Полная версия:

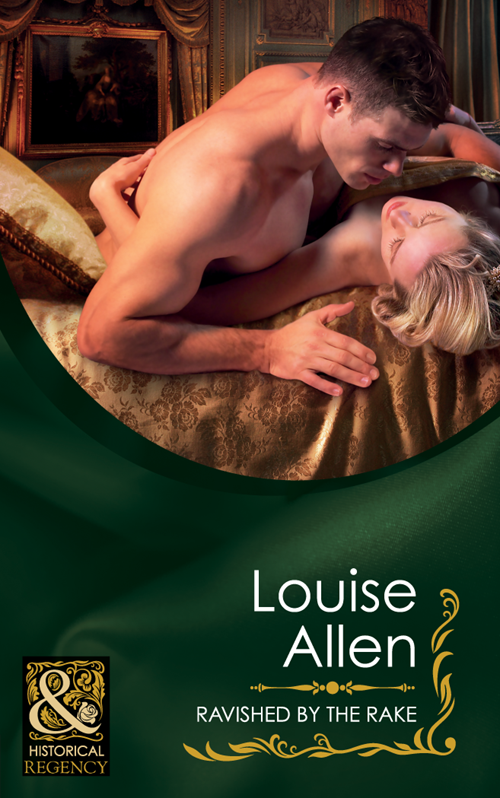

Ravished by the Rake

Introducing Louise Allen’s most scandalous trilogy yet!

DANGER & DESIRE

Leaving the sultry shores of India behind them, the passengers of the Bengal Queen face a new life ahead in England—until a shipwreck throws their plans into disarray …

Can Alistair and Perdita’s illicit onboard flirtation survive the glittering social whirl of London?

Washed up on an island populated by ruffians, virginal Averil must rely on rebel captain Luc for protection …

And honourable Callum finds himself falling for his brother’s fiancée!

Look for

RAVISHED BY THE RAKE August 2011

SEDUCED BY THE SCOUNDREL September 2011

MARRIED TO A STRANGER October 2011

from Mills & Boon® Historical

Alistair caught her as she stumbled back. ‘The door must have been unlocked,’ he said as she stared about her, confused. ‘It’s an empty cabin.’ There was just enough light to see. Alistair reached outside, lifted a lamp from the wall and came in, closing the door behind him. She heard the click of the key as he stood there.

‘Alistair—’

‘Yes?’ he said, putting down the lantern and coming to pull her into his arms. ‘What do you want, Dita?’

‘I don’t know.’ She tugged at his waistcoat buttons. ‘You.’

‘I want you, too,’ he said as she undid the last of them and began to pull his shirt from his waistband. ‘I only meant to kiss you: I should have known it wouldn’t stop there. Trust me a little more, Dita? Trust me to pleasure you?’

‘Yes,’ she said, not quite understanding what he was asking, what it meant. ‘I need to touch you …’

About the Author

LOUISE ALLEN has been immersing herself in history, real and fictional, for as long as she can remember, and finds landscapes and places evoke powerful images of the past. Louise lives in Bedfordshire, and works as a property manager, but spends as much time as possible with her husband at the cottage they are renovating on the north Norfolk coast, or travelling abroad. Venice, Burgundy and the Greek islands are favourite atmospheric destinations. Please visit Louise’s website—www.louiseallenregency.co.uk—for the latest news!

Novels by the same author:

VIRGIN SLAVE, BARBARIAN KING

THE DANGEROUS MR RYDER*

THE OUTRAGEOUS LADY FELSHAM*

THE SHOCKING LORD STANDON*

THE DISGRACEFUL MR RAVENHURST*

THE NOTORIOUS MR HURST*

THE PIRATICAL MISS RAVENHURST*

PRACTICAL WIDOW TO PASSIONATE MISTRESS†

VICAR’S DAUGHTER TO VISCOUNT’S LADY†

INNOCENT COURTESAN TO ADVENTURER’S BRIDE†

and in Mills & Boon® Historical Undone! eBooks: DISROBED AND DISHONOURED

* Those Scandalous Ravenhursts

† The Transformation of the Shelley Sisters

Ravished

by the Rake

Louise Allen

www.millsandboon.co.uk

Dedication

For the Regency Silk & Scandal ‘continuistas’

Author Note

Flying to India on holiday last year, I grew weary of the long flight, but I cheered up when I thought of how many months the passengers on the East India Company’s ships plying to and from the Far East must have been at sea together. Intrigued, I read more—especially the memoirs of the rake William Hickey, who spent much of his legal career in India and who described in vivid detail life on-board ship.

The voyage had its dangers, as well as its discomforts, and shipwrecks were not uncommon. I began to wonder what would happen to the passengers who survived such a disaster: would the bonds forged during months together withstand such a trauma? How would the wreck affect friends and lovers ashore?

This book is the first in a trio of novels that explores that question. Shocking Lady Perdita Brooke and rakish adventurer Alistair Lyndon strike sparks off each other from the moment they meet—but what will happen when the Bengal Queen is wrecked on the treacherous rocks of the Isles of Scilly?

I hope you enjoy finding out as much as I did, and will follow their fellow passengers in the next two books as three love stories emerge from the shipwreck.

Chapter One

7th December 1808—Calcutta, India

It was blissfully cool, Dita assured herself, plying her fan in an effort to make it so. This was the cool season, so at eight o’clock in the evening it was only as hot as an English August day. Nor was it raining, thank heavens. How long did one have to live in India to become used to the heat? A trickle of sweat ran down her spine as she reminded herself of what it had been like from March to September.

But there was something to be said for the temperature: it made one feel so delightfully loose and relaxed. In fact, it was impossible to be anything but relaxed, to shed as many clothes as decency permitted and wear exquisitely fine muslins and lawns and floating silks.

She was going to miss that cat-like, sensual, indolence when she returned to England, now her year of exile was over. And the heat had another benefit, she thought, watching the group of young ladies in the reception room off the great Marble Hall of Government House: it made the beautiful peaches-and-cream blondes turn red and blotchy whereas she, the gypsy, as they snidely remarked, showed little outward sign of it.

It had not taken long to adapt, to rise before dawn to ride in the cool, to sleep and lounge through the long, hot afternoons, saving the evenings for parties and dances. If it had not been for the grubby trail of rumour and gossip following her, she could have reinvented herself, perhaps, here in India. As it was, it had just added a sharper edge to her tongue.

But she wanted so much now to be in England. She wanted the green and the soft rain and the mists and a gentler sun. Her sentence was almost done: she could go home and hope to find herself forgiven by Papa, hope that her reappearance in society would not stir up the wagging tongues all over again.

And if it does? she thought, strolling into the room from the terrace, her face schooled to smiling confidence. Then to hell with them, the catty ones with their whispers and the rakes who think I am theirs for the asking. I made a mistake and trusted a man, that is all. I will not do that again. Regrets were a waste of time. Dita slammed the door on her thoughts and scanned the room with its towering ceiling and double rows of marble columns.

The Bengal Queen was due to sail for England at the end of the week and almost all her passengers were here at the Governor’s House reception. She was going to get to know them very well indeed over the next few months. There were some important men in the East India Company travelling as supercargo; a handful of army officers; several merchants, some with wives and daughters, and a number of the well-bred young men who worked for the Company, setting their feet on the ladder of wealth and power.

Dita smiled and flirted her fan at two of them, the Chatterton twins on the far side of the room. Lazy, charming Daniel and driven, intense Callum—Mama would not be too displeased if she returned home engaged to Callum, the unattached one. Not a brilliant match, but they were younger brothers of the Earl of Flamborough, after all. Both were amusing company, but neither stirred more than a flutter in her heart. Perhaps no one would ever again, now she had learned to distrust what it told her.

Shy Averil Heydon waved from beside a group of chaperons. Dita smiled back a trifle wryly. Dear Averil: so well behaved, such a perfect young lady—and so pretty. How was it that Miss Heydon was one of the few eligible misses in Calcutta society whom she could tolerate? Possibly because she was such an heiress that she was above feeling delight at an earl’s daughter being packed off the India in disgrace, unlike those who saw Lady Perdita Brooke as nothing but competition to be shot down. The smile hardened; they could certainly try. None of them had succeeded yet, possibly because they made the mistake of thinking that she cared for their approval or their friendship.

And Averil would be on the Bengal Queen, too, which was something to be grateful for—three months was a long time to be cooped up with the same restricted company. On the way out she’d had her anger—mostly directed at herself—and a trunk full of books to sustain her; now she intended to enjoy herself, and the experience of the voyage.

‘Lady Perdita!’

‘Lady Grimshaw?’ Dita produced an attentive expression. The old gorgon was going to be a passenger, too, and Dita had learned to pick her battles.

‘That is hardly a suitable colour for an unmarried girl. And such flimsy fabric, too.’

‘It is a sari I had remade, Lady Grimshaw. I find pastels and white make me appear sallow.’ Dita was well aware of her few good features and how to enhance them to perfection: the deep green brought out the colour of her eyes and the dark gold highlights in her brown hair. The delicate silk floated over the fine lawn undergarments as though she was wearing clouds.

‘Humph. And what’s this I hear about riding on the maidan at dawn? Galloping!’

‘It is too hot to gallop at any other time of day, ma’am. And I did have my syce with me.’

‘A groom is neither here nor there, my girl. It is fast behaviour. Very fast.’

‘Surely speed is the purpose of the gallop?’ Dita said sweetly, and drifted away before the matron could think of a suitably crushing retort. She gestured to a servant for a glass of punch, another fast thing for a young lady to be doing. She sipped it as she walked, wrinkling her nose at the amount of arrack it contained, then stopped as a slight stir around the doorway heralded a new arrival.

‘Who is that?’ Averil appeared at her side and gestured towards the door. ‘My goodness, what a very good-looking man.’ She fanned herself as she stared.

He was certainly that. Tall, lean, very tanned, the thick black silk of his hair cut ruthlessly short. Dita stopped breathing, then sucked down air. No, of course not, it could not be Alistair—she was imagining things. Her treacherous body registered alarm and an instant flutter of arousal.

The man entered limping, impatient, as though the handicap infuriated him, but he was going to ignore it. Once in, he surveyed the room with unhurried assurance. The scrutiny paused at Dita, flickered over her face, dropped to study the low-cut neckline of her gown, then moved on to Averil for a further cool assessment.

For all the world like a pasha inspecting a new intake for the seraglio, Dita thought. But despite the unfamiliar arrogance, she knew. Her body recognised him with every quivering nerve. It is him. It is Alistair. After eight years. Dita fought a battle with the urge to run.

‘Insufferable,’ Averil murmured. She had blushed a painful red.

‘Insufferable, no doubt. Arrogant, certainly,’ Dita replied, not troubling to lower her voice as he came closer. Attack, her instincts told her. Strike before you weaken and he can hurt you again. ‘And he obviously fancies himself quite the romantic hero, my dear. You note the limp? Positively Gothic—straight out of a sensation novel.’

Alistair stopped and turned. He made no pretence of not having heard her. ‘A young lady who addles her brain with trashy fiction, I gather.’ The intervening years had not darkened the curious amber eyes that as a child she had always believed belonged to a tiger. Memories surfaced, some bittersweet, some simply bitter, some so shamefully arousing that she felt quite dizzy. She felt her chin go up as she returned the stare in frigid silence, but he had not recognised her. He turned a little more and bowed to Averil. ‘My pardon, ma’am, if I put you to the blush. One does not often see such beauty.’

The movement exposed the right side of his head. Down the cheek from just in front of the ear, across the jawbone and on to his neck, there was a half-healed scar that vanished into the white lawn of his neckcloth. His right hand, she saw, was bandaged. The limp was not affectation after all; he had been hurt, and badly. Dita stifled the instinct to touch him, demand to know what had happened as she once would have done, without inhibition.

Beside her she heard her friend’s sharp indrawn breath. ‘I do not regard it, sir.’ Averil nodded with cool dismissal and walked away towards the chaperons, then turned when she reached their sanctuary, her face comically dismayed as she realised Dita had not followed her.

I should apologise to him, Dita thought, but he ogled us so blatantly. And he cut at me just as he had that last time. Furthermore, he apologised only to Averil; her own looks would win no compliments from this man.

‘My friend is as gracious as she is beautiful,’ she said and the amber eyes, still warm from following Averil’s retreat, moved back to hers. He frowned at the tart sweetness of her tone. ‘She can find it in herself to forgive almost anyone, even presumptuous rakes.’ Which is what Alistair appeared to have grown into.

And on that note she should turn on her heel, perhaps with a light trill of laughter, or a flick of her fan, and leave him to annoy some other lady. But it was difficult to move, when wrenching her eyes away from his meant they fell to his mouth. It did not curve—he could not be said to be smiling—but one corner deepened into something that was almost a dimple. Not, of course, that such an arrogant hunk of masculinity could be said to have anything as charming as a dimple. That mouth on her skin, on her breast …

‘I am rightly chastised,’ he said. There was something provocative in the way that he said it that sent a little shock through her, although she had no idea why. Then she realised that he was speaking to her as a woman, not as the girl he had thought her when he had so cruelly dismissed her before. It was almost as though he was suggesting that she carry out the chastisement more personally.

Dita told herself that one could overcome blushes by sheer force of will, especially as she had no very exact idea what she was blushing about now. He did not recognise her; even if he did, what had happened so long ago had been unimportant to him, he had made that very clear at the time. ‘You do not appear remotely penitent, sir,’ she retorted. Sooner or later he would realise who he was talking to, but she was not going to give him the satisfaction of acknowledging him and thinking she attached any importance to it.

‘I never said I was, ma’am, merely that I acknowledged a reproof. There is no amusement in penitence—why, one would have to either give up the sin or be a hypocrite—and where’s the fun in that?’

‘I have no idea whether you are a hypocrite or not, sir, but certainly no one could accuse you of gallant behaviour.’

‘You struck first,’ he pointed out, accurately and unfairly.

‘For which I apologise,’ Dita said. She was not going to act as badly as he. Even as she made the resolution her tongue got the better of her. ‘But I have no intention of offering sympathy, sir. You obviously enjoy fighting.’ He had always been intense, often angry, as a youth. And that intensity had miraculously transmuted into fire and passion when he made love.

‘Indeed.’ He flexed the bandaged hand and winced slightly. ‘You should see the other fellow.’

‘I have no wish to. You appear to have been hacking at each other with sabres.’

‘Near enough,’ he agreed.

Something in the mocking, cultured tones still held the faintest burr of the West Country. A wave of nostalgia for home and the green hills and the fierce cliffs and the cold sea gripped her, overriding even the shock of seeing Alistair again.

‘You still have the West Country in your voice,’ Dita said abruptly.

‘North Cornwall, near the boundary with Devon. And you?’ He did not appear to find the way she had phrased the statement strange.

He misses it, too, she thought, hearing the hint of longing under the cool tone. ‘I, too, come from that area.’ Without calculation she put out her hand and he caught it in his uninjured, ungloved, left. His hand was warm and hard with a rider’s calluses and his fingertips rested against her pulse, which was racing. Once before he had held her hand like this, once before they had stood so close and she had read the need in his eyes and she had misunderstood and acted with reckless innocence. He had taken her to heaven and then mocked her for her foolishness.

She could not play games any longer. Sooner or later he would find out who she was, and if she made a mystery of it he would think she still remembered, still attached some importance to what had happened between them. ‘My family lives at Combe.’

‘You are a Brooke? One of the Earl of Wycombe’s family?’ He moved nearer, her hand still held in his as he drew her to him to study her face. Close to he seemed to take the air out of the space between them. Too close, too male. Alistair. Oh my lord, he has grown up. ‘Why, you are never little Dita Brooke? But you were all angles and nose and legs.’ He grinned. ‘I used to put frogs in your pinafore pocket and you tagged along everywhere. But you have changed since I last saw you. You must have been twelve.’ His amusement stripped the eight years from him.

‘I was sixteen,’ she said with all the icy reserve she could manage. All angles and nose. ‘I recall you—and your frogs—as an impudent youth while I was growing up. But I was sixteen when you left home.’ Sixteen when I kissed you with all the fervour and love that was filling me and you used me and brushed me aside. Was I simply too unskilled for you or too foolishly clinging?

A shadow darkened the mocking eyes and for a moment Alistair frowned as though chasing an elusive memory.

But he doesn’t seem to remember—or he is not admitting it. But how could he forget? Perhaps there have been so many women that one inept chit of a girl is infinitely forgettable.

‘Sixteen? Were you?’ He frowned, his eyes intent on her face. ‘I don’t … recollect.’ But his eyes held questions and a hint of puzzlement as though he had been reminded of a faded dream.

‘There is no reason why you should.’ Dita pulled her hand free, dropped the merest hint of a curtsy and walked away. So, he doesn’t even remember! He broke my foolish young heart and he doesn’t even remember doing it. I was that unimportant to him.

Daniel Chatterton intercepted her in the middle of the room and she set her face into a pleasant smile. I am not plain any more, she told herself with a fierce determination not to run away. I am polished and stylish and an original. That is what I am: an original. Other men admire me. It is good that I have met Alistair again—now I can replace the fantasy with the reality. Perhaps now the memories of one shattering, wonderful hour in his bed would leave her, finally.

‘Never tell me that you do not idolise our returning adventurer, Lady Perdita.’ Apparently her expression was not as bland as she hoped. She shrugged; no doubt half the room had heard the exchange. She could imagine the giggles amongst the cattery of young ladies. Chatterton gestured to a passing servant. ‘More punch?’

‘No. No, thank you, it is far too strong.’ Dita took a glass of mango juice in exchange. Was the arrack responsible for how she had felt just now? Without it perhaps she would have seen just another man and the glamour would have dropped away, leaving her untouched. As she raised her drink to sip, she realised her hand retained the faintest hint of Alistair’s scent: leather, musk and something elusive and spicily expensive. He had never smelled like that before, so complex, so intoxicating. He had grown up with a vengeance. But so had she.

‘If you mean Alistair Lyndon, the insolent creature who spoke to Miss Heydon and me just now, I knew him when he was growing up. He was a care-for-nothing then and it seems little has changed.’ Now she was blushing again. She never blushed. ‘He left home when he was twenty, or thereabouts.’

Twenty years, eleven months. She had bought him a fine horn pocket comb for his birthday and painstakingly embroidered a case for it. It was still in the bottom of her jewel box where it had stayed, even when she had eloped with the man she had believed herself in love with.

‘He is Viscount Lyndon, heir to the Marquis of Iwerne, is he not?’

‘Yes. Our families’ lands march together, but we are not great friends.’ Not, at least, since Mama was careless enough to show what she thought of the marquis’s second wife, who was only five years older than Dita. With some friction already over land, and no daughters in the Iwerne household to promote sociability, the families met rarely and there was no incentive to heal the rift.

‘Lyndon left home after some disagreement with his father about eight years ago,’ she added in an indifferent tone. ‘But I don’t think they ever got on, even before that. What is he doing here, do you know?’ It was a reasonable enough question.

‘Joining the party for the Bengal Queen passengers. He is returning home, I hear. The word is that his father is very ill; Lyndon may well be the marquis already.’ Chatterton looked over her shoulder. ‘He is watching you.’

She could feel him, like the gazelle senses the tiger lurking in the shadows, and fought for composure. Three months in a tiny canvas-walled cabin, cheek by jowl with a man who still thrived, she was certain, on dangerous mischief. It wouldn’t be frogs in pinafore pockets these days. If he even suspected how she felt, had felt, about him, she had no idea how he would react.

‘Is he, indeed? How obvious of him.’

‘He is also watching me,’ Chatterton said with a rueful smile. ‘And I do not think it is because he admires my waistcoat. I am beginning to feel dangerously de trop. Most men would pretend they were not observing you—Lyndon has the air of a man guarding his property.’

‘Insolent is indeed the word for him.’ He did not regard her as his property, far from it, but he had bestowed his attention upon her just now and she had snubbed him, so he would not be satisfied until he had her gazing at him cow-eyed like all the rest of the silly girls would do.

Now Dita turned slightly so she was in profile to the viscount and ran a finger down Daniel Chatterton’s waistcoat. ‘Lord Lyndon might not admire it, but is certainly a very fine piece of silk. And you look so handsome in it.’

‘Are you flirting with me by any chance, Lady Perdita?’ Chatterton asked with a grin. ‘Or are you trying to annoy Lyndon?’

‘Me?’ She opened her eyes wide at him, enjoying herself all of a sudden. She had met Alistair again and the heavens had not fallen; perhaps she could survive this after all. She gave Daniel’s neckcloth a pro-prietorial tweak to settle the folds, intent on adding oil to the fire.

‘Yes, you! Don’t you care that he will probably call me out?’

‘He has no cause. Tell me about him so I may better avoid him. I haven’t seen him for years.’ She smiled up into Daniel’s face and stood just an inch too close for propriety.