скачать книгу бесплатно

“Where?” asked Anne-Marie.

“Aurelia, their farm. We’re invited.”

“Oh,” said Anne. “Why?”

“To celebrate Cal coming home.”

“That’s nice,” she said halfheartedly.

“Leo won’t think so,” her husband muttered in reply, before turning back to read his paper. And so, because he was preoccupied, she didn’t bother to question him, and as usual they finished the remainder of their dinner in silence.

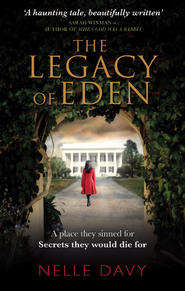

Two weeks later and my grandmother stepped foot on Aurelia for the first time. The place as it was then would be unrecognizable to me: no sign in curlicue lettering, no pockets of flowers, no white house. I have seen pictures of what it used to be like. Instead of the daisies and hyacinths, the entrance to the farm was simply a sandy drive that wove its way along the crab grass. The house on the mound was not white and tall, but gray and flat with dark shutters and a roof that peeked over the front in a slanted fringe. In the distance the grass swept on and on, periodically knotted with thatches of prairie grass until eventually it found the fields of corn and the stream. It was large and expansive and Anne-Marie’s first thought when she saw all of this was that it was ugly.

Did she see everything then that it could be? Did she re-envision the sight before her and see in her mind the potential that could arise from beneath her guiding hand? It would not have surprised us if she had. In fact in some ways it is what we would have expected from her, because in the end the way she knew exactly how to mold the farm to suit her tastes and bring out the beauty in it was almost prophetic. She was so intuitive that we all assumed she must have connected to it from the first. But in truth there was no such feeling. Maybe Lavinia Hathaway would come to feel that way, but in 1946, Anne-Marie Parks did not. Instead, she did not like Aurelia and she hated the idea of going to the party.

It was not the first time this had happened. Her insides had a habit of withering in anxiety whenever she was faced with an event like this. The farm at this point was not the great estate it would come to be in my lifetime, but it was still considered to be a prosperous holding and the Hathaways were a very respected family in the community. Nobody would have missed the party if they could help it and the weight of expectation that was implicit in the invite weighed down on Anne-Marie from the moment her husband had mentioned it to her over dinner. Because no matter what she wore or how many hours she spent on her hair and makeup, she always felt like the unwanted niece of her lawyer uncle, the abandoned child, a product of other people’s charity.

It was as if she had been branded and nothing could remove it. Not seducing and marrying the town doctor; not moving into a house of her own, which was only slightly smaller than her uncle’s. Often she would wonder if this was to be it. If she would live and die as nothing more than the doctor’s wife and her uncle’s former charge. She would think these things as she cooked, or ran her errands, and she would suddenly be consumed with an urge to utterly annihilate everything around her. Once she took the kitchen knife to the soft pink curtains that hung over the window above the sink. She slashed at them, not caring where she plunged the knife, thrusting so deeply that the point scraped against the glass, leaving long thin scratches on the pane. She eventually stopped, the energy just draining from her, but once it was over she hadn’t felt contrite or ashamed. She bundled up the material, composed an excuse for her husband and ordered some new curtains from a magazine she subscribed to. Why she felt like this she did not know. It seemed to her she had always been this way: always bitter and resentful because she did not count, and even now she did not know how to change this.

As she climbed the mound to the house, which was already strewn with lights, she began to prepare herself for the night ahead. She knew it annoyed her husband that she couldn’t interact with their neighbors. He had known about the comments and gossip that started after their engagement had been announced, but only from a distance. To his face, at least, it was clear that all the men were secretly envious that he had managed to entrance a pretty nineteen-year-old. He did not know that the women had labeled his wife a harlot and a temptress; that despite the respectability of his name, to them she was still no better than his whore. Nor did he ever guess at how they stared at her belly after the first six months and noted with pursed lips and inward smiles that it had continued to stay flat. He did not sense their distaste, he only saw her isolation, an isolation he believed was self-imposed. That was why he left her at gatherings. After a few weeks into their marriage, he told her that if he stayed with her, she would never force herself to socialize. He chose not to acknowledge that whether he was with her or not, it made no difference.

So when they reached the door and were shown through to the garden, he immediately detached himself, leaving her standing on the back porch, cradling the flowers she had brought and staring at the islands of people knotted among the expanse of green punctured by white-clothed tables and multicolored streamers of silver, turquoise and gold.

She moved through these islands like a navigator through treacherous waters, slipping between the gaps she could find until she reached a small clearing that had not yet been invaded. She did not even try to see where her husband had gone. She came near one of the long tables covered with steaming hams and bowls of salad and rested the flowers near the paper cups and the punch bowl. Nearby stood a group of huddled men, whom she ignored. Instead she served herself a drink, and as she picked over the food she began to wonder how she would be able to get through the evening without taking a knife to something.

“Must just eat you up, Leo,” one of the men near her said.

“He’ll be gone soon, we all know he won’t stay.”

“What was he doing up in Oregon anyway?”

“Salesman.”

“Walter knows he ain’t no farmer. Blood or no blood he’s seen you sweat over this place and he won’t do anything that ain’t in the interests of the farm. Ain’t no salesman can farm.”

“Yeah, but he did use to farm here, didn’t he?”

“That was a long time ago, though.”

“To be sure.”

“You’re the one who’s been here. No one cares about that firstborn stuff. It’s about what you done, not what position you were born into.”

“I hope he knows that.”

“He’s a shrewd man, your pa.”

“Yeah and a sick one. Sick ones stop being shrewd and start getting sentimental.”

“Not when it comes to money they don’t.”

“And besides, if your pa does start to feel sentimental all’s he got to do is start remembering why he sent him away in the first place.”

“Come on now, Dan, everyone knows that were an accident.”

“I don’t want to talk about that.”

“No … sure, Leo, of course. We meant no disrespect.”

“Why, Anne-Marie, don’t you look fetching?”

Anne-Marie turned to see her cousin, the girl she had grown up with, standing before her, a broad smile drawing a hole in her wide, pink flushed face.

“Thank you, Louise,” she replied calmly, though she turned away briefly and slowly closed and reopened her eyes. She had not spoken with her cousin in weeks but each time she did it drained her. It ate up all her reserves to keep a neutral expression on both her tongue and her face, when secretly she wished God would just grant her lifelong wish and snap the girl’s neck like a twig.

“So thin, though, Anne-Marie, if people were to look at you they’d think we were still in the Depression. You know I think you’ve lost weight again. You been losing it steadily ever since you left home, but I guess that’s what happens when you have to cook for yourself. I noticed Lou is thinner than he was, too. Maybe you should talk him into hiring you a housekeeper, if he can afford it on a local doctor’s wage.”

“I wouldn’t know. I don’t question him about his finances.” Anne-Marie turned to her plate. Louise cackled in laughter and put a hand on her shoulder.

“My God, what wife doesn’t know how much she can push her husband for? You are a funny one. The very least he can do is get you some Negro girl in the place, preferably one from down south somewhere. They don’t haggle as much as the ones up here. I insist you try, any more weight loss and people will start thinking something’s wrong with you.”

“I’m just fine,” snapped Anne-Marie as her jaw ached under the strain.

“But maybe not,” said Louise, cocking her head to her side and fingering the hem of Anne-Marie’s dress. “Maybe the dress just makes it seem that way. Boy, you can do anything with a sewing machine,” she said, dropping her hand away and smoothing down the cream silk that fell across her own waist and flared out at her hips. Suddenly she laughed. “Remember all those times I’d come home and find you just sewing away, always mending, always poring over your clothes and stuff. Why you didn’t just ask Daddy to buy you something new I could never understand.”

Anne-Marie stared at her cousin. She saw her cock her head to her side and gaze at her as if she were waiting for something, always waiting for something, and then finally smiling as she used to when she saw that Anne-Marie could not think of a way to respond.

“Daddy said you used to get that from your mother, that thriftiness.” She bent nearer to her at this point. “Truth be told, I think he was glad that’s all you got.”

Anne-Marie cleared her throat and tried to turn away. Louise stepped back and frowned.

“Sorry, I forgot how you never mention your mother.”

And she never did—never. I remember my father saying how he had asked about her once. My grandmother had gotten up from her chair and left the room without saying a word, and when he had asked his father why she was that way, all my grandfather could say was, “Some things just run through you so deep, all they leave is a hole.”

And so it was with my grandmother, so that she became little more than a void in the disguise of a woman.

But while Anne-Marie may have refused to talk about her mother, almost everybody else did. They couldn’t help themselves after her uncle’s wife, a rotund woman who had an unfortunate partiality to loudly colored prints, had taken every opportunity at the store or in the street, to explain to her neighbors how her sister-in-law had turned up on their doorstep with a carpet bag, a spaniel puppy and a seven-year-old girl in a blue gingham pinafore.

Soon everyone would come to know that Eleanor Brown had left her husband, a teacher in San Diego, to come back to her home town. The rumor was that he had run up debts and their house was to be sold, though people suspected there were far more shameful indiscretions than these two meager facts. No one said so directly, but everyone knew they would divorce. People, including her own family, had assumed that Eleanor would stay in town under the supervision and support of her brother and create a new life, but it was not to be. In the early hours of a Wednesday morning, three weeks after she arrived, her brother came down to his morning coffee to find that not only had it not been made, but his wife also sat at their table, her head in her hands with a note laid open before her. While brief, Eleanor was certainly direct. The child was to stay with them until she could find a job and a home elsewhere. She left no forwarding address in case they chose to forward her daughter to her as well as her mail. So they were left with this little girl from San Diego whom they had only ever met once before and who was now to be staying with them for heaven knew how long.

At first Eleanor decided to keep up the pretense of parenthood and send them money every month. The amount always varied. Then after two years she sent forty dollars and a wedding photograph of her and her new husband. Her sister-in-law had humphed at this.

“At least she’s not wearing white,” she had said.

That was the last they had ever heard of her.

It was after this that they changed my grandmother’s name. Her aunt had never liked it. She had thought it pretentious, flighty: in short, far too reminiscent of the traits inherent in her wayward mother. So they had taken it away and instead settled her with her middle name Anne, though they thought Anne Brown was far too dour so they had given her Marie as well. They had thought in doing so they were being kind.

So she had lived and grown up with them as Anne-Marie Brown, one of them, but always aware this was by their admission rather than her right, so that at any moment this could be taken away and no one would intervene. How much of this was of her own thinking and how much was gauged by their implication, no one will ever really know. What is known is that one day at the age of nineteen, Anne-Marie had placed the silver tray of honey roast chicken on the protective place mat in front of her uncle and when he stood up and scraped the carving knives against each other, over the clang of metal she announced there and then that she didn’t want to be served any dark meat and that she was planning on marrying Dr. Lou Parks.

Her aunt had dropped her fork, her uncle had put down his carving knife and her cousin had shrieked with laughter.

“You can’t marry Lou Parks,” Louise squealed. “He’s a hundred years old.”

“Forty-nine,” Anne-Marie had replied quietly.

Over the dimming candles and intermittent incredulous gasps and other noises, they had questioned her for over an hour, while the chicken shriveled up and the steamed vegetables began to wilt, until all they were left with was a cold meal and more questions than answers.

How had this happened? they wanted to know. Had she done anything improper? Louise at one point demanded to know if she had slept with him, at which point out of disgust or fright her mother had slapped her across the mouth and Louise had burst out crying, which had only made her mother start bawling herself. Her uncle sat there trying to compose himself, but he was hungry and he stared plaintively at the chicken and mourned the fact that on any other evening, he would by now be sitting in his study, fed and sated, not stiff-backed at the dinner table with his women crying.

“Don’t you want to marry someone your own age?” her aunt asked her. “If you ever had any children, by the time they are grown up, why—” she turned to her husband, her hands splayed in a posture of both pleading and exasperation “—he’ll be old enough to be their grandfather.”

“I don’t know if you’ve noticed but there aren’t any young men left anymore,” Anne-Marie answered coolly. “And the last thing I want is to raise some brat on my own while my husband gets his head blown off overseas.”

Her aunt had opened and closed her mouth like a fish choking on air.

Finally, in an effort to impart some good on the proceedings, her uncle had asked Anne-Marie if she truly loved this man; if she was ready to spend the rest of her life with him, until death do they part, and, more importantly, if she really knew what this meant. She had leaned back in her chair and sighed, then looked at him with such tired contempt that when she dropped her head and turned away he had not dared to press her for an answer. For the very first time he had seen her naked in expression and suddenly he had an overwhelming desire to get the girl out of his house once and for all.

In that fact, he could not have known how alike in sentiment they were, probably the only thing, apart from blood, that they ever had in common.

Her family could not understand why Lou Parks wanted to marry her. A bachelor, with a taste for whiskey and a strong Presbyterian streak, he seemed the least likely person to fall for Anne-Marie. Her uncle couldn’t help but question him over the validity of the relationship, when Lou, like a lovesick teenager, had come to his house the next day to properly ask for Anne-Marie’s hand. Anne-Marie had bent over the upstairs banister, watching her cousin and aunt in the corridor below, trying to listen in on what he was saying, and she had smiled to herself at what she had accomplished, and even more that they would never know how she did it.

No one believed it would actually happen. They all thought it was a brief bit of madness that would be slowly weaned out before it could ever come to full destructive fruition. But even though the night before the wedding they had lain in their beds and wondered aloud if he would go through with it, the next day Lou had stood up in the church and never once faltered in his vows. Even their kiss had seemed sincere, as he cupped Anne-Marie’s waist to draw her closer. Louise had made a gagging noise until she was hit on the arm to make her stop.

Her family was afraid of her after that, and she was glad. She saw how they greeted her and how anytime they said the words Mrs. Parks, their tongues seemed to slide over the letters as if, should they linger too long, someone would laugh at them and they would realize that they were the punch line to a joke she had been playing on them all this time. That wasn’t too far from the truth and part of them suspected so. To them she was a stranger, capable of what … they did not know, nor did they care to find out. But Anne-Marie did, and she was waiting: waiting for the chance for her true self to emerge as an independent, not defined by who she was with or whose house she lived in. But the more she waited, the less likely it seemed that it might happen.

She saw her cousin look longingly over her shoulder and in that instant she took the chance to slip away. By the time Louise had noticed her absence, Anne-Marie had moved too far away for her to want to call her back. She wove her way through the garden. They called it a garden but in her mind it was no better than an untilled field, just long grass and bushes that sprawled down the back of the house in a wide arc and before she knew it, she had let it lead her away as it branched off to the left behind some trees. It was there, sitting on a bench, that she found Cal Hathaway. Later on in life he would say she was looking for him but she did not know it; that it was fate that had led her there. I am inclined to agree.

“I’m sorry, I did not mean to intrude,” she said. He looked up at her then. He was reclining back on the white bench, a tumbler beside him and a bottle of scotch.

“Who are you? I ain’t seen you before,” he said curiously.

“I’m Anne-Marie Parks,” she replied coolly and then held out her hand as an afterthought, but he’d already turned from her back to his scotch and her hand fell limply to her side.

“You from here?” he asked sharply.

“Most of my life.”

“How come I don’t know much of you then?”

“I don’t know. Nobody knows much of me.”

He looked her up and down. “Probably the best way,” he said conclusively. “Soon as anyone knows anything about you in this place they all start wanting a piece. Well, they’ve had as much as they’re going to get of me.”

“Where you been? They—I heard that you had been away for some time now.”

“Oregon. I’m a salesman there.”

“Oh?” enquired Anne-Marie casually. “What do you sell?”

He shrugged. “Whatever needs selling.”

This was how my grandfather was—cold, casual, unattached to anything and anyone except his daughter. He’d had enough of attachments at this stage in his life. All they ever seemed to do was bring him harm.

“I heard your daddy is dying.”

“You heard right.”

“I’m sorry.”

“You wouldn’t be if you knew him.”

“I think you knew him and you’re still sorry, or you wouldn’t be down here away from everyone knocking back scotch.”

In the dark she could see his gaze arrest in surprise. His hand hovered over the bottle before he poured a thimbleful.

“Want to taste?”

She drew herself up.

“Ah, now there’s no need to be like that. A bit won’t kill you and it’s the good kind anyhow. My pa has good taste in liquor.”

“How old are you?” she asked.

“I’m thirty-five.”

“Well, it’s a sorry state when a man of your age is hiding from a party thrown for him at the bottom of a garden, drinking stolen liquor.”

Cal laughed. “You ain’t very popular, are you?”

Anne-Marie put a hand to her neck and then dropped it in irritation.

“About the same as you from the sounds coming out of people. Who says I ain’t anyhow?”

In the dark he seemed to smile. “Nobody is who likes pointing out other people’s truths.”

He stood up then and she saw how tall he was, the broad shoulders, the thin nose and square jaw, his long hands that were now cradling his drink. She would come to know how much he would like to drink and for a long time it would not bother her.

“What did you say your name was?”

“Weren’t you paying attention? I told you it was Anne-Marie.”

He shrugged. “Anne-Marie just don’t seem to suit, is all. You don’t look like an Anne-Marie to me.” He licked his lips. “Anne-Maries are soft creatures. You ain’t soft, you’re hard and brittle and harder because you know you’re brittle. Your name is a lie, Anne-Marie, but then so is mine. People call me Cal, have done all my life, but my name is Abraham. You know your bible—Abraham is the father of the twelve nations of God’s chosen people, all-wise, all-knowing. But I ain’t no Abraham just like you ain’t no Anne-Marie, so what then is your name, girl?”

It was then, my grandmother said, that she knew it. She watched the swaying man try to steady himself on his drunken feet and even though he wasn’t handsome, even though he was just some salesman from Oregon, even though she felt a creeping vine of disdain tug at the corners of her mouth as she observed him, it could not change her revelation.

“One day you will know,” she would say much later. “You will just know and all you can do is pray for the serenity to accept it and the courage to follow through.”