Полная версия:

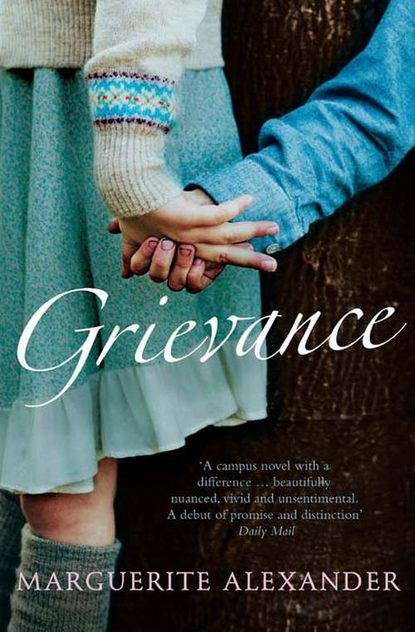

Grievance

Grievance

Marguerite Alexander

For Rachel, Chloë, Hannah and Tom

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

PART ONE Animals

London

Ballypierce

PART TWO Servants

London

Ballypierce

PART THREE Rituals and Meaning

London

Ballypierce

PART FOUR Ecstasy and Longing

London

Ballypierce

PART FIVE The Slaying of the Father

London

Ballypierce

PART SIX Understanding Women

London

Ballypierce

PART SEVEN Exile

London

Ballypierce

EPILOGUE

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

London

It is, Steve supposes, the particular quality of the September afternoon that makes the group so picturesque. The air is so still that the few leaves that are ready to fall drift to the ground with a kind of languor, their colours, in their slow descent, caught in the slanting rays of the sun. It was to enjoy the effect that Steve had lingered; otherwise he might not have noticed the young people at all. There are about half a dozen, mostly seated, one or two of the young men lying, under the handsome chestnut tree in the college quadrangle.

A picnic seems to be in progress. A woollen rug is spread on the grass, dotted with plates of food and large jugs of Pimm’s, its colour harmonising with the autumnal tones of the setting. It must be somebody’s birthday, or perhaps a celebration of reunion at the beginning of the new academic year. Their clothes are unusually bright for undergraduates and one of the girls, who is wearing a floral printed summer dress, has some kind of wreath on her long, crinkly red hair. As Steve watches, she picks up the jug and fills the glasses that stretched arms hold out to her. None of the group is familiar to him, but he’s just returned after a year’s sabbatical and is unlikely to recognise students he doesn’t teach.

He is just about to move on when one of the reclining young men suddenly sits bolt upright and, as he speaks, waves his long, gangly arms in the air. Steve is too far away to catch what he has said, but the gales of laughter that greet the young man’s performance drift across the quad towards him. He smiles to himself, shut off from the joke but pleased by the scene.

He is just about to move on to his office when another group of young people, equally striking but quite different from the first, claims his attention. With an immediate feeling of revulsion, quickly followed by shame, Steve realizes that a number of this second group have a severe mental handicap. They roll their heads and mutter to themselves, apparently indifferent to their surroundings. It seems that, left to themselves, they would shuffle aimlessly along, but the expedition is given an air of purpose by the others, young helpers who are all linked by the arm to their special charges, whom they are guiding across the quad. There is a young woman with Down’s syndrome, whose shoulder-length silky light-brown hair briefly reminds him of his daughter, Emily, but this one point of resemblance heightens the cruelty of the contrast between them. He takes in her face, its tiny features puckered with anxiety; her hands, clutching the arm of the athletic young woman who is leading her; the large thighs and buttocks in the shapeless tracksuit bottoms. Then he turns away, finding his own curiosity inappropriate.

He can’t think what they might be doing here. He wonders whether, in his absence, his colleagues have initiated some outreach programme, possibly attracting government money. It’s the kind of well-meaning, but ultimately pointless, scheme that a junior minister might consider worthy of funding. Unless it’s an initiative by one of the student Christian groups. His interest withers, as it always does, at the thought of active religious commitment (but only in this context: religion as an expression of nationalism or oppression or political discontent is another matter entirely).

Because he doesn’t want to cut across the slow, straggling line, he switches direction and makes a loop that brings him closer to the party of picnickers and, for the first time, notices a girl who, from his earlier position, had been partly obscured. She is more simply and austerely dressed than the others, in white T-shirt and black jeans, small, slender, finely moulded and delicately featured, with the kind of colouring – black hair, blue eyes and pale, almost white skin – that immediately makes his heart leap.

He is particularly struck by her attitude. She is kneeling, body upright from the knees, looking intently away from her friends. Steve slows down and sees that she is following the progress of the last pair in the group crossing the quad.

At first he thinks that her interest is in the young guide, so unlikely does it seem that an educated girl of her generation would stare so blatantly at someone with an obvious mental handicap. The young man is tall, fair-haired, tanned and would, Steve imagines, gaze deep into the eyes of anyone prepared to listen and tell them how much God loves them. He feels a vague resentment that such a remarkable girl should squander her attention on such an unworthy object.

Almost immediately, however, he decides he’s mistaken. To his practised eye, her manner does not suggest sexual interest. He looks as closely as he can at the muscular Christian’s partner, who is on the far side and can only be seen in profile. He, too, is tall and fair-haired, but his features, like those of the girl who reminded him of Emily, are marked by Down’s syndrome. Their arms are linked, but the arrangement seems purely mechanical, the one showing no awareness of the other’s presence.

Steve’s attitude to the guide changes to respect, particularly for his attempts to interest his charge in their surroundings. His free arm is busy indicating points of interest in the quad and he keeps up a steady flow of conversation, but the other boy’s head remains averted, whether or not as a deliberate snub, it’s impossible to say. Then as the pair, who have been drifting away from the rest of the group, turn to catch up, Steve sees that the boy with Down’s syndrome is holding a long chiffon scarf in a brilliant pink. Never taking his eyes off the scarf, and with remarkably deft and practised movements, he waves it in an elaborate series of loops to produce an effect of some beauty.

Steve supposes it was the scarf that caught the girl’s eye, and then she became mesmerised by the performance. Still a puzzle remains, that she should find the boy so compelling that she forgets her friends and the party taking place around her. He is struck by the irony: he has been transfixed by the girl, who shows no awareness of his presence, while the boy, who has eyes only for his scarf, absorbs her.

Then suddenly this long, suspended moment, to which the still September air and slanting rays of golden sunshine have contributed, is broken. The young man and the boy with the scarf are gone, along with the rest of their group. And the young woman has dropped back on her heels and turned to her friends, who now seem to Steve noisy, even raucous, after the intense quiet of the boy and the girl who was watching him. He turns away in the direction of his office.

As the afternoon slides into memory, Steve comes to see it as marking the end of his sabbatical, gaining importance with the new turn of events. But memory can be treacherous. What stays in the mind is the girl, for whom everything else becomes merely setting – not just the chestnut tree and the early-autumn sunshine, but her friends too. In the manner of sheep and goats, they serve to emphasise her difference: her apartness, her seriousness and her intensity.

Her beauty is striking enough against her own immediate background, but when the other young people, so cruelly served by nature, are brought into play, it acquires iconic value. What he forgets, as the days pass, is her mysterious absorption in the boy with the pink chiffon scarf. It may be that it’s beyond his scope to see someone so signally lacking in beauty and intelligence as capable of meaning.

In responding as he does, reordering and refiguring the world according to unexamined prejudices, he makes a fatal error, one that he is always careful to warn his students against. He ignores the context in which he first saw the girl, all those other elements in the scene that are crucial to understanding. And context, as he has spent so much of his professional life arguing, is different from background, which gives the central object transcendent status, encouraging the interpreter to impose his own meaning.

Meanwhile Steve picks up the threads of his professional life and falls back into patterns and routines. There is his new undergraduate course on Irish literature to think about. He has his first sessions with two new doctorate students, both too awed by his reputation to do more than mouth the platitudes into which his own once groundbreaking work has fossilised. There are emails and letters to answer and papers to read, but while he dispatches everything with his usual efficiency, he feels himself to be only half there, semi-detached from his professional self. This isn’t just because he’s been away from it all. The truth is that, although nobody but his wife Martha yet knows of his plans, he is already planning at least a partial escape, in search of another outlet for his talents, and hopes to make an even bigger impact than, as a young scholar, he made on the academic world.

He’s pulled back sharply into the here and now when Charles Rowe pays his welcome-back call. Just for that moment Steve wishes, as must his colleague, that they were still in the time of Rowe’s beloved Jane Austen when a card left on a platter might do the trick.

Steve knows that it’s Rowe even before he’s in the room. There is a shuffling sound outside the door, the unmistakable signal of Rowe’s approach, then a light, tentative knock, followed by a much louder one, in case the first wasn’t heard, both indications of his unease at the prospect of seeing Steve.

‘Yes, come in.’ Steve turns from his desk as Rowe’s overlarge head twists round the door. He wonders whether, as a boy, his colleague was encouraged to see it as stuffed with brains to compensate for the embarrassment it must have caused.

‘Ah, Steven. Good. You’re here. Excellent.’ The words are carefully articulated, suggesting a stutter, once painfully overcome, which always seems on the verge of returning in Steve’s presence: although they’ve rubbed along well enough together for some time now, it’s clear that Rowe has never recovered from the shock he received when Steve was first appointed to the English department and set about overturning the cherished assumptions of his older colleagues.

This was in the early eighties, the beginning of the Thatcher era, when young men (and a few young women) like Steve brazenly presented themselves as a countercultural revolutionary force. Ignoring much of the traditional canon, Steve required his students to read French critics and philosophers like Foucault and Barthes. Rowe, ever eager to learn, dipped into them himself, and finding the prose impenetrable – an unhappy afternoon spent struggling with one paragraph of Derrida has left painful scars on his memory – dismissed them as rubbish, then found to his dismay that the students lapped them up. When they started quoting what he came to think of as the ‘Gallic wreckers’ in essays he had set, he was at a loss how to grade them.

For Rowe and others of his generation, there was a seismic shift. Literature as a repository of eternal values was dismissed in favour of the idea that it was all culturally determined. Even worse was the thought that some of the most valued works in English were hoodwinking their readers into accepting bourgeois values. Jane Austen came under scrutiny and Rowe had to swallow the bitter pill that Mansfield Park, his own favourite, was not after all about personal morality and religious vocation but slavery. It seemed that the only ‘correct’ way to read a text was to concentrate on those who were ‘marginalised’ (another new concept) by it: colonial subjects, women, homosexuals. And slaves. The forces of righteousness had arrived.

Traditionalists like Rowe, who in the beginning found comfort in dismissing the new critical theories as absurd – ‘the emperor’s new clothes’ was the phrase he used with like-minded colleagues – were soon silenced by Steve. His face had a way of setting in contempt at opinions different from his own, and this induced an acute sense of humiliation in those who had been foolhardy enough to voice them. For one so young, Steve was remarkably confident – a confidence that was rapidly justified by events. His first book sold in numbers previously undreamed-of in academic circles and made him something of a celebrity. Overnight it seemed that the ideas he and others of his generation pioneered had become the new orthodoxy, leaving Rowe and his bewildered colleagues with no choice but to conform.

Once the battle was won, harmony of a sort was restored; since Steve’s early appointment to a professorship, which made him, in hierarchical terms, Rowe’s equal, he has behaved with impeccable courtesy towards him, as he does now, getting to his feet in deference to the older man and ushering him to a chair.

‘Well, just for a few minutes, perhaps,’ Rowe says. ‘Far be it from me to disturb you when you’re h-hard at it.’

Steve tries not to look while Rowe, clutching a stack of papers as justification for his visit, makes his ungainly way to the chair, then sinks into it. His condition seems to have deteriorated rapidly over the past year, since Steve last saw him, if indeed there is a condition, other than the process of ageing. He can’t be more than sixty-three or -four, Steve thinks. Only fifteen years older than I am. Christ.

‘You’re looking very well,’ Rowe says. ‘Restored, if I might say so.’

Steve, who is leaning back against his bookshelves, arms folded and ankles crossed, raises an eyebrow in reply. He’s not sure that he likes the idea of being in need of restoration, of being on the downward side of a curve where his inevitable decline may, from time to time, be halted, but never reversed; where a renewal of youthful vigour, after much-needed restoration, will inevitably be short-lived.

‘Not that you ever…’ says Rowe, hastily. ‘Oh dear, you work so admirably hard that I imagined the break…’ This sentence, too, fails and Rowe lowers his eyes in shame.

‘It was, as you say, restorative,’ says Steve, suddenly relenting. It seems churlish to take out his disaffection on Rowe.

His colleague rewards this small act of kindness with a relieved smile that briefly shows discoloured teeth. ‘Not too much time in the library, I hope?’

‘Some, but I also did the Joyce trail – Dublin, Paris, Trieste, Zürich.’ Steve has always avoided studies of individual writers before, preferring theoretical exposition, accompanied by theatrical sleight-of-hand, to overturn the received meaning of canonical texts. Before his sabbatical, however, he announced his intention to write a book on James Joyce.

‘Ah, I envy you.’ Rowe is beginning to relax, to lose the persecuted expression that he wore on entering the room. ‘Jane Austen doesn’t provide her acolytes with quite the same opportunities for travel.’

‘No, I suppose not. So, what can I do for you, Charles?’ Steve nods in the direction of Rowe’s bundle of papers.

‘Ah, yes,’ says Rowe, leafing through them. ‘Here’s something to get you back into the swing of things. I thought I’d bring you up to date with preparations for the Gender and Ethnicity Conference.’

His manner is shyly confident, that of a man offering a particularly rare treat. His confidence is all the more poignant, or piquant, in view of the battering he has received over the years from the keepers of the new orthodoxies. If anybody is responsible for his present sorry state – his pathetic anxiety to please, his physical deterioration, the stutter that seems always on the verge of returning – then it’s probably Steve himself, in creating a climate in which Rowe has been obliged to conform to ideas that he may not even understand, let alone endorse.

‘That’s very thoughtful of you, Charles,’ Steve says. ‘Leave it with me and I’ll give you my comments as soon as I’ve had the chance to read all the material.’

Rowe fails to respond to Steve’s dismissal. ‘We’ve taken the liberty – or, rather, I’ve taken the liberty – I must take full responsibility here…’ he pauses to send Steve a complicit smile, a sure sign, for all his disclaimers, that he has little doubt of pleasing ‘…to put your name forward for the main session of the conference. Something on Irish ethnicity, perhaps, since that seems to be the direction your interests are taking? I thought some advance publicity for the book – not, of course, that you ever need…’

No, I don’t, thinks Steve, angry even while knowing that Rowe means no harm. His reputation alone is enough to guarantee all the publicity he needs. Besides, the department ought to be able to see that he’s moved beyond giving a paper at any conference Rowe is capable of organising. Of course, his name is associated with these ideas – his book on critical theory, although published twenty years ago, is still included on reading lists, not just for literature but for history and anthropology students – but now it’s for the foot soldiers to carry on a battle that’s been largely won. It’s true that he’s about to teach a course on Irish literature, but if he has to teach, he might as well amuse himself.

He’s sufficiently in control of his own reactions, and aware of the danger of burning his boats, to say, ‘Thank you, Charles. It’s nice to know I wasn’t forgotten in my absence. But may I think about it? I’d really rather not commit myself to anything until I see how much time I can squeeze out of all this.’ He makes a sweeping movement with his arm that vaguely encompasses the full range of professional duties suggested by the crowded desk. ‘More than anything, I’m anxious to get on with the book.’

Rowe is disappointed, but not crushed. He has suffered so many defeats in the course of his working life, even when, as on this occasion, he is sure that his actions will be welcomed. ‘Of course, Steven. Whatever you think best. If you could let me know in time to find an alternative speaker – if that’s what you decide, of course…’

He struggles to his feet, makes his ungainly way across the room, then pauses at the door and lifts his arm in farewell before leaving.

Steve sinks into his chair and sits for a while with his head in his hands, wondering how he’s going to be able to put in his time until his means of escape materialises. He had embarked on his sabbatical, and his book on Joyce, with the idea of changing direction but without realising how far in a new direction he would be taken. He’d known for a while that the critical revolution he had helped bring about had peaked; that there was no longer any shock value in overturning expectations when, for new generations of students, deconstruction was already commonplace. He had become a victim of his own success. But the nature of that success was, he had come to feel, rather limited.

In the decade and a half since he made his name, public interest in the academy has shifted away from the post-structuralist approach to literature that once tore apart English departments (the new craze is for reading groups, where no expertise is needed to pitch in with an opinion) towards science and the grand narratives of the neo-Darwinians and astrophysicists. The change can be charted through radio talk-shows, where he is no longer a valued guest, in which the hosts, former devotees of the arts, struggle to ask scientists meaningful questions.

At the same time, those of his arts colleagues who have maintained or strengthened their public profiles – for Steve’s weakness is that he craves public recognition, only feels fully alive when he is ahead of his peers – have moved into biography and cultural history (in at least one well-known case, the history of science), where they have found a way of overturning received ideas through a gossipy, personality-driven, accessible approach. If anything short of a miracle is capable of restoring a spring to Rowe’s step, Steve thinks, it would be the knowledge that he, the once formidable champion of the obscure and arcane processes of critical theory, is now weighing the merits of accessibility.

What attracted him to Joyce was the opportunity he saw for a flashy tour de force, a critical and biographical work that mimicked Joyce’s own writing. Through a combination of deep scholarship and a light, knowing manner, he would illuminate Joyce and find his own way back to the talk-show circuit. And there was an additional beauty in his original idea: that it needn’t look like a desperate move to revive a flagging career since it could be presented as a development of his earlier interests. For was not Joyce himself, like many Irish writers, a kind of deconstructionist? And wasn’t the shift in focus to an Irish writer entirely consistent with his own known interest in colonial writing?

It certainly wasn’t a disadvantage, in his original calculations, that Ireland had become a fashionable topic, not just for former colonial oppressors but, it seemed, globally: Ireland was the only country in the European Union that all the others could agree to admire, a nation that had transformed itself economically without losing any of its lovableness. A new book on Joyce would be a reminder of a different moment in Irish history and of the persistent literary creativity of the Irish. And it would also launch Steve into a new phase in his career, as commentator on Ireland more generally, an informed outsider with the skills and knowledge to take on Ireland’s new identity.

His motives, while self-interested, were never cynical. He was genuinely engaged by the subject, while the still unresolved situation in Ulster – where his allegiances were and are, of course, with the minority Catholic population – would offer him full scope for the committed political position (on the side of the oppressed, the marginalised, the silenced) with which his name is associated. Once that wider role, to which his book on Joyce would give him access, has been secured.

Then an extraordinary thing happened. During his sabbatical he visited Ireland – Dublin, Galway, Cork, places associated with Joyce and his wife Nora – and fell in love. Not with a person, but with the place and its people. It seemed that all the clichés currently employed for contemporary Ireland, about its dynamism, its vibrancy and vitality, about a young, highly educated population that was comfortable both with ideas and popular culture, about a nation that had thrown off the shackles of the past to forge a new identity, were true. And although he never visited the North, his experience of the Republic confirmed his political sympathy for the Northern Irish Catholics, who had only to free themselves of the last vestiges of colonialism to effect the same transformation.

He felt a euphoria of a kind that was new to him. He had gone to Ireland deeply committed to the theoretical position that had underpinned his work – that there is no such thing as a fixed national character that justifies hostile stereotypes, only a set of characteristics that are a response to historical circumstance – and had the satisfaction of seeing his theories triumphantly vindicated. The drab, pious, inward-looking Ireland that he had visited once as a student and found uncongenial, despite the magnificent literature and a history that could only enlist his sympathy, had disappeared as the people had responded to new opportunities. What had been for Steve an idea had become a romance.