Полная версия:

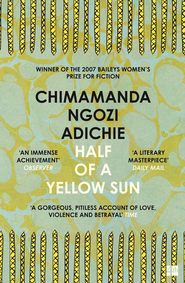

Half of a Yellow Sun

CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE

Half of a Yellow Sun

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This edition published by Harper Perennial 2007

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2006

Copyright © Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, 2006

PS section © Sarah O’Reilly 2007, except ‘The Stories of Africa’ and ‘In the Shadow of Biafra’ by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie © Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie 2007

PS™ is a trademark of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007200283

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2009 ISBN: 9780007279289

Version: 2017-04-26

Contents

Title Page Copyright Dedication Epigraph Part One: The Early Sixties Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Part Two: The Late Sixties Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen Chapter Eighteen Part Three: The Early Sixties Chapter Nineteen Chapter Twenty Chapter Twenty One Chapter Twenty Two Chapter Twenty Three Chapter Twenty Four Part Four: The Late Sixties Chapter Twenty Five Chapter Twenty Six Chapter Twenty Seven Chapter Twenty Eight Chapter Twenty Nine Chapter Thirty Chapter Thirty One Chapter Thirty Two Chapter Thirty Three Chapter Thirty Four Chapter Thirty Five Chapter Thirty Six Chapter Thirty Seven Keep Reading Author's Note P.S. Ideas, interviews & features… About the Author Reviews About the Publisher

Dedication

My grandfathers, whom I never knew,

Nwoye David Adichie and Aro-Nweke Felix Odigwe,

did not survive the war.

My grandmothers, Nwabuodu Regina Odigwe and Nwamgbafor Agnes Adichie, remarkable women both, did.

This book is dedicated to their memories: ka fa nodu na ndokwa.

And to Mellitus, wherever he may be.

Epigraph

Today I see it still –

Dry, wire-thin in sun and dust of the dry months –

Headstone on tiny debris of passionate courage.

– Chinua Achebe,

From ‘Mango Seedling’ in Christmas in Biafra and Other Poems

PART ONE

1

Master was a little crazy; he had spent too many years reading books overseas, talked to himself in his office, did not always return greetings, and had too much hair. Ugwu’s aunty said this in a low voice as they walked on the path. ‘But he is a good man,’ she added. ‘And as long as you work well, you will eat well. You will even eat meat every day.’ She stopped to spit; the saliva left her mouth with a sucking sound and landed on the grass.

Ugwu did not believe that anybody, not even this master he was going to live with, ate meat every day. He did not disagree with his aunty, though, because he was too choked with expectation, too busy imagining his new life away from the village. They had been walking for a while now, since they got off the lorry at the motor park, and the afternoon sun burned the back of his neck. But he did not mind. He was prepared to walk hours more in even hotter sun. He had never seen anything like the streets that appeared after they went past the university gates, streets so smooth and tarred that he itched to lay his cheek down on them. He would never be able to describe to his sister Anulika how the bungalows here were painted the colour of the sky and sat side by side like polite, well-dressed men, how the hedges separating them were trimmed so flat on top that they looked like tables wrapped with leaves.

His aunty walked faster, her slippers making slap-slap sounds that echoed in the silent street. Ugwu wondered if she, too, could feel the coal tar getting hotter underneath, through her thin soles. They went past a sign, ODIM STREET, and Ugwu mouthed street, as he did whenever he saw an English word that was not too long. He smelt something sweet, heady, as they walked into a compound, and was sure it came from the white flowers clustered on the bushes at the entrance. The bushes were shaped like slender hills. The lawn glistened. Butterflies hovered above.

‘I told Master you will learn everything fast, osiso-osiso,’ his aunty said. Ugwu nodded attentively although she had already told him this many times, as often as she told him the story of how his good fortune came about: While she was sweeping the corridor in the Mathematics Department a week ago, she heard Master say that he needed a houseboy to do his cleaning, and she immediately said she could help, speaking before his typist or office messenger could offer to bring someone.

‘I will learn fast, Aunty,’ Ugwu said. He was staring at the car in the garage; a strip of metal ran around its blue body like a necklace.

‘Remember, what you will answer whenever he calls you is Yes, sah!’

‘Yes, sah!’ Ugwu repeated.

They were standing before the glass door. Ugwu held back from reaching out to touch the cement wall, to see how different it would feel from the mud walls of his mother’s hut that still bore the faint patterns of moulding fingers. For a brief moment, he wished he were back there now, in his mother’s hut, under the dim coolness of the thatch roof; or in his aunty’s hut, the only one in the village with a corrugated-iron roof.

His aunty tapped on the glass. Ugwu could see the white curtains behind the door. A voice said, in English, ‘Yes? Come in.’

They took off their slippers before walking in. Ugwu had never seen a room so wide. Despite the brown sofas arranged in a semicircle, the side tables between them, the shelves crammed with books, and the centre table with a vase of red and white plastic flowers, the room still seemed to have too much space. Master sat in an armchair, wearing a singlet and a pair of shorts. He was not sitting upright but slanted, a book covering his face, as though oblivious that he had just asked people in.

‘Good afternoon, sah! This is the child,’ Ugwu’s aunty said.

Master looked up. His complexion was very dark, like old bark, and the hair that covered his chest and legs was a lustrous, darker shade. He pulled off his glasses. ‘The child?’

‘The houseboy, sah.’

‘Oh, yes, you have brought the houseboy. I kpotago ya.’ Master’s Igbo felt feathery in Ugwu’s ears. It was Igbo coloured by the sliding sounds of English, the Igbo of one who spoke English often.

‘He will work hard,’ his aunty said. ‘He is a very good boy. Just tell him what he should do. Thank, sah!’

Master grunted in response, watching Ugwu and his aunty with a faintly distracted expression, as if their presence made it difficult for him to remember something important. Ugwu’s aunty patted Ugwu’s shoulder, whispered that he should do well, and turned to the door. After she left, Master put his glasses back on and faced his book, relaxing further into a slanting position, legs stretched out. Even when he turned the pages he did so with his eyes on the book.

Ugwu stood by the door, waiting. Sunlight streamed in through the windows, and from time to time, a gentle breeze lifted the curtains. The room was silent except for the rustle of Master’s page turning. Ugwu stood for a while before he began to edge closer and closer to the bookshelf, as though to hide in it, and then, after a while, he sank down to the floor, cradling his raffia bag between his knees. He looked up at the ceiling, so high up, so piercingly white. He closed his eyes and tried to reimagine this spacious room with the alien furniture, but he couldn’t. He opened his eyes, overcome by a new wonder, and looked around to make sure it was all real. To think that he would sit on these sofas, polish this slippery-smooth floor, wash these gauzy curtains.

‘Kedu afa gi? What’s your name?’ Master asked, startling him.

Ugwu stood up.

‘What’s your name?’ Master asked again and sat up straight. He filled the armchair, his thick hair that stood high on his head, his muscled arms, his broad shoulders; Ugwu had imagined an older man, somebody frail, and now he felt a sudden fear that he might not please this master who looked so youthfully capable, who looked as if he needed nothing.

‘Ugwu, sah.’

‘Ugwu. And you’ve come from Obukpa?’

‘From Opi, sah.’

‘You could be anything from twelve to thirty.’ Master narrowed his eyes. ‘Probably thirteen.’ He said thirteen in English.

‘Yes, sah.’

Master turned back to his book. Ugwu stood there. Master flipped past some pages and looked up. ‘Ngwa, go to the kitchen; there should be something you can eat in the fridge.’

‘Yes, sah.’

Ugwu entered the kitchen cautiously, placing one foot slowly after the other. When he saw the white thing, almost as tall as he was, he knew it was the fridge. His aunty had told him about it. A cold barn, she had said, that kept food from going off. He opened it and gasped as the cool air rushed into his face. Oranges, bread, beer, soft drinks: many things in packets and cans were arranged on different levels and, at the top, a roasted, shimmering chicken, whole but for a leg. Ugwu reached out and touched the chicken. The fridge breathed heavily in his ears. He touched the chicken again and licked his finger before he yanked the other leg off, eating it until he had only the cracked, sucked pieces of bones left in his hand. Next, he broke off some bread, a chunk that he would have been excited to share with his siblings if a relative had visited and brought it as a gift. He ate quickly, before Master could come in and change his mind. He had finished eating and was standing by the sink, trying to remember what his aunty had told him about opening it to have water gush out like a spring, when Master walked in. He had put on a print shirt and a pair of trousers. His toes, which peeked through leather slippers, seemed feminine, perhaps because they were so clean; they belonged to feet that always wore shoes.

‘What is it?’ Master asked.

‘Sah?’ Ugwu gestured to the sink.

Master came over and turned the metal tap. ‘You should look around the house and put your bag in the first room on the corridor. I’m going for a walk, to clear my head, i nugo?’

‘Yes, sah.’ Ugwu watched him leave through the back door. He was not tall. His walk was brisk, energetic, and he looked like Ezeagu, the man who held the wrestling record in Ugwu’s village.

Ugwu turned off the tap, turned it on again, then off. On and off and on and off until he was laughing at the magic of the running water and the chicken and bread that lay balmy in his stomach. He went past the living room and into the corridor. There were books piled on the shelves and tables in the three bedrooms, on the sink and cabinets in the bathroom, stacked from floor to ceiling in the study, and in the storeroom, old journals were stacked next to crates of Coke and cartons of Premier beer. Some of the books were placed face down, open, as though Master had not yet finished reading them but had hastily gone on to another. Ugwu tried to read the titles, but most were too long, too difficult. Non-Parametric Methods. An African Survey. The Great Chain of Being. The Norman Impact Upon England. He walked on tiptoe from room to room, because his feet felt dirty, and as he did so he grew increasingly determined to please Master, to stay in this house of meat and cool floors. He was examining the toilet, running his hand over the black plastic seat, when he heard Master’s voice.

‘Where are you, my good man?’ He said my good man in English.

Ugwu dashed out to the living room. ‘Yes, sah!’

‘What’s your name again?’

‘Ugwu, sah.’

‘Yes, Ugwu. Look here, nee anya, do you know what that is?’ Master pointed, and Ugwu looked at the metal box studded with dangerous-looking knobs.

‘No, sah,’ Ugwu said.

‘It’s a radiogram. It’s new and very good. It’s not like those old gramophones that you have to wind and wind. You have to be very careful around it, very careful. You must never let water touch it.’

‘Yes, sah.’

‘I’m off to play tennis, and then I’ll go on to the staff club.’ Master picked up a few books from the table. ‘I may be back late. So get settled and have a rest.’

‘Yes, sah.’

After Ugwu watched Master drive out of the compound, he went and stood beside the radiogram and looked at it carefully, without touching it. Then he walked around the house, up and down, touching books and curtains and furniture and plates, and when it got dark, he turned the light on and marvelled at how bright the bulb that dangled from the ceiling was, how it did not cast long shadows on the wall like the palm oil lamps back home. His mother would be preparing the evening meal now, pounding akpu in the mortar, the pestle grasped tightly with both hands. Chioke, the junior wife, would be tending the pot of watery soup balanced on three stones over the fire. The children would have come back from the stream and would be taunting and chasing one another under the breadfruit tree. Perhaps Anulika would be watching them. She was the oldest child in the household now, and as they all sat around the fire to eat, she would break up the fights when the younger ones struggled over the strips of dried fish in the soup. She would wait until all the akpu was eaten and then divide the fish so that each child had a piece, and she would keep the biggest for herself, as he had always done.

Ugwu opened the fridge and ate some more bread and chicken, quickly stuffing the food in his mouth while his heart beat as if he were running; then he dug out extra chunks of meat and pulled out the wings. He slipped the pieces into his shorts’ pockets before going to the bedroom. He would keep them until his aunty visited and he would ask her to give them to Anulika. Perhaps he could ask her to give some to Nnesinachi too. That might make Nnesinachi finally notice him. He had never been sure exactly how he and Nnesinachi were related, but he knew they were from the same umunna and therefore could never marry. Yet he wished that his mother would not keep referring to Nnesinachi as his sister, saying things like, ‘Please take this palm oil down to Mama Nnesinachi, and if she is not in, leave it with your sister.’

Nnesinachi always spoke to him in a vague voice, her eyes unfocused, as if his presence made no difference to her either way. Sometimes she called him Chiejina, the name of his cousin who looked nothing at all like him, and when he said, ‘It’s me’, she would say, ‘Forgive me, Ugwu my brother,’ with a distant formality that meant she had no wish to make further conversation. But he liked going on errands to her house. They were opportunities to find her bent over, fanning the firewood or chopping ugu leaves for her mother’s soup pot, or just sitting outside looking after her younger siblings, her wrapper hanging low enough for him to see the tops of her breasts. Ever since they started to push out, those pointy breasts, he had wondered if they would feel mushy-soft or hard like the unripe fruit from the ube tree. He often wished that Anulika wasn’t so flat-chested – he wondered what was taking her so long anyway, since she and Nnesinachi were about the same age – so that he could feel her breasts. Anulika would slap his hand away, of course, and perhaps even slap his face as well, but he would do it quickly – squeeze and run – and that way he would at least have an idea and know what to expect when he finally touched Nnesinachi’s.

But he was worried that he might never get to touch them, now that her uncle had asked her to come and learn a trade in Kano. She would be leaving for the North by the end of the year, when her mother’s last child, whom she was carrying, began to walk. Ugwu wanted to be as pleased and grateful as the rest of the family. There was, after all, a fortune to be made in the North; he knew of people who had gone up there to trade and came home to tear down huts and build houses with corrugated-iron roofs. He feared, though, that one of those pot-bellied traders in the North would take one look at her, and the next thing he knew somebody would bring palm wine to her father and he would never get to touch those breasts. They – her breasts – were the images saved for last on the many nights when he touched himself, slowly at first and then vigorously, until a muffled moan escaped him. He always started with her face, the fullness of her cheeks and the ivory tone of her teeth, and then he imagined her arms around him, her body moulded to his. Finally, he let her breasts form; sometimes they felt hard, tempting him to bite into them, and other times they were so soft he was afraid his imaginary squeezing caused her pain.

For a moment, he considered thinking of her tonight. He decided not to. Not on his first night in Master’s house, on this bed that was nothing like his hand-woven raffia mat. First, he pressed his hands into the springy softness of the mattress. Then, he examined the layers of cloth on top of it, unsure whether to sleep on them or to remove them and put them away before sleeping. Finally, he climbed up and lay on top of the layers of cloth, his body curled in a tight knot.

He dreamed that Master was calling him – Ugwu, my good man! – and when he woke up Master was standing at the door, watching him. Perhaps it had not been a dream. He scrambled out of bed and glanced at the windows with the drawn curtains, in confusion. Was it late? Had that soft bed deceived him and made him oversleep? He usually woke with the first cockcrows.

‘Good morning, sah!’

‘There is a strong roasted-chicken smell here.’

‘Sorry, sah.’

‘Where is the chicken?’

Ugwu fumbled in his shorts’ pockets and brought out the chicken pieces.

‘Do your people eat while they sleep?’ Master asked. He was wearing something that looked like a woman’s coat and was absently twirling the rope tied round his waist.

‘Sah?’

‘Did you want to eat the chicken while in bed?’

‘No, sah.’

‘Food will stay in the dining room and the kitchen.’

‘Yes, sah.’

‘The kitchen and bathroom will have to be cleaned today.’

‘Yes, sah.’

Master turned and left. Ugwu stood trembling in the middle of the room, still holding the chicken pieces with his hand outstretched. He wished he did not have to walk past the dining room to get to the kitchen. Finally, he put the chicken back in his pockets, took a deep breath, and left the room. Master was at the dining table, the teacup in front of him placed on a pile of books.

‘You know who really killed Lumumba?’ Master said, looking up from a magazine. ‘It was the Americans and the Belgians. It had nothing to do with Katanga.’

‘Yes, sah,’ Ugwu said. He wanted Master to keep talking, so he could listen to the sonorous voice, the musical blend of English words in his Igbo sentences.

‘You are my houseboy,’ Master said. ‘If I order you to go outside and beat a woman walking on the street with a stick, and you then give her a bloody wound on her leg, who is responsible for the wound, you or me?’

Ugwu stared at Master, shaking his head, wondering if Master was referring to the chicken pieces in some roundabout way.

‘Lumumba was prime minister of Congo. Do you know where Congo is?’ Master asked.

‘No, sah.’

Master got up quickly and went into the study. Ugwu’s confused fear made his eyelids quiver. Would Master send him home because he did not speak English well, kept chicken in his pocket overnight, did not know the strange places Master named? Master came back with a wide piece of paper that he unfolded and laid out on the dining table, pushing aside books and magazines. He pointed with his pen. ‘This is our world, although the people who drew this map decided to put their own land on top of ours. There is no top or bottom, you see.’ Master picked up the paper and folded it, so that one edge touched the other, leaving a hollow between. ‘Our world is round, it never ends. Nee anya, this is all water, the seas and oceans, and here’s Europe and here’s our own continent, Africa, and the Congo is in the middle. Farther up here is Nigeria, and Nsukka is here, in the southeast; this is where we are.’ He tapped with his pen.

‘Yes, sah.’

‘Did you go to school?’

‘Standard two, sah. But I learn everything fast.’

‘Standard two? How long ago?’

‘Many years now, sah. But I learn everything very fast!’

‘Why did you stop school?’

‘My father’s crops failed, sah.’

Master nodded slowly. ‘Why didn’t your father find somebody to lend him your school fees?’

‘Sah?’

‘Your father should have borrowed!’ Master snapped, and then, in English, ‘Education is a priority! How can we resist exploitation if we don’t have the tools to understand exploitation?’

‘Yes, sah!’ Ugwu nodded vigorously. He was determined to appear as alert as he could, because of the wild shine that had appeared in Master’s eyes.

‘I will enrol you in the staff primary school,’ Master said, still tapping on the piece of paper with his pen.

Ugwu’s aunty had told him that if he served well for a few years, Master would send him to commercial school where he would learn typing and shorthand. She had mentioned the staff primary school, but only to tell him that it was for the children of the lecturers, who wore blue uniforms and white socks so intricately trimmed with wisps of lace that you wondered why anybody had wasted so much time on mere socks.

‘Yes, sah,’ he said. ‘Thank, sah.’

‘I suppose you will be the oldest in class, starting in standard three at your age,’ Master said. ‘And the only way you can get their respect is to be the best. Do you understand?’

‘Yes, sah!’

‘Sit down, my good man.’

Ugwu chose the chair farthest from Master, awkwardly placing his feet close together. He preferred to stand.

‘There are two answers to the things they will teach you about our land: the real answer and the answer you give in school to pass. You must read books and learn both answers. I will give you books, excellent books.’ Master stopped to sip his tea. ‘They will teach you that a white man called Mungo Park discovered River Niger. That is rubbish. Our people fished in the Niger long before Mungo Park’s grandfather was born. But in your exam, write that it was Mungo Park.’