Полная версия:

Half a King

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2014

Copyright © Joe Abercrombie 2014

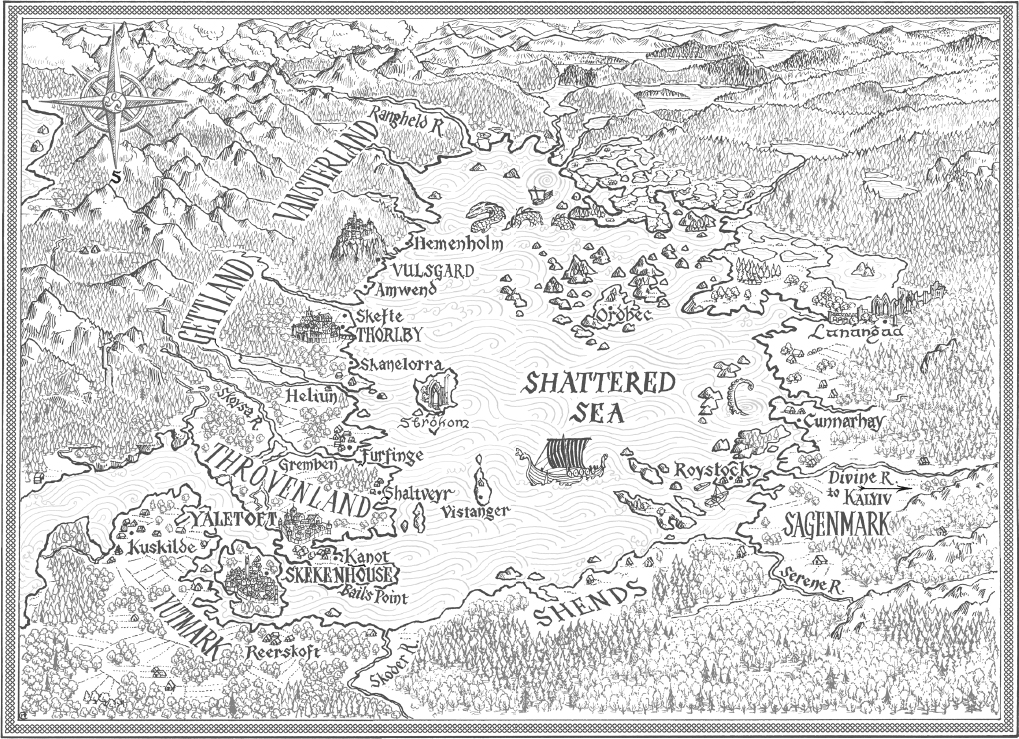

Map copyright © Nicolette Caven 2014

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © iStock (detail of cloaked man); Shutterstock.com (all other images)

Joe Abercrombie asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007550227

Ebook Edition © January 2015 ISBN: 9780007550210

Version: 2017-11-23

Praise for Half a King:

‘Joe Abercrombie does it again. Half a King is another page-turner from Britain’s hottest young fantasist, a fast-paced tale of betrayal and revenge that grabbed me from page one and refused to let go’

GEORGE R.R. MARTIN, author of A Game of Thrones

‘Fast-moving, gritty and violent, Half a King will not disappoint Abercrombie’s legion of followers’

Guardian

‘Another great tale from a master. His medieval, post-apocalyptic land is full of such brilliant banter it would find a laugh at a funeral. It is macabre, menacing and Machiavelli himself would have enjoyed the way half-handed “hero” Yarvi triumphs’

The Sun

‘Enthralling. An up-all-night read’

ROBIN HOBB, author of Fool’s Assassin and the Realm of the Elderlings novels

‘Joe Abercrombie is fast becoming my favourite writer. The action is frenetic, the characters are as sharp as the blades they wield, and the humour is biting’

DEREK LANDY, author of the Skulduggery Pleasant novels

‘As Jarvi gets to know his motley band of renegades, you feel you are meeting real characters underneath the stubble and the grime. It’s this quality that both grounds the fantasy and lifts the book onto another level, so while it grips like a bear hug, it warms like a bear skin’

Daily Mail

‘Half a King is woven with a narrative of delightful cunning as we have come to expect from Joe Abercrombie. This is a “to read in a day” kind of book’

British Fantasy Society

‘Bloody awesome. A must-read’

BEN KANE, author of the Spartacus novels

‘Classic Abercrombie, and yet also something unexpected – grimdark fantasy for people who aren’t necessarily very young’

SFX, 5 Star Review

‘I’ve been a fan of Abercrombie’s stuff for years. His world–building is great, his characterization is marvellous, he writes an amazing action scene. I think this is my favourite Abercrombie book yet. And that’s really saying something’

PATRICK ROTHFUSS, author of The Name of the Wind

‘One of the most gripping books I’ve read for a long time. Once this plot has its teeth in you, it will not let you go’

Fantasy Book Review

‘Abercrombie’s stellar prose style and clever plot twists will be sure to please both adult and teen readers’

Publishers Weekly, Starred Review

‘Half a King isn’t merely equal to Abercrombie’s previous work; it is his finest novel to date and the one that may one day make him a household name’

Tor.com

‘It’s lightning fast and filled with a wonderful collection of rogues, villains and two-faced bastards’

Sci-Fi Now

‘Half a King can be summed up in a single word: Masterpiece … It’s a coming of age story. It’s a Viking saga. It’s a revenge tale and family drama and the return of the prodigal son. But most of all, it’s this: a short time alongside people as weak and blundering as we are, and in the midst of it all, as heroic. What a wonderful book’

MYKE COLE, author of Control Point

‘A gripping novel, structured to keep its tension at a constant nail-biting pitch’

Strange Horizons

‘The author’s economical voice gives a clear and unsentimental account of events sordid, beautiful, or, often, a blend of the two. Abercrombie’s Shattered Sea is a fantastic yet believable backdrop to Yarvi’s struggle, a vivid imaginary land to which both habitual and newly minted grimdark readers will happily return for Half a King’s projected sequels’

Seattle Times

‘Holy crap this is a good book … Half A King is full of all the adventure I’ve come to expect from Abercrombie and a tenderness I never knew he had. There’s infinitely more to Joe Abercrombie than we ever thought’

SAM SYKES, author of Tome of the Undergates

‘The joy of Half a King lies in its simplicity. The story is briskly told but it packs the necessary essentials: treachery, dangerous men, women who are not what they seem, duels, and moral dilemmas’

The Daily Beast

‘Joe Abercrombie’s storytelling is more concise in Half a King and as sharp as ever with wit and deft prose’

Fantasy Book Critic

‘This is as skilful and as enjoyable a read as any Abercrombie I’ve read to date, and often much subtler’

SFFWorld

‘Joe Abercrombie’s Half a King serves as a reminder that there are considerable virtues yet to be found by efficient, on-the-ground storytelling propelled more by plot than by setting, with crisp dialogue, humane characters, and a distinct inward spiral of rapid-fire events’

Locus

‘A sympathetic main character, a fast-paced plot, and plenty of neat world-building. Highly recommended’

io9

Dedication

For Grace

Better gear Than good sense A traveller cannot carry

From Hávamál, the Speech of the High One

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise

Dedication

Map

I: The Black Chair

The Greater Good

Duty

A Way to Win

Between Gods and Men

Doves

Promises

Man’s Work

The Enemy

II: The South Wind

Cheapest Offerings

One Family

Heave

The Minister’s Tools

The Fool Strikes

Savages

Ugly Little Secrets

Enemies and Allies

One Friend

Death Waits

III: The Long Road

Bending with Circumstance

Freedom

The Better Men

Kindness

The Truth

Running

Downriver

Only a Devil

The Last Stand

Burning the Dead

Floating Twigs

IV: The Rightful King

Crows

Your Enemy’s House

Great Stakes

In Darkness

A Friend’s Fight

Mother War’s Bargain

The Last Door

A Lonely Seat

The Blame

Some are Saved

The Lesser Evil

Half the World Excerpt

In Conversation with Joe Abercrombie

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

THE GREATER GOOD

There was a harsh gale blowing on the night Yarvi learned he was a king. Or half a king, at least.

A seeking wind, the Gettlanders called it, for it found out every chink and keyhole, moaning Mother Sea’s dead chill into every dwelling, no matter how high the fires were banked or how close the folk were huddled.

It tore at the shutters in the narrow windows of Mother Gundring’s chambers and rattled even the iron-bound door in its frame. It taunted the flames in the firepit and they spat and crackled in their anger, casting clawing shadows from the dried herbs hanging, throwing flickering light upon the root that Mother Gundring held up in her knobbled fingers.

‘And this?’

It looked like nothing so much as a clod of dirt, but Yarvi had learned better. ‘Black-tongue root.’

‘And why might a minister reach for it, my prince?’

‘A minister hopes they won’t have to. Boiled in water it can’t be seen or tasted, but is a most deadly poison.’

Mother Gundring tossed the root aside. ‘Ministers must sometimes reach for dark things.’

‘Ministers must find the lesser evil,’ said Yarvi.

‘And weigh the greater good. Five right from five.’ Mother Gundring gave a single approving nod and Yarvi flushed with pride. The approval of Gettland’s minister was not easily won. ‘And the riddles on the test will be easier.’

‘The test.’ Yarvi rubbed nervously at the crooked palm of his bad hand with the thumb of his good.

‘You will pass.’

‘You can’t be sure.’

‘It is a minister’s place always to doubt—’

‘But always to seem certain,’ he finished for her.

‘See? I know you.’ That was true. No one knew him better, even in his own family. Especially in his own family. ‘I have never had a sharper pupil. You will pass at the first asking.’

‘And I’ll be Prince Yarvi no more.’ All he felt at that thought was relief. ‘I’ll have no family and no birthright.’

‘You will be Brother Yarvi, and your family will be the Ministry.’ The firelight found the creases about Mother Gundring’s eyes as she smiled. ‘Your birthright will be the plants and the books and the soft word spoken. You will remember and advise, heal and speak truth, know the secret ways and smooth the path for Father Peace in every tongue. As I have tried to do. There is no nobler work, whatever nonsense the muscle-smothered fools spout in the training square.’

‘The muscle-smothered fools are harder to ignore when you’re in the square with them.’

‘Huh.’ She curled her tongue and spat into the fire. ‘Once you pass the test you only need go there to tend a broken head when the play gets too rough. One day you will carry my staff.’ She nodded towards the tapering length of studded and slotted elf-metal which leaned against the wall. ‘One day you will sit beside the Black Chair, and be Father Yarvi.’

‘Father Yarvi.’ He squirmed on his stool at that thought. ‘I lack the wisdom.’ He meant he lacked the courage, but lacked the courage to admit it.

‘Wisdom can be learned, my prince.’

He held his left hand, such as it was, up to the light. ‘And hands? Can you teach those?’

‘You may lack a hand, but the gods have given you rarer gifts.’

He snorted. ‘My fine singing voice, you mean?’

‘Why not? And a quick mind, and empathy, and strength. Only the kind of strength that makes a great minister, rather than a great king. You have been touched by Father Peace, Yarvi. Always remember: strong men are many, wise men are few.’

‘No doubt why women make better ministers.’

‘And better tea, in general.’ Gundring slurped from the cup he brought her every evening, and nodded approval again. ‘But the making of tea is another of your mighty talents.’

‘Hero’s work indeed. Will you give me less flattery when I’ve turned from prince into minister?’

‘You will get such flattery as you deserve, and my foot in your arse the rest of the time.’

Yarvi sighed. ‘Some things never change.’

‘Now to history.’ Mother Gundring slid one of the books from its shelf, stones set into the gilded spine winking red and green.

‘Now? I have to be up with Mother Sun to feed your doves. I was hoping to get some sleep before—’

‘I’ll let you sleep when you’ve passed the test.’

‘No you won’t.’

‘You’re right, I won’t.’ She licked one finger, ancient paper crackling as she turned the pages. ‘Tell me, my prince, into how many splinters did the elves break God?’

‘Four hundred and nine. The four hundred Small Gods, the six Tall Gods, the first man and woman, and Death, who guards the Last Door. But isn’t this more the business of a prayer-weaver than a minister?’

Mother Gundring clicked her tongue. ‘All knowledge is the business of the minister, for only what is known can be controlled. Name the six Tall Gods.’

‘Mother Sea and Father Earth, Mother Sun and Father Moon, Mother War and—’

The door banged wide and that seeking wind tore through the chamber. The flames in the firepit jumped as Yarvi did, dancing distorted in the hundred hundred jars and bottles on the shelves. A figure blundered up the steps, setting the bunches of plants swinging like hanged men behind him.

It was Yarvi’s Uncle Odem, hair plastered to his pale face with the rain and his chest heaving. He stared at Yarvi, eyes wide, and opened his mouth but made no sound. One needed no gift of empathy to see he was weighed down by heavy news.

‘What is it?’ croaked Yarvi, his throat tight with fear.

His uncle dropped to his knees, hands on the greasy straw. He bowed his head, and spoke two words, low and raw.

‘My king.’

And Yarvi knew his father and brother were dead.

DUTY

They hardly looked dead.

Only very white, laid out on those chill slabs in that chill room with shrouds drawn up to their armpits and naked swords gleaming on their chests. Yarvi kept expecting his brother’s mouth to twitch in sleep. His father’s eyes to open, to meet his with that familiar scorn. But they did not. They never would again.

Death had opened the Last Door for them, and from that portal none return.

‘How did it happen?’ Yarvi heard his mother saying from the doorway. Her voice was steady as ever.

‘Treachery, my queen,’ murmured his Uncle Odem.

‘I am queen no more.’

‘Of course … I am sorry, Laithlin.’

Yarvi reached out and gently touched his father’s shoulder. So cold. He wondered when he last touched his father. Had he ever? He remembered well enough the last time they had spoken any words that mattered. Months before.

A man swings the scythe and the axe, his father had said. A man pulls the oar and makes fast the knot. Most of all a man holds the shield. A man holds the line. A man stands by his shoulder-man. What kind of man can do none of these things?

I didn’t ask for half a hand, Yarvi had said, trapped where he so often found himself, on the barren ground between shame and fury.

I didn’t ask for half a son.

And now King Uthrik was dead, and his King’s Circle, hastily resized, was a weight on Yarvi’s brow. A weight far heavier than that thin band of gold deserved to be.

‘I asked you how they died,’ his mother was saying.

‘They went to speak peace with Grom-gil-Gorm.’

‘There can be no peace with the damn Vanstermen,’ came the deep voice of Hurik, his mother’s Chosen Shield.

‘There must be vengeance,’ said Yarvi’s mother.

His uncle tried to calm the storm. ‘Surely time to grieve, first. The High King has forbidden open war until—’

‘Vengeance!’ Her voice was sharp as broken glass. ‘Quick as lightning, hot as fire.’

Yarvi’s eyes crawled to his brother’s corpse. There was quick and hot, or had been. Strong-jawed, thick-necked, already the makings of a dark beard like their father’s. As unlike Yarvi as it was possible to be. His brother had loved him, he supposed. A bruising love where every pat was just this side of a slap. The love one has for something always beneath you.

‘Vengeance,’ growled Hurik. ‘The Vanstermen must be made to pay.’

‘Damn the Vanstermen,’ said Yarvi’s mother. ‘Our own people must be made to serve. They must be shown their new king has iron in him. Once they are happy on their knees you can make Mother Sea rise with your tears.’

Yarvi’s uncle gave a heavy sigh. ‘Vengeance, then. But is he ready, Laithlin? He has never been a fighter—’

‘He must fight, ready or not!’ snapped his mother. People had always talked around Yarvi as though he was deaf as well as crippled. It seemed his sudden rise to power had not cured them of the habit. ‘Make preparations for a great raid.’

‘Where shall we attack?’ asked Hurik.

‘All that matters is that we attack. Leave us.’

Yarvi heard the door closing and his mother’s footsteps, soft across the cold floor.

‘Stop crying,’ she said. It was only then that Yarvi realized his eyes were swimming, and he wiped them, and sniffed, and was ashamed. Always he was ashamed

She gripped him by the shoulders. ‘Stand tall, Yarvi.’

‘I’m sorry,’ he said, trying to puff out his chest the way his brother might have. Always he was sorry.

‘You are a king, now.’ She twisted his crooked cloak-buckle into place, tried to tame his pale blonde hair, close-clipped but always wild, and finally laid cool fingertips against his cheek. ‘You must never be sorry. You must wear your father’s sword, and lead a raid against the Vanstermen.’

Yarvi swallowed. The idea of going on a raid had always filled him with dread. To lead one?

Odem must have seen his horror. ‘I will be your shoulder-man, my king, always beside you, my shield at the ready. However I can help you, I will.’

‘My thanks,’ mumbled Yarvi. All the help he wanted was to be sent to Skekenhouse to take the Minister’s Test, to sit in the shadows rather than be thrust into the light. But that hope was dust now. Like badly-mixed mortar, his hopes were prone to crumble.

‘You must make Grom-gil-Gorm suffer for this,’ said his mother. ‘Then you must marry your cousin.’

He could only stare into her iron-grey eyes. Stare a little upward as she was still taller than he. ‘What?’

The soft touch became an irresistible grip about his jaw. ‘Listen to me, Yarvi, and listen well. You are the king. This may not be what either of us wanted, but this is what we have. You hold all our hopes now, and you hold them at the brink of a precipice. You are not respected. You have few allies. You must bind our family together by marrying Odem’s daughter Isriun, just as your brother was to do. We have spoken of it. It is agreed.’

Uncle Odem was quick to balance ice with warmth. ‘Nothing would please me more than to stand as your marriage-father, my king, and see our families forever joined.’

Isriun’s feelings were not mentioned, Yarvi noticed. No more than his. ‘But …’

His mother’s brow hardened. Her eyes narrowed. He had seen heroes tremble beneath that look, and Yarvi was no hero. ‘I was betrothed to your Uncle Uthil, whose sword-work the warriors still whisper of. Your Uncle Uthil, who should have been king.’ Her voice cracked as though the words were painful. ‘When Mother Sea swallowed him and they raised his empty howe above the shore, I married your father in his place. I put aside my feelings and did my duty. So must you.’

Yarvi’s eyes slid back to his brother’s handsome corpse, wondering that she could plan so calmly with her dead husband and son laid out within arm’s reach. ‘You don’t weep for them?’

A sudden spasm gripped his mother’s face, all her carefully arranged beauty splitting, lips curling from her teeth and her eyes screwing up and the cords in her neck standing stark. For a terrible moment Yarvi did not know if she would beat him or break down in wailing sobs and could not say which scared him more. Then she took a ragged breath, pushed one loose strand of golden hair into its proper place, and was herself again.

‘One of us at least must be a man.’ And with that kingly gift she turned and swept from the room.

Yarvi clenched his fists. Or he clenched one, and squeezed the other thumb against the twisted stub of his one finger.

‘Thanks for the encouragement, Mother.’

Always he was angry. As soon as it was too late to do him any good.

He heard his uncle step close, speaking with the soft voice one might use on a skittish foal. ‘You know your mother loves you.’

‘Do I?’

‘She has to be strong. For you. For the land. For your father.’

Yarvi looked from his father’s body to his uncle’s face. So like, yet so unlike. ‘Thank the gods you’re here,’ he said, the words rough in his throat. At least there was one member of his family who cared for him.

‘I am sorry, Yarvi. I truly am.’ Odem put his hand on Yarvi’s shoulder, a glimmer of tears in his eyes. ‘But Laithlin is right. We must do what is best for Gettland. We must put our feelings aside.’

Yarvi heaved up a sigh. ‘I know.’

His feelings had been put aside ever since he could remember.

A WAY TO WIN

‘Keimdal, you will spar with the king.’

Yarvi had to smother a fool’s giggle when he heard the master-at-arms apply the word to him. Probably the four score young warriors gathered opposite were all stifling their own laughter. Certainly they would be once they saw their new king fight. No doubt, by then, laughter would be the last thing on Yarvi’s mind.

They were his subjects now, of course. His servants. His men, all sworn to die upon his whim. Yet they felt even more a row of scornful enemies than when he had faced them as a boy.

He still felt like a boy. More like a boy than ever.

‘It will be my honour.’ Keimdal did not look especially honoured as he stepped from his fellows and out into the training square, moving as easily in a coat of mail as a maiden in her shift. He took up a shield and wooden practice sword and made the air whistle with some fearsome swipes. He might have been less than a year older than Yarvi but he looked five: half a head taller, far thicker in the chest and shoulder and already boasting red stubble on his heavy jaw.

‘Are you ready, my king?’ muttered Odem in Yarvi’s ear.

‘Clearly not,’ hissed Yarvi, but there was no escape. The King of Gettland must be a doting son to Mother War, however ill-suited he might be. He had to prove to the older warriors ranged around the square that he could be more than a one-handed embarrassment. He had to find a way to win. There is always a way, his mother used to tell him.