she had no idea. The plates scraped clean and the milk drunk, Marie Luce cleared the table and let herself out. Clemence strained to hear—the key grated in the lock. It was too much to hope that the woman would be careless about that.

She felt steadier for the food. It seemed weeks since she had eaten properly, grief turning to uneasiness, then apprehension, then fear as her uncle’s domination over the household and estate and her life had tightened into a stranglehold.

It was pointless to expect help from outside; their friends and acquaintances had been told she was ill with grief, unbalanced, and the doctor had ordered complete seclusion and rest. Even her close friends Catherine Page and Laura Steeples had believed her uncle’s lies and obediently kept away. She had seen their letters to him, full of shocked sympathy that she was in such a decline.

And who could she trust, in any case? She had trusted Joshua, and how wrong she had been about him!

Clemence stood and went to the full-length window, its casement open on to the fragrant heat of the night. Her father had insisted that Raven’s Hold was built right on the edge of the cliff, just as the family castle in Northumberland was, and the balcony of her room jutted out into space above the sea.

When she was a child, after her mother’s death, she had run wild with the sons of the local planters, borrowing their clothes, scrambling through the cane fields, hiding in the plantation buildings. Scandalised local matrons had finally persuaded her father that she should become a conformable young lady once her fourteenth birthday was past and so her days of climbing out of the window at night and up the trellis to freedom and adventures were long past.

She leaned on the balcony and smiled, her expression turning into a grimace as the bruises made themselves felt. If only it were so easy to climb away now!

But why not? Clemence straightened, tinglingly alert. If she could get out of the house, down to the harbour, then the Raven Princess would be there, due to sail for England with the morning light. It was the largest of her father’s ships—her ships—now that pirates had captured Raven Duchess, the action that had precipitated her father’s heart stroke and death.

But if she just ran away they would hunt her down like a fugitive slave…Clemence paced into the room, thinking furiously. Her uncle’s sneer came back to her. You would sooner die? Let him think that, then. Somewhere, surely, were the boy’s clothes she had once worn. She pulled open presses, flung up the lids of the trunks, releasing wafts of sandalwood from their interiors. Yes, here at the bottom of one full of rarely used blankets were the loose canvas breeches, the shirt and waistcoat.

She pulled off her gown and tried them on. The bottom of the trousers flapped above her ankle bones now, but the shirt and waistcoat had always been on the large side. After some thought she tore linen strips and bound her chest tightly; her bosom was unimpressive, but even so, it was better to take no chances. Clemence dug out the buckled shoes, tried them on her bare feet, then looked in the mirror. The image of a gangly youth stared back, oddly adorned by the thick braid of hair.

That was going to have to go, there was no room for regret. Clemence found the scissors, gritted her teeth and hacked. The hair went into a cloth, knotted tightly, then wrapped up into a bundle with everything she had been wearing that evening. A thought struck her and she took out the gown again to tear a thin, ragged strip from the hem. Her slippers she flung out of the window and the modest pearls and earrings she buried under the jewellery in her trinket box.

The new figure that looked back at her from the glass had ragged hair around its ears and a dramatically darkening bruise over cheek and eye. Her mind seemed to be running clearly now, as though she had pushed through a forest of fear and desperation into open air. Clemence took the pen from the standish and scrawled I cannot bear it… On a sheet of paper. A drop of water from the washstand was an artistic and convincing teardrop to blur the shaky signature. The ink splashed on to the dressing table, over her fingers. All the better to show agitation.

She looped the bundle on to her belt and set a stool by the balcony before scrambling up on to the rail. Perched there, she snagged the strip from her gown under a splinter, then kicked the stool over. There: the perfect picture of a desperate fall to the crashing waves below. How Uncle Joshua was going to explain that was his problem.

Now all she had to do was to ignore the lethal drop below and pray that the vines and the trellis would still hold her. Clemence reached up, set her shoe on the first, distantly remembered foothold, and swung clear of the rail.

She rapidly realised just how dangerous this was, something the child that she had been had simply not considered. And five years of ladylike behaviour, culminating in weeks spent almost ill with grief and desperation, had weakened her muscles. Her dinner lurched in her stomach and her throat went dry. Teeth gritted she climbed on, trying not to think about centipedes, spiders or any of the other interesting inhabitants of the ornamental vines she was clutching. However venomous they might be, they were not threatening to rape and rob her.

The breath sobbed in her throat, but she reached the ledge that ran around the house just beneath the eaves and began to shuffle along it, clinging to the gutters. All she had to do now was to get around the corner and she could drop on to the roof of the kitchen wing. From there it was an easy slide to the ground.

A shutter banged open just below where her heels jutted out into space. Clemence froze. ‘No, I don’t want her, how many times have I got to tell you?’ It was Lewis, irritated and abrupt. ‘Why would I want that scrawny, cantankerous little bitch? It is simply business.’

There was the sound of a woman’s voice, low and seductive. Marie Luce. Lewis grunted. ‘Get your clothes off, then.’ Such a gallant lover, Clemence thought. Her cousin had left the shutters open, forcing her to move with exaggerated care in case her leather soles gritted on the rough stone. Then she was round, dropping on to the thick palmetto thatch, sliding down to the leanto shed roof and clambering to the ground.

Old One-Eye, the guard dog, whined and came over stiffly to lick her hand, the links of his chain chinking. There was noise from the kitchens, the hum and chirp of insects, the chatter of a night bird. No one would hear her stealthy exit through the yard gate, despite the creaky hinge that never got oiled.

Clemence took to her heels, the bundle bouncing on her hip. Now all she had to do was to get far enough away to hide the evidence that she was still alive, and steal a horse.

It was a moonless night, the darkness of Kingston harbour thickly sprinkled with the sparks of ships’ riding-lights. Clemence slid from the horse’s back, slapped it on the rump and watched it gallop away, back towards the penn she had taken it from almost three hours before.

The unpaved streets were rough under her stumbling feet but she pushed on, keeping to the shadows, avoiding the clustered drinking houses and brothels that lined the way down to the harbour. It was just her luck that Raven Princess was moored at the furthest end, Clemence thought, dodging behind some stacked barrels to avoid a group of men approaching down the centre of the street.

And when she got there, she was not at all certain that simply marching on board and demanding to be taken to England was a sensible thing to do. Captain Moorcroft could well decide to return her to Uncle Joshua, despite the fact that the ship was hers. The rights of women was not a highly regarded principle, let alone here on Jamaica in the year 1817.

The hot air held the rich mingled odours of refuse and dense vegetation, open drains, rum, wood smoke and horse dung, but Clemence ignored the familiar stench, quickening her pace into a jog trot. The next quay was the Ravenhurst moorings and the Raven Princess…was gone.

She stood staring, mouth open in shock, mind blank, frantically scanning the moored ships for a sight of the black-haired, golden-crowned figurehead. It must be here!

‘What you looking for, boy?’ a voice asked from behind her.

‘The Raven Princess,’ she stammered, her voice husky with shock and disbelief.

‘Sailed this evening, damn them, they finished loading early. What do you want with it?’

Clemence turned, keeping her head down so the roughly chopped hair hid her face. ‘Cabin boy,’ she muttered. ‘Cap’n Moorcroft promised me a berth.’ There were five men, hard to see against the flare of light from a big tavern, its doors wide open on to the street.

‘Is that so? We could do with a cabin boy, couldn’t we, lads?’ the slightly built figure in the centre of the group said, his voice soft. The hairs on Clemence’s nape rose. The others sniggered. ‘You come along with us, lad. We’ll find you a berth all right.’

‘No. No, thank you.’ She began to edge away.

‘That’s “No, thank you, Cap’n”,’ a tall man with a tricorne hat on his head said, stepping round to block her retreat.

‘Cap’n,’ she repeated obediently. ‘I’ll just—’

‘Come with us.’ The tall man gave her a shove, right up to the rest of the group. The man he called Cap’n put out a hand and laid it on her shoulder. She was close enough to see him now, narrow-faced, his bony jaw obscured by a few days’ stubble, his head bare. His clothes were flamboyant, antique almost; coat tails wide, the magnificent lace at his throat, soiled. The eyes that met Clemence’s were brown, flat, cold. If a lizard could speak…