Полная версия:

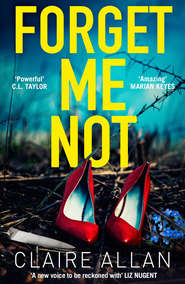

Forget Me Not

Copyright

Published by AVON

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Claire Allan 2019

Cover design © Claire Ward, HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photographs © Karina Vegas/ Arcangel (shoes and background), Shutterstock.com (knife and flowers)

Claire Allan asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008321918

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008321925

Version: 2019-04-26

Praise for Claire Allan:

‘Amazing. I read it in one go.’

Marian Keyes

‘Utterly addictive! Literally couldn’t put it down all day! Compulsive, twisty, tense. And LOVED the ending.’

Claire Douglas

‘A powerful and emotional psychological thriller that will keep you guessing and leave you breathless.’

C.L. Taylor

‘SUCH a good read! It made me feel so uncomfortable, but I still kept gobbling up the pages.’

Lisa Hall

‘Her Name Was Rose is one heck of a read! It’s a psychological thriller with a heart; it’s taut, emotionally challenging and, unlike so many thrillers, each twist and turn is here because it deserves to be and not for the sake of it.’

John Marrs

‘An exciting debut that I couldn’t put down, Her Name Was Rose got under my skin in a way I wasn’t expecting. An intriguing and menacing page turner.’

Mel Sherratt

‘The depth of characterisation and its fast pace is what makes Her Name Was Rose stand out as a thriller. It had me hooked until the end.’

Elisabeth Carpenter

‘A tight and twisted tale with a set of seriously complex characters – kept me guessing right ’til the end. This is going to be one of 2018’s smash hits.’

Cat Hogan

‘All I can say is wow! Such a great concept, expertly delivered to keep you turning the pages. This book toys with the reader until the last page. Trust me, this will be THE book of 2018!’

Caroline Finnerty

‘A brilliantly paced, intriguingly plotted and thoroughly enjoyable story. One of the best psych thrillers I’ve read this year.’

Liz Nugent

‘I devoured it in a couple of days. Claire Allan managed to maintain an unsettling sense of unease that started at the very beginning and didn’t let up at all.’

Elle Croft

‘A superior psychological thriller with an intriguing set-up, a flawed heroine and some great twists. Recommended!’

Mark Edwards

‘Claire Allan’s transition into crime writing is seamless. Her Name Was Rose brings all the emotional heft and depth of characterisation her readers would expect, but with a taut, menacing plot line. A compulsively thrilling read from start to finish.’

Brian McGilloway

‘Mesmerizing to the point of complete distraction. I was totally engrossed in this book.’

Amanda Robson

‘I loved it. The plot is twisty and the issues being dealt with here are big scale but told beautifully through Emily. Her envy and confusion is so real as to be palpable and of course, all too relatable. Creepy and weepy.’

Niki Mackay

‘Claire’s thrillers are twisty like tornadoes.’

Liz Nugent

‘Fantastic, fluid and engaging, a 2019 hit!’

Jo Spain

‘A brilliant and hooky read.’

Fionnuala Kearney

‘A first-rate psychological thriller. Emotional and twisty, with excellent characterisation.’

Patricia Gibney

Dedication

For Julie-Anne, Vicki & Fionnuala

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for Claire Allan

Dedication

Prologue

Wednesday, 6 June

Chapter One: Elizabeth

Chapter Two: Rachel

Chapter Three: Elizabeth

Chapter Four: Rachel

Chapter Five: Rachel

Chapter Six: Elizabeth

Chapter Seven: Rachel

Thursday, 7 June

Chapter Eight: Rachel

Chapter Nine: Elizabeth

Chapter Ten: Rachel

Friday, 8 June

Chapter Eleven: Rachel

Chapter Twelve: Elizabeth

Chapter Thirteen: Rachel

Chapter Fourteen: Rachel

Saturday, 9 June

Chapter Fifteen: Elizabeth

Chapter Sixteen: Rachel

Chapter Seventeen: Rachel

Chapter Eighteen: Elizabeth

Chapter Nineteen: Rachel

Chapter Twenty: Rachel

Chapter Twenty-One: Elizabeth

Chapter Twenty-Two: Rachel

Chapter Twenty-Three: Rachel

Sunday, 10 June

Chapter Twenty-Four: Elizabeth

Chapter Twenty-Five: Rachel

Monday, 11 June

Chapter Twenty-Six: ‘Warn them’

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Rachel

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Elizabeth

Tuesday, 12 June

Chapter Twenty-Nine: Rachel

Chapter Thirty: Rachel

Chapter Thirty-One: Elizabeth

Chapter Thirty-Two: Rachel

Chapter Thirty-Three: Rachel

Chapter Thirty-Four: Rachel

Chapter Thirty-Five: Elizabeth

Chapter Thirty-Six: Rachel

Chapter Thirty-Seven: Elizabeth

Chapter Thirty-Eight: Rachel

Chapter Thirty-Nine: Elizabeth

Wednesday, 13 June

Chapter Forty: Rachel

Chapter Forty-One: Rachel

Chapter Forty-Two: Rachel

Chapter Forty-Three: Elizabeth

Chapter Forty-Four: Rachel

Chapter Forty-Five: Rachel

Thursday, 14 June

Chapter Forty-Six: Rachel

Chapter Forty-Seven: Elizabeth

Chapter Forty-Eight: Rachel

Chapter Forty-Nine: Elizabeth

Chapter Fifty: Rachel

Chapter Fifty-One: Elizabeth

Chapter Fifty-Two: Rachel

Chapter Fifty-Three: Rachel

Chapter Fifty-Four: Elizabeth

Saturday, 16 June

Chapter Fifty-Five: Rachel

Wednesday, 20 June

Epilogue: Rachel

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Claire Allan

About the Publisher

Prologue

I disappeared on a Wednesday afternoon, in June, right in the middle of the heatwave. I was there one minute and the next I was gone. You might think it hard to disappear in broad daylight. To be visible and then, just seconds later, to be invisible. To have a life, and then moments later to have lost it. It wasn’t hard at all.

It was much too easy.

They found my shoes. Well, one of them, turned upside down and covered in dust. They found my car, unlocked. The driver’s window down. My keys in the ignition. My weekly shop melting and rotting in the boot. Cooking in the unspeakable heat.

They found my bag, my purse, my bank cards. My phone. The memorial card with my mother’s picture on it and some rhyming words of comfort, which were supposed to make me feel better about the fact she’d died of breast cancer in her sixties.

They found traces of blood – mine – on the ground outside. Minute droplets. They found traces of unidentified seminal fluid on the back seat, too. Not my husband’s profile. Evidence of a sexual assault, maybe?

Or maybe not.

Scuff marks on the ground, the ground kicked up. Vomit on the patchy, faded tarmac. Smeared fingerprints – mine.

Signs of a struggle.

Half a packet of Wotsits crisps, crushed into the floor of where the rear seats are. An empty Fruit Shoot bottle – blackcurrant – under the passenger seat. An ankle sock. Pink trim. A booster seat in the front of my car.

Signs I was a mother.

‘She wouldn’t leave the baby,’ they said. The baby was three. Blonde curls and blue eyes. Cupid bow lips. A dimple in her left cheek. I wouldn’t leave the baby, they were right. Not unless I had no choice.

I’d been given no choice.

Chapter One

Elizabeth

Even with every window open, this house is still too warm. It’s only half past five in the morning and I know there will be no reprieve from this heatwave. It didn’t cool more than a few degrees overnight and I’ve not slept properly in days. Izzy looked at me mournfully, big brown eyes, pleading for the chance to run about outside before the heat becomes oppressive. I feel sorry for her – even though she’s shed her winter coat, it’s much too warm for her. Like me, she’s become a virtual prisoner in our home.

We’d changed our walking routine a few weeks before. Setting out early now. Before six. Doing our best to avoid the full heat of the sun, though the temperature didn’t seem to drop much overnight. This heatwave was stronger than any I remembered in my lifetime. Even warmer than 1976. That morning I was tired, though. My bones ached and I felt every one of my sixty-seven years, and then some. Still, I’d be back at home within an hour, I reasoned, and I could spend the rest of my morning doing what I had planned – baking bread for my grandchildren, who were coming here after school. I eyed the bananas on the worktop – brown spots seeming to multiply with every hour that passed. I might even throw a quick banana bread in the oven. With chocolate chips. The children would love that.

I had to leave the dough for the bread to prove for another hour anyway – wrapped in clingfilm in the airing cupboard – so I had no excuse but laziness and the persistent ache in my left arm. It hadn’t been the same since it had been broken eighteen months earlier and was, according to the doctor, unlikely to improve further. I’d just have to work through it.

‘Come on, then,’ I called to the dog, who started to wag her tail with great enthusiasm. ‘You win. Just like you always do.’

She bounced her way down the hall, deliriously happy at seeing her lead in my hand. Patting my pockets to make sure I had everything I needed with me – phone, keys, poo bags – I opened the door then watched as Izzy bounded to the end of the garden before stopping, looking back at me and waiting. She was a good dog. She made me leave the house at least once a day, which was a positive thing. I could quite happily have never left the safety of my own home. I preferred my own company. Peace and quiet. My solitary routine. But fresh air was good for body and soul. Or so they said.

I clipped Izzy’s lead to her collar and off we set along Coney Road, narrow, quiet, just far enough from the main roads of Derry to feel as if we were in the middle of nowhere. We’d walk half an hour out on the road and half an hour back, taking in some of the back roads, maybe slip into the country park for a bit.

Striding out, I didn’t put my earphones in. I preferred to be able to hear what was around me. To keep my wits about me, just in case. I doubt I posed an attractive prospect to any would-be kidnapper, rotund and in my mid-sixties, but nonetheless, you never could be too careful. People who wanted to hurt others would do so regardless.

I was glad I’d brought a bottle of water with me. It didn’t take long for me to feel too hot. I chided myself for bringing a jacket. Even though it was light, it was still too heavy for this weather. Everything was too heavy for this weather.

I slipped it off and tied it around my waist. There was a beautiful calm to the morning. The sound of birds tweeting. In a while the city would start to wake up and the rat race would begin again. I was so glad to be out of that now.

After a while, I let Izzy off the lead. She ran on, occasionally stopping to look back at me, teeth flashing a bright canine smile, before setting off again. Occasionally, she’d spot a rabbit or a bird and would speed off up the road, or into the fields to chase them – bounding as she ran. It was then I felt guilty for wanting to stay inside and not walk her. This was where she was at her happiest.

She never wandered far enough that I couldn’t see her. She’d reach a certain point and stop, then turn her head back to me as if to say: ‘Come on, old girl! Keep up.’ She’d wait patiently until I was closer, then set off again.

We walked on until she started barking, running to the hedgerow, yelping and spinning around – running back to me and back to the hedgerow again.

‘What is it, girl?’ I asked as I followed her, wondering what it was she’d uncovered this time: an old ball, ripe for throwing into the field for a prolonged game of catch, or more likely a bone, or the remains of an animal that she’d then roll in, necessitating me wrestling her into the bath when we got home.

Only as I got closer, I saw her pull at something bright. Orange. Fabric. Whatever it was, it was heavy. She pulled and struggled with it, yelping all the time. Despite the heat, I felt a chill run up my spine. I wanted to turn around and run, but Izzy was becoming more and more distressed.

The orange object took shape before my eyes. Sharpened. Came into focus. As did a hand, bluish grey. Izzy pulled back. I noticed her white paws, which just minutes before were brown with mud, were now a dark red. Her barking had become whimpering. I wanted to run but I couldn’t. I was frozen to the spot.

I pulled my phone from my pocket, took a deep breath. Forced myself to keep walking. Before I even reached the crumpled wreck of a body curled in the hedgerow, I’d dialled 999. Asked for help. Police, yes. Ambulance, yes. Was the person breathing? I didn’t know, I wasn’t close enough, but I had to be now. I had to get close. I saw a face, blue, a gaping neck wound. Fibrous tissue, muscle and cartilage all on display. An arm that lay at a strange angle. Dried blood. Fresh blood.

Surely this figure before me was dead. Surely no one could survive such butchery.

‘It’s a woman. A girl,’ I blurted down the phone.

‘Is she breathing?’ The voice on the other end of the line was the calm to my panic.

‘I don’t think so.’

I got down on my knees, repulsed by the sight in front of me but knowing I at least had to check. I had to do what I could. I bent my head down over her body, my ear to her mouth – senses primed to pick up even the slightest whisper of breath. I took her poor, cool wrist in my hand – tried to feel for a pulse. I was shaking. Trying to push away the memories of another time. Other girls. Other men. Other children. Cold and grey and mutilated. This was why I stayed away. The thumping of my heart drowned out all noise, even the yelping of the dog at my feet.

But there it was. The faintest pulse. Thready. Slow. The softest exhalation. Short. Shallow.

‘She’s alive,’ I said to the operator. ‘But only just. Be quick.’

I untied my jacket, placed it on her – as useless as it probably was. Even though it was already hot, she was so cold. The bleeding from her neck wound had been profuse but it had slowed now. I lifted the jacket, moved it and pressed against the wound, almost afraid that I’d press too hard, that my hand would slip inside it.

‘Help’s on the way,’ I said, for my own benefit as much as for that of the unknown woman in front of me. ‘If you can hang on, help is on the way. I’m Elizabeth and I’m not going to leave you. I’m going to be here until the paramedics arrive. So if you could do me a favour and just hang on, that would be great, lovey. It really would.’

I took her hand in mine. Could barely countenance how it could feel so cold and still have life in it.

‘You’re not alone,’ I told her, trying to reassure her.

I wondered who she was and who she belonged to. She wasn’t wearing a wedding ring. There didn’t appear to be much at all distinguishing about her. It was hard to tell the true colour of her hair, matted as it was with mud and blood. If I had to guess, I’d have put her in her mid to late thirties. But it was hard to tell given how bruised and battered she was. Her toenails were painted bright green. It looked so gaudy against the mottled, discoloured skin of her feet – the large areas of raw flesh, gravel-speckled flesh where it looked as though she’d been dragged along the ground, her ankle pointing in the wrong direction.

Someone had wanted this woman very much dead. Someone had left her here. On this quiet country lane, bleeding out.

I could hardly believe she was still alive.

‘You keep fighting,’ I told her. ‘You hold on and keep fighting.’

I was shivering then. Shock was kicking in. My muscles were seizing. I rubbed my arms, tried to release the spasms. Kept an eye out for any traffic that might pass. An ear out for the sound of sirens. Any sound of an approaching police car or ambulance.

I both wished I’d stayed at home and was grateful I was here – at least she had a chance. However small. I put my ear to her mouth again, listened for those shallow breaths. Almost imperceptible but still there. I heard a small gurgle. A rattle. The words ‘Warn them’ carried on the last of her breaths.

Then she was silent. Still.

And I could hear the sirens approaching.

Chapter Two

Rachel

I saw the news on Twitter first: ‘Body of woman found on Derry outskirts.’ It linked to a short article in the Derry Journal saying little more than the headline. Police were at the scene. The Coney Road, from Culmore Point onwards, was closed until further notice. There would be more on this story as it broke.

I felt a shiver run through me. Was it a hit and run, maybe? Oh, God, I hoped it wasn’t a paramilitary attack. No one wanted a return to those days.

No matter the reason, someone would be getting bad news. I shuddered. This woman – she could be a mother, a sister, a friend. Some poor family was about to have their whole world turned upside down.

It was just another reminder that life was short – too bloody short – and as clichéd as it sounds, we don’t know what lies around the corner for any of us. If I’d known this time last year what the following twelve months would bring I might have run away or hidden under my duvet and refused to come out.

I would have wanted to hit pause, but of course I couldn’t. The world kept turning anyway – even though I felt mine had ended with the death of my mother – sixty-five. No age at all. Breast cancer.

I hated that when I talked about her to new people now, the conversation always seemed to wind its way round to how she died. Like it defined her. That final, stupid, too-short battle. Surely everything else she’d done in her life should have mattered more?

I slid my phone back into my bag and along with it I buried my emotions for now. I had to get in front of a classroom of thirty demob-happy youngsters and keep them focused.

At lunchtime, in the staffroom, I pulled my phone from my bag again. Switched it on and looked at it. No substantial updates from the Derry Journal except a photo from the scene – dark hedgerows, bright sunshine. In the distance, beyond the bright yellow, almost festive police tape, there was an ambulance and what looked like the top of one of those white forensic police tents.

Local political representatives were expressing their ‘shock and sadness’, all of them saying it was important not to jump to conclusions until the police had more information. All the police had said so far was that the road would remain closed for some time and that they were appealing for witnesses in relation to the ‘fatality’.

‘We’re appealing for anyone who travelled along the Coney Road on the evening of 5 June or the early hours of 6 June who may have seen any unusual activity to come forward and speak to police.’

I clicked out of the link, tried to join in the chat around the table. The looming end of term meant it wasn’t just the pupils who were feeling giddy at the thought of the long summer break. Still, this news story had brought a sombre feel to the classroom.

‘It’s awful,’ I heard Mr McCallion, one of the geography teachers, say. ‘I heard, from someone who knows these things, that it looks like a murder. A particularly gruesome one at that.’

‘What?’ Ms Doherty, our young, quirky, opinionated art teacher chimed in. ‘Like, is there any kind of a murder that isn’t gruesome? The two tend to go hand in hand,’ she said with a roll of her eyes and a smile that showed she was amused at her own wit.

‘I don’t think us gossiping about it is very appropriate,’ I snapped.

I couldn’t help it. The feeling that some poor woman had lost her life shouldn’t be the subject of staffroom banter. Maybe my own grief had made me raw to it all. Ms Doherty said nothing, but the look she gave me spoke a thousand words. She thought I was a killjoy, a fuddy-duddy. Someone bereft of ‘craic’. She hadn’t known me before my mother died. Before I’d been changed, utterly.

My phone beeped again with a text message from one of my oldest friends, Julie:

Have you heard anything from Clare? She didn’t go into work today. I called round her flat but there was no answer and her phone is off. You know, it’s not like her – and there’s been that woman found …

Julie was always prone to drama and tended to jump directly to the worst possible conclusion about everything, but this time a nagging, sickening feeling started to wash over me. Julie, Clare and I had remained the very best of friends after we’d left school. While I’d trained to teach English, they’d both joined the Civil Service and worked for the Pensions Department on Duke Street. They didn’t do anything without the other knowing.